Abstract

To initiate studies on how protein-protein interaction (or “interactome”) networks relate to multicellular functions, we have mapped a large fraction of the Caenorhabditis elegans interactome network. Starting with a subset of metazoan-specific proteins, more than 4000 interactions were identified from high-throughput, yeast two-hybrid (HT=Y2H) screens. Independent coaffinity purification assays experimentally validated the overall quality of this Y2H data set. Together with already described Y2H interactions and interologs predicted in silico, the current version of the Worm Interactome (WI5) map contains ∼5500 interactions. Topological and biological features of this interactome network, as well as its integration with phenome and transcriptome data sets, lead to numerous biological hypotheses.

To further understand biological processes, it is important to consider protein functions in the context of complex molecular networks. The study of such networks requires the availability of proteome-wide protein-protein interaction, or “interactome,” maps. The yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae has been used to develop a eukaryotic unicellular interactome map (1-6). Caenorhabditis elegans is an ideal model for studying how protein networks relate to multicellularity. Here we investigate its interactome network with HT-Y2H.

As Y2H baits, we selected a set of 3024 worm predicted proteins that relate directly or indirectly to multicellular functions (7). Gateway-cloned open reading frames (ORFs) were available in the C. elegans ORFeome 1.1 (8) for 1978 of these selected proteins. Of these, 81 autoactivated the Y2H GAL1::HIS3 reporter gene as Gal4 DNA binding domain fusions (DB-X), and 24 others conferred toxicity to yeast cells. The remaining 1873 baits were screened against two different Gal4 activation domain libraries (AD-wrmcDNA and AD-ORFeome1.0), each with distinct, yet complementary, advantages (7).

We maximized the specificity of the Y2H system by applying stringent experimental and bioinformatics criteria (fig. S1). To eliminate interactions that originated from nonspecific promoter activation, we only considered DB-X-AD-Y pairs if they activated at least two out of three different Gal4-responsive promoters. Positives were subsequently retested in fresh yeast cells, and their AD-Y identities were determined with interaction sequence tags (ISTs) obtained by sequencing the corresponding polymerase chain reaction (PCR) products (9). The AD-Y reading frame was verified for each IST to avoid the recovery of out-of-frame peptides. In total, ∼16,000 ISTs were obtained.

Having applied those criteria, we subdivided the interactions into three confidence classes (fig. S1): those that were found at least three times independently and for which the AD-Y junction is in frame (“Core-1,” 858 interactions); those in frame found fewer than three times and that passed the retest (“Core-2,” 1299 interactions); and all other Y2H interactions found in our screens (“Non-Core,” 1892 interactions). The Core data set (Core-1 and Core-2) contains 2157 high-confidence interactions between 502 DB-X baits and 1039 AD-Y preys. After collapsing 22 interactions that occur in both DB-X-AD-Y and DB-Y-AD-X configurations, a total of 2135 unique interactions are obtained (table S1). The Non-Core data set contains 1892 interactions between 531 DB-X baits and 1395 AD-Y preys. Altogether, Core and Non-Core constitute the “First-Pass” data set, with a total of 4027 distinct interactions. Out of 2783 and 1505 interactions found with AD-wrmcDNA and AD-ORFeome1.0, respectively, 239 interactions were identified with both libraries.

To estimate the coverage of the HT-Y2H data sets, we manually searched the baits screened here for known interactors in WormPD (10). This search gave rise to 108 interactions, referred to as the “literature” data set (table S1). The Core and Non-Core data sets recapitulated eight and two interactions in this benchmark data set, respectively. Thus, our overall rate of coverage for the First-Pass data set is ∼10% [(8 + 2)/108)].

