Abstract

PHD1–3 (prolyl hydroxylases 1–3) catalyse the hydroxylation of HIF (hypoxia-inducible factor)-α subunit that triggers the substrate ubiquitination and subsequent degradation. The RING (really interesting new gene) finger E3 ligase Siah2 preferentially targets PHD3 for degradation. Here, we identify the requirements for such selective targeting. Firstly, PHD3 lacks an N-terminal extension found in PHD1 and PHD2; deletion of this domain from PHD1 and PHD2 renders them susceptible to degradation by Siah2. Secondly, PHD3 can homo- and hetero-multimerize with other PHDs. Consequently, PHD3 is found in high-molecular-mass fractions that were enriched in hypoxia. Interestingly, within the lower-molecular-mass complex, PHD3 exhibits higher specific activity towards hydroxylation of HIF-1α and co-localizes with Siah2, suggesting that Siah2 limits the availability of the more active form of PHD3. These findings provide new insight into the mechanism underlying the regulation of PHD3 availability and activity in hypoxia by the E3 ligase Siah2.

Keywords: complex formation, hypoxia, prolyl hydroxylase domain containing 3 (PHD3), protein degradation, Siah2, ubiquitination

Abbreviations: Ab, antibody; DMEM, Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium; DTT, dithiothreitol; GST, glutathione S-transferase; HEK-293, human embryonic kidney 293; HEK-293T cells, HEK-293 cells expressing the large T-antigen of (simian virus 40); HIF, hypoxia-inducible factor; Mdm2, murine double minute 2; ODD, oxygen-dependent degradation; PHD, prolyl hydroxylase domain containing; pVHL, von-Hippel–Lindau protein; RING, really interesting new gene

INTRODUCTION

Regulation of cellular responses to environmental cues relies on post-translational modification of proteins that determine their subcellular localization, activity and stability. Ubiquitination is one such modification, and requires the co-ordinated action of enzymes involved in activation (E1), assembly (E2) and conjugation of ubiquitin on their target substrates, either as a single molecule or as polymeric linear or branched chains [1]. Specificity of protein ubiquitination is determined primarily by the E3 ligase, which specifically recognizes the appropriately modified substrate. Major classes of E3 ligases include those that function as single subunits, including HECT (homologous to E6-associated protein C-terminus) (e.g. E6AP, Itch and WWP1) and RING (really interesting new gene) finger proteins [Mdm2 (murine double minute 2), BRCA1 (breast-cancer susceptibility gene 1) and Cbl], as well as multi-subunit complexes [e.g. SCF (Skp1/cullin/F-box) and APC (anaphase promoting complex)] [2].

Siah was originally identified in Drosophila (Sina) as a potent RING finger E3 ligase that plays an important role in Drosophila eye development by targeting the receptor Tramtrack for degradation [3,4]. Siah1 and Siah2 are the mammalian homologues that have been implicated in the regulation of proteins including NCoR (nuclear receptor co-repressor), BAG-1 (Bcl2-associated athanogene), Kid, TRAF-2 (tumour-necrosis-factor-receptor-associated factor 2) and β-catenin [5–9]. Whereas Siah1 and Siah2 proteins share 80% sequence similarity, mechanisms whereby these enzymes recognize and modify their substrates remain elusive. We have demonstrated previously [10] that Siah2 mediates the ubiquitin-dependent degradation of PHDs (prolyl hydroxylases), thereby identifying a hitherto unknown layer in the regulation of the cellular hypoxic response.

Through their hydroxylation of HIF (hypoxia-inducible factor)-1α at conserved proline residues (Pro402 and Pro564), the PHDs play a key role in the regulation of HIF-1α expression in normoxia [11]. Such a hydroxylation is prerequisite for association of the E3 ligase component pVHL (von Hippel–Lindau protein) with HIF-1α, which results in its ubiquitination-dependent degradation [12,13]. Reduction of oxygen concentration attenuates the activity of PHDs, thereby decreasing the association of HIF-1α with pVHL, which leads, in turn, to the stabilization of HIF-1α. The stabilized HIF-1α subunit heterodimerizes with HIF-1β to induce transcription of more than 50 genes implicated in cellular metabolism, growth, death, as well as in almost any other cellular function [14]. In anoxia or severe hypoxia (0–1% oxygen), PHDs, which require oxygen molecules for their enzymatic activity, are inactive, but in milder hypoxia (2–5% oxygen) they retain their enzymatic activity, although HIF-1α is already stabilized. This phenomenon is partly explained by the finding that certain PHDs (PHD3 and to a lesser extent PHD1) are substrates for the RING finger E3 ligases Siah1/2, which targets them for ubiquitination-dependent degradation in mild hypoxia [10].

Although PHD1, PHD2 and PHD3 can hydroxylate HIF-1α in vitro [15], the three isoforms exhibit different patterns of expression among tissues [16,17]. At present, PHD2 and PHD3 appear to be the predominant forms that contribute to HIF-1α hydroxylation in cells [18]. Whereas PHD2 was suggested as the primary enzyme that affects HIF-1α hydroxylation in normoxia [19], PHD3 appears to retain its activity in mediating such a modification in hypoxic conditions [10].

While targeting the ubiquitination and degradation of PHD3 and PHD1, Siah2 also associates with PHD2. This observation raised the possibility that events, in addition to the interaction with Siah2, play determinant roles in the ubiquitination and degradation of PHD3 and PHD1 by this RING finger protein. Here, we demonstrate that N-terminal domains of PHD1 and PHD2 limit their direct interaction with Siah2 and that PHD3 can form complexes that include homo- and hetero-dimers/multimers, and that assembly of PHD3 into complexes affects its activity towards HIF-1α and susceptibility for degradation by Siah2. These findings extend our understanding of the mechanism underlying the regulation of PHD3 availability and activity by the E3 ligase Siah2.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cell culture and media

HEK-293T cells [human embryonic kidney 293 cells expressing the large T-antigen of SV40 (simian virus 40)] were cultured in DMEM (Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium) with 10% calf serum and antibiotics. HeLa cells and A498 cells were cultured in DMEM with 10% (v/v) foetal bovine serum and antibiotics.

