Abstract

There are three sites of m5U modification in Escherichia coli stable RNAs: one at the invariant tRNA position U54 and two in 23S rRNA at the phylogenetically conserved positions U747 and U1939. Each of these sites is modified by its own methyltransferase, and the tRNA methyltransferase, TrmA, is well-characterised. Two open reading frames, YbjF and YgcA, are approximately 30% identical to TrmA, and here we determine the functions of these candidate methyltransferases using MALDI mass spectrometry. A purified recombinant version of YgcA retains its activity and specificity, and methylates U1939 in an RNA transcript in vitro. We were unable to generate a recombinant version of YbjF that retained in vitro activity, so the function of this enzyme was defined in vivo by engineering a ybjF knockout strain. Comparison of the methylation patterns in 23S rRNAs from YbjF+ and YbjF– strains showed that the latter differed only in the lack of the m5U747 modification. With this report, the functions of all the E.coli m5U RNA methyltransferases are identified, and a more appropriate designation for YbjF would be RumB (RNA uridine methyltransferases B), in line with the recent nomenclature change for YgcA (now RumA).

INTRODUCTION

Transfer and ribosomal RNAs engage in a multitude of precisely coordinated molecular events during protein synthesis, the speed and accuracy of which are governed to a large extent by the ability of RNA to discriminate between functional and non-function interactions. The interactive and discrimatory abilities of RNA are determined by the four nucleotide components that make up its structure. The basic structural repertoire of RNA is expanded in tRNAs and rRNAs by a range of post-transcriptional modifications. These modifications are quite diverse in tRNAs, while rRNA modifications are generally limited to base and sugar methylations and pseudouridylation (1). Ribosomes of the enterobacterium Escherichia coli have 11 modified nucleotides in 16S rRNA and 23 modifications in 23S rRNA (2). Plotting the locations of the modified nucleotides onto the X-ray crystal structures of the ribosome (3–5) shows that they cluster within several discrete regions (6–8) that are concerned with subunit association, mRNA decoding, the binding of auxiliary factors, and peptide bond formation (9–12).

Although it is now generally agreed that all of the modifications within the E.coli rRNA have been comprehensively identified and mapped, several of the enzymes responsible for these modifications remain to be accounted for. To date, four of the 16S rRNA modification enzymes have been identified (13–16), while seven of the 23S rRNA enzymes are known (17–23). The incompletely characterised enzymes include those that convert uridine to thymidine (m5U), a modification that occurs in both rRNA and tRNAs. In E.coli, three RNA uridine nucleotides are converted to m5U: one is at the invariant tRNA position U54 (24,25); and the two other sites are at 23S rRNA nucleotides U747 and U1939 (26,27). The methyltransferase enzyme responsible for tRNA U54 methylation, TrmA, has been thoroughly investigated (28–31), whereas at the inception of our studies neither of the two rRNA m5U modifications had been linked to its cognate methyltransferase.

In an earlier study, a homology search of the then incomplete E.coli database revealed two open reading frames (YgcA and YbjF) with sufficient similarity to TrmA to warrant the authors’ conclusion that these represented the U747 and U1939 methyltransferases (32). Repeating the search in the completed E.coli genome sequence results in the same conclusion, without revealing additional m5U methyltransferase paralogues. Here, we have utilised Matrix Assisted Laser Desorption/Ionisation (MALDI) mass spectrometry to determine whether the putative m5U methyltransferases modify RNA transcripts in vitro. Using this approach, we have identified the methylation target of recombinant YgcA at U1939, consistent with the findings of Agarwalla et al. (21) published during the course of our studies. No recombinant versions of YbjF could be generated that showed in vitro activity. In this case a different approach, involving mass spectrometric comparison of the methylation patterns in 23S rRNAs from YbjF+ and YbjF– strains, was developed to define the activity of this enzyme in vivo.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Database searches

A BLAST search (33) restricted to the E.coli genome revealed two putative gene products, YgcA and YbjF, that have significant similarity to the tRNA m5U methyltransferase TrmA. After establishing that YgcA and YbjF are rRNA m5U methyltransferases, we used a standard BLASTp to screen for homologous sequences in other organisms. Sequences from the search that fulfilled the following four criteria were considered to be orthologues of the two E.coli rRNA m5U methyltransferases. First, sequences were required to have an expectation-value of <10–10 as defined by the BLAST program. Second, sequences had to contain all the four conserved m5U methyltransferase domains defined by Gustafsson et al. (32). Third, they were required to align throughout the entire sequence of YgcA or YbjF. Lastly, sequences exhibiting a higher score in a TrmA BLAST were considered to be tRNA rather than rRNA methyltransferases.

Bacterial strains, plasmids and growth conditions

The E.coli strains and plasmid used in this study are listed in Table 1. Strains were grown at 37°C in LB media or on LB-agar plates (34) containing, where appropriate, ampicillin at 100 µg/ml, kanamycin at 25 µg/ml or chloramphenicol at 25 µg/ml.

Table 1. Strains and plasmids used in the study.

| Strain/Plasmid | Description | Ref. |

|---|---|---|

| E.coli strains | ||

| CP79 | thr leu his argA RCrel F– | (25) |

| DH1 | F– supE44 recA1 endA1 gyrA96(Nalr) thi-1 hsdR17(rK– mK+) relA1 spoT1 | (34) |

| DH10B | F– mcrA Δ(mrr-hsdRMS-mcrBC) φ80dlacZΔM15 ΔlacX74 deoR recA1endA1 araD139Δ(ara, leu) 7697 galU galK λ– rpsL nupG | (55) |

| ER2566 | F– λ– fhuA2 [lon] ompT lacZ::T7 gene1 gal sulA11D(mcrC-mrr)114::IS10R(mcr-73::miniTn10–TetS)2 R(zgb-210::Tn10) (TetS) endA1 [dcm] | New England Biolabs |

| IB10 | thr leu his argARCrel F– rrmA | (25) |

| CP79 ΔybjF | thr leu his argARCrel F– ybjF | This study |

| IB10 ΔybjF | thr leu his argARCrel F– rrmA ybjF | This study |

| Plasmids | ||

| pTYB11 | Cloning/expression vector in T7 polymerase containing host. AmpR | New England Biolabs |

