Abstract

In glaucoma, retinal ganglion cells (RGCs) die by apoptosis, generally attributed to an elevated intraocular pressure (IOP). We now describe the impact of elevated IOP in the rat on expression of caspase 8 and caspase 9, initiators of the extrinsic and intrinsic caspase cascades, respectively. Activation of both caspases was demonstrated by the presence of cleaved forms of the caspases and the detection of cleaved Bid and PARP, downstream consequences of caspase activation. Surprisingly, the absolute level of procaspase 9 was also elevated after 10 days of increased IOP. To examine the cause of increased levels of the procaspase, we used laser capture microdissection to capture Fluorogold back-labeled RGCs and real-time polymerase chain reaction to measure mRNA changes of initiating caspases. The mRNA levels of both caspase 8 and caspase 9 were increased specifically in RGCs. These data suggest that elevated IOP activates a transcriptional up-regulation and activation of initiating caspases in RGCs and triggers apoptosis through both extrinsic and intrinsic caspase cascades.

The pathological hallmark of glaucoma is atrophy of the optic nerve associated with retinal ganglion cell (RGC) death, leading to vision loss and blindness throughout decades. The major risk factor for developing glaucoma is increased intraocular pressure (IOP). RGCs have been shown to die by apoptosis in both human1,2 and animal models3–5 although the exact mechanism(s) by which RGC apoptosis occurs in response to increased IOP is unknown. Two distinct pathways of upstream, initiating caspases can each begin a cascade that leads to activation of downstream effector caspases resulting in apoptosis.6 Caspase 8 is the initial caspase activated by cleavage of procaspase 8 to the active form in response to extrinsic cell signaling, such as binding of receptors with death domains that interact with Fas-associated death domains (FADD).7 The mitochondrial stress pathway on the other hand, begins with the release of cytochrome c from mitochondria, which then interacts with Apaf-1, causing cleavage and activation of caspase 9.8 The extrinsic pathway (through the death receptors) and the intrinsic pathway (through the mitochondria) for apoptosis are capable of operating independently leading to the activation of downstream effector caspases, caspase 3, 6, and 7. Poly (ADP-ribose) polymerase (PARP) is a 116-kd nuclear protein that is involved in the repair of DNA and in differentiation and in chromatin structure formation. During the late stages of apoptosis, downstream caspases, such as caspase 3, cleave PARP to yield 85-kd and 25-kd fragments.9

It is unclear which of the specific upstream molecular events occur in the retina under conditions of elevated IOP. In one report, caspase 8 was shown by immunohistochemistry to be activated in RGCs in experimental glaucoma in the rat.10 In another report, we showed that caspase 9 is activated by immunohistochemistry in RGCs and by Western blot analysis under conditions of elevated IOP also in the rat.4 To better understand the molecular events involved in RGC death in experimental glaucoma we performed Western blot analysis of both the caspase 8 and caspase 9 pathways. We found evidence of activation of both the extrinsic and intrinsic pathways, leading to Bid cleavage and PARP cleavage. We also detected elevated levels of procaspase 9. To further investigate the role of increased synthesis of caspases as a response to increased IOP, we adapted the technique of laser capture microdissection (LCM) to isolate previously back-labeled RGCs. This was combined with real-time polymerase chain reaction (PCR) to study the transcriptional changes in caspase 8 and caspase 9 mRNA under conditions of elevated IOP. Both caspases have elevated levels of transcription, suggesting that a coordinated program of caspase transcriptional regulation is triggered by increased IOP.

Materials and Methods

Animals

All experiments were performed in compliance with the Association for Research in Vision on Ophthalmology Statement for the Use of Animals in Ophthalmic and Vision Research. Adult male Brown Norway rats (300 to 450 g; Charles River, Boston, MA) were used in this study. Six animals were used for histological study and 21 animals for Western blot.

Experimentally Induced Glaucoma

Unilateral elevation of IOP was produced by injecting hypertonic saline into aqueous veins, as previously described by Morrison and colleagues.11 Briefly, hypertonic 1.9 mol/L saline was injected into limbal aqueous humor collecting veins of the left eye (OS). The right, fellow, eye (OD) served as control. In cases in which the IOP was not elevated within 2 weeks, reinjection was performed in a different episcleral vein. A maximum of three injections was performed.

IOP Determination

All IOP measurements were performed with animals in the awake state between 10 a.m. and 2 p.m. to minimize diurnal variability in IOP. After applying a drop of 0.5% proparacaine local anesthesia, IOP was measured using a TonoPen XL tonometer (Medtronic Ophthalmics, Jacksonville, FL). Fifteen readings were taken for each eye and averaged. Baseline IOP was obtained on 3 consecutive days before the first saline injection, and three times per week thereafter. We subjected the animals to a 10-day period of elevated pressure exposure. The beginning of this interval was determined as the day before the first measured pressure elevation. After IOP had been elevated for 10 days, rats were sacrificed with CO2 asphyxiation, the eyes were rapidly removed, and the eye-cups or retinas were collected, either for immunohistochemistry, LCM, counting, or for Western blot. As a measure for IOP exposure we integrated IOP with time, which takes into account both the length and the degree of IOP exposure. Integrated IOP was calculated as the area under the time-pressure curve (experimental eye-control eye), beginning with the day of the first saline injection.