Abs (antibodies), plasmids and chemical reagents

Anti-FLAG tag (monoclonal and polyclonal M2) and anti-β-actin Abs were purchased from Sigma. Anti-HIF-1α Ab (Novus) was used for Western blotting. Rabbit polyclonal anti-PHD1, PHD2 and PHD3 Abs (BL525, BL521 and BL526 respectively) were purchased from Bethyl Laboratories and mouse monoclonal PHD3 Ab was kindly provided by Dr Peter Ratcliffe. Anti-Siah2 (N-14) Ab was obtained from Santa Cruz Biotechnology. Anti-Myc-tagged Ab (9E10) and anti-HA-tagged Abs (12CA5) were purified from a hybridoma clone. Hydroxylation-specific HIF-1α Ab [anti-(HIF-1α hydroxylated Pro564) Ab] was generated using an HIF-1α Pro564-hydroxylated peptide for immunization. pcDNA3-FLAG–PHD1, –PHD2 and –PHD3 were described previously [10]. pcDNA3-Myc–PHD1, –PHD2 and –PHD3 were generated by subcloning corresponding sequences from FLAG-tag vectors into pcDNA3-Myc vectors. ΔPHD1 and ΔPHD2 were generated by PCR using FLAG–PHD1 or FLAG–PHD2 as templates. Lactacystin was purchased from Boston Biochemicals.

Immunoprecipitation and Western blotting

HEK-293T cells (4×105) were transfected using the calcium phosphate method. HeLa cells (1×105) were transfected using Lipofectamine™ (Invitrogen). Transfected cells were lysed in lysis buffer [50 mM Tris/HCl, pH 8.0, 150 mM NaCl, 1 mM EDTA, pH 8.0, 1% (v/v) Triton X-100, 0.1 μg/ml PMSF and 2 μg/ml leupeptin]. Anti-FLAG or anti-Myc Ab (1 μg) was added to 1 mg of total lysate, followed by Protein G–agarose (Invitrogen) incubation. The immunoprecipitates were washed four times with lysis buffer, then subjected to SDS/PAGE (immunoprecipitates or 40 μg of total lysate/lane) and transferred on to a nitrocellulose membrane (Osmonics). The membrane was probed with primary Abs, followed by a secondary Ab conjugated with Alexa Fluor® 680 or 800, and detected by the Odyssey Fluor imaging system (Licor).

Hypoxia treatment

Cells were subjected to hypoxia in a hypoxia workstation (Biotrace) maintained at 1% oxygen (rest balanced with 5% CO2 and nitrogen). Cells were harvested with PBS and lysis buffer pre-equilibrated in the workstation overnight. Incubation for immunoprecipitation was performed in a secured screw-cap tube at 4 °C. The following washes were carried out in the workstation with pre-equilibrated cold washing buffer.

Gel filtration

Control or FLAG–PHD3 plasmid (3 μg) was transfected into HEK-293T cells (4×105) with Lipofectamine™ plus. After 48 h of transfection, cells were subjected to hypoxia (1% oxygen) for 4 h. HeLa cells were subjected to hypoxia (1% oxygen) for 7 h and A498 cells for 6 h. Cells were harvested with PBS and lysed in lysis buffer (1 ml) in the hypoxia workstation. Cell lysates (200 μl of a 2.5 μg/μl solution) were subjected to gel filtration through a Superose 6 10/300 GL column (GE Healthcare) at a flow rate of 0.35 ml/min with a buffer containing 25 mM Tris/HCl (pH 7.5), 1 mM EDTA, 0.01% Nonidet P40, 10% (v/v) glycerol, 1 mM DTT (dithiothreitol), 0.15 M NaCl, 0.2 μg/ml leupeptin, 0.2 μg/ml antipain and 1 mM PMSF. For the analysis of endogenous PHD3, half of the volume (200 μl) of the fractions obtained from gel filtration was concentrated by trichloroacetic acid precipitation prior to SDS/PAGE. Intensity of the bands was calculated using the Odyssey imaging software. The values were normalized against the fraction that exhibited the lowest intensity in each experiment (set to value of 1).

In vitro hydroxylation assay

Bacterially purified GST (glutathione S-transferase)–HIF-1α ODD (oxygen-dependent degradation) domain (amino acids 531–603 of human HIF-1α) was incubated with in vitro translated PHD3 or PHD3 contained in the fractions from the gel filtration in hydroxylation buffer (20 mM Hepes, pH 7.4, 5 mM KCl, 1.5 mM MgCl2, 260 μM FeCl2, 5 mM 2-oxoglutarate, 0.6 mM ascorbic acid, 1 mM 2-mercaptoethanol, 1 mM DTT and 1 mM PMSF) at 30 °C for 1 h [20]. Hydroxylation was detected by anti-(HIF-1α hydroxylated Pro564) Ab.

RESULTS

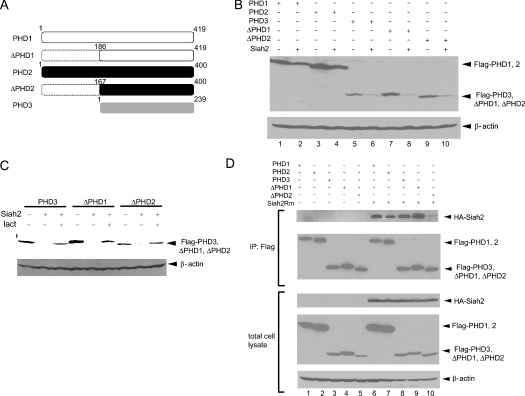

N-terminal deletion mutants of PHD1 and PHD2 are efficiently degraded by Siah2

Although Siah2 associates with PHD1–3, albeit at different efficiencies, it does not affect the stability of PHD2, and it is less efficient at degrading PHD1 than PHD3. To understand the nature of these differences, we searched for possible variations in the sequences of the three PHDs. Alignment of the amino acid sequences of the three PHDs revealed that, while their C-terminal portions are well conserved, both PHD1 and PHD2 contain an N-terminal extension that is not present in PHD3. To test the possibility that this N-terminal domain determines the ability of Siah2 to affect PHD stability, we deleted the N-terminal portion of both PHD1 and PHD2 (Figure 1A). Co-expression of the ΔPHD1 and ΔPHD2 forms with Siah2 revealed that both were efficiently degraded by Siah2 (Figure 1B, lanes 7–10). Degradation of PHD3, ΔPHD1 and ΔPHD2 mediated by Siah2 could be attenuated by addition of the proteasome inhibitor lactacystin (Figure 1C). These observations suggest that the extended N-terminal regions of PHD1 and PHD2 confer resistance to degradation by the RING finger E3 ligase Siah2.

Figure 1. Efficient degradation of ΔPHDs by Siah2.

