Abstract

L-type, voltage-dependent calcium (Ca2+) channels, ryanodine-sensitive Ca2+ release (RyR) channels, and large-conductance Ca2+-activated potassium (KCa) channels comprise a functional unit that regulates smooth muscle contractility. Here, we investigated whether genetic ablation of caveolin-1 (cav-1), a caveolae protein, alters Ca2+ spark to KCa channel coupling and Ca2+ spark regulation by voltage-dependent Ca2+ channels in murine cerebral artery smooth muscle cells. Caveolae were abundant in the sarcolemma of control (cav-+/+) cells but were not observed in cav-1-deficient (cav-1−/−) cells. Ca2+ spark and transient KCa current frequency were approximately twofold higher in cav-1−/− than in cav-1+/+ cells. Although voltage-dependent Ca2+ current density was similar in cav-1+/+ and cav-1−/− cells, diltiazem and Cd2+, voltage-dependent Ca2+ channel blockers, reduced transient KCa current frequency to ∼55% of control in cav-1+/+ cells but did not alter transient KCa current frequency in cav-1−/− cells. Furthermore, although KCa channel density was elevated in cav-1−/− cells, transient KCa current amplitude was similar to that in cav-1+/+ cells. Higher Ca2+ spark frequency in cav-1−/− cells was not due to elevated intracellular Ca2+ concentration, sarcoplasmic reticulum Ca2+ load, or nitric oxide synthase activity. Similarly, Ca2+ spark amplitude and spread, the percentage of Ca2+ sparks that activated a transient KCa current, the amplitude relationship between sparks and transient KCa currents, and KCa channel conductance and apparent Ca2+ sensitivity were similar in cav-1+/+ and cav-1−/− cells. In summary, cav-1 ablation elevates Ca2+ spark and transient KCa current frequency, attenuates the coupling relationship between voltage-dependent Ca2+ channels and RyR channels that generate Ca2+ sparks, and elevates KCa channel density but does not alter transient KCa current activation by Ca2+ sparks. These findings indicate that cav-1 is required for physiological Ca2+ spark and transient KCa current regulation in cerebral artery smooth muscle cells.

Keywords: ryanodine-sensitive Ca2+ release channel, large-conductance Ca2+-activated potassium channel, caveolae, voltage-dependent Ca2+ channel

calcium (Ca2+) is a signaling messenger that regulates a wide variety of cellular functions, including secretion, proliferation, and contraction (2). To regulate specific Ca2+-dependent functions, cells can generate a variety of intracellular Ca2+ signals with distinct frequency, amplitude, and spatial-temporal characteristics.

Smooth muscle cells generate several different modes of Ca2+ signaling (15, 20). The global intracellular Ca2+ concentration ([Ca2+]i) arises because of extracellular Ca2+ influx and intracellular Ca2+ release. An elevation in global [Ca2+]i stimulates contraction, whereas a reduction in global [Ca2+]i results in relaxation. Localized [Ca2+]i transients, termed “Ca2+ sparks,” also occur in smooth muscle cells (20, 27). Ca2+ sparks occur due to the opening of several ryanodine-sensitive Ca2+ release (RyR) channels on the sarcoplasmic reticulum (SR) (15, 27). In smooth muscle cells, a Ca2+ spark does not directly elevate global Ca2+ but activates a number of nearby large-conductance Ca2+-activated potassium (KCa) channels, resulting in a transient KCa current. Membrane hyperpolarization induced by asynchronous transient KCa currents reduces voltage-dependent Ca2+ channel activity, leading to a decrease in global [Ca2+]i and relaxation. An elevation in [Ca2+]i activates Ca2+ sparks and transient KCa currents, forming a negative-feedback loop that limits Ca2+ entry through voltage-dependent Ca2+ channels (15, 27). Thus voltage-dependent Ca2+ channels, RyR channels, and KCa channels comprise a functional unit that regulates smooth muscle contractility (17). The differential regulation of contractility by local and global Ca2+ signaling is also effective because of differences in the frequency and amplitude of the Ca2+ signals and the Ca2+ sensitivities of the downstream targets for each signal mode (15). For local Ca2+ signaling mechanisms to operate, downstream targets must also be located in the proximity of the Ca2+ source. In smooth muscle cells, whether membrane proteins maintain spatial organization of voltage-dependent Ca2+ channels, KCa channels, and RyR channels to permit Ca2+ signaling between these proteins is unclear.

Compartmentalization of signaling molecules can occur in small, cholesterol-enriched, flask-shaped membrane invaginations termed “caveolae” (11, 13, 34, 39). Caveolins, of which three isoforms have been cloned (cav 1–3), are structural components required for caveolae formation (11, 13, 34, 39). Although all three caveolins have been identified in vascular smooth muscle cells, caveolin-1 is the primary isoform (9, 18, 28, 34, 39). Supporting a role for caveolae in the regulation of arterial smooth muscle local Ca2+ signaling is evidence that acute cholesterol depletion with dextrin inhibits Ca2+ sparks (23). Similarly, transient KCa current frequency is reduced in cerebral artery smooth muscle cells of cav-1-deficient (cav-1−/−) mice, when compared with wild-type controls (10). In ureter smooth muscle cells, KCa channels are found in buoyant membrane fractions, and in cultured myometrial cells KCa channels are localized to caveolae (1, 3). Thus cav-1 and caveolae may regulate Ca2+ sparks and KCa channels in smooth muscle.