| pMAK705 | Ts replication origin. CmR | (41) |

| pOU12 | PQE60 derivative (Qiagen). AmpR | Lab. collection |

| PQErrmA | PQE60 derivative (Qiagen). AmpR and TetR | Lab. collection |

| pSD2KK | pGEM3 derivative (Promega). AmpR and KanR | Lab. collection |

| pMG25 | pUHE24-2 derivative (56). Cloning/expression vector. AmpR | Lab. collection |

| pCTM1 | ygcA gene cloned into the NcoI/BglII sites in pQErrmA. AmpR | This study |

| pCTM3 | ybjF gene cloned into the SphI/HindIII sites of Pou12. AmpR | This study |

| pCTM6 | trmA gene cloned into the EcoRI/BglII sites in pQErrmA. AmpR | This study |

| pCTM8 | TrmA in the EcoRI/HindIII sites of pMG25. AmpR | This study |

| pCTM9 | ygcA in the EcoRI/HindIII sites of pMG25. AmpR | This study |

| pCTM10 | ybjF in the EcoRI/HindIII sites of pMG25. AmpR | This study |

| pCTM11 | ybjF gene cloned into the SapI/EcoRI sites of pTYB11. AmpR | This study |

| pCTM12 | Kanamycin cassette from pSD2KK cloned into pCTM10. KanR and AmpR | This study |

| pCTM13 | ybjF gene containing KanR from pCTM12 cloned into pMAK705. KanR and CmR | This study |

Cloning of methyltransferase genes

The primers used for PCR amplification of methyltransferase genes (Table 2) were based on gene sequences in the E.coli genome database. Template DNA was obtained by suspending a small portion of a single colony of E.coli strain DH1 in 50 µl H2O and using 1 µl for each amplification reaction with the DNA polymerase Platinium Pfx (Life Technologies). PCR products were purified using High Pure PCR (Boehringer-Mannheim) and QIAEXII (Qiagen) kits. The ygcA, trmA and ybjF genes were inserted into the pQErrmA, pOU12 and pTYB11 cloning vectors to produce proteins with a C-terminal histidine (His-) tag, an N-terminal His-tag, and to form an intein fusion product, respectively (Table 1). Subcloning of tagged genes into plasmid pMG25 and transforming E.coli strain DH10B generally produced more efficient protein expression. DNA manipulations and cell transformation with plasmids were carried out using standard techniques (34). Restriction endonucleases and other enzymes for DNA manipulations (New England Biolabs and Roche Molecular Biochemicals) were used in accordance with the suppliers’ recommendations. Plasmids were prepared using a mini-prep kit (Bio-Rad), and cloned DNA fragments were sequenced using the CEQ 2000 Dye Terminator procedure (Beckmann).

Table 2. Oligodeoxynucleotides used in the study.

| Name | Sequence (5′ to 3′) | Purpose |

|---|---|---|

| TOFT-1 | GCTAAGATCTTTTAACGCGCGAGAAAAGTA | PCR ygcA 3′-end |

| TOFT-2 | CAGCTTAGCCATGGCGCAATTCTACTCTGC | PCR ygcA 5′-end |

| TOFT-3 | GCCGTAAGCATGCAGTGCGCACTTTACGA | PCR ybjF 5′-end. Knockout check |

| TOFT-4 | CGTTAGATCTTTGCTTCACCAGCAGCGTCA | PCR ybjF 3′-end. Knockout check |

| TOFT-5 | TATGTAAGCATGCATCACCATCACCATCACCAGTGCGCACTTTACGACGCG | PCR ybjF 5′-end. N-His-tag |

| TOFT-6 | CCACGTTAAGCTTTTGCTTCACCAGCAGCGTCAGCA | PCR ybjF 3′-end |

| TOFT-7 | CTACAGAATTCATTAAAGAGGAGAAATTAAATGACCCCCGAACACCTTCC | PCR trmA 5′-end |

| TOFT-8 | CACGTTAGATCTCTTCGCGGTCAGTAATACGC | PCR trmA 3′-end |

| TOFT-19 | TAATACGACTCACTATAGG | Top strand T7 transcription |

| TOFT-20 | GTCGGAACTTACCCGACAAGGAATTTCGCTACCTTAGGACCGTTATAGTTACGGCCCCTATAGTGAGTCGTATTA | T7 RNA transcript with U1939 |

| TOFT-21 | TGGAGGGGGCGAAGGGAATCGAACCCTCGTATAGTGCTTGGGAAGCTCTCGTTCTACCATTGAACTACGCCCCCCCTATAGTGAGTCGTATTA | T7 tRNA transcript with U54 |

| TOFT-31 | GGTGGTTGCTCTTCCAACATGCAGTGCGCACTTTACGA | PCR ybjF5′-end. Intein system |

| TOFT-32 | GGTGGTGAATTCTTGCTTCACCAGCAGCGTCA | PCR ybjF3′-end. Intein system |

| SD45 | GGCGCATCCGCTAATTTTTCAACATTAGTCCGTTCGGTCCTCCAGTTAGTGTTACCCAACCTTCAACCTGCTCCTATAGTGAGTCGTATTA | T7 RNA transcript with U747 |

Restriction sites and ATG start codons are in bold in the PCR primer sequences; sequences encoding His-tags are in italics.

Purification of methyltransferase enzymes

His-tagged proteins expressed in cells containing plasmids pCTM8, pCTM9 and pCTM10 were purified on Ni-agarose columns (Qiagen). Purified methyltransferases were dialysed against 20 mM Tris–Cl (pH 7.5), 10 mM magnesium acetate, 250 mM NH4Cl and 10% (w/v) glycerol to remove the imidazol from the elution buffer. The purity of the proteins was monitored by SDS–PAGE, and their sizes were checked against markers of comparable molecular weight (Pharmacia). The identities of the proteins were subsequently confirmed by peptide mapping using mass spectrometry (35).