(A) Schematic diagram of three mouse PHDs and their deletion mutants. Positions of the deletions are indicated by amino acid number. (B) Siah2-dependent degradation of ΔPHDs. FLAG–PHD and Siah2 plasmid (2 μg each) were co-transfected into HEK-293T cells. Total cell lysates were subjected to SDS/PAGE, and the membrane was probed with anti-FLAG Ab (top panel) and anti-β-actin Ab (bottom panel) as an internal control. (C) Inhibition of Siah2-dependent ΔPHDs degradation by lactacystin (lact). FLAG–PHDs and Siah2 plasmid (2 μg each) were co-transfected into HEK-293T cells. Cells were treated with lactacystin (10 μM for 5 h) and harvested. Total cell lysates were subjected to SDS/PAGE, and the membrane was probed with anti-FLAG Ab (top panel) and anti-β-actin Ab (bottom panel). (D) Interaction of ΔPHDs with Siah2. The RING-mutant form of HA–Siah2 (Siah2Rm) was co-transfected with FLAG-tagged PHD plasmids in HEK-293T cells and cell lysates were subjected to immunoprecipitation (IP) with anti-FLAG Ab. Western blotting with anti-HA Ab shows the interaction of Siah2Rm with PHDs. Immunoprecipitated PHDs (second panel from top) and expression of HA–Siah2Rm and FLAG–PHDs as well as β-actin control in total cell lysate are shown in the three lower panels.

Next, co-immunoprecipitation was used to test the interaction between the ΔPHD1/2 forms and the RING-mutant form of Siah2. Siah2 interaction with ΔPHD1 was stronger compared with the full-length PHD1 (Figure 1D, compare lane 6 with lane 9). In contrast, deletion of the PHD2 N-terminus significantly reduced the degree of interaction with Siah2 (Figure 1D, compare lane 7 with lane 10). These results suggest that although the N-terminal domains for PHD1 or PHD2 are important in determining availability for degradation by Siah2, other factors in addition to the interaction contribute to the ability of Siah2 to target their degradation.

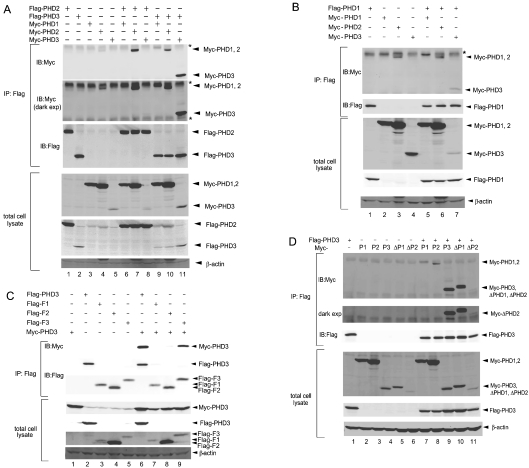

PHD is found as monomer and as part of higher order complexes

The observation that Siah2 can mediate degradation of ΔPHD2 (Figures 1B and 1C), despite its mild interaction (Figure 1D), points to the possibility of its regulation in trans, e.g. trans-ubiquitination, which was shown for other RING finger E3 ligases, including Mdm2 [21,22]. Trans-ubiquitination would require the formation of complexes between PHDs, such as PHD3 and ΔPHD2. The possibility that PHDs may be part of higher order complexes was also suggested in earlier studies [23] and was further evidenced by the notion that members of the related family, collagen hydroxylases, are able to form such complexes [24]. To test this possibility, co-immunoprecipitation of exogenously expressed FLAG–PHD2/3 with Myc–PHD1–3 was performed. The results revealed the existence of PHD2–PHD2 and PHD3–PHD3 homodimers (Figure 2A, lanes 7 and 11). Intriguingly, PHD3 also formed heterodimers with PHD1 and PHD2 (Figure 2A, lanes 8–10). A similar experiment performed with PHD1 confirmed the formation of PHD1–PHD1 homo- as well as PHD1–PHD3 hetero-dimers (Figure 2B, lanes 5 and 7). Reciprocal co-immunoprecipitation experiment using anti-Myc Ab for immunoprecipitation revealed a similar interaction profile, further supporting the interactions among PHDs (results not shown). These results support the existence of homo- and hetero-dimers and possibly multimers that may assemble into higher order complexes (see below) among PHD family members. Interaction among the endogenous PHDs could not be achieved due to the limited efficiency of the Abs currently available for immunoprecipitation, combined with the low expression level of the endogenous proteins.

Figure 2. Homo- and hetero-multimerization among the PHDs.

(A) Homo-/hetero-multimerization of PHD2 and PHD3 with PHDs. HEK-293T cells were transfected with FLAG–PHD2 or FLAG–PHD3 together with Myc–PHD1, Myc–PHD2 or Myc–PHD3. Cell lysates immunoprecipitated with anti-FLAG Ab were subjected to Western blotting probing with anti-Myc Ab (second panel: dark exposure), anti-FLAG Ab or β-actin. Asterisk indicates the heavy/light chains of anti-FLAG Ab. (B) Homo-/hetero-multimerization of PHD1 with PHDs. HEK-293T cells were transfected with FLAG–PHD1 together with Myc–PHD1, Myc–PHD2 or Myc–PHD3. Cell lysates immunoprecipitated with anti-FLAG Ab were subjected to Western blotting probing with anti-Myc Ab, anti-FLAG Ab or β-actin. Asterisk indicates the heavy chain of anti-FLAG Ab. (C) C-terminal portion of PHD3 is required for homomultimerization. HEK-293T cells were transfected with Myc–PHD3 together with PHD3 fragment plasmids (FLAG–F1, FLAG–F2 or FLAG–F3). Cell lysates immunoprecipitated with anti-FLAG Ab were subjected to Western blotting probing with anti-Myc Ab, anti-FLAG Ab or β-actin. (D) Hetero-multimerization of ΔPHDs with PHD3. Myc–ΔPHDs or Myc–PHD1, Myc–PHD2, Myc–PHD3 and FLAG–PHD3 were co-transfected into HEK-293T cells. Cell lysates were subjected to immunoprecipitation with anti-FLAG Ab and the blot was probed with anti-Myc Ab (second panel: dark exposure), anti-FLAG Ab or β-actin. IB, immunoblot; IP, immunoprecipitation.

To determine the interaction domain required for PHD3 homo- or hetero-multimerization, deletion mutants of PHD3 were utilized in a similar co-immunoprecipitation experiment (see Figure 4A). Of the three fragments (F1–F3), only F3 interacted with full-length PHD3, although the degree of interaction was weaker than seen between full-length proteins, suggesting a possible role of F1 and F2 or conformation of the full-length protein in this interaction (Figure 2C, compare lane 6 with lane 9). In agreement with this possibility, the larger fragment of F1–F2, which lacks F3, was also able to interact with PHD3 to the extent seen with F3 (results not shown).