Here, the communication between voltage-dependent Ca2+ channels and RyR channels that generate Ca2+ sparks and signaling between Ca2+ sparks and KCa channels was investigated in cerebral artery smooth muscle cells of cav-1+/+ and cav-1−/− mice. Data indicate that cav-1 ablation abolishes caveolae, elevates Ca2+ spark frequency, and attenuates Ca2+ spark regulation by voltage-dependent Ca2+ channels. In contrast, transient KCa current activation by Ca2+ sparks is unaltered in cav-1−/− cells, even though there is an increase in KCa channel density.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Tissue preparation

Animal procedures used were reviewed and approved by the Animal Care and Use Committee policies at the University of Tennessee. Age-matched (4–6 wk) cav-1−/− mice (Cav1tm1Mls, stock no. 004585; see Ref. 33) or wild-type control (cav-1+/+) mice were purchased from Jackson Laboratories (Bar Harbor, ME). Mice were killed by peritoneal injection of a pentobarbital sodium overdose (130 mg/kg). The brain was removed and placed into ice-cold (4°C) physiological saline solution (PSS) containing (in mM) 112 NaCl, 4.8 KCl, 26 NaHCO3, 1.8 CaCl2, 1.2 MgSO4, 1.2 KH2PO4, and 10 glucose and gassed with 74% N2-21% O2-5% CO2 (pH 7.4). Posterior cerebral, cerebellar, and middle cerebral arteries (∼150 μm in diameter) were removed, cleaned of connective tissue, and maintained in ice-cold Ca2+-free buffer (solution A) containing (in mM) 55 NaCl, 80 Na glutamate, 5.6 KCl, 2 MgCl2, 10 HEPES, and 10 glucose (pH 7.3 with NaOH). For single cell isolation, smooth muscle cells were dissociated from cerebral arteries with the use of enzymes, as previously described (14).

Electron microscopy

The brain was fixed in PSS containing 2.5% glutaraldehyde for 1 h. Cerebral arteries were dissected from the fixed brain, cleaned of connective tissue, and postfixed in 1% osmium tetroxide in PSS for 4 h. Arteries were then rinsed briefly in deionized water and en bloc stained with 2% uranyl acetate in 0.85% sodium chloride overnight at 4°C. Arteries were dehydrated in graded solutions of ethanol, from 30% through 100% for 1 h each, infiltrated with 50% Spurr in 100% ethanol overnight at room temperature, 100% Spurr over an 8-h period involving at least three changes of Spurr, and then cured at 60°C for 2 days. Transverse sections (75 nm) were cut with a Reichert Ultracut E microtome and poststained with uranyl acetate and lead citrate. Cells were observed and photographed with a JEOL 2000EX TEM located in the Electron Microscope Facility at the University of Tennessee Health Science Center.

Patch-clamp electrophysiology

Potassium currents were measured by using the conventional whole cell, perforated-patch or inside-out patch-clamp configurations with an Axopatch 200B amplifier and Clampex 8.2 (Axon Instruments, Union City, CA). For transient KCa current measurement, the bath solution (solution B) contained (in mM) 134 NaCl, 6 KCl, 2 CaCl2, 1 MgCl2, 10 HEPES, and 10 glucose (pH 7.4 with NaOH), and the pipette solution contained (in mM) 110 potassium aspartate, 30 KCl, 10 NaCl, 1 MgCl2, 10 HEPES, and 0.05 EGTA (pH 7.2 with KOH). Amphotericin B (Sigma) was dissolved in DMSO and diluted into the pipette solution to give a final concentration of 200 μg/ml. For whole cell K+ current measurement, the bath solution was solution B and the pipette solution contained (in mM) 135 KCl, 5 EGTA, 1.0 BAPTA, 3.5 MgCl2, 2.5 Na2ATP, and 10 HEPES (pH 7.2 with KOH). For inside-out patch-clamp experiments to measure single KCa channel currents, the pipette and bath solution both contained (in mM) 140 KCl, 10 HEPES, 5 EGTA, and 1.6 1-N-(2-hydroxyethyl)ethylenediamine-N,N′,N′-triacetic acid (pH 7.2 with KOH). MgCl2 and CaCl2 were supplemented to bath solution to provide 1 mM free Mg2+ and the required free Ca2+ concentration (1–100 μM). Free Ca2+ concentration in the pipette solution was 10 μM. Free Ca2+ concentrations were measured by using a Ca2+-sensitive and reference electrode (Corning). For voltage-dependent Ba2+ current measurements, the pipette solution contained (in mM) 125 CsCl, 20 tetraethylammonium chloride (TEACl), 1.0 MgCl2, 0.5 EGTA, 10 HEPES, and 10 glucose (pH 7.2 with CsOH), and the bath solution contained (in mM) 60 NaCl, 60 TEACl, 1.0 MgCl2, 20 BaCl2, 10 glucose, and 10 HEPES (pH 7.4 with NaOH). Pipette resistance was measured by applying a 5-mV pulse using the seal test function of pClamp 8.2. Transient KCa currents were measured at a steady membrane potential of −40 mV. Voltage-dependent Ba2+ currents were activated from a holding potential of −80 mV by applying 300-ms voltage steps to voltages between −50 and +60 mV in increments of 10 mV. Whole cell K+ (Ik) currents were activated from a holding potential of −80 mV by applying 250-ms voltage steps to voltages between −70 and +80 mV in 10-mV increments. In inside-out patches, single KCa channel currents were measured at steady voltages of −40 or +40 mV. Transient KCa currents were filtered at 1 kHz and digitized at 5 kHz. Voltage-dependent Ba2+ currents were filtered at 1 kHz and digitized at 4 kHz. Other current measurements were filtered at 2 kHz and digitized at 10 kHz. Transient KCa current analysis was performed off-line using methodology described elsewhere (6). A transient KCa current was defined as the simultaneous opening of three or more KCa channels. Open probability (Po) was calculated from the following equation: Po = (∑tii)/nT, where ti is the time at each channel level i, n is the number of channels in the patch, and T is the total time of analysis. The total number of KCa channels in an inside-out patch was determined at a voltage of +40 mV with 100 μM free Ca2+ in the bath solution. In each patch under each condition, at least 5 min of continuous data were analyzed to calculate transient KCa current frequency and amplitude, and 2–5 min were analyzed to determine single KCa channel open probability.