Back-Labeling of RGCs

Anesthesia was induced using a mixture of acepromazine maleate (1.5 mg/kg), xylazine (7.5 mg/kg), and ketamine (75 mg/kg) (all from Webster Veterinary Supply, Sterling, MA). Deeply anesthetized rats were placed in a stereotaxic apparatus (Kopf Instruments, Tujunga, CA) and the skin overlying the skull was incised and retracted. The skull was leveled using the lambda and bregma sutures as landmarks. A craniotomy was then performed and an injector lowered into the superior colliculus 5.3 mm posterior to bregma, 1.5 mm lateral to midline, and 4.8 mm ventral to the skull surface.12 Two μl of a 3% Fluorogold (Fluorochrome LLC., Denver, CO) solution in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) with 10% dimethyl sulfoxide was injected for 10 minutes. The procedure was repeated on the contralateral side of the brain. The skin was sutured closed, antibiotic ointment applied to the wound, and the animal returned to its cage after recovery from anesthesia.13 Animals were allowed to recover for 7 days before further experimental interventions to allow for adequate back-labeling of RGCs.

Tissue Preparation

For LCM, immunohistochemistry, and counting, animals were perfused with PBS followed by 4% paraformaldehyde in PBS. The eyes were enucleated, the anterior segments rapidly removed, postfixed in 4% paraformaldehyde for another 1 hour, and cryoprotected with serial sucrose dilutions. Eye cups were frozen in optimal cutting temperature compound (OCT) (Tissue-Tek; Miles Inc., Diagnostic Division, Elkhart, IN) and sectioned in their entirety at 16 μm. Approximately 400 sections/eye were mounted on Superfrost Plus slides (VWR company, West Chester, PA), and stored at −80°C.

For Western blot analysis, retinas were homogenized and lysed with buffer containing 1 mmol/L EDTA/EGTA/dithiothreitol, 10 mmol/L Hepes, pH 7.6, 0.5% IGEPAL, 42 mmol/L KCl, 5 mmol/L MgCl2, 1 mmol/L phenylmethyl sulfonyl fluoride, and 1 tablet of protease inhibitors (Complete Mini; Roche Diagnostics GmbH, Mannheim, Germany) per 10 ml of buffer. Samples were incubated for 15 minutes on ice, and then centrifuged at 21,000 rpm at 4°C for 30 minutes and the supernatant was stored at −80°C.

Immunohistochemistry and Stereological Assessment of RGC Number

Serial 16-μm-thick sections were cut through the entire retina, and every 18th section was stained using an anti-Fluorogold antibody. Briefly, tissue sections were incubated with a blocking solution of 1% bovine serum albumin for 1 hour at room temperature, and then incubated with primary antibody specific for Fluorogold (1:200, Fluorochrome LLC.) overnight at 4°C. The sections were rinsed three times in PBS, incubated with secondary antibody [goat biotinylated anti-rabbit IgG (1:500; Vector Laboratories, Inc., Burlingame, CA)] for 1 hour at room temperature, rinsed three times in PBS, and incubated in avidin-biotin-peroxidase complex (Vector Laboratories) in PBS for 1 hour at room temperature. Coloration was performed in double-distilled H2O containing diaminobenzidine and hydrogen peroxide. Methyl Green (Vector Laboratories) was used to counterstain the nuclei.

Estimation of the total number of RGCs in each retina was made with unbiased stereology using the optical dissector and the fractionator. This sampling technique is not affected by tissue volume changes and does not require reference volume determinations.14,15 A random number generator was used to determine the first section to be counted. Subsequent sections were selected systematically following a constant sampling intensity of every 18th section. Fluorogold-positive cells were counted using an Olympus C.A.S.T. system (version 2.3.1.2; Olympus, Albertslund, Denmark) composed of an Olympus BX51 microscope connected to an Olympus DP70 digital camera and a computer operated X-Y-Z step motor stage ProScan II (PRIOR Scientific, Rockland, MA). The area of the RGC layer was delineated and a three-dimensional counting frame with extended exclusionary lines was randomly placed within the RGC layer to mark the first area to be sampled. The frame was then systematically moved through the entire delineated RGC layer. The number of positive cells was then extrapolated according to a stereological algorithm.14,15 In control retinas, 5% of the area of the RGC layer was counted and in experimental glaucoma retinas 10% of the area of the RGC layer was counted on each sampled cross-section. This sampling intensity was adopted to achieve an acceptable coefficient of error16 and coefficient of variation17 for both control and experimental eyes.

Immunofluorescence staining for PARP was performed on retinal sections from normal and elevated IOP eyes. Sections were incubated with a primary antibody specific for cleaved PARP (1:100; Cell Signaling, Beverly, MA) at 4°C overnight, and detection was performed with Alexa 594-labeled anti-rabbit IgG (1:250; Molecular Probes, Eugene, OR). Fluorescence staining was detected using an Olympus fluorescence microscope.