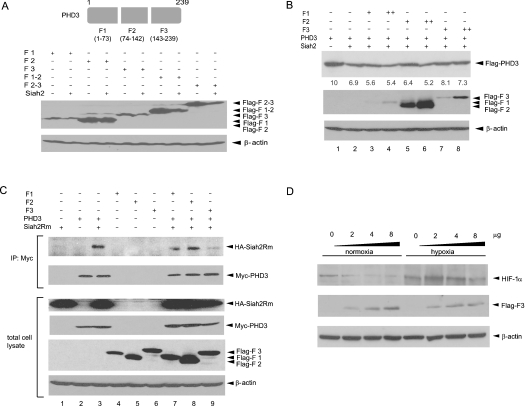

Figure 4. Degradation of PHD3 by Siah2 is dependent on its C-terminal region.

(A) Degradation of PHD3 deletion mutants by Siah2. Schematic diagrams of PHD3 deletion mutants are shown in the upper panel. Amino acid numbers are indicated for each fragment. Siah2 and PHD3 fragment plasmids were co-transfected into HEK-293T cells. The total cell lysate was subjected to SDS/PAGE and the membrane was probed with anti-FLAG Ab (top panel) and anti-β-actin Ab (bottom panel). (B) Competition of PHD3 and its deleted form for Siah. FLAG–PHD3 (2 μg) together with each of the FLAG–PHD3 fragments (0.5 and 2 μg) were co-transfected with Siah2 (2 μg) into HEK-293T cells. The total cell lysate was subjected to Western blotting and the membrane was probed with anti-FLAG Ab (top and middle panels) and anti-β-actin Ab (bottom panel). The numbers below the top panel indicate the relative expression levels of PHD3. (C) Effect of PHD3 fragments on PHD3–Siah2 interaction. The RING-mutant form of HA–Siah2 (Siah2Rm) was co-transfected with Myc-PHD3 plasmid together with FLAG–PHD3 fragments in HEK-293T cells, and the cell lysate was subjected to immunoprecipitation (IP) with anti-Myc Ab. Western blotting with anti-HA Ab shows the interaction of Siah2Rm with PHD3. Immunoprecipitated Myc–PHD3 (second from top panel), expression of HA–Siah2Rm, FLAG-tagged PHD3 fragments and β-actin control in cell lysate are shown in the lower panels. (D) Exogenous expression of F3 alters HIF-1α expression. Different amounts of PHD3-F3 (indicated on the top of the panel) were transfected into HeLa cells, and 48 h later, the cells were exposed to hypoxia (1%) for 5 h and the cell lysate was subjected to Western blotting. Expression of HIF-1α (top panel), F3 (middle panel) and β-actin (bottom panel) is shown.

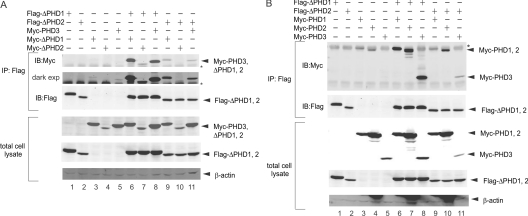

As both ΔPHD1 and ΔPHD2 are efficiently degraded by Siah2 (Figure 1B), we next tested whether these fragments could also be included in heteromultimers, which could explain Siah2-dependent degradation in trans. Heteromultimers of ΔPHD1 or ΔPHD2 and PHD3 were observed (Figure 2D), indicating that hetero-multimers formed among PHDs could affect their susceptibility to Siah2-mediated degradation.

Furthermore, we assessed the possible formation of complexes between ΔPHD and full-length PHDs. A series of co-immunoprecipitations led to the identification of ΔPHD1 and ΔPHD2 homomultimers (Figure 3A, lanes 6 and 10) and heteromultimers between ΔPHD1 and ΔPHD2 (Figure 3A, lanes 7 and 9), as well as between ΔPHD2 and full-length PHD3 (Figure 3A, lane 11).

Figure 3. ΔPHDs homo- and hetero-multimerize with PHDs.

(A) Homo-/hetero-multimerization of ΔPHDs. FLAG–ΔPHD1 or FLAG–ΔPHD2 and Myc–PHD3, Myc–ΔPHD1 or Myc–ΔPHD2 were co-transfected into HEK-293T cells. Cell lysates were subjected to immunoprecipitation with anti-FLAG Ab and the blot was probed with anti-Myc Ab (second panel: dark exposure), anti-FLAG Ab or β-actin. Asterisk indicates the light chain of anti-FLAG Ab. (B) Heteromultimerization of ΔPHDs with PHD1, PHD2 and PHD3. FLAG–ΔPHD1 or FLAG–ΔPHD2 and Myc–PHD1, Myc–PHD2 or Myc–PHD3 were co-transfected into HEK-293T cells. Cell lysates were subjected to immunoprecipitation with anti-FLAG Ab, and the blot was probed with anti-Myc Ab, anti-FLAG Ab or β-actin. Asterisk indicates the heavy chain of anti-FLAG Ab. IB, immunoblot; IP, immuno precipitation.

Another set of co-immunoprecipitation experiments utilizing ΔPHD1/ΔPHD2 and the full-length PHD1–3 was performed. ΔPHD1 interacted with all three PHDs at a similar efficiency (Figure 3B, lanes 6–8), whereas ΔPHD2 primarily formed multimers with PHD2 (Figure 3B, lane 10), but also interacted with PHD3 (Figure 3B, lane 11). This interaction of PHD3 with ΔPHD1 and ΔPHD2 is expected to result in the formation of higher order complexes.

The C-terminal portion of PHD3 is important in Siah2-dependent degradation and competes with full-length PHD3 for Siah2