Confocal Ca2+ imaging

Isolated smooth muscle cells were incubated in solution A containing fluo-4 AM (10 μM) for 20 min at room temperature, followed by a 30-min wash to allow indicator deesterification. Smooth muscle cells were imaged with the use of a Noran Oz laser scanning confocal microscope (Noran Instruments, Middleton, WI) and a ×60 water immersion objective (1.2 numerical aperture) attached to a Nikon TE300 microscope. Fluo-4 was excited by using the 488 nm line of a krypton-argon laser, and emitted light >500 nm was captured. Images (56.3 × 52.8 μm) were recorded every 8.3 ms (120 images/s). The laser intensity used did not alter transient KCa current frequency or amplitude. Current and fluorescence measurements were synchronized by using a light-emitting diode placed above the recording chamber that was triggered during acquisition. Each cell was imaged for 15 s. Ca2+ sparks in smooth muscle cells were analyzed with the use of software kindly provided by Dr. M. T. Nelson (University of Vermont). Detection of Ca2+ sparks was performed by dividing an area 1.54 μm (7 pixels) × 1.54 μm (7 pixels) (i.e., 2.37 μm2) in each image (F) by a baseline (F0) that was determined by averaging 10 images without Ca2+ spark activity. The entire area of each image was analyzed to detect Ca2+ sparks. A Ca2+ spark was defined as a local increase in F/F0 that was >1.2.

Fura-2 imaging

Cerebral arteries were incubated with the ratio-metric fluorescent Ca2+ indicator fura-2 AM (5 μM) and 0.05% pluronic F-127 for 20 min, followed by a 15-min wash. All experiments were performed using solution B (composition described in Patch-clamp electrophysiology). Fura-2 was alternately excited at 340 or 380 nm using a PC-driven hyperswitch (Ionoptix, Milton, MA). Background corrected ratios were collected every 1 s at 510 nm using a photomultiplier tube (Ionoptix). SR Ca2+ load ([Ca2+]SR) was estimated by rapidly applying a high concentration of caffeine (10 mM), an RyR channel activator, and measuring the amplitude of [Ca2+]i transients (i.e., Δ[Ca2+]i). Intracellular Ca2+ concentrations were calculated by using the following equation (12):

where R is the 340/380 nm ratio; Rmin and Rmax are the minimum and maximum ratios determined in Ca2+-free and saturating Ca2+ solutions, respectively, Sf2/Sb2 is the ratio of Ca2+-free to Ca2+-replete emissions at 380 nm excitation, and Kd is the dissociation constant for fura-2 (282 nM) (19). Rmin, Rmax, Sf2, and Sb2 were determined at the end of experiments and in separate experiments by increasing the Ca2+ permeability of smooth muscle cells with ionomycin (10 μM) and by perfusing cells with a high-Ca2+ (10 mM) or Ca2+-free (no added Ca2+, 5 mM EGTA) solution.

Measurement of cellular dimensions

Isolated smooth muscle cells were allowed to settle on a glass coverslip in a chamber with Ca2+-free, HEPES-containing patch-clamp bath solution (composition described in Patch-clamp electrophysiology). Cell images were acquired with the use of a Zeiss LSM5 confocal microscope. Cell length and width were calculated using Pascal software (Zeiss).

Statistics

Values are expressed as means ± SE. Student's t-test and Student-Newman-Keuls test were used for comparing paired or unpaired data and multiple data sets, respectively. Simultaneous Ca2+ spark and transient KCa current amplitude data were fit with a linear regression function, and the slope ± SE of each fit was compared using Student's t-test and Graphpad Prizm (San Diego, CA). P < 0.05 was considered significant.

RESULTS

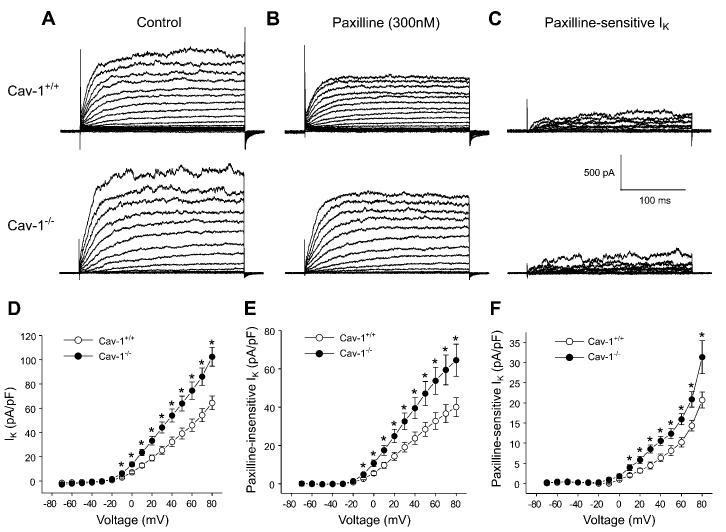

Caveolae are absent in cerebral artery smooth muscle cells of cav-1−/− mice

Electron microscopy revealed that abundant caveolae were present in the sarcolemma of smooth muscle cells of small-diameter (∼150 μm) cerebral arteries of cav-1+/+ mice (Fig. 1, A and B). In contrast, caveolae were not observed in cerebral artery smooth muscle cells of cav-1−/− mice (Fig. 1, C and D). These data indicate that cav-1 is necessary for caveolae formation in smooth muscle cells of small cerebral arteries.

Fig. 1.

Genetic ablation of caveolin-1 (cav-1) abolishes caveolae in cerebral artery smooth muscle cells. A: electron micrograph illustrates sarcolemma of smooth muscle cell in cerebral artery from cav-1+/+ mouse. Abundant caveolae are present within sarcolemma. B: magnification of area illustrated by black box in A showing caveolae. C: caveolae were absent in sarcolemma of cav-1−/− cerebral artery smooth muscle cells. D: magnification of area highlighted by black box in C.