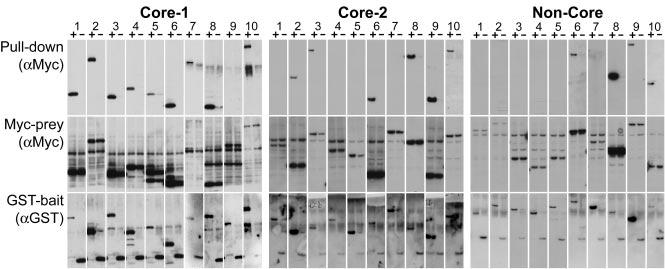

To evaluate the accuracy of the HT-Y2H data sets, we reasoned that interactions detected in two different binding assays are unlikely to be experimental false-positives. A representative sample of Y2H interaction pairs from each of these three subsets (33 for Core-1, 62 for Core-2, and 48 for Non-Core) was randomly selected, and tested in a coaffinity purification (co-AP) glutathione S-transferase (GST) pull-down assay (Fig. 1). Bait and prey ORFs were transiently transfected into 293T cells as GST-bait and Myc-prey fusions, respectively. For potential interaction pairs where both proteins were expressed at detectable levels, the co-AP success rates were 14 out of 17 (82%) for Core-1, 17 out of 29 (59%) for Core-2, and 8 out of 23 (35%) for Non-Core (table S2). These data demonstrate that our three data sets contain a large proportion of highly reliable interactions and corroborate their expected relative qualities.

Fig. 1.

Coaffinity purification assays. Shown are 10 examples from the Core-1, Core-2, and Non-Core data sets. The top panels show Myc-tagged prey expression after affinity purification on glutathione-Sepharose, demonstrating binding to GST-bait. The middle and bottom panels show expression of Myc-prey and GST-bait, respectively. The lanes alternate between extracts expressing GST-bait proteins (+) and GST alone (-). ORF pairs are identified in table S1 with the lane number corresponding to the order in which they appear in the table.

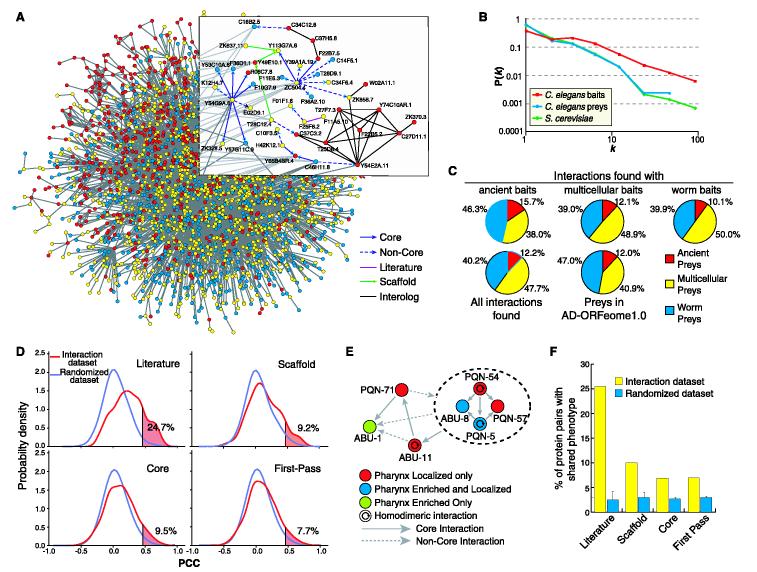

In addition to experimental screens, we also performed in silico searches for potentially conserved interactions, or “interologs,” whose orthologous pairs are known to interact in one or more other species (9,11). Starting from a high-confidence yeast interaction data set (7), reciprocal best-hit BLAST searches (E-value ≤ 10-6) were performed against the worm predicted proteome. In all, 949 potential worm interologs were identified, constituting the interologs data set (7). In addition, the Y2H interactome maps that have been previously generated for individual biological processes (including vulval development, protein degradation, DNA damage response, and germline formation) (9,12-14) were pooled to define the “scaffold” data set. The HT-Y2H, literature, interologs, and scaffold data sets were combined into Worm Interactome version 5 (WI5), containing 5534 interactions and connecting 15% of the C. elegans proteome (table S1). WI5 gives rise to a giant network component of 2898 nodes connected by 5460 edges (Fig. 2A). Similar to other biological networks (15), the worm interactome network exhibits small-world and scale-free properties (Fig. 2B) (7). This data set also allowed us to analyze whether or not evolutionary recent proteins tend to preferentially interact with each other rather than with ancient proteins. We subdivided the nodes of the network into three classes: 748 proteins with a clear ortholog in yeast (“ancient”), 1314 proteins with a clear ortholog in Drosophila, Arabidopsis, or humans but not in yeast (“multicellular”), and 836 proteins with no detectable ortholog outside of C. elegans (“worm”) (7). These three groups seem to connect equally well with each other (Fig. 2C), which suggests that new cellular functions rely on a combination of evolutionarily new and ancient elements, consonant with the classic proposal of evolution as a tinkerer that modifies and adds to pre-existing structures to create new ones (16).