To identify the domain of PHD3 required for Siah2-mediated degradation, we generated a series of deletion mutants of PHD3 that encompass the N-terminal, central domain and C-terminal portions of the protein (fragments; F1, F2, F3, F1–2 and F2–3, Figure 4A). It has been predicted previously that the catalytic domain of PHD3 consists of eight β-strands [11]. These deletion mutants were designed to retain each of those β-strands intact with F1, F2 and F3 containing 0, 2 and 6 strands respectively. Consistent with earlier findings that revealed that the C-terminal portion of PHD3 is required for association with Siah2 [10], Siah2 caused a marked decrease in the steady-state levels of F3 and F2–3 (Figure 4A). These findings suggest that amino acids 143–239 are important for Siah2's effect on PHD3 stability. Since the F1–2 fragment was also degraded by Siah2, it is possible that amino acids 1–142 harbour additional binding sites for Siah2 or for adaptor proteins that may mediate Siah2 association. Since these results indicated that the C-terminal portion of PHD3 is relevant to both Siah2-mediated degradation and PHD3 multimerization, we next assessed the effect of ectopically overexpressed PHD3 fragments on PHD3 stability. Overexpression of such fragments is expected to inhibit competitively the Siah2-dependent degradation of PHD3, and hence decrease HIF-1α stability. Indeed, although Siah2 expression reduced the level of PHD3 expression, co-transfection of F3 did attenuate, albeit moderately yet reproducibly, the ability of Siah2 to affect PHD3 stability (Figure 4B, compare lanes 1 and 2 with lanes 7 and 8). In contrast, F1 or F2 had minimal effect on Siah2-mediated PHD3 stability (Figure 4B, lanes 3–6). One of the possible mechanisms underlying F3's ability to attenuate the effect of Siah2 on PHD3 is by interfering in the interaction between Siah2 and PHD3. To test this possibility, we monitored F3's effect on the Siah2–PHD3 interaction. Indeed, F3 expression inhibited the Siah2–PHD3 interaction, indicating that F3 competes with full-length PHD3 for Siah2 binding (Figure 4C, compare lane 3 with lane 9). As total intracellular PHD3 activity is directly related to its expression level, F3 is expected to affect the level of HIF-1α expression. Consistent with the inhibitory effect of F3 on PHD3 degradation, increased expression of F3 caused a moderate, yet notable, dose-dependent decrease in HIF-1α expression in both normoxia and hypoxia (Figure 4D). Interestingly, elevated level of FLAG–F3 did not alter the level of endogenous PHD3, implying that FLAG–F3 affects PHD3 activity rather than stability. The latter is consistent with PHD3 hetero- and homo-multimerization, which alters its activity (see below).

PHD3 forms complexes, which affects its hydroxylase activity

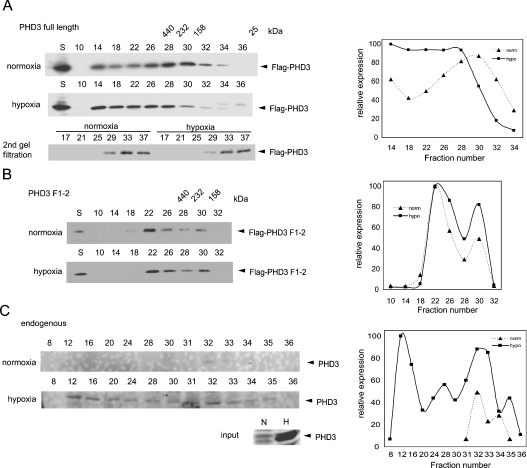

To understand the implications of PHD homo- and hetero-multimerization, we determined the distribution of PHD3 species following separation on a gel filtration column. Size fractionation of PHD3-containing complexes was first performed on lysates prepared from cells transfected with FLAG–PHD3 and maintained in normoxia or hypoxia. Interestingly, PHD3 was found in a wide range of fractions in apparent molecular mass ranging from 30 kDa (monomeric form) up to 2000 kDa (Figure 5A). This observation suggests that PHD3 formed multiple complexes that may possess different biological activities/functions. The pattern of PHD3 distribution was altered in proteins prepared from cells maintained under hypoxic conditions, as reflected by a shift in the distribution of PHD3 towards fractions of higher molecular mass (Figure 5A). This finding suggests that hypoxia may promote formation of large PHD3 complexes. To exclude the possibility that PHD3 may form artificial aggregates during the lysate preparation, we performed a second round of gel filtration using a fraction from low-molecular-mass region. This analysis revealed that PHD3 distributes within the same fraction after the second round of gel filtration, suggesting that the complex is formed due to biological changes that take place in the cells (Figure 5A).

Figure 5. Distribution of PHD3 in a higher-molecular-mass complex.

(A, B) Distribution of PHD3 and PHD3-F1–2. HEK-293T cells transfected with PHD3 were maintained at normoxia or exposed to hypoxia (1%) for 4 h and harvested. Cell lysates were subjected to the gel filtration column separation and separated by SDS/PAGE. Fraction numbers were indicated on top of each panel. Fraction 33 from the first round of gel filtration was used for the second round of gel filtration. The membrane was probed with anti-FLAG Ab. Quantified amount of PHD3 in the fractions is shown in the graph. (C) Distribution of endogenous PHD3. HeLa cells were maintained at normoxia or exposed to hypoxia (1%) for 7 h and harvested. Cell lysates were subjected to the gel filtration as in (A) and (B). Quantified amount of PHD3 in the fractions is shown in the graph.

To determine the role of the putative PHD3 dimerization/multimerization domain, we performed the gel filtration analysis of PHD3-F12 (see also Figure 4A). The results revealed that PHD3-F12 is no longer found within the larger complexes following hypoxia (Figure 5B). This observation suggests that the hypoxia-induced increase in the size of complexes containing PHD3 can be attributed, at least in part, to the dimerization/multimerization of PHD3. Further, the distribution of endogenous PHD3 was monitored in a similar gel filtration assay using HeLa cells, which express higher basal levels of PHDs, which is further induced following exposure to hypoxia in a HIF-1α-dependent manner [11]. Under normoxia condition, PHD3 was found only in fractions 32–34, which represent low-molecular-mass proteins, while under hypoxia condition, endogenous PHD3 was found within the larger-molecular-mass fractions and distributed broadly in a pattern which resembles the exogenous proteins (Figure 5C).

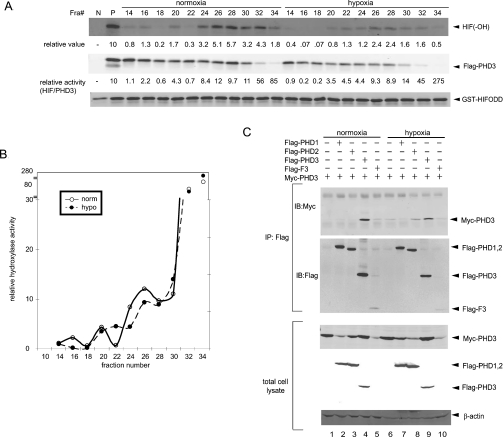

We next determined whether the oligomerization status influenced PHD3s prolyl hydroxylase activity. To this end we set up an in vitro hydroxylation assay using the HIF-1α ODD domain (HIF-ODD) as a substrate. Hydroxylation of HIF-ODD at Pro564 was detected by an affinity-purified Ab that recognizes the hydroxylated ODD-derived peptide. In vitro hydroxylase assay was performed on all the FLAG–PHD3 fractions derived from cells maintained under normoxia or hypoxic conditions (Figure 6A). Whereas the relative expression of PHD3 decreased in the lower-molecular-mass fractions, the degree of its enzymatic activity (hydroxylation of ODD) increased (Figure 6A). The inverse correlation between size and activity suggests that lower-molecular-mass complexes (within the range of 35–250 kDa) exhibit higher specific activity of PHD3 towards the hydroxylation of HIF-1α.