Western Blot Analysis

The protein concentration of the supernatant from each retina was determined using the Bio-Rad DC Protein Assay reagents (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Hercules, CA). Proteins were separated on sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis gels (10 to 20% Tris-HCl Ready-Gels, Bio-Rad Laboratories). Twelve μg of total retinal protein were loaded per lane, transferred to a polyvinylidene difluoride membrane (Immobilon-P; Millipore, Bedford, MA), and blocked with 5% nonfat dry milk in 0.1% TBS-T. The primary antibodies used were: procaspase 8 (1:1000, SK441; gift from Dr. Frank Barone, SmithKline Beecham Pharmaceuticals, King of Prussia, PA), cleaved caspase 8 (1:200; Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA), Bid/tBid (R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN), procaspase 9/cleaved caspase 9 (1:1000; MBL, Nagoya, Japan), and PARP (1:1000; Cell Signaling). Secondary antibodies were rabbit peroxidase-conjugated (1:20,000; Jackson ImmunoResearch, West Grove, PA) and mouse peroxidase-conjugated (1:20,000, Jackson ImmunoResearch), respectively. After overnight incubation at 4°C membranes were washed with TBS-T and incubated for 1 hour in secondary antibody at room temperature. Labeled protein was detected using SuperSignal reagent (Pierce, Rockford, IL). Membranes were exposed to HyperFilm (Amersham Biosciences, Chicago, IL). α-Tubulin (1:2000; Abcam, Cambridge, UK) was used as a loading control. Densitometry was performed using ImageQuant 1.2 (Molecular Dynamics, Inc., Sunnyvale, CA).

LCM of Fluorogold-Labeled RGCs

Tissue sections were allowed to thaw at room temperature for 30 seconds before immersion in RNase-free PBS for 10 minutes to wash off the OCT. Tissue sections were then further dehydrated by serial immersions in 75%, 95%, and 100% ethanol for 2 minutes, followed by a 2-minute immersion in xylene. Tissue sections were then air-dried for 2 to 5 minutes at room temperature before commencing LCM (Arcturus PixCell IIe laser capture microdissection system; Arcturus, Mountain View, CA). A Cap-Sure Cleanup Pad (Arcturus) was used to remove any loose tissue on the slide. RGCs were identified by the presence of Fluorogold (excitation filter, 330 to 380 nm; barrier filter, 400 nm) back-labeling. Approximately 1000 RGCs from each eye were captured onto a single Cap-Sure MacroLCM Cap (Arcturus) using the following parameters: spot size, 7.5 μm; power, 65 mW; pulse duration, 750 μs. One thousand photoreceptors from each eye were also captured as control. Undesired tissue picked up by the LCM cap (caused by tissue-tissue binding) was removed using the RNase-free pressurized air (Promega, Madison, WI).

RNA Extraction and Reverse Transcription (RT)

The captured cells on each cap were lysed with 20 μl of extraction buffer for 30 minutes at 42°C, and centrifuged (12,500 × g) from the caps into microfuge tubes. Proteinase K buffer (Arcturus) was added to each 20 μl of cell extraction solution. The extraction solution was incubated at 55°C for 1 hour and subsequently the Proteinase K was inactivated at 95°C for 10 minutes. Isolated RGCs were processed for RNA extraction using the PicoPure RNA isolation kit (Arcturus) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. Briefly, the sample was loaded on a RNA spin column and washed several times. DNase (Qiagen, Valencia, CA) was added and the total cellular RNA was eluted from the column in 14 μl of elution buffer. RT was performed, according to the manufacturer’s specifications (Invitrogen Corp., Carlsbad, CA), using 14 μl of extracted RNA from each LCM sample and 200 U of Superscript RT polymerase (Invitrogen). To reduce the total volume of the cDNA samples, we precipitated the cDNA in ethanol. Briefly, 10 μl of 2 mol/L sodium acetate, 1 μl of 5 mg/μl glycogen, and 30 μl of water were added and vortexed. Subsequently, 600 μl of ice-cold 100% EtOH was added and the solution was placed on dry ice for 1 hour. The mixture was centrifuged for 45 minutes at 4°C (16,000 rpm). Finally the EtOH was removed and the pellet was allowed to dry before being resuspended in 10 μl of molecular biology grade water.