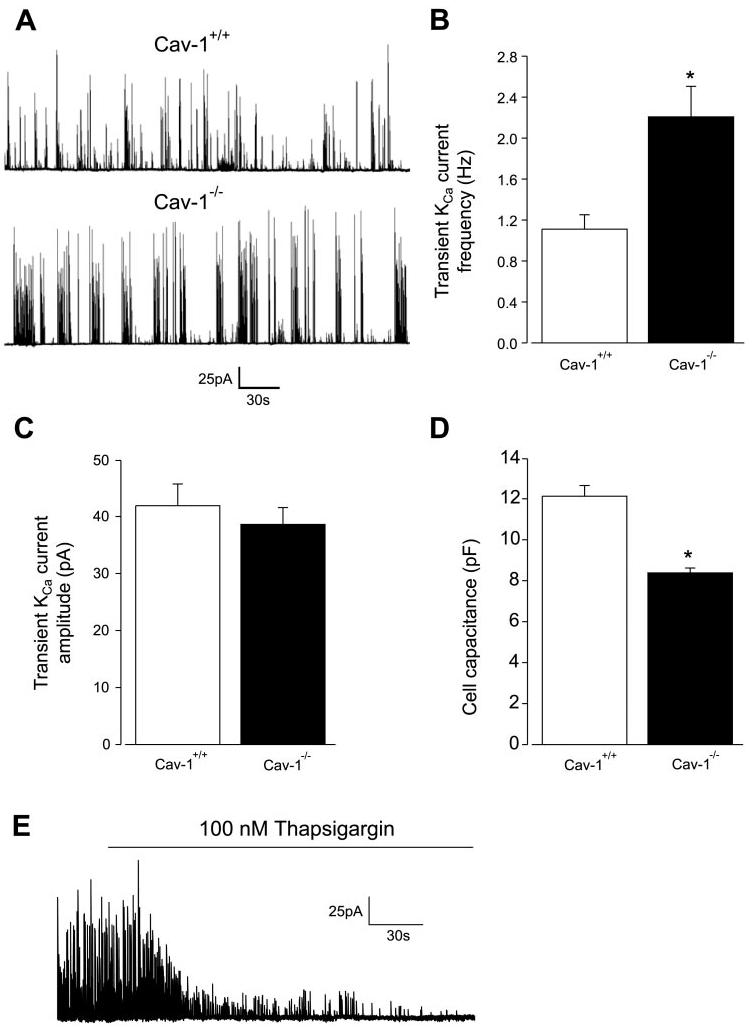

Transient KCa current frequency is higher in cav-1−/− than in cav-1+/+ cerebral artery smooth muscle cells

To investigate the effects of cav-1 ablation on Ca2+ spark-to-KCa channel signaling, transient KCa currents were measured in cerebral artery smooth muscle cells of cav-1+/+ and cav-1−/− mice. Transient KCa currents were measured at −40 mV, which is the membrane potential of cerebral arteries pressurized to 60 mmHg (19). Mean transient KCa current frequency was 1.11 ± 0.14 Hz in cav-1+/+ cells (n = 35) and 2.20 ± 0.30 Hz in cav-1−/− cells (n = 31), or approximately twofold higher (Fig. 2, A and B). In contrast, transient KCa current amplitude was similar in cav-1+/+ and cav-1−/− cells (Fig. 2, A and C).

Fig. 2.

Cav-1 ablation elevates transient large-conductance Ca2+-activated potassium (KCa) current frequency in cerebral artery smooth muscle cells. A: original traces illustrate transient KCa currents in a cav-1+/+ (top) and cav-1−/− (bottom) cell at −40 mV. B: mean transient KCa current frequency was higher in cav-1−/− (n = 31) when compared with cav-1+/+ (n = 35) cells. C: mean transient KCa current amplitude was similar in cav-1+/+ (n = 35) and cav-1−/− (n = 31) cells. D: mean cell capacitance of cav-1−/− cells (n = 49) was smaller than for cav-1+/+ cells (n = 55). E: thapsigargin (100 nM) abolishes transient KCa currents in a cav-1−/− cell voltage-clamped at −40 mV. Similar results were obtained in 4 cells. *P < 0.05 when compared with cav-1+/+ cells.

Cell capacitance of cav-1−/− cells (∼8.4 pF) was smaller than for cav-1+/+ cells (∼12.1 pF; Fig. 2D). To investigate whether cell size underlies the difference in cav-1+/+ and cav-1−/− cell capacitance, cellular dimensions were measured. Cells were observed in a Ca2+-free bath solution to induce maximal relaxation. Cav-1+/+ and cav-1−/− cell length [in μm: cav-1+/+, 37.1 ± 1.6 (n = 32); cav-1−/−, 39.4 ± 2.6 (n = 33)] and width [in μm: cav-1+/+, 9.6 ± 0.3 (n = 32); cav-1−/−, 9.4 ± 0.3 (n = 33)] were not different (P > 0.05 for each). These data suggest that cav-1 ablation reduces the cell surface area but does not alter the dimensions of cerebral artery smooth muscle cells.

In arterial smooth muscle cells, transient KCa currents occur due to SR Ca2+ release (38). We sought to determine mechanisms that activate transient KCa currents in cav-1−/− cells. In cav-1−/− cells, thapsigargin (100 nM), an SR Ca2+ ATPase inhibitor, abolished transient KCa currents, indicating that these events occur due to SR Ca2+ release (Fig. 2E; n = 4).

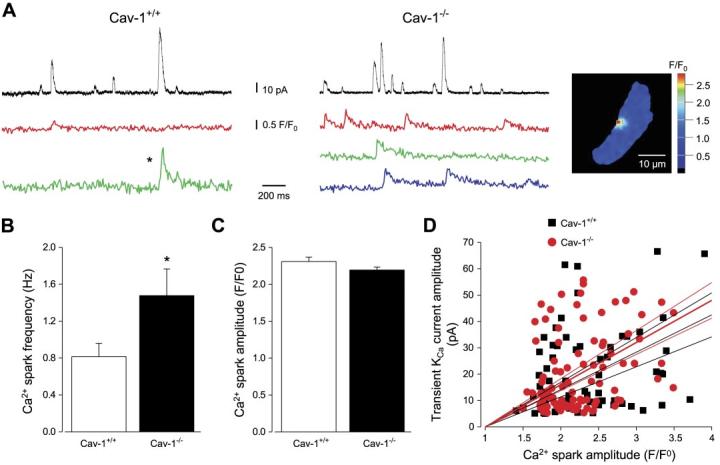

Ca2+ spark frequency is elevated in cav-1−/− cells when compared with cav-1+/+ cells, but the amplitude relationship between Ca2+ sparks and transient KCa currents is similar

Elevated transient KCa current frequency in cav-1−/− cells could occur because of an increase in Ca2+ spark frequency or an increase in the percentage of Ca2+ sparks that activate a transient KCa current (i.e., percent coupling). To investigate these possibilities and to compare Ca2+ spark properties in cav-1+/+ and cav-1−/− cells, simultaneous measurements of Ca2+ sparks and evoked transient KCa currents were obtained by performing confocal Ca2+ imaging in combination with patch-clamp electrophysiology.