Figure 6. Activities of PHD3 to hydroxylate HIF-1α in different molecular mass complexes.

(A) An in vitro hydroxylation assay using HIF-ODD was performed with the fractions obtained from the gel filtration. After the reaction, samples were separated on gels and the blot was probed with anti-HIF-1α hydroxylated P564 Ab, anti-FLAG Ab and GST Ab. (B) Profile of PHD3 hydroxylase activity in the different complexes. In vitro PHD3 hydroxylase activities are shown by circles and plotted against the y-axis (open: normoxia; filled: hypoxia). The graph represents one of three experiments that were performed independently. (C) PHD2–PHD3 homo-/hetero-multimerization in normoxia and hypoxia. HEK-293T cells were co-transfected with Myc–PHD3 and FLAG–PHD1, FLAG–PHD2, FLAG–PHD3 or FLAG–F3. After 48 h, cells were exposed to normoxia or hypoxia (1%, 5 h) and harvested. Hypoxia-treated cells were harvested in a hypoxia workstation and the following procedures were performed in the workstation. Cell lysates were subjected to immunoprecipitation (IP) at 4 °C with anti-FLAG Ab and immunoprecipitates were subjected to Western blotting probing with anti-Myc Ab, anti-FLAG Ab or β-actin. IB, immunoblot.

The graph in Figure 6(B) reveals the specific activity of PHD3, which was calculated based on the ratio between the degree of HIF-ODD hydroxylation and PHD3 expression level. The peak of PHD3 PHD activity was found in fraction 34, indicating that PHD3 activity is primarily present in the smaller molecular mass fractions (fractions 30–34). Of note, the amount of PHD3 within these fractions decreases in hypoxia.

As samples exposed to hypoxia exhibited increase in the molecular mass of PHD3-containing complexes, compared with normoxia samples, we next examined the composition of PHD molecules under each of these conditions. On the basis of a series of co-immunoprecipitation experiments, PHD3 primarily formed PHD3–PHD3 homomultimers under normoxia, whereas under hypoxia a portion was replaced by heteromultimers of PHD3 with other PHDs, as shown for PHD2 (Figure 6C, compare lanes 3 and 4 with lanes 8 and 9). This result indicates that changes in the relative molecular mass of PHD3 seen in hypoxia may be attributed, in part, to the altered composition of PHD3 complexes, from homo- to hetero-multimers. Hypoxia-induced increase in higher order complexes containing PHD3 and possibly PHD2 correlated with the decrease in the PHD activity of PHD.

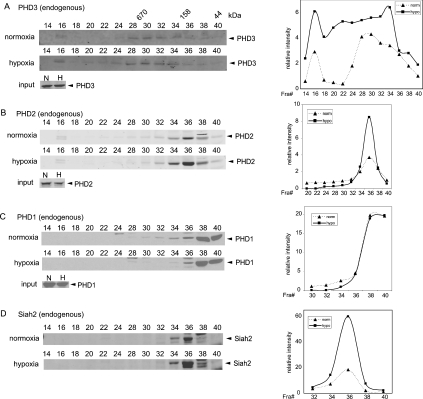

Of importance was to confirm further the changes in the distribution of endogenous PHDs. Using A498 cells that express higher level of PHD3, we have performed a series of gel filtration experiments to follow up the distribution of endogenously expressed PHDs and Siah2. These analyses revealed a broad distribution of PHD3, which is consistent with our finding using exogenously expressed PHD3 and endogenous PHD3 in HeLa cells (Figure 7A). Significantly, a shift of PHD3 towards the highermolecular-mass range was reproducibly seen following hypoxia treatment, which is also consistent with the results in other cell lines, thereby substantiating the finding that PHD3 is assembled into higher order complexes under hypoxia. Importantly, Siah2 and PHD2 were found in smaller complexes (approx. 160 kDa; Figures 7B and 7D), which is within the size range of dimer to tetramer of these proteins, whereas most of PHD1 was found in smaller complexes (50 kDa), reflecting a monomeric state. Unlike PHD3, neither Siah2 nor PHD1 or PHD2 exhibit change in their distribution after hypoxia treatment.

Figure 7. Distribution of endogenous PHD3, PHD2, PHD1 and Siah2 in different molecular mass complexes.

(A–D) A498 cells were maintained at normoxia or exposed to hypoxia (1%) for 6 h and harvested. Cell lysates were separated on gel filtration column and analysed by immunoblotting (N, normoxia; H, hypoxia). Fraction numbers were indicated on top of each panel. The graphs depict quantified amounts of the proteins in the respective fractions.

Collectively, these findings indicate that lower oxygen tensions trigger the redistribution of PHD3 from the smaller to the larger molecular mass complexes, which could include other PHDs. Our finding also point to inverse correlation between the size of PHD3 complexes and their activity and stability. Co-localization of lower order PHD3 complexes with Siah2 coincides with degradation of the more active form of PHD3 under hypoxia.

DISCUSSION

The present study provides important new insight into the mechanism by which Siah2 limits the availability of PHD3 under hypoxia, thereby reflecting the dynamic, multi-faceted cellular response to hypoxia that leads to the stabilization and subsequent activation of the HIF-1α protein. Siah2-dependent ubiquitination and degradation of PHD3 promotes HIF-1α stabilization during mild hypoxia (>2%), a condition under which certain PHD enzyme activity would be retained. However, despite its association with all three PHDs, Siah2 primarily affects the stability of PHD3. Here, we demonstrate that the PHD3 can assemble into higher order complexes whose composition is controlled by the ambient oxygen tension. PHD3 is present in high-molecular-mass complexes, partly because of its ability to form complexes with PHDs; we expect that such complexes will also contain additional proteins that would influence PHD localization and activity, in part by possible association with additional regulatory components and possibly substrates. This finding suggests that the mechanism underlying reduced PHD3 activity in hypoxia can be attributed to (i) its redistribution into higher order complexes that exhibit less hydroxylase activity and (ii) the increased susceptibility to degradation by Siah2 within the more active low-molecular-mass complex. Thus heterodimers/multimers of PHD3 are expected to be less active and more stable. The hypoxia-induced shift of PHD3 into higher order complexes may therefore reinforce the intrinsic suppressive effect of low oxygen tensions on PHD activity to secure the reduced PHD activity in hypoxia, and to favour further the accumulation of HIF-1α under these conditions.

As the structure of Siah2 was solved as a homodimer [25,26], it is plausible that dimeric Siah2 exhibits a greater association with PHD3 in fraction 36 (160 kDa) where most of the Siah2 exists and PHD3 has higher activity as a PHD. Siah2 is also known to form relatively large molecular complexes through its adaptor protein SIP [8].