Fig.2.

Analysis of the WI5 network. (A) Nodes (representing proteins) are colored according to their phylogenic class: ancient (red), multicellular (yellow), and worm (blue). Edges represent protein-protein interactions. The inset highlights a small part of the network. (B) The proportion of proteins, P(k), with different numbers of interacting partners, k, is shown for C. elegans proteins used as baits or preys and for S. cerevisiae proteins. (C) The pie charts show the proportion of interacting preys found in Y2H screens that fall into each phylogenic class. Also shown is the distribution of all preys found and all preys searched in the AD-ORFeome1.0 library. (D) Overlap with transcriptome (see text) (18), Pearson correlation coefficients (PCCs) were calculated and graphed for each pair of proteins in the interaction data sets and their corresponding randomized data sets. The red area to the right corresponds to interactions that show a significant relationship to expression profiling data (P < 0.05). (E) Interactions between proteins in Topomap mountain 29 (18). The dash-circled proteins belong to the same paralogous family (sharing more than 80% homology) and are thus collapsed into one set of interactions. (F) Proportion of interaction pairs where both genes are embryonic lethal (P < 10-7).

Previous studies have related interactome data with genome-wide expression (transcriptome) and phenotypic profiling (phenome) data in S. cerevisiae (17). To investigate to what extent different functional genomic assays should correlate in the context of a multicellular organism, we overlapped WI5 with C. elegans transcriptome and phenome data sets.

Based on a C. elegans transcriptome compendium data set (18), we calculated Pearson correlation coefficients (PCCs) for gene pairs involved in Y2H interactions and compared them with randomized data sets (Fig. 2D). About 150 Core interactions (9.5%) corresponded to gene pairs with significantly higher PCCs than expected from random (P < 0.05) (table S3). Thus, those pairs can be considered “more biologically likely” because two completely independent approaches point to a functional relationship between the corresponding genes. The remaining pairs are labeled “without additional evidence.” Indeed, it is important to note that lack of coexpression does not suggest that the corresponding interactions are irrelevant. Indeed, 75% of literature pairs, defined as biologically relevant, do not correlate with transcriptome data (Fig. 2D).

We also systematically examined Y2H interactions where both proteins belong to common C. elegans expression clusters, or “Topomap mountains” (18). As an example, a highly connected subnetwork derived from mountain 29 (Fig. 2E) contains seven proteins (ABU-1, ABU-8, ABU-11, PQN-5, PQN-54, PQN-57, and PQN-71) that share common domains (DUF139 domain and cysteine-rich repeat). Furthermore, these proteins are all expressed in the pharynx (19-21), which suggests that they may act together in pharynx function or development.

For relatively small-scale S. cerevisiae and C. elegans interactome data sets, physical interactions pointed to genes that share similar phenotypes when knocked out or knocked down (17). To evaluate this idea for the C. elegans interactome, we assembled a collection of phenotypic data based on RNA interference (RNAi) knockdown experiments from WormBase (7,22), and we calculated the percentage of protein interaction pairs that share embryonic lethal phenotypes for the interaction data sets and their randomized controls and found a twofold enrichment for the Core and First-Pass data sets (Fig. 2F). Similar correlations were also observed for the maternal sterile phenotype and four groups of postembryonic phenotypes (23). Because protein-protein interactions for which both genes are coexpressed across many conditions and show similar phenotype(s) when knocked down should be considered particularly likely, the global correlations described above illustrate how biological hypotheses can be derived from overlapping interactome, transcriptome, and phenome data sets (table S3).