For expression of the YbjF–intein fusion protein, E.coli strain ER2566 containing pCTM11 was grown overnight at 15–37°C in medium containing 0.4 mM isopropyl-d-thio-galactopyranoside. Cells were harvested and resuspended in 4 ml of 20 mM Tris–Cl (pH 8.0), 500 mM NaCl, 1 mM EDTA and 0.1% (w/v) Triton X-100 (lysis buffer) prior to sonication. Lysates were loaded onto a chitin column and washed twice with column buffer (lysis buffer without Triton X-100). Incubation in 10 ml column buffer containing 50 mM DTT at 4°C overnight induced cleavage at the intein site. The YbjF protein was eluted with column buffer, and its sequence and purity were checked as described above.

RNA substrates for methylation

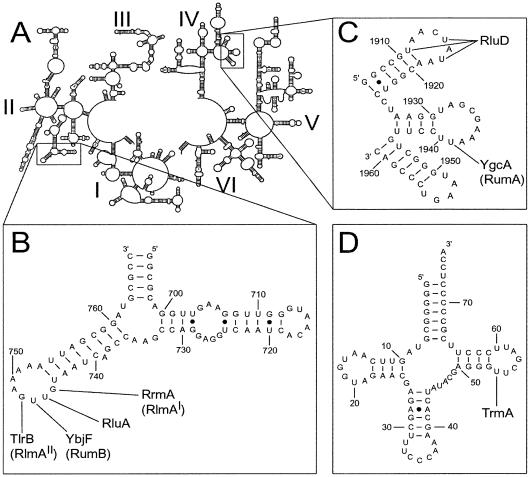

RNA transcripts used for in vitro methylation assays were synthesised from DNA oligodeoxynucleotide templates encoding the T7 RNA polymerase promoter (36,37). The DNA oligonucleotide TOFT21 encodes a full length tRNApro transcript containing the TrmA target at U54, and the oligodeoxynucleotides SD45 and TOFT20 encode the regions of E.coli 23S rRNA that contain the U747 and U1939 methylation targets, respectively (Table 2; Fig. 1). The RNA transcripts were purified on 10 µl reverse phase Poros 50R2 columns (PerSeptive Biosystems) made in-house (38).

Figure 1.

(A) Secondary structure of E.coli 23S rRNA (52,53); the domains are labelled with roman numerals. (B) RNA transcript corresponds to domain II nucleotides 694–767, and contains the U747 methylation target. Sites that are post-transcriptionally modified in vivo are indicated: RrmA (RlmAI) (17,37), RluA (18) and YbjF (RumB) (this study) are E.coli enzymes; TlrB (RlmAII) is found in Gram-positive bacteria (44). (C) RNA transcript of the three stem–loop structures corresponding to the domain IV sequence 1906–1961 and containing the U1939 target. Sites of modification in E.coli rRNA by RluD (54) and YgcA (RumA) (21 and this study), are shown. The terminal base pairs in transcripts (B) and (C) deviate from the E.coli 23S rRNA sequence to facilitate in vitro transcription and transcript folding. (D) RNA transcript mimicking the structure of E.coli tRNApro and containing the TrmA target at U54 (28).

Ribosomal particles from E.coli strains CP79, CP79ΔybjF, IB10 and IB10ΔybjF (Table 1) were fractionated on sucrose gradients, and 50S subunits were used to prepare 23S rRNA (39). All RNAs were redissolved and stored at –20°C in H2O (double distilled in all cases).

In vitro methylation

Purified RNAs (∼125 ng) were renatured in 50 µl of 100 mM NH4Cl, 20 mM Tris–Cl (pH 7.8), 10% (w/v) glycerol, 6 mM β-mercaptoethanol by warming for 5 min at 50°C followed by 10 min at 37°C. The methyl group donor, S-adenosylmethionine (SAM), was added to a final concentration of 1 mM; 1–50 ng of purified methyltransferases were added to start the methylation reactions, which proceeded for 30 min at 37°C. The reactions were stopped by extraction with phenol and chloroform; the RNAs were recovered from the aqueous phase by ethanol precipitation, and were redissolved in 2.5 µl H2O.

MALDI mass spectrometry analyses of RNAs

All the RNA methylation substrates were digested with ribonucleases to produce a discrete series of oligonucleotide fragments for analysis by mass spectrometry. 2.5 µl RNA (∼125 ng) was mixed with 0.5 µl 3-hydroxypicolinic acid (0.5 M in 50% acetonitrile) and 1.5 µl H2O, and was digested with 10 U RNase T1 (United States Biochemicals) for 3.5 h at 37°C. 3-hydroxypicolinic acid serves as a denaturing agent to ensure complete RNA digestion, in addition to functioning as a matrix for MALDI mass spectrometry (40).

23S rRNA was digested by incubating 2.0 µl RNA (∼260 ng) and 0.5 µl 0.5 M 3-hydroxypicolinic acid with 60 U of RNase T1 for 1 h at 37°C. Digestion products were run through Poros 50R2 columns (38), eluting short oligonucleotides with 10 mM triethyl ammonium acetate pH 7.0 (TEAA)/6% acetonitrile, and larger oligonucleotides with 10 mM TEAA/25% acetonitrile. Eluants were dried and redissolved in 3 µl H2O. The RNA digestion fragments were analysed on MALDI mass spectrometers from Bruker reflex IV (Bruker-Daltonik) or Voyager Elite (PerSeptive Biosystems), recording the spectra in reflector and positive ion mode using delayed ion extraction.

Knockout of the ybjF gene

The putative m5U methyltransferase gene ybjF was inactivated in the chromosome of E.coli strains CP79 and IB10 by insertion of a kanamycin resistance cassette. First, the kanamycin resistance cassette from plasmid pSD2KK was inserted in the BglII site of ybjF in pCTM10, creating pCTM12 (Table 1). The inactivated ybjF gene was excised from pCTM12 with SphI and EcoRV, and was ligated into the SphI/HincII sites of pMAK705, creating pCTM13. Plasmids pMAK705 and pCTM13 possess a temperature-sensitive pSC101 replicon (41); pCTM13 was used to transform strains CP79 and IB10 at the permissive temperature of 30°C. Double crossover recombination events between the genomic- and plasmid-encoded ybjF gene copies were facilitated by raising the incubation temperature to 42°C (41), and cells were then screened for kanamycin resistance and chloramphenicol sensitivity. The genomic ybjF region of potential knockout recombinants was analysed by PCR.