At −40 mV, Ca2+ spark frequency was ∼1.8-fold higher in cav-1−/− cells than in cav-1+/+ cells (Fig. 3, A and B). In contrast, Ca2+ spark amplitude (Fig. 3C) and spatial spread [full width at half-maximal amplitude; cav-1+/+, 1.82 ± 0.13 μm (n = 40); cav-1−/−, 1.94 ± 0.11 μm (n = 59)] were similar in cav-1+/+ and cav-1−/− cells (P > 0.05 for each). The percentage of Ca2+ sparks that activated a transient KCa current (cav-1+/+, 67 ± 8%; cav-1−/−, 71 ± 4%) and the amplitude relationship between Ca2+ sparks and transient KCa currents were also similar (Fig. 3, A and D). Taken together, these data indicate that genetic ablation of cav-1−/− elevates Ca2+ spark frequency, leading to an increase in transient KCa current frequency.

Fig. 3.

Ca2+ spark frequency is higher in cav-1−/− cells than in cav-1+/+ cells. A: simultaneous measurements of Ca2+ sparks (bottom colored traces) and transient KCa currents (top black traces) at −40 mV in a cav-1+/+ cell (left) and cav-1−/− cell (right). Inset: peak of Ca2+ spark, labeled by asterisk in A, with yellow box in image indicating region from where F/F0 trace was obtained. B: mean Ca2+ spark frequency in cav-1+/+ (n = 9) and cav-1−/− (n = 7) cells. C: mean Ca2+ spark amplitude in cav-1+/+ (n = 88) and cav-1−/− (n = 124) cells. D: amplitude correlation of Ca2+ sparks and evoked transient KCa currents in cav-1+/+ (black squares) and cav-1−/− cells (red circles) with linear fit and 95% confidence bands to each data set [slope ± SE: cav-1+/+, 14.2 ± 1.4 (r = 0.25, n = 62, P < 0.0001); cav-1−/−, 16.0 ± 1.1 (r = 0.32, n = 91, P = 0.01)]. Amplitude relationship was not significantly different in cav-1+/+ and cav-1−/− cells (P > 0.05). *P < 0.05 when compared with cav-1+/+ cells.

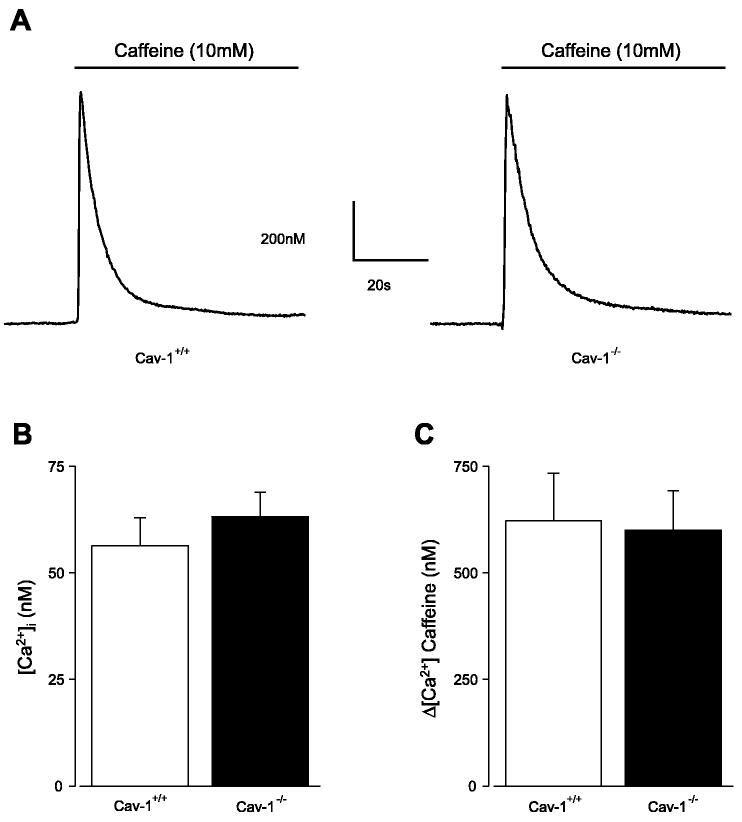

Cytosolic [Ca2+]i and [Ca2+]SR are similar in cav-1+/+ and cav-1−/− cells

Cytosolic [Ca2+]i and [Ca2+]SR regulate Ca2+ sparks in arterial smooth muscle cells (6, 38). However, [Ca2+]i and [Ca2+]SR, as determined by caffeine (10 mM)-induced Ca2+ transients, were not different in cav-1+/+ and cav-1−/− cerebral arteries (Fig. 4, A–C). Thus the higher Ca2+ spark frequency in cav-1−/− cells is not because of elevated cytosolic or SR Ca2+ concentration.

Fig. 4.

Intracellular Ca2+ concentration ([Ca2+]i) and sarcoplasmic reticulum Ca2+ load are similar in cav-1+/+ and cav-1−/− cerebral arteries. A: [Ca2+]i and caffeine (10 mM)-induced Ca2+ transients were measured in cav-1+/+ and cav-1−/− cerebral arteries using fura-2. B: [Ca2+]i was similar in cav-1+/+ (n = 7) and cav-1−/− (n = 9) cerebral arteries. C: caffeine-induced Ca2+ transients were similar in cav-1+/+ (n = 7) and cav-1−/− (n = 9).

Nω-nitro-l-arginine does not inhibit transient KCa currents in cav-1+/+ or cav-1−/− cells

Cav-1 ablation leads to nitric oxide (NO) synthase (NOS) activation and an increase in NO generation (10, 34). NO donors activate Ca2+ sparks in arterial smooth muscle cells (31). Therefore, we investigated whether Ca2+ spark frequency is higher in cav-1−/− cells because of elevated NOS activity. Nω-nitro-l-arginine (1 mM), a NOS blocker, did not alter transient KCa current frequency or amplitude in either cav-1+/+ [%control; frequency, 122 ± 16; amplitude, 107 ± 21 (n = 6)] or cav-1−/− [frequency, 106 ± 13; amplitude, 90 ± 17 (n = 5)] cells (P > 0.05 for each). These data suggest that the Ca2+ spark frequency elevation in cav-1−/− cells does not occur through NOS activation.