Design of Primers and Real-Time PCR

The primers were designed using Primer 3 (http://frodo.wi.mit.edu/cgi-bin/primer3/primer3_www.cgi) and the GenBank sequences for GAPDH, caspase 8, and caspase 9 (Table 1). PCR primers were designed to amplify 123-bp and 132-bp sequences for caspase 8 and caspase 9, respectively. mRNA extracted from Brown Norway rat spleen was reverse-transcribed and used as the reference sample for caspase 8 and caspase 9. Primer (Genelink, New York, NY) annealing temperatures were optimized before use (Table 1). All real-time PCR reactions were performed in a 50-μl mixture containing 25 μl SYBR Green PCR Master Mix (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA), 1 μl sample cDNA, 0.5 μl forward primer, 0.5 μl reverse primer (final concentration: 2 nmol/L), and 13 μl molecular biology grade water. A negative control consisting of water was included with each reaction set. All PCR reactions were done in duplicate. Real-time quantitation was performed using the Bio-Rad iCycler iQ system (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA). The fluorescence threshold value was calculated using the iCycle iQ system software. The parameters used for PCR reactions were: predenaturing time of 6 minutes at 95°C; followed by 60 amplification cycles [95°C, 30 seconds; annealing temperature varied according to primer (Table 1), 1 minute; and 72°C, 1.5 minutes]. Serial dilutions of rat spleen cDNA (reference samples) were used to establish the functional concentration range and individual calibration curves for every primer used in the PCR. The dilution factor was customized for different primers. The amount of DNA present in any given sample was normalized to the amount of DNA of the housekeeping gene glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH), reflecting the number of cells present in that sample.18 Real-time PCR was performed on both the experimental samples and reference samples. Relative values for target abundance in each experimental sample were then extrapolated from the standard curve generated from the reference sample. The expression level of the experimental eye was then calculated relative to the control eye. To confirm the identity of real-time PCR reaction products, the products were run on an Agilent DNA chip with the Agilent 2100 bioanalyzer (Agilent Technologies, Palo Alto, CA) to verify size. The PCR products were also purified using QIAquick PCR purification kit to remove contaminating DNA primers and submitted for direct sequencing to the Massachusetts Eye and Ear Infirmary Sequencing Core facility. The specificity of the sequence data was verified using a BLAST search (National Center for Biotechnology Information).

Table 1.

The Product Size and Annealing Temperature of the Primers Used for GAPDH, Caspase 8, and Caspase 9 Genes

| Gene | Accession number | Oligonucleotides used for real-time polymerase chain reaction (PCR) primer sequence 5′ to 3′ | Annealing temperature (°C) | Product size (bp) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| GAPDH | AF106860 | F | GGCATTGCTCTCAATGACAA | 62 | 223 |

| R | TGTGAGGGAGATGCTCAGTG | 62 | |||

| Caspase 8 | AF288372 | F | CTGGGAAGGATCGACGATTA | 62 | 123 |

| R | CATGTCCTGCATTTTGATGG | 62 | |||

| Caspase 9 | NM031632 | F | AGCCAGATGCTGTCCCATAC | 55 | 132 |

| R | CAGGAGACAAAACCTGGGAA | 55 |

Statistical Analysis

NCSS (NCSS Statistical Software, Kaysville, UT) was used to perform all statistical analysis. Results are expressed as average ± SD. Significance was assessed at the 0.05 level.

Results

IOP History

The average IOP was 18.2 ± 0.8 mmHg for the control and 18.1 ± 0.7 mmHg for the experimental eye (n = 27) before any intervention. The control eye IOP remained unaffected during the experiment. The average peak IOP for the control and experimental eyes was 18.2 ± 1.1 mmHg and 43.2 ± 1.5 mmHg, respectively. The average integrated pressure-time difference between control and experimental eyes was 321.3 ± 52.2 mmHg-days (time frame from the day after surgery until sacrifice).

Cell Number

Fluorogold-positive cells in the RGC layer were counted from an average of 21 sections for each eye. Control retinas were estimated to have a total RGC count of 84,241 ± 5272 (n = 6; range, 78,000 to 91,440; coefficient of variation, 0.063; mean coefficient of error, 0.069) whereas experimental retinas were found to have 55,550 ± 3390 RGCs (n = 6; range, 51,000 to 58,764; coefficient of variation, 0.061; mean coefficient of error, 0.062). This translated into an average cell loss of 34% (range, 31 to 39%) after 10 days of elevated IOP (P < 0.05, one-sample t-test). An average of 237 ± 39 RGCs were counted in each eye (range, 184 to 314). Secondary analysis comparing cell loss in the peripheral to the central retina did not show a significant differential cell loss.

Evidence for Caspase 8 Activation in Experimental Glaucoma

We investigated protein level changes of caspase 8 in whole retinal lysates from rats exposed to 10 days of elevated IOP. Figure 1A shows Western blots of procaspase 8 protein (54 kd) and cleaved caspase 8 in retinas of eyes with elevated IOP (lanes 2 and 4) compared with control eyes with normal IOP (lanes 1 and 3). There was no increase in the protein level of procaspase 8 in this model at the 10-day time point (Student’s two-tailed t-test; P > 0.05, n = 21 animals). There was, however, a significant increase in cleaved caspase 8 protein levels in eyes with elevated IOP (Figure 1B) (P < 0.05, n = 21 animals).

Figure 1.

A: Procaspase 8, cleaved caspase 8, and tBid protein expression in whole retina after experimentally elevated IOP for 10 days. Elevated IOP resulted in an increase in caspase 8 cleavage and the presence of truncated Bid (lanes 2 and 4) compared to normal retinas (lanes 1 and 3). B: Quantification of the Western blots further confirmed that cleaved caspase 8 and tBid levels increase in elevated IOP retinas, however, procaspase 8 levels did not change significantly (n = 21, *P < 0.05).