Of interest is to note that GST pull-down assay using GST–Siah2 identified that PHD3 in larger molecular mass complexes was efficiently captured by Siah2 (results not shown). However, size fractionation of cell lysate did not detect Siah2 within the large complexes, possibly due to our limited sensitivity, or increased Siah2 auto-ubiquitination within the higher-molecular-mass complexes. Therefore we cannot exclude the possibility that degradation of PHD3 by Siah2 may also occur within the high-molecular-mass complex. The assembly of RING finger E3 ligases into complexes that contain their substrates, but also deubiquitination enzymes and adaptor proteins, has been shown to affect degree of self versus targeted ubiquitination [i.e. Mdm2–p53–USP7 (ubiquitin specific peptidase 7)].

The formation of multimeric complexes containing PHD was previously predicted [23] and is consistent with similar changes that were shown for the related family members of collagen hydroxylases [24]. Similar to our finding, the assembly of higher order collagen hydroxylase-containing complexes was also found to serve as a mechanism to control the activity of this family of enzymes [27]. Given that the size of the complex coincides with the enzymatic activity of PHD3, it is important to identify the proteins contained within the large complex. Among those, one expects to find a component of the TriC chaperonin complex recently shown to associate with PHD3 [28], which formed a complex of approx. 900 kDa.

Of note, while the formation of high order complexes (PHD3 up-shift to the larger molecular mass) is consistent, the degree of the up-shift may vary, possibly due to changes in the relative oxygen levels during the in vitro fractionations. The latter may also point to the existence of other oxygen-sensitive factors that could contribute to the formation of high order complexes. While the present study highlights how hypoxia induces dynamic changes that contribute to PHD3 activity and limited availability by Siah2, other regulatory components that affect PHD3 and Siah2 activity are expected.

ΔPHD1 and ΔPHD2 formed heteromeric complexes with PHD3 more efficiently than did their full-length counterparts. Therefore both PHD1 and PHD2 whose N-terminal domain had been truncated were as susceptible to Siah2-mediated degradation as PHD3. In turn, the N-terminal portion of PHD1 or PHD2 appears to be important in regulating the ability of PHDs to form hetero-dimers or multimers, altering the susceptibility of PHDs to Siah2. Importantly, distribution of PHD1 and PHD2 following size fractionation was limited only to the lower-molecular-mass complexes of approx. 160 kDa. These observations highlight the principal mechanism underlying selective degradation of PHDs by Siah2. Existence of alternative spliced forms of PHDs has been described in [29,30]. Although these splicing variants result in changes within the internal domains of the protein, it is plausible that changes in the N-terminal region of PHDs could also occur as a result of alternative splicing, mutagenesis or alternative initiation start sites, each of which would render PHD1 and PHD2 more susceptible to Siah2's effects, or conversely, render PHD3 more stable.

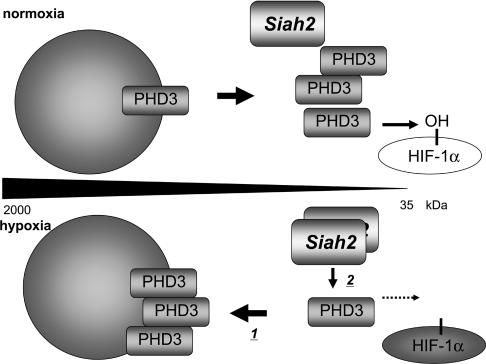

In summary, we have found that the PHD activity and stability of PHD3 are modulated by dynamic shifts between higher and lower order complexes, depending on the ambient oxygen tension (Figure 8). The assembly of these complexes could govern both the specific PHD activity of PHD3, and the susceptibility of PHD3 to Siah2-dependent degradation. Efforts to identify the additional components of the PHD3-containing complexes in normoxic and hypoxic cells will provide important insights into regulation of the PHDs themselves, and into the overall control of HIF-1α accumulation and function at various levels of tissue oxygenation.

Figure 8. Model for the regulation of PHD3 activity and stability in hypoxia.

In normoxia, PHD3 exists in low-molecular-mass species (monomer–dimer) and hydroxylates HIF-1α. During hypoxia, a portion of PHD3 is included in larger-molecular-mass complexes, where it reduces its activity (1), while PHD3 remaining in lower-molecular-mass species is targeted by Siah2 for degradation, which is also included in small complexes (2), thereby resulting in the overall pool of PHD3 being less available for modifying HIF-1α, and increases the pool of HIF-1α under hypoxia.

Acknowledgments

We thank David Bowtell for providing us with Siah constructs and cell lines, Peter Ratcliffe for PHD Abs, Mei Liu for anti-(HIF-1α hydroxylated Pro564) Ab, and Toshiya Tsuji for technical advice on the gel filtration experiment. We also thank members of the Ronai laboratory for discussions. K.N. was supported by a Japan Society for the Promotion of Science postdoctoral fellowship. Support by NCI grant RO1CA111515 (to Z.R.) is gratefully acknowledged.