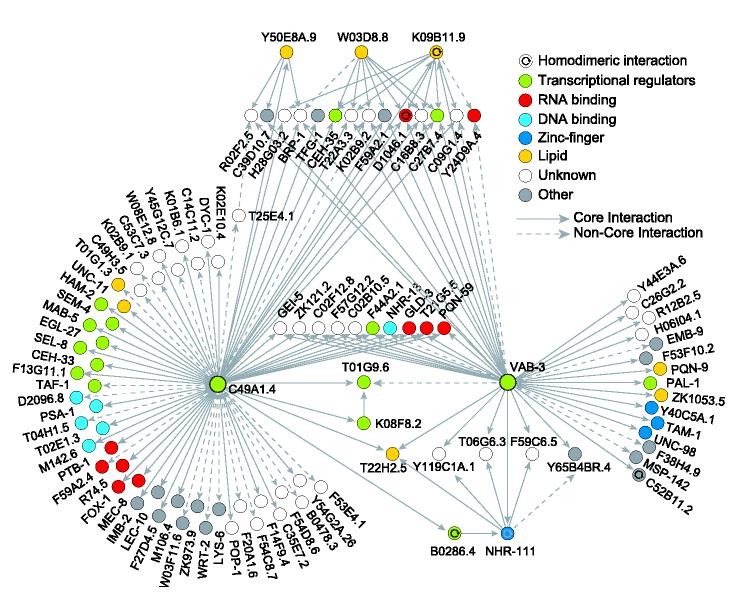

In S. cerevisiae, two proteins that have many interaction partners in common are more likely to be related biologically (24). We examined the C. elegans interactome network for the presence of highly connected neighborhoods by determining the mutual clustering coefficient between proteins in the network (table S4) (24). As an example, we examined the properties of one of the clusters containing such a high-scoring protein pair: VAB-3/C49A1.4 (Fig. 3). VAB-3 and C49A1.4 have strong similarity to the products of the Drosophila genes eyeless (ey) and eyes absent (eya), respectively, but not to each other. EY and EYA are components of a conserved network of transcription factors that regulate eye development (25).

Fig.3.

Graphical representation of a highly interconnected subnetwork around VAB-3 and C49A1.4. Biological functional classes were obtained from WormPD (10).

VAB-3 and C49A1.4 are part of a highly interconnected subnetwork in WI5 (Fig. 3) with proteins that are known or suspected to be functionally linked to VAB-3 and C49A1.4, or to their respective orthologs in other organisms. These include (i) EGL-27, which negatively regulates MAB-5 in hermaphrodites (26) and is linked to MAB-5 through C49A1.4; (ii) WRT-2, an interactor of C49A1.4 with similarity to Drosophila Hedgehog, which alleviates repression of eya expression by Cubitus interruptus (27); and (iii) CEH-33 and CEH-35, two of four members of the sine oculis homeobox gene family, which is involved in the same Drosophila regulatory network of transcription factors as ey and eya (28). Finally, eight proteins in this cluster are annotated in WormPD as involved in membrane function, which suggests a functional relationship between the eyeless transcription network and membrane activity.

Together with interologs and previously described interactions, the Y2H data set provides functional hypotheses for thousands of uncharacterized proteins in the C. elegans proteome. Integration with other functional genomic data indicates that the correlation between transcriptome and interactome data, although significant, is lower than what would be expected from observations made in yeast (17). This observation applies to both the Y2H data set described here and well-characterized worm interactions from the literature-derived data set (Fig. 2D). This may occur because, unlike unicellular organisms, metazoans are complicated by the fact that biological processes may occur differently in the organism, across various organs, tissues, or single cells.

Our current interactome map also illustrates how a human interactome project would benefit from an ORFeome cloning project using recombinational cloning systems, such as Gateway (8). Indeed, recombinationally cloned ORFs can be shuffled at will into various expression vectors needed for different types of protein interaction assays, as exemplified by our ability to transfer bait- and prey-encoding ORFs into Myc- and GST-tagged vectors to validate Y2H interactions.