We further investigated whether activation of caspase 8 lead to downstream caspase 8-mediated events in this model. One substrate of activated caspase 8 is Bid. Activation of caspase 8 causes the processing of Bid to generate a 15-kd fragment, tBid, which translocates to mitochondria and induces the release of cytochrome c thereby activating a mitochondrial apoptotic pathway.19 There were clear bands of tBid only in elevated IOP eyes (Figure 1A). The protein level of tBid increased after 10 days of elevated IOP to a level that was statistically significant (Student’s two-tailed t-test, P < 0.05, n = 6 animals) (Figure 1B).

Evidence for Caspase 9 Activation in Experimental Glaucoma

The results above show the activation of the caspase 8 pathway leading to downstream events. To extend our previous observations4 and further characterize the caspase 9 pathway, we performed immunoblot analysis on retinal protein lysates from rats with elevated IOP for 10 days. Figure 2A shows a representative example of the increase in procaspase 9 protein (45 kd) in retinas of eyes with elevated IOP (lanes 2 and 4) compared with control eyes with normal IOP (lanes 1 and 3). Figure 2B shows summary data from eyes with and without elevated IOP demonstrating a 150 ± 30% increase (n = 21, P < 0.05) in procaspase 9 protein levels in experimental retinas when compared with control retinas.

Figure 2.

A: Procaspase 9 and cleaved caspase 9 protein expression in whole retina after experimentally elevated IOP for 10 days. Elevated IOP resulted in an increase in procaspase 9 and cleaved caspase 9 (lanes 2 and 4) compared to normal retinas (lanes 1 and 3). B: Quantification of the Western blots further confirmed that procaspase 9 and cleaved caspase 9 levels increase in elevated IOP retinas significantly (n = 21, *P < 0.05).

We also quantified caspase 9 cleavage in retinal lysates by immunoblot analysis after 10 days of elevated IOP. Figure 2A shows a representative example of the appearance of the expected 35-kd active, cleaved caspase 9 in eyes with elevated IOP and the lack of cleaved caspase 9 in control eyes with normal IOP. Figure 2B shows summary data from eyes with and without elevated IOP demonstrating a 4.4 ± 0.6-fold (n = 21, P < 0.05) increase in caspase 9 cleavage in experimental glaucoma retinas when compared to control retinas.

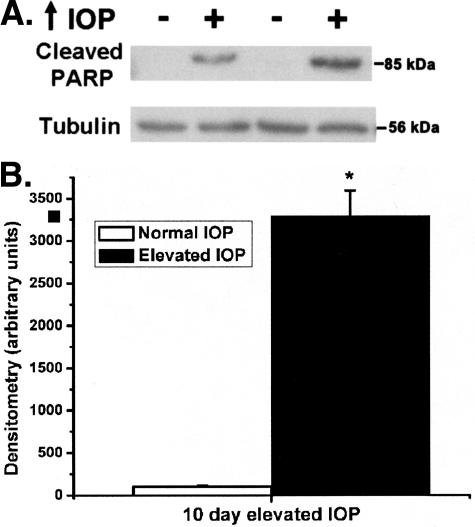

Retinal PARP Activation after Elevated IOP

To further investigate the downstream events after elevated IOP-initiated caspase activation we used Western blot analysis to examine PARP cleavage. Cleaved PARP bands were only seen in the eyes with elevated IOP (Figure 3A). The amount of cleaved PARP significantly increased in retinas after 10 days of elevated IOP (Figure 3B). The changes of PARP expression in elevated IOP eyes were further confirmed by immunohistochemistry on animals after 10 days of elevated IOP. In control retinas, there was only moderate PARP expression in the ganglion cell layer and inner nuclear layer (Figure 4). After 10 days of elevated IOP, there was a striking subcellular distribution change of PARP immunoreactivity in RGCs (Figure 4). In control retinas most of the immunoreactivity was perinuclear. After elevated IOP for 10 days there was an increase in nuclear PARP immunoreactivity in RGCs. A similar pattern of PARP immunoreactivity has been shown in RGCs after optic nerve axotomy by other researchers.20

Figure 3.

A: Cleaved PARP protein expression in whole retina after experimentally elevated IOP for 10 days. Cleaved PARP is only present in retinas with elevated IOP (lanes 2 and 4). B: Quantification of the Western blots further confirmed that PARP cleavage increase in elevated IOP retinas significantly (n = 21, *P < 0.05).

Figure 4.

PARP immunohistochemical staining of inner retina after 10 days of elevated IOP. A: Normal IOP retina. B: Elevated IOP retina. Arrows indicate baseline perinuclear staining and arrowheads indicate increased nuclear PARP immunoreactivity. GCL, ganglion cell layer; IPL, inner plexiform layer; INL, inner nuclear layer. Original magnifications, ×200.