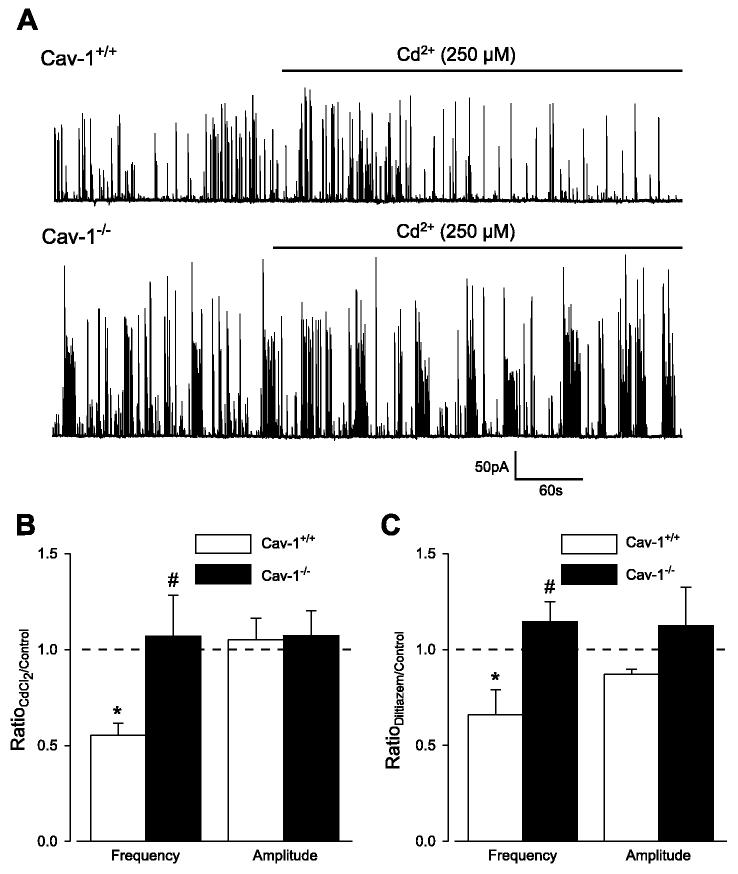

Transient KCa current regulation by voltage-dependent Ca2+ channels is abolished in cav-1−/− cells

In smooth muscle cells, Ca2+ sparks are activated by Ca2+ entering through sarcolemma voltage-dependent Ca2+ channels (14, 16, 20). We investigated whether Ca2+ sparks are more frequent in cav-1−/− cells because of enhanced coupling between voltage-dependent Ca2+ channels and RyR channels. In cav-1+/+ cells, Cd2+ (250 μM), a voltage-dependent Ca2+ channel blocker, or diltiazem (50 μM), an L-type Ca2+ channel blocker, reduced transient KCa current frequency to ∼51 and ∼57% of control, respectively, but did not alter transient KCa current amplitude (Fig. 5, A–C). In contrast, Cd2+ and diltiazem did not alter transient KCa current frequency or amplitude in cav-1−/− cells (Fig. 5, A–C). Thus Ca2+ spark regulation by voltage-dependent Ca2+ channels is abolished in cav-1−/− cells, indicating that higher Ca2+ spark frequency is not through enhanced coupling between voltage-dependent Ca2+ channels and RyR channels.

Fig. 5.

Voltage-dependent Ca2+ channel blockers reduce transient KCa current frequency in cav-1+/+ cells but not in cav-1−/− cells. A: original traces illustrating effect of CdCl2 (250 μM) on transient KCa currents in a cav-1+/+ and cav-1−/− cell at −40 mV. B: mean effects of CdCl2 on transient KCa current frequency and amplitude in cav-1+/+ (n = 5) and cav-1−/− (n = 6) cells. C: mean effect of diltiazem (50 μM) on transient KCa currents in cav-1+/+ (n = 5) and cav-1−/− (n = 4) cells. *P < 0.05 when compared with control obtained in same cells before Cd2+ or diltiazem application; #P < 0.05 when compared with cav-1+/+ cells.