References

- 1.Hershko A., Ciechanover A. The ubiquitin system. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 1998;67:425–479. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.67.1.425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Weissman A. M. Themes and variations on ubiquitylation. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2001;2:169–178. doi: 10.1038/35056563. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Li S., Li Y., Carthew R. W., Lai Z. C. Photoreceptor cell differentiation requires regulated proteolysis of the transcriptional repressor Tramtrack. Cell. 1997;90:469–478. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80507-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Tang A. H., Neufeld T. P., Kwan E., Rubin G. M. PHYL acts to down-regulate TTK88, a transcriptional repressor of neuronal cell fates, by a SINA-dependent mechanism. Cell. 1997;90:459–467. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80506-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Germani A., Bruzzoni-Giovanelli H., Fellous A., Gisselbrecht S., Varin-Blank N., Calvo F. SIAH-1 interacts with alpha-tubulin and degrades the kinesin Kid by the proteasome pathway during mitosis. Oncogene. 2000;19:5997–6006. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1204002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Habelhah H., Frew I. J., Laine A., Janes P. W., Relaix F., Sassoon D., Bowtell D. D., Ronai Z. Stress-induced decrease in TRAF2 stability is mediated by Siah2. EMBO J. 2002;21:5756–5765. doi: 10.1093/emboj/cdf576. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Matsuzawa S., Takayama S., Froesch B. A., Zapata J. M., Reed J. C. p53-inducible human homologue of Drosophila seven in absentia (Siah) inhibits cell growth: suppression by BAG-1. EMBO J. 1998;17:2736–2747. doi: 10.1093/emboj/17.10.2736. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Matsuzawa S. I., Reed J. C. Siah-1, SIP, and Ebi collaborate in a novel pathway for beta-catenin degradation linked to p53 responses. Mol. Cell. 2001;7:915–926. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(01)00242-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zhang J., Guenther M. G., Carthew R. W., Lazar M. A. Proteasomal regulation of nuclear receptor corepressor-mediated repression. Genes Dev. 1998;12:1775–1780. doi: 10.1101/gad.12.12.1775. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Nakayama K., Frew I. J., Hagensen M., Skals M., Habelhah H., Bhoumik A., Kadoya T., Erdjument-Bromage H., Tempst P., Frappell P. B., et al. Siah2 regulates stability of prolyl-hydroxylases, controls HIF1alpha abundance, and modulates physiological responses to hypoxia. Cell. 2004;117:941–952. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2004.06.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Epstein A. C., Gleadle J. M., McNeill L. A., Hewitson K. S., O'Rourke J., Mole D. R., Mukherji M., Metzen E., Wilson M. I., Dhanda A., et al. C. elegans EGL-9 and mammalian homologs define a family of dioxygenases that regulate HIF by prolyl hydroxylation. Cell. 2001;107:43–54. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(01)00507-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ivan M., Kondo K., Yang H., Kim W., Valiando J., Ohh M., Salic A., Asara J. M., Lane W. S., Kaelin W. G., Jr HIFalpha targeted for VHL-mediated destruction by proline hydroxylation: implications for O2 sensing. Science. 2001;292:464–468. doi: 10.1126/science.1059817. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jaakkola P., Mole D. R., Tian Y. M., Wilson M. I., Gielbert J., Gaskell S. J., Kriegsheim A., Hebestreit H. F., Mukherji M., Schofield C. J., et al. Targeting of HIF-alpha to the von Hippel–Lindau ubiquitylation complex by O2-regulated prolyl hydroxylation. Science. 2001;292:468–472. doi: 10.1126/science.1059796. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Semenza G. L. Targeting HIF-1 for cancer therapy. Nat. Rev. Cancer. 2003;3:721–732. doi: 10.1038/nrc1187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bruick R. K., McKnight S. L. A conserved family of prolyl-4-hydroxylases that modify HIF. Science. 2001;294:1337–1340. doi: 10.1126/science.1066373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Appelhoff R. J., Tian Y. M., Raval R. R., Turley H., Harris A. L., Pugh C. W., Ratcliffe P. J., Gleadle J. M. Differential function of the prolyl hydroxylases PHD1, PHD2, and PHD3 in the regulation of hypoxia-inducible factor. J. Biol. Chem. 2004;279:38458–38465. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M406026200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cioffi C. L., Liu X. Q., Kosinski P. A., Garay M., Bowen B. R. Differential regulation of HIF-1 alpha prolyl-4-hydroxylase genes by hypoxia in human cardiovascular cells. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2003;303:947–953. doi: 10.1016/s0006-291x(03)00453-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tuckerman J. R., Zhao Y., Hewitson K. S., Tian Y. M., Pugh C. W., Ratcliffe P. J., Mole D. R. Determination and comparison of specific activity of the HIF-prolyl hydroxylases. FEBS Lett. 2004;576:145–150. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2004.09.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Berra E., Benizri E., Ginouves A., Volmat V., Roux D., Pouyssegur J. HIF prolyl-hydroxylase 2 is the key oxygen sensor setting low steady-state levels of HIF-1alpha in normoxia. EMBO J. 2003;22:4082–4090. doi: 10.1093/emboj/cdg392. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Temes E., Martin-Puig S., Acosta-Iborra B., Castellanos M. C., Feijoo-Cuaresma M., Olmos G., Aragones J., Landazuri M. O. Activation of HIF-prolyl hydroxylases by R59949, an inhibitor of the diacylglycerol kinase. J. Biol. Chem. 2005;280:24238–24244. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M414694200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Inoue T., Geyer R. K., Howard D., Yu Z. K., Maki C. G. MDM2 can promote the ubiquitination, nuclear export, and degradation of p53 in the absence of direct binding. J. Biol. Chem. 2001;276:45255–45260. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M107477200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sengupta S., Wasylyk B. Ligand-dependent interaction of the glucocorticoid receptor with p53 enhances their degradation by Hdm2. Genes Dev. 2001;15:2367–2380. doi: 10.1101/gad.202201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ivan M., Haberberger T., Gervasi D. C., Michelson K. S., Gunzler V., Kondo K., Yang H., Sorokina I., Conaway R. C., Conaway J. W., et al. Biochemical purification and pharmacological inhibition of a mammalian prolyl hydroxylase acting on hypoxia-inducible factor. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2002;99:13459–13464. doi: 10.1073/pnas.192342099. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Myllyharju J., Kivirikko K. I. Collagens, modifying enzymes and their mutations in humans, flies and worms. Trends Genet. 2004;20:33–43. doi: 10.1016/j.tig.2003.11.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Polekhina G., House C. M., Traficante N., Mackay J. P., Relaix F., Sassoon D. A., Parker M. W., Bowtell D. D. Siah ubiquitin ligase is structurally related to TRAF and modulates TNF-alpha signaling. Nat. Struct. Biol. 2002;9:68–75. doi: 10.1038/nsb743. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Santelli E., Leone M., Li C., Fukushima T., Preece N. E., Olson A. J., Ely K. R., Reed J. C., Pellecchia M., Liddington R. C., et al. Structural analysis of Siah1–Siah-interacting protein interactions and insights into the assembly of an E3 ligase multiprotein complex. J. Biol. Chem. 2005;280:34278–34287. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M506707200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Vuori K., Pihlajaniemi T., Myllyla R., Kivirikko K. I. Site-directed mutagenesis of human protein disulphide isomerase: effect on the assembly, activity and endoplasmic reticulum retention of human prolyl 4-hydroxylase in Spodoptera frugiperda insect cells. EMBO J. 1992;11:4213–4217. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1992.tb05515.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Masson N., Appelhoff R. J., Tuckerman J. R., Tian Y. M., Demol H., Puype M., Vandekerckhove J., Ratcliffe P. J., Pugh C. W. The HIF prolyl hydroxylase PHD3 is a potential substrate of the TRiC chaperonin. FEBS Lett. 2004;570:166–170. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2004.06.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hirsila M., Koivunen P., Gunzler V., Kivirikko K. I., Myllyharju J. Characterization of the human prolyl 4-hydroxylases that modify the hypoxia-inducible factor. J. Biol. Chem. 2003;278:30772–30780. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M304982200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Cervera A. M., Apostolova N., Luna-Crespo F., Sanjuan-Pla A., Garcia-Bou R., McCreath K. J. An alternatively spliced transcript of the PHD3 gene retains prolyl hydroxylase activity. Cancer Lett. 2006;233:131–138. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2005.03.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]