Caspase 8 and Caspase 9 Message Levels Are Increased in Experimental Glaucoma

Activation of caspase 8 and the presence of tBid could lead to activation of downstream caspases and secondary activation of caspase 9, but cannot explain the elevation of procaspase 9 observed here or in our previous study.4 Some recent reports suggest that caspases can be transcriptionally regulated in addition to being involved in proteolytic activating cascades although this has not been previously examined in glaucoma. We therefore used real-time PCR to measure mRNA levels of caspase 8 and caspase 9 in experimental glaucoma. Because the majority of caspase activation occurs in RGCs in experimental glaucoma,4,10 we enriched the sample for real-time PCR by LCM of back-labeled RGCs. Figure 5 shows a rat retinal section from a control eye back-labeled with Fluorogold before (Figure 5A) and after LCM (Figure 5B). An image of the captured tissue on the cap, containing Fluorogold back-labeled RGCs, is shown in Figure 5C. Isolation efficiency was high with nearly all of the RGCs targeted by the laser being captured on the cap. The number of cells captured was recorded and the amount of mRNA calculated from an equal number of RGCs in control and elevated IOP samples.

Figure 5.

LCM of RGCs in the rat retina. Top: Intact retinal tissue back-labeled with Fluorogold. RGCs indicated by arrows. Center: Retinal tissue after LCM of the back-labeled RGCs using 7.5-μm diameter laser pulses. Tissue surrounding the extracted cells remains intact after the procedure. Arrows indicate prior positions of back-labeled RGCs. Bottom: Highly enriched population of LCM-captured back-labeled RGCs on the capture cap. GCL, ganglion cell layer; IPL, inner plexiform layer; INL, inner nuclear layer; ONL, outer nuclear layer.

LCM samples from six glaucoma rats were used to examine mRNA expression of caspase 8 and caspase 9 in RGCs. Caspase 8 and caspase 9 expression were both increased after experimental elevation of IOP for 10 days in all six animals (Table 2). The average experimental/control ratio was 3.3 ± 1 and 1.9 ± 0.6, respectively (P < 0.05, one-sample t-test). By contrast, LCM of photoreceptor cells captured in an analogous manner showed no significant change of caspase 8 (1.0 ± 0.1, n = 3) or caspase 9 (1.1 ± 0.1, n = 3) in comparing control and experimental eyes.

Table 2.

Caspase 8 and Caspase 9 mRNA Ratio of Experimental (OS) to Control (OD) Eye after 10 Days of Experimental Elevated IOP

| Target gene | Animal 1 OS/OD | Animal 2 OS/OD | Animal 3 OS/OD | Animal 4 OS/OD | Animal 5 OS/OD | Animal 6 OS/OD | Average OS/OD |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Caspase 8 | 5.1 | 2.0 | 3.4 | 3.3 | 2.7 | 3.3 | 3.3 ± 1.0* |

| Caspase 9 | 1.3 | 2.0 | 1.4 | 2.4 | 1.9 | 2.7 | 1.9 ± 0.6* |

GAPDH gene and cell number were used for normalization.

P < 0.05, one-sample t-test.

Discussion

In the present study, we characterized the two major upstream caspase cascades in response to elevated IOP. Earlier studies using cleavage-specific antibodies showed either cleaved caspase 8 in RGCs (immunohistochemistry)10 or cleaved caspase 9 in RGCs (immunohistochemistry)4 and retina (Western blot)4 in similar experimental glaucoma systems. Because each of the upstream caspases can initiate a distinct apoptotic pathway leading to caspase 3 activation, the question remained as to whether either or both initiator caspases were activated concurrently and played a role in triggering downstream pathways in experimental glaucoma. Our data support the idea that both are activated because we detect elevations in the cleaved (active) forms of both caspase 8 and caspase 9 as well as evidence of downstream apoptotic events including cleavage of Bid and PARP.

We also observed an increase in procaspase 9 levels after increased IOP. Although activation of tBid leads to its translocation to the mitochondria with subsequent release of cytochrome c and activation of the apoptosome (including secondary activation of caspase 9), activation of caspase 8 by itself could not directly account for the elevation of procaspase 9. This result was somewhat surprising because control of caspase activation is often thought of principally at the protein level with intricately controlled proteolytic cascades. To determine whether there was increased synthesis of procaspase 9 in RGCs in experimental glaucoma, we used LCM coupled with quantitative PCR. We show an increase in both caspase 8 and caspase 9 at the message level specifically in RGCs. These results suggest that transcription of apoptosis genes is increased in experimental glaucoma and directly implicate both caspase 8 and caspase 9, ie, both the extrinsic and intrinsic pathways, in RGC death (Figure 6). Our data emphasize that the transcriptional changes occur specifically in RGCs because photoreceptor cells did not show these changes.

Figure 6.

Proposed effects of elevated IOP on RGCs.