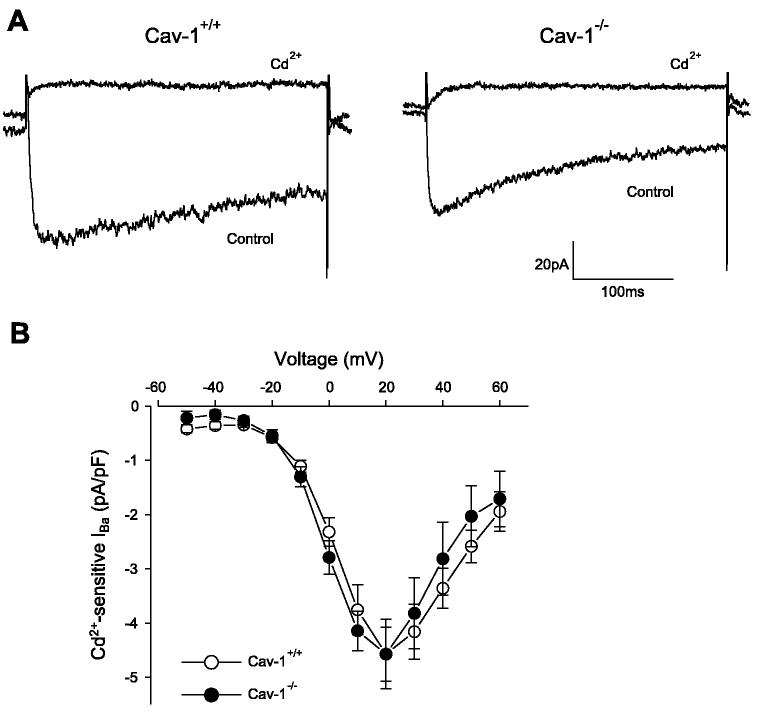

Voltage-dependent Ba2+ current density is similar in cav-1+/+ and cav-1−/− cells

In cav-1−/− cells, voltage-dependent Ca2+ channel density may be reduced or voltage-dependent Ca2+ channels may be insensitive to blockers. To test these hypotheses, voltage-dependent Ca2+ current density relationships were compared in cav-1+/+ and cav-1−/− cells using Ba2+ as the charge carrier. Voltage-dependent Ba2+ current density was similar, and Cd2+ abolished voltage-dependent Ba2+ currents in both cav-1+/+ and cav-1−/− cells (Fig. 6, A and B). Thus the absence of Ca2+ spark regulation by voltage-dependent Ca2+ entry in cav-1−/− cells cannot be explained by alterations in sarcolemma voltage-dependent Ca2+ current density or Cd2+ sensitivity.

Fig. 6.

Voltage-dependent Ca2+ current density is similar in cav-1+/+ and cav-1−/− cells. A: original traces illustrating voltage-dependent Ba2+ currents (IBa) elicited by a voltage step from a holding potential of −80 to +20 mV in cav-1+/+ and cav-1−/− cerebral artery smooth muscle cells. CdCl2 (250 μM) abolished (IBa) in cav-1+/+ and cav-1−/− cells. B: current density-voltage relationship of CdCl2 (250 μM)-sensitive currents in cav-1+/+ (n = 9) and cav-1−/− (n = 9) cells. P > 0.05 for each voltage when compared with cav-1+/+.

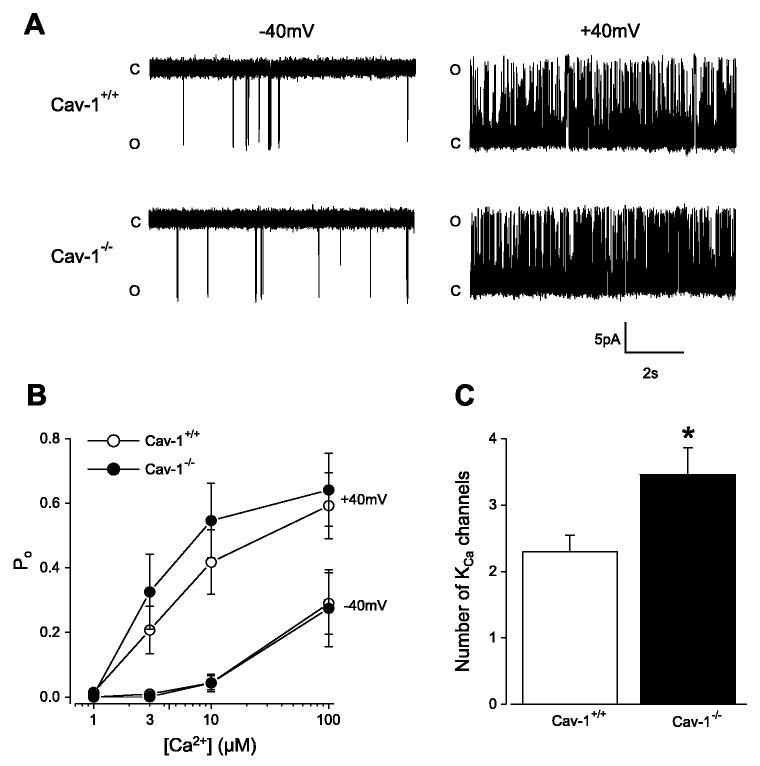

KCa and KV current density is higher in cav-1−/− than in cav-1+/+ cells

In cardiac myocytes, coupling between voltage-gated Ca2+ channels and RyR channels is tight, whereas in smooth muscle cells, this communication is loose (5, 20, 24, 36). Conceivably, Ca2+ spark regulation by voltage-dependent Ca2+ channels may be abolished in cav-1−/− cells because of an increase in the distance between the sarcolemma and the SR. Therefore, we sought to study the distance between Ca2+ spark sites and a sarcolemmal Ca2+ spark target in cav-1+/+ and cav-1−/− cells. To do this, KCa channel properties were measured, thereby allowing further investigation of Ca2+ spark to KCa channel coupling.

Transient KCa current amplitude is dependent on KCa channel conductance and Ca2+ sensitivity (4). In excised inside-out patches, single KCa channel slope conductance between −40 and +40 mV [cav-1+/+, 268 ± 3 pS(n = 9); cav-1−/−, 260 ± 3 pS (n = 7); P > 0.05] and KCa channel-apparent Ca2+ sensitivity were similar in cav-1+/+ and cav-1−/− cells (Fig. 7, A and B). Transient KCa current amplitude also depends on the number of KCa channels activated by a Ca2+ spark. On average, inside-out patches pulled from cav-1−/− cells contained ∼1.5-fold more KCa channels than patches obtained from cav-1+/+ cells (Fig. 7C). This finding was not due to differences in the size of patch pipettes used for these experiments [cav-1+/+, 28.6 ± 1.2 MΩ (n = 17); cav-1−/−, 27.1 ± 0.7 MΩ (n = 22); P > 0.05]. These data suggest that sarcolemma KCa channel density is higher in cav-1−/− cells than in cav-1+/+ cells.

Fig. 7.

Single KCa channel properties in cav-1+/+ and cav-1−/− cells. A: original records illustrate single KCa channel openings in 10 μM Ca2+ at −40 and +40 mV in inside-out patches from a cav-1+/+ and cav-1−/− cell. B: at −40 and +40 mV, apparent Ca2+ sensitivity of KCa channels was similar for cav-1+/+ (n = 8–9 for each [Ca2+]) and cav-1−/− (n = 7 for each [Ca2+]) cells (P > 0.05 for each). Po, open probability. C: inside-out patches from cav-1−/− cells (n = 22) contained more KCa channels than patches from cav-1+/+ cells (n = 17). C, closed; O, open. *P < 0.05.