RESULTS

Expression, purification and activity of methyltransferases

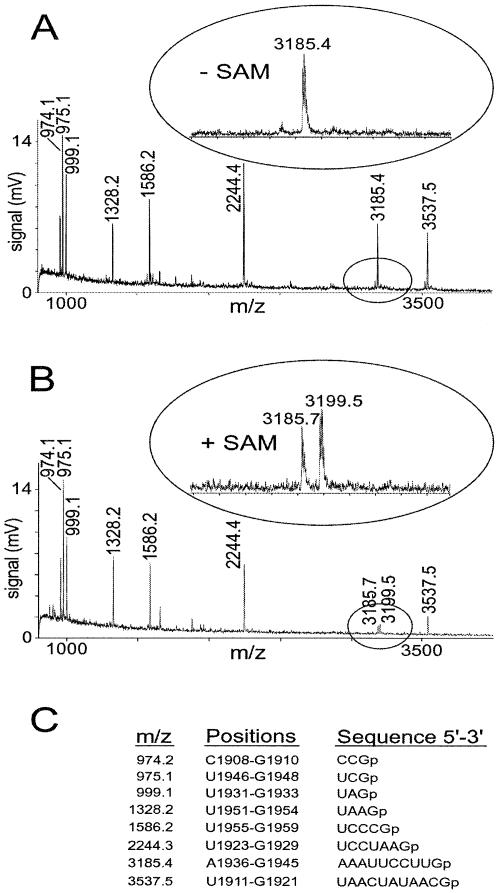

The cloned trmA, ygcA and ybjF genes were found to be identical to the sequences in the E.coli database (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/Genbank/index.html, ygcA GenBank accession no.: AE000362; ybjF, AE000187). Active, recombinant TrmA and YgcA proteins were purified with a C-terminal His-tag. The recombinant YgcA enzyme showed activity specific for the RNA substrate containing U1939 (Fig. 1C), with no cross-reactivity to the other RNA substrates. The RNase T1 oligonucleotide containing U1939 had an expected m/z of 3185.4 (Fig. 2A), and this peak was shifted to an m/z of 3199.5 after treatment of the RNA substrate with YgcA and the methyl group donor SAM (Fig. 2B). This increase in mass/charge of 14 Da is consistent with the addition of a single methyl group at U1939 by YgcA. Recombinant TrmA efficiently methylated its U54 target in the tRNA transcript (Fig. 1D), shifting the spectrum peak at m/z 1281.2 (UUCG) to 1295.0 (m5UUCG), and showed no cross-reactivity with the rRNA transcripts (data not shown).

Figure 2.

MALDI mass spectra of the U1939 RNA transcript after incubation with recombinant YgcA (RumA) followed by digestion with RNase T1. (A) Control sample without S-adenosylmethionine in the in vitro methylation assay (–SAM). (B) Test sample including the methyl group donor (+SAM). The spectral region around AAAUUCCUUGp is enlarged to show that this peak (theoretical m/z 3185.4) is shifted to m/z 3199.5 when the RNA is methylated. (C) Theoretical singly protonated masses of the RNase T1 digestion products from the U1939 RNA transcript. All measured masses are within 0.3 Da of the theoretical values. The jagged nature of the peaks visible in the enlargements reflects the natural isotopic distribution of 12C and 13C in the RNA.

Recombinant YbjF with a C-terminal His-tag could not be purified efficiently. Reasonable yields of the YbjF protein were obtained both with an N-terminal His-tag and using the intein fusion technique. However, no methylation of any of the transcripts was observed in vitro, including the RNA containing U747, which is otherwise an effective substrate for the RrmA and TlrB methyltransferases (37,42) (Fig. 1); recombinant YbjF also failed to transfer a tritiated methyl group from 3H-SAM to unmethylated 23S rRNA from strains CP79ΔybjF and IB10ΔybjF (data not shown). As we were probably inadvertently destroying the activity of YbjF at one of the in vitro steps, we elected to study the function of the protein in vivo.

The YbjF target in vivo

The ybjF gene was insertionally inactivated on the chromosome of the two E.coli strains CP79 and IB10. Potential ybjF knockout candidates were screened for kanamycin resistance (indicating the presence of the kanamycin resistance cassette in ybjF) and chloramphenicol sensitivity (showing that the plasmid initially harbouring the inactivated ybjF had been lost). Approximately 10% of the colonies that were screened displayed this phenotype, and PCR analysis of two candidates for each strain showed that the chromosomal copy of ybjF had been replaced by the inactivated plasmid copy (data not shown).