Supplementary Material

References and Notes

- 1.Marcotte EM, et al. Science. 1999;285:751. doi: 10.1126/science.285.5428.751. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Pellegrini M, Marcotte EM, Thompson MJ, Eisenberg D, Yeates TO. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 1999;96:4285. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.8.4285. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Uetz P, et al. Nature. 2000;403:623. doi: 10.1038/35001009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ito T, et al. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2001;98:4569. doi: 10.1073/pnas.061034498. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ho Y, et al. Nature. 2002;415:180. doi: 10.1038/415180a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gavin AC, et al. Nature. 2002;415:141. doi: 10.1038/415141a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Science. See supporting material on. Online. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Reboul J, et al. Nat. Genet. 2003;34:35. doi: 10.1038/ng1140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Walhout AJM, Sordella R, Lu X, Hartley JL. Science. 2000;287:116. doi: 10.1126/science.287.5450.116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Costanzo MC, et al. Nucleic Acids Res. 2001;29:75. doi: 10.1093/nar/29.1.75. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Matthews LR, et al. Genome Res. 2001;11:2120. doi: 10.1101/gr.205301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Davy A, et al. EMBO Rep. 2001;2:821. doi: 10.1093/embo-reports/kve184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Boulton SJ, et al. Science. 2002;295:127. doi: 10.1126/science.1065986. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Walhout AJM, et al. Curr. Biol. 2002;12:1952. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(02)01279-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Strogatz SH. Nature. 2001;410:268. doi: 10.1038/35065725. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jacob F. Science. 1977;196:1161. doi: 10.1126/science.860134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ge H, Walhout AJM, Vidal M. Trends Genet. 2003;19:551. doi: 10.1016/j.tig.2003.08.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kim SK, et al. Science. 2001;293:2087. doi: 10.1126/science.1061603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gaudet J, Mango SE. Science. 2002;295:821. doi: 10.1126/science.1065175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hanazawa M, Mochii M, Ueno N, Kohara Y, Iino Y. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2001;98:8686. doi: 10.1073/pnas.141004698. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Urano F, et al. J. Cell Biol. 2002;158:639. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200203086. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Stein L, Sternberg P, Durbin R, Thierry-Mieg J, Spieth J. Nucleic Acids Res. 2001;29:82. doi: 10.1093/nar/29.1.82. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ge H. unpublished observations.

- 24.Goldberg DS, Roth FP. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2003;100:4372. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0735871100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wawersik S, Maas RL. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2000;9:917. doi: 10.1093/hmg/9.6.917. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ch’ng Q, Kenyon C. Development. 1999;126:3303. doi: 10.1242/dev.126.15.3303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Pappu KS, et al. Development. 2003;130:3053. doi: 10.1242/dev.00534. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Dozier C, Kagoshima H, Niklaus G, Cassata G, Burglin TR. Dev. Biol. 2001;236:289. doi: 10.1006/dbio.2001.0325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. We thank members of M.V.’s laboratory for their input and help; C. Boone, G. Achaz and D. Allinger for discussions; the sequencing staff at Agencourt Biosciences for technical assistance; the ORFeome meeting participants for their input; C. McCowan, T. Clingingsmith, and C. You for administrative assistance; and C. Fraughton for laboratory support. This work was supported by a grant from NHGRI and NIGMS awarded to M.V. Other support includes an NSF award (K.C.G.); NIGMS grants (S.v.d.H., S.E.M., J.W.H.); a Department of Defense Predoctoral Fellowship (B.B.); an award from the Ligue Nationale Contre Le Cancer (équipe labelisée) (C.S., A.C.); an institutional HHMI grant (F.P.R., G.F.B); and Fellowships from EMBO (P.-O.V.), NSF (D.S.G), Ryan, Milton (S.L.W.), Fu (L.V.Z.), and Leukemia Research Foundation (M.E.)

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.