Although our data suggest that caspase 8 and caspase 9 are both activated in experimental glaucoma, they do not allow us to say whether they are activated sequentially or in parallel. Previous studies have highlighted the role of the intrinsic (caspase 9) cascade and BAX in RGC death. Decreasing BAX by a variety of methods has been demonstrated to lessen RGC death after optic nerve axotomy in rats and mice.21–23 These data are consistent with activation of the intrinsic pathway although a role for the extrinsic (caspase 8) pathway is not excluded because decreasing BAX does not completely abolish the RGC death in rat model systems.21,22

LCM is a powerful tool to isolate morphologically defined cell populations from histological slides under direct microscopic visualization.24 A significant problem when studying RGC-related ocular diseases is the heterogeneity of the retina because it consists of a mixture of photoreceptors, amacrine cells, endothelial cells, and pericytes making the investigation of RGC responses to injury difficult to ascertain when the whole retina is being used. Moreover, in disease models, loss of neurons targeted by the disease may introduce a bias against observing differences. Our approach overcomes two major technical problems: the overall small amount of RNA obtained with LCM, and the difficulty in identifying and quantifying the special cell types that need to be collected. In this study we used LCM to capture retrogradely labeled RGCs. Fluorogold labeling is a proven and successful method of distinguishing RGCs from other retinal cells.25 The combination of LCM with Fluorogold labeling enabled us to isolate a sample highly enriched in RGCs. We used both cell number (counted during capture) and normalization with a housekeeping gene as our loading control. Capturing a given number of RGCs and normalizing by GAPDH mRNA level ensured that we detected a specific RGC response without introducing bias caused by differential RGC proportion in control and experimental retina. On the other hand, it should be noted that we have captured surviving RGCs 10 days after initiating increased IOP, at a time when one-third of the RGCs have already undergone apoptosis; we postulate that neurons already gone may have had even higher responses of apoptotic cascades, so that our results showing marked up-regulation of caspase 8 and caspase 9 mRNA may underestimate the complete transcriptional effect of increased IOP.

Although acute caspase responses are regulated by posttranslational events involving cleavage cascades, recent data suggest that apoptotic stimuli can induce a coordinated transcriptional program of apoptosis-related genes. For example, treatment of cultured fibroblasts with advanced glycation end products results in an increase in caspase 8 and caspase 9 mRNA as well as an increase in their activity.26 Activation of p53-related mechanisms has also been directly shown to increase caspase 8 mRNA and initiate activation of both caspase 8 and caspase 9.27,28 Interestingly, there is a p53-responsive element in the caspase 8 promoter in both humans and rodents27 suggesting conservation of pathways to induce apoptosis related genes.

Our current results suggest that a coordinated program of transcriptional events leading to up-regulation of caspases occurs in experimental glaucoma. Study of the mRNA in RGCs may provide insight into the signal transduction pathways stimulated by elevated IOP that lead to RGC death.

Acknowledgments

We thank Bradley T. Hyman, M.D., Ph.D. (Department of Neurology, MassGeneral Institute for Neurodegenerative Disease, Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston, MA), for helpful comments and suggestions; and Charles R. Vanderburg, Ph.D. (Advanced Tissue Resource, Harvard Center for Neurodegeneration and Repair, Harvard Medical School, Boston, MA), for technical support.

Footnotes

Address reprint requests to Cynthia. L. Grosskreutz, Massachusetts Eye and Ear Infirmary, 243 Charles St., Boston, MA 02114. E-mail: cynthia_grosskreutz@meei.harvard.edu.

Supported by the National Institutes of Health (grant EY13399 to C.L.G. and core grant EY14104 to Massachusetts Eye and Ear Infirmary), Research to Prevent Blindness (career development award to C.L.G.), the Harvard University (Milton award to C.L.G.), the Kriezis Foundation (to T.F.); the Striebel Fund (to C.L.G.), and the Massachusetts Lion Eye Research Fund (to C.L.G.).

References

- Kerrigan LA, Zack DJ, Quigley HA, Smith SD, Pease ME. TUNEL-positive ganglion cells in human primary open-angle glaucoma. Arch Ophthalmol. 1997;115:1031–1035. doi: 10.1001/archopht.1997.01100160201010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wax MB, Tezel G, Edward PD. Clinical and ocular histopathological findings in a patient with normal-pressure glaucoma. Arch Ophthalmol. 1998;116:993–1001. doi: 10.1001/archopht.116.8.993. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garcia-Valenzuela E, Shareef S, Walsh J, Sharma SC. Programmed cell death of retinal ganglion cells during experimental glaucoma. Exp Eye Res. 1995;61:33–44. doi: 10.1016/s0014-4835(95)80056-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hanninen VA, Pantcheva MB, Freeman EE, Poulin NR, Grosskreutz CL. Activation of caspase 9 in a rat model of experimental glaucoma. Curr Eye Res. 2002;25:389–395. doi: 10.1076/ceyr.25.6.389.14233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quigley HA, Nickells RW, Kerrigan LA, Pease ME, Thibault DJ, Zack DJ. Retinal ganglion cell death in experimental glaucoma and after axotomy occurs by apoptosis. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 1995;36:774–786. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nunez G, Benedict MA, Hu Y, Inohara N. Caspases: the proteases of the apoptotic pathway. Oncogene. 1998;17:3237–3245. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1202581. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kruidering M, Evan GI. Caspase-8 in apoptosis: the beginning of “the end”? IUBMB Life. 2000;50:85–90. doi: 10.1080/713803693. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen M, Wang J. Initiator caspases in apoptosis signaling pathways. Apoptosis. 2002;7:313–319. doi: 10.1023/a:1016167228059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Verzola D, Gandolfo MT, Salvatore F, Villaggio B, Gianiorio F, Traverso P, Deferrari G, Garibotto G. Testosterone promotes apoptotic damage in human renal tubular cells. Kidney Int. 2004;65:1252–1261. doi: 10.1111/j.1523-1755.2004.00497.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McKinnon SJ, Lehman DM, Kerrigan-Baumrind LA, Merges CA, Pease ME, Kerrigan DF, Ransom NL, Tahzib NG, Reitsamer HA, Levkovitch-Verbin H, Quigley HA, Zack DJ. Caspase activation and amyloid precursor protein cleavage in rat ocular hypertension. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2002;43:1077–1087. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morrison JC, Moore CG, Deppmeier LM, Gold BG, Meshul CK, Johnson EC. A rat model of chronic pressure-induced optic nerve damage. Exp Eye Res. 1997;64:85–96. doi: 10.1006/exer.1996.0184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paxinos G, Watson C. San Diego: Academic Press; The Rat Brain in Stereotaxic Coordinates. 1998 [Google Scholar]