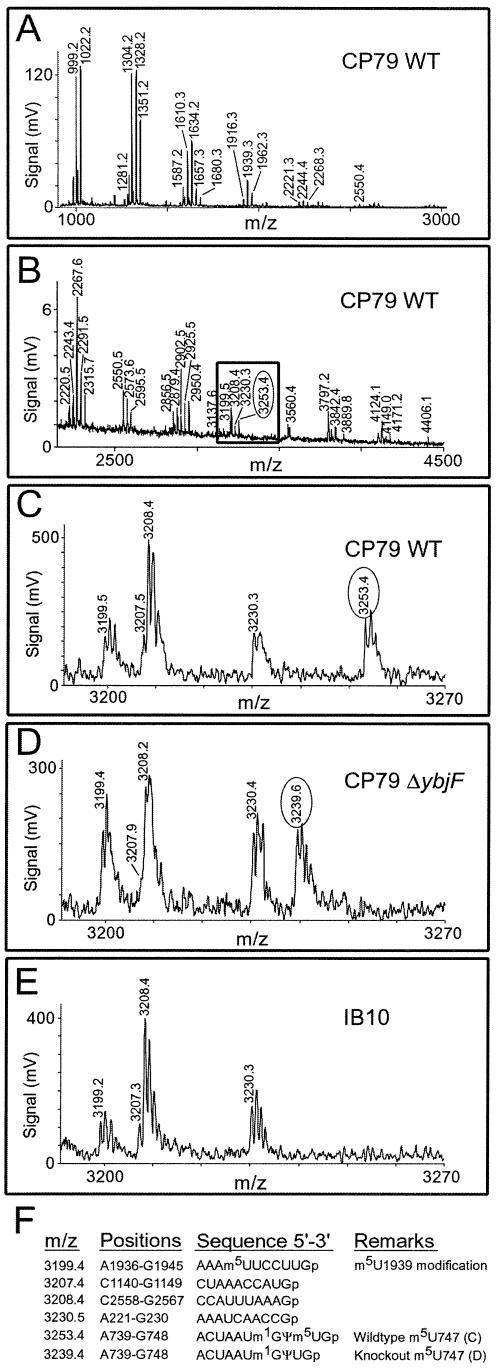

The 23S rRNAs were isolated from the four strains: CP79, IB10 and their ybjF knockouts. Strain IB10 has lost the function of RrmA (RlmAI) that methylates the N1 position of 23S rRNA nucleotide G745; CP79 is the parent strain with a functional RrmA (25). N1 methylation of G745 renders the nucleotide resistant to ribonuclease T1 digestion (43). Digestion of 23S rRNA with RNase T1 produces a complex array of oligonucleotides, which were purified and recorded in two separate mass spectra (Fig. 3A and B). In the high molecular weight spectrum of the wild-type 23S rRNA, a unique decanucleotide is seen with an m/z of 3253.4 spanning nucleotides 739–748 (Fig. 3C). In corresponding oligonucleotide spectrum from the CP79 ΔybjF strain, this peak is shifted to a lower m/z of 3239.6 (Fig. 3D). The loss of ∼14 Da indicates that a methyl group is missing from the 739–748 sequence in the ΔybjF strain.

Figure 3.

MALDI mass spectra of 23S rRNAs from CP79 wild-type (WT), CP79 ΔybjF and IB10 strains after digestion with RNase T1. Fragments arising from 5S rRNA do not appreciably complicate the spectrum and therefore have not been removed. Many oligonucleotides (particularly the smaller ones) have the same m/z values; all fragments of trinucleotides and larger are depicted here, and these have been eluted in two steps. (A) The smaller digestion products eluted with 6% acetonitrile; (B) larger oligo nucleotides eluted with 25% acetonitrile. (C) Enlargement of the boxed region shows that the wild-type double fragment 5′-ACUAAUm1Gψm5UGp (m/z 3253.4) is 14 Da heavier than in the ΔybjF strain (D). In the IB10 rRNA (E), the double fragment has been lost due to cleavage (see text). (F) The theoretical masses of protonated RNase T1 fragments of 23S rRNA in the region of interest; these match the measured m/z values to within 0.2 Da. The peak at m/z 3199.4 corresponds to a decanucleotide from 23S rRNA positions 1936–1945. This mass includes a methyl group, presumably at the YgcA target m5U1939, and is unaffected by inactivation of the ybjF gene. The spectra have been electronically smoothed using the Proteometrics Inc ‘m/z’ software program.

The site of YbjF methylation could be pinpointed using IB10 23S rRNA. Here, the unmethylated G745 is cleaved by RNase T1, and the 739–748 decanucleotide is therefore lost from the upper range of the MALDI spectrum (Fig. 3E). The resulting heptanucleotide, 5′-ACUAAUGp (nucleotides 739–745) comes to occupy the spectrum peak at 2268.3 (together with three other 23S rRNA fragments of identical m/z, (Fig. 3A). If the YbjF target lay within the 739–745 sequence, its m/z would be shifted to 2282.3 in the spectrum from the IB10 YbjF+ strain. The lack of a spectrum peak at m/z 2282.3 (not shown) makes it evident that the YbjF target resides within the trinucleotide 5′-U746-U747-Gp748. No methylation occurs at nucleotide U746, which is converted to pseudouridine by RluA (18) without changing the mass of the nucleotide (43); and no modification occurs at G748 in E.coli 23S rRNA (44). Thus the modification pattern of the trinucleotide is most consistent with the composition 5′-ψ746-m5U747-Gp748.

DISCUSSION

Three m5U modifications have previously been identified in E.coli: one at tRNA position 54, and two in 23S rRNA at positions 747 and 1939 (2). In this study we have used MALDI mass spectrometry to link the three sites of m5U modification with their respective methyltransferase enzymes. The tRNA m5U54 methyltransferase TrmA is known to retain its activity after purification (30,31), and the enzyme served as a positive control for our in vitro methylation assays. A search of the E.coli genome at the inception of our studies confirmed that the two most likely m5U rRNA methyltransferase candidates were YgcA and YbjF.

Recombinant YgcA proved to be as easy to purify and handle as TrmA, retaining its activity and specificity in vitro. YgcA specifically methylated an RNA transcript of 66 nucleotides, which was designed to mimic the structure around 23S rRNA nucleotide U1939 (Fig. 1C). Analysis of the 66mer after RNase digestion showed that YgcA increased the mass of the sequence 1936–1945 by 14 Da in the presence of the methyl group donor, SAM. This is consistent with the addition of a single methyl group at U1939 by YgcA. During the course of our study, Agarwalla and co-workers pinpointed the YgcA target at U1939 using biochemical approaches; they subsequently renamed this methyltransferase RumA (RNA uridine methyltransferase A) (21).

By a process of elimination, this left YbjF as the most likely candidate to target the U747 site. However, despite the construction of a variety of recombinant versions of YbjF and the use of different enzyme purification methods and RNA substrates, the study of YbjF function in vitro proved to be intractable. A second approach was taken, which involved analysis of authentic rRNA. The large subunit rRNAs (5S and 23S rRNAs) give rise to over 900 fragments upon RNase T1 digestion, and analysis of these required stretching the limits of the MALDI technology. Fortuitously, the putative target of YbjF occurs within the RNase T1 digestion product 5′-ACUAAUm1Gψm5UGp (nucleotides 739–748), which is a double fragment formed by virtue of the RNase-resistant m1G745 nucleotide. This fragment forms a distinct peak in the mass spectrum (Fig. 3C), the position of which is shifted 14 Da downstream corresponding to the loss of a single methyl group in the strain without a functional YbjF protein (Fig. 3D). The position of the methyl group added by YbjF could be localised within reasonable doubt to U747 by using strains that lack the m1G745 modification.

Most rRNA modifications are located within preserved, functionally important regions of the rRNA (6,7). The YgcA (RumA) target U1939 is phylogenetically conserved, with a uridine at this position in >95% of all organisms (Gutell Lab Comparative RNA: http://www.rna.icmb.utexas.edu). Similarly, YbjF (now RumB) targets a nucleotide that is conserved as a uridine in >95% of all bacteria, and in >90% of organisms in the other two phylogenetic domains (data from the Gutell web site).

Other enterobacteria possess homologues of rumA and rumB, and homologues are also evident in less closely related Gram-negative bacteria, as well as in phylogenetically distant species of archaea (Table 3). The conserved, methylated uridines are situated in regions of the 23S rRNA that have been associated with essential functions in protein synthesis. U1939 is located within the rRNA structure that interacts with the aminoacyl end of A-site bound tRNA (4,45), and could play an active role in sensing uncharged tRNA (21). U747 is situated in a highly conserved and densely modified part of the rRNA that lines a constricted region of the 50S subunit tunnel through which the nascent peptide chain passes during protein synthesis (3,5). This region of the tunnel additionally forms a binding pocket for macrolides and other antibiotics (39,46,47). Structural changes here confer antibiotic resistance (47,48), and can perturb regulatory interactions with the nascent peptide chain (49–51). Therefore, given its conservation and ribosomal location, the U747 methylation might be expected to be involved in one of more of these processes. However, in competition experiments run in rich and minimal media, we have not been able to detect any growth disadvantage for ybjF (rumB) knockout strains compared to the wild type (not shown). The presence of the U747 methylation could become important under specific growth or stress conditions, but definition of such a physiological role presently remains elusive.

Table 3. Homologues of YgcA(RumA) and YbjF(RumB).

| Identity/similarity score |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bacteria | Gene | GenBank accession no. | YgcA(RumA) | YbjF(RumB) |

| Shigella flexneri | ygcA | AE015293 | 99/99 | – |

| Shigella flexneri | ybjF | AE015110 | – | 98/99 |

| Salmonella enterica | ygcA | AE016843 | 84/91 | – |

| Salmonella enterica | ybjF | AE016840 | – | 88/92 |

| Salmonella typhimurium | ygcA | AE008835 | 84/91 | – |

| Salmonella typhimurium | ybjF | AE008737 | – | 87/92 |

| Shewanella oneidensis | SO3456 | AE015782 | 44/62 | – |

| Shewanella oneidensis | SO0980 | AE015542 | – | 56/73 |

| Haemophilus influenzae | HI0333 | U32718 | 46/65 | – |

| Haemophilus influenzae | HI0958 | U32777 | – | 54/70 |

| Pasteurella multocida | PM1866 | AE006224 | 44/62 | – |

| Pasteurella multocida | PM0070 | AE006042 | – | 56/70 |

| Vibrio cholerae | VC2452 | AE004315 | 48/63 | – |

| Vibrio cholerae | VCA0929 | AE004420 | – | 54/68 |

| Yersinia pestis | YPO1336 | AJ414147 | – | 74/83 |

| Haemophilus somnus | Hsom1363 | NZ_AABO02000010 | 46/62 | – |

| Pseudomonas fluorescens | Pflu2080 | NZ_AAAT02000042 | 42/57 | – |

| Pseudomonas syringae | Psyr2664 | NZ_AABP02000005 | 40/56 | – |

|

Azotobacter vinelandii |

Avin0974 |

NZ_AAAU02000022 |

40/57 |

– |

| Archaea | ||||

| Pyrococcus abyssi | PAB0719 | AJ248286 | 26/44 | 27/45 |

| Pyrococcus abyssi | PAB0760 | AJ248286 | 26/44 | 25/41 |

| Pyrococcus horikoshii | PH1137 | AP000005 | 28/46 | 27/47 |

| Pyrococcus horikoshii | PH1259 | AP000005 | 25/44 | 24/42 |

| Pyrococcus furiosus | PF1172 | AE010226 | 27/43 | 27/45 |

| Pyrococcus furiosus | PF0827 | AE010198 | 27/43 | 26/43 |

Homologues of E.coli YgcA(RumA) and YbjF(RumB) revealed in a BLASTp database search. Regions of similarity were found in 57 bacterial species, but only those with identities of >40% and which fulfilled the four criteria described in Materials and Methods are shown in the table. A dash (–) indicates an identity score of <25% compared to the other methyltransferase. Three species of the archaeon Pyrococcus are also listed with sequences similar to both RumA and RumB. These have a lower identity score than many of the bacteria and probably have a comparable, but not identical, function to the E.coli methyltransferases. The Pyrococcus PAB0719, PH1137 and PF1172 genes show >95% identity to each other, as do the PAB0760, PH1259 and PF0827 genes, but there is low similarity between the two groups. No clear homologues were found in other archaea or amongst eukaryotes.

Acknowledgments

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Søren Andersen from the Protein Research Group at University of Southern Denmark is thanked for performing the peptide mapping of the methyltransferases. Claes Gustafsson and Britt Persson are thanked for providing the IB10 and CP79 strains. Support from the Danish Biotechnology Instrument Centre (DABIC), the Danish Natural Sciences Research Council, the European Commission’s Fifth Framework Program (grant QLK2-CT2000-00935), the Carlsberg Foundation and the Nucleic Acid Centre of the Danish Grundforskningsfond is gratefully acknowledged.