- Huang W, Hui Y, Zhang M. Retrograde labeling of adult rat retinal ganglion cells with the fluorogold. Yan Ke Xue Bao. 2000;16:29–33. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- West MJ, Gundersen HJ. Unbiased stereological estimation of the number of neurons in the human hippocampus. J Comp Neurol. 1990;296:1–22. doi: 10.1002/cne.902960102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- West MJ, Slomianka L, Gundersen HJ. Unbiased stereological estimation of the total number of neurons in the subdivisions of the rat hippocampus using the optical fractionator. Anat Rec. 1991;231:482–497. doi: 10.1002/ar.1092310411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glaser EM, Wilson PD. The coefficient of error of optical fractionator population size estimates: a computer simulation comparing three estimators. J Microsc. 1998;192:163–171. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2818.1998.00417.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tandrup T. Unbiased estimates of number and size of rat dorsal root ganglion cells in studies of structure and cell survival. J Neurocytol. 2004;33:173–192. doi: 10.1023/b:neur.0000030693.91881.53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vincent VA, DeVoss JJ, Ryan HS, Murphy GM., Jr Analysis of neuronal gene expression with laser capture microdissection. J Neurosci Res. 2002;69:578–586. doi: 10.1002/jnr.10329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferrer I, Planas AM. Signaling of cell death and cell survival following focal cerebral ischemia: life and death struggle in the penumbra. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol. 2003;62:329–339. doi: 10.1093/jnen/62.4.329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weise J, Isenmann S, Bahr M. Increased expression and activation of poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase (PARP) contribute to retinal ganglion cell death following rat optic nerve transection. Cell Death Differ. 2001;8:801–807. doi: 10.1038/sj.cdd.4400872. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lingor P, Koeberle P, Kugler S, Bahr M. Down-regulation of apoptosis mediators by RNAi inhibits axotomy-induced retinal ganglion cell death in vivo. Brain. 2005;128:550–558. doi: 10.1093/brain/awh382. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qin Q, Patil K, Sharma SC. The role of Bax-inhibiting peptide in retinal ganglion cell apoptosis after optic nerve transection. Neurosci Lett. 2004;372:17–21. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2004.08.075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Y, Schlamp CL, Poulsen KP, Nickells RW. Bax-dependent and independent pathways of retinal ganglion cell death induced by different damaging stimuli. Exp Eye Res. 2000;71:209–213. doi: 10.1006/exer.2000.0873. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simone NL, Bonner RF, Gillespie JW, Emmert-Buck MR, Liotta LA. Laser-capture microdissection: opening the microscopic frontier to molecular analysis. Trends Genet. 1998;14:272–276. doi: 10.1016/s0168-9525(98)01489-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levkovitch-Verbin H, Harris-Cerruti C, Groner Y, Wheeler LA, Schwartz M, Yoles E. RGC death in mice after optic nerve crush injury: oxidative stress and neuroprotection. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2000;41:4169–4174. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alikhani Z, Alikhani M, Boyd C, Nagao K, Trackman PC, Graves DT. Advanced glycation endproducts enhance expression of pro-apoptotic genes and stimulate fibroblast apoptosis through cytoplasmic and mitochondrial pathways. J Biol Chem. 2004;280:12087–12095. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M406313200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liedtke C, Groger N, Manns MP, Trautwein C. The human caspase-8 promoter sustains basal activity through SP1 and ETS-like transcription factors and can be up-regulated by a p53-dependent mechanism. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:27593–27604. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M304077200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burns TF, Bernhard EJ, El-Deiry WS. Tissue specific expression of p53 target genes suggests a key role for KILLER/DR5 in p53-dependent apoptosis in vivo. Oncogene. 2001;20:4601–4612. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1204484. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]