REFERENCES

- 1.Bjork G.R., Ericson,J.U., Gustafsson,C.E., Hagervall,T.G., Jonsson,Y.H. and Wikstrom,P.M. (1987) Transfer RNA modification. Annu. Rev. Biochem., 56, 263–287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rozenski J., Crain,P.F. and McCloskey,J.A. (1999) The RNA Modification Database: 1999 update. Nucleic Acids Res., 27, 196–197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ban N., Nissen,P., Hansen,J., Moore,P.B. and Steitz,T.A. (2000) The complete atomic structure of the large ribosomal subunit at 2.4 Å resolution. Science, 289, 905–920. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Yusupov M.M., Yusupova,G.Z., Baucom,A., Lieberman,K., Earnest,T.N., Cate,J.H. and Noller,H.F. (2001) Crystal structure of the ribosome at 5.5 Å resolution. Science, 292, 883–896. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Schlunzen F., Zarivach,R., Harms,J., Bashan,A., Tocilj,A., Albrecht,R., Yonath,A. and Franceschi,F. (2001) Structural basis for the interaction of antibiotics with the peptidyl transferase centre in eubacteria. Nature, 413, 814–821. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Decatur W.A. and Fournier,M.J. (2002) rRNA modifications and ribosome function. Trends Biochem. Sci., 27, 344–351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Brimacombe R., Mitchell,P., Osswald,M., Stade,K. and Bochkariov,D. (1993) Clustering of modified nucleotides at the functional center of bacterial ribosomal RNA. FASEB J., 7, 161–167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hansen M.A., Kirpekar,F., Ritterbusch,W. and Vester,B. (2002) Posttranscriptional modifications in the A-loop of 23S rRNAs from selected archaea and eubacteria. RNA, 8, 202–213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Leviev I., Levieva,S. and Garrett,R.A. (1995) Role for the highly conserved region of domain IV of 23S-like rRNA in subunit-subunit interactions at the peptidyl transferase centre. Nucleic Acids Res., 23, 1512–1517. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Merryman C., Moazed,D., Daubresse,G. and Noller,H.F. (1999) Nucleotides in 23S rRNA protected by the association of 30S and 50S ribosomal subunits. J. Mol. Biol., 285, 107–113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wower J., Kirillov,S.V., Wower,I.K., Guven,S., Hixson,S.S. and Zimmermann,R.A. (2000) Transit of tRNA through the Escherichia coli ribosome. Cross-linking of the 3′ end of tRNA to specific nucleotides of the 23 S ribosomal RNA at the A, P and E sites. J. Biol. Chem., 275, 37887–37894. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Nissen P., Hansen,J., Ban,N., Moore,P.B. and Steitz,T.A. (2000) The structural basis of ribosome activity in peptide bond synthesis. Science, 289, 920–930. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wrzesinski J., Bakin,A., Nurse,K., Lane,B.G. and Ofengand,J. (1995) Purification, cloning and properties of the 16S RNA pseudouridine 516 synthase from Escherichia coli. Biochemistry, 34, 8904–8913. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gu X.R., Gustafsson,C., Ku,J., Yu,M. and Santi,D.V. (1999) Identification of the 16S rRNA m5C967 methyltransferase from Escherichia coli. Biochemistry, 38, 4053–4057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tscherne J.S., Nurse,K., Popienick,P. and Ofengand,J. (1999) Purification, cloning and characterization of the 16 S RNA m2G1207 methyltransferase from Escherichia coli. J. Biol. Chem., 274, 924–929. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.van Buul C.P. and van Knippenberg,P.H. (1985) Nucleotide sequence of the ksgA gene of Escherichia coli: comparison of methyltransferases effecting dimethylation of adenosine in ribosomal RNA. Gene, 38, 65–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gustafsson C. and Persson,B.C. (1998) Identification of the rrmA gene encoding the 23S rRNA m1G745 methyltransferase in Escherichia coli and characterization of an m1G745-deficient mutant. J. Bacteriol., 180, 359–365. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Raychaudhuri S., Niu,L., Conrad,J., Lane,B.G. and Ofengand,J. (1999) Functional effect of deletion and mutation of the Escherichia coli ribosomal RNA and tRNA pseudouridine synthase RluA. J. Biol. Chem., 274, 18880–18886. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Conrad J., Sun,D., Englund,N. and Ofengand,J. (1998) The rluC gene of Escherichia coli codes for a pseudouridine synthase that is solely responsible for synthesis of pseudouridine at positions 955, 2504 and 2580 in 23 S ribosomal RNA. J. Biol. Chem., 273, 18562–18566. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Huang L., Ku,J., Pookanjanatavip,M., Gu,X., Wang,D., Greene,P.J. and Santi,D.V. (1998) Identification of two Escherichia coli pseudouridine synthases that show multisite specificity for 23S RNA. Biochemistry, 37, 15951–15957. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Agarwalla S., Kealey,J.T., Santi,D.V. and Stroud,R.M. (2002) Characterization of the 23 S ribosomal RNA m5U1939 methyltransferase from Escherichia coli. J. Biol. Chem., 277, 8835–8840. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lovgren J.M. and Wikstrom,P.M. (2001) The rlmB gene is essential for formation of Gm2251 in 23S rRNA but not for ribosome maturation in Escherichia coli. J. Bacteriol., 183, 6957–6960. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Caldas T., Binet,E., Bouloc,P., Costa,A., Desgres,J. and Richarme,G. (2000) The FtsJ/RrmJ heat shock protein of Escherichia coli is a 23 S ribosomal RNA methyltransferase. J. Biol. Chem., 275, 16414–16419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Dunn D.B., Smith,J.D. and Spahr,P.F. (1960) Nucleotide composition of soluble ribonucleic acid from Escherichia coli. J. Mol. Biol., 2, 113–117. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bjork G.R. and Isaksson,L.A. (1970) Isolation of mutants of Escherichia coli lacking 5-methyluracil in transfer ribonucleic acid or 1-methylguanine in ribosomal RNA. J. Mol. Biol., 51, 83–100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hayashi Y., Osawa,S. and Miura,K. (1966) The methyl groups in ribosomal RNA from Escherichia coli. Biochim. Biophys Acta, 129, 519–531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Fellner P. (1969) Nucleotide sequences from specific areas of the 16S and 23S ribosomal RNAs of E.coli. Eur. J. Biochem., 11, 12–27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ny T. and Bjork,G.R. (1980) Cloning and restriction mapping of the trmA gene coding for transfer ribonucleic acid (5-methyluridine)-methyltransferase in Escherichia coli K-12. J. Bacteriol., 142, 371–379. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Persson B.C., Gustafsson,C., Berg,D.E. and Bjork,G.R. (1992) The gene for a tRNA modifying enzyme, m5U54-methyltransferase, is essential for viability in Escherichia coli. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA, 89, 3995–3998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Gu X.R. and Santi,D.V. (1991) The T-arm of tRNA is a substrate for tRNA (m5U54)-methyltransferase. Biochemistry, 30, 2999–3002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Santi D.V. and Hardy,L.W. (1987) Catalytic mechanism and inhibition of tRNA (uracil-5-)methyltransferase: evidence for covalent catalysis. Biochemistry, 26, 8599–8606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Gustafsson C., Reid,R., Greene,P.J. and Santi,D.V. (1996) Identification of new RNA modifying enzymes by iterative genome search using known modifying enzymes as probes. Nucleic Acids Res., 24, 3756–3762. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Altschul S.F., Madden,T.L., Schaffer,A.A., Zhang,J., Zhang,Z., Miller,W. and Lipman,D.J. (1997) Gapped BLAST and PSI-BLAST: a new generation of protein database search programs. Nucleic Acids Res., 25, 3389–3402. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sambrook J., Fritsch,E.F. and Maniatis,T. (1989) Molecular Cloning: A Laboratory Manual. 2nd Edn. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press, Cold Spring Harbor, New York, NY. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Jensen O.N., Larsen,M.R. and Roepstorff,P. (1998) Mass spectrometric identification and microcharacterization of proteins from electrophoretic gels: strategies and applications. Proteins, suppl. 2, 74–89. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Krupp G. and Soll,D. (1987) Simplified in vitro synthesis of mutated RNA molecules. An oligonucleotide promoter determines the initiation site of T7RNA polymerase on ss M13 phage DNA. FEBS Lett., 212, 271–275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hansen L.H., Kirpekar,F. and Douthwaite,S. (2001) Recognition of nucleotide G745 in 23 S ribosomal RNA by the rrmA methyltransferase. J. Mol. Biol., 310, 1001–1010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kirpekar F., Nordhoff,E., Larsen,L.K., Kristiansen,K., Roepstorff,P. and Hillenkamp,F. (1998) DNA sequence analysis by MALDI mass spectrometry. Nucleic Acids Res., 26, 2554–2559. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Hansen L.H., Mauvais,P. and Douthwaite,S. (1999) The macrolide-ketolide antibiotic binding site is formed by structures in domains II and V of 23S ribosomal RNA. Mol. Microbiol., 31, 623–631. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kirpekar F., Douthwaite,S. and Roepstorff,P. (2000) Mapping posttranscriptional modifications in 5S ribosomal RNA by MALDI mass spectrometry. RNA, 6, 296–306. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Hamilton C.M., Aldea,M., Washburn,B.K., Babitzke,P. and Kushner,S.R. (1989) New method for generating deletions and gene replacements in Escherichia coli. J. Bacteriol., 171, 4617–4622. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Liu M., Kirpekar,F., van Wezel,G.P. and Douthwaite,S. (2000) The tylosin resistance gene tlrB of Streptomyces fradiae encodes a methyltransferase that targets G748 in 23S rRNA. Mol. Microbiol., 37, 811–820. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Mengel-Jorgensen J. and Kirpekar,F. (2002) Detection of pseudouridine and other modifications in tRNA by cyanoethylation and MALDI mass spectrometry. Nucleic Acids Res., 30, e135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Liu M. and Douthwaite,S. (2002) Methylation at nucleotide G745 or G748 in 23S rRNA distinguishes Gram-negative from Gram-positive bacteria. Mol. Microbiol., 44, 195–204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Wower J., Hixson,S.S. and Zimmermann,R.A. (1989) Labeling the peptidyltransferase center of the Escherichia coli ribosome with photoreactive tRNA(Phe) derivatives containing azidoadenosine at the 3′ end of the acceptor arm: a model of the tRNA-ribosome complex. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA, 86, 5232–5236. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Moazed D. and Noller,H.F. (1987) Chloramphenicol, erythromycin, carbomycin and vernamycin B protect overlapping sites in the peptidyl transferase region of 23S ribosomal RNA. Biochimie, 69, 879–884. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Xiong L., Shah,S., Mauvais,P. and Mankin,A.S. (1999) A ketolide resistance mutation in domain II of 23S rRNA reveals the proximity of hairpin 35 to the peptidyl transferase centre. Mol. Microbiol., 31, 633–639. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Liu M. and Douthwaite,S. (2002) Resistance to the macrolide antibiotic tylosin is conferred by single methylations at 23S rRNA nucleotides G748 and A2058 acting in synergy. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA, 99, 14658–14663. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Gong F. and Yanofsky,C. (2002) Instruction of translating ribosome by nascent peptide. Science, 297, 1864–1867. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Nakatogawa H. and Ito,K. (2002) The ribosomal exit tunnel functions as a discriminating gate. Cell, 108, 629–636. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Tenson T. and Ehrenberg,M. (2002) Regulatory nascent peptides in the ribosomal tunnel. Cell, 108, 591–594. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Noller H.F. (1984) Structure of ribosomal RNA. Annu. Rev. Biochem., 53, 119–162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Gutell R.R., Larsen,N. and Woese,C.R. (1994) Lessons from an evolving rRNA: 16S and 23S rRNA structures from a comparative perspective. Microbiol. Rev., 58, 10–26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Gutgsell N.S., Del Campo,M.D., Raychaudhuri,S. and Ofengand,J. (2001) A second function for pseudouridine synthases: A point mutant of RluD unable to form pseudouridines 1911, 1915 and 1917 in Escherichia coli 23S ribosomal RNA restores normal growth to an RluD-minus strain. RNA, 7, 990–998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Grant S.G., Jessee,J., Bloom,F.R. and Hanahan,D. (1990) Differential plasmid rescue from transgenic mouse DNAs into Escherichia coli methylation-restriction mutants. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA, 87, 4645–4649. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Bujard H., Gentz,R., Lanzer,M., Stueber,D., Mueller,M., Ibrahimi,I., Haeuptle,M.T. and Dobberstein,B. (1987) A T5 promoter-based transcription-translation system for the analysis of proteins in vitro and in vivo. Methods Enzymol., 155, 416–433. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]