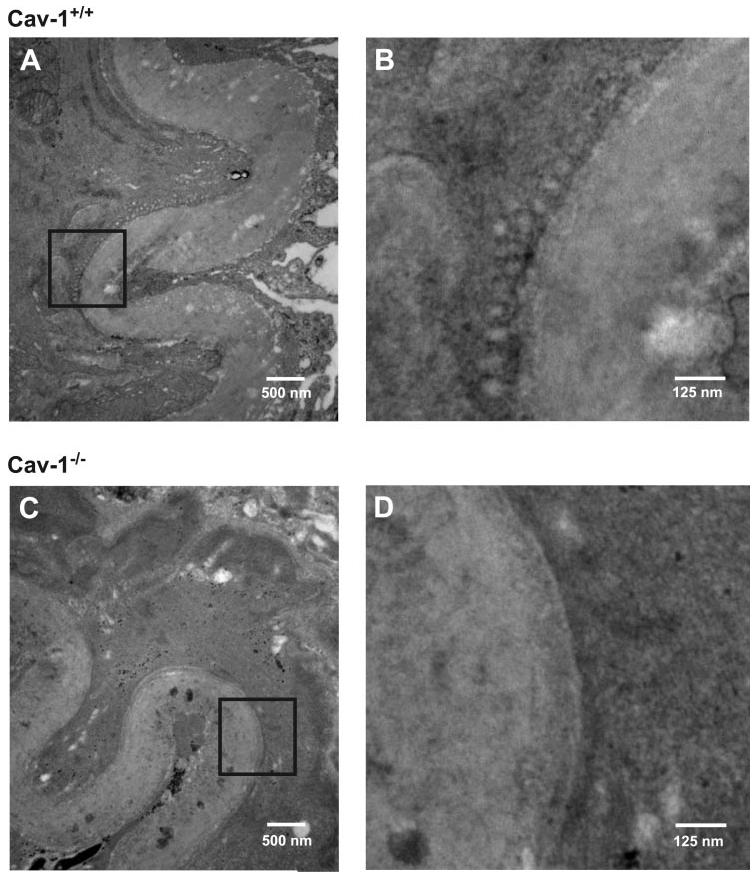

To further examine KCa channel properties, whole cell K+ current density was measured in cav-1+/+ and cav-1−/− cells. K+ currents were measured by using a strongly buffered Ca2+-free pipette solution to abolish Ca2+-dependent KCa channel activation. Whole cell K+ current density was larger in cav-1−/− cells than in cav-1+/+ cells (Fig. 8, A and D). Paxilline (300 nM), a selective KCa channel blocker (21, 35), partially inhibited K+ currents in both cav-1+/+ and cav-1−/− cells (Fig. 8B). Paxilline-insensitive current density, which arises because of KV channel activation, was larger in cav-1−/− cells than in cav-1+/+ cells (Fig. 8, B and E). Similarly, paxilline-sensitive current density, which occurs through KCa channel activation, was larger in cav-1−/− cells than in cav-1+/+ cells (Fig. 8, C and F). These data suggest that cav-1 ablation elevates the sarcolemmal current density of both KCa and KV channels.

Fig. 8.

Whole cell K+, KCa, and KV current density is elevated in cav-1−/− cells. A: original recordings of whole cell K+ currents activated by depolarizing voltage steps in a cav-1+/+ and cav-1−/− cell. B: paxilline (300 nM) inhibits K+ currents in the same cells illustrated in A. C: paxilline-sensitive K+ currents. D: mean whole cell K+ current density (pA/pF) in cav-1+/+ (n = 11) and cav-1−/− (n = 9) cells. E: paxilline-insensitive K+ current density. F: paxilline-sensitive K+ current density. *P < 0.05 when compared with cav-1+/+ cells.

DISCUSSION

The impact of cav-1 ablation on the regulation of Ca2+ sparks by voltage-dependent Ca2+ channels and the communication between Ca2+ sparks and KCa channels were investigated in arterial smooth muscle cells. Caveolae were not observed in cav-1−/− cerebral artery smooth muscle cells, consistent with a role for this protein in caveolae formation (10, 34, 39). Cav-1 ablation attenuated coupling between voltage-dependent Ca2+ channels and RyR channels that generate Ca2+ sparks. Cav-1 ablation also elevated Ca2+ spark frequency, although this was not due to an increase in voltage-dependent Ca2+ current density, cytosolic or SR Ca2+ concentration, or NOS activity. Although there was an increase in KCa channel density in cav-1−/− cells, transient KCa current amplitude was similar to that in cav-1+/+ cells. Taken together, the data suggest that cav-1 abolishment leads to uncoupling between voltage-dependent Ca2+ channels and RyR channels that generate Ca2+ sparks but does not alter transient KCa current activation by Ca2+ sparks.

In smooth muscle cells, coupling between voltage-dependent Ca2+ channels and RyR channels is “loos” (20). Although structural and molecular mechanisms that establish this coupling process are unclear, loss of voltage-dependent Ca2+ channel to RyR channel communication in cav-1−/− cells likely occurs because of spatial separation of these proteins. Supporting this hypothesis is evidence that although voltage-dependent Ca2+ current density was similar in cav-1+/+ and cav-1−/− cells, regulation of transient KCa currents by voltage-dependent Ca2+ channel blockers was abolished in cav-1−/− cells. In addition, although KCa channel density was elevated in cav-1−/− cells, mean transient KCa current amplitude was similar to that in cav-1+/+ cells. KCa channel conductance, Ca2+ spark amplitude and spatial spread, the effective coupling of Ca2+ sparks to KCa channels, and KCa channel-apparent Ca2+ sensitivity were similar in cav-1+/+ and cav-1−/− cells. Caveolae are structural membrane invaginations that may reduce the sarcolemma to SR distance and physically localize RyR channels nearby voltage-dependent Ca2+ channels and KCa channels in cav-1+/+ cells. A flattening of the sarcolemma in cav-1−/− cells may explain the proposed increase in the signaling distance between RyR channels and voltage-dependent Ca2+ channels and KCa channels. In cav-1−/− cells, a distant spark would impact a smaller membrane area and induce a lower subsarcolemmal [Ca2+]i elevation. Consistent with our observations, higher KCa channel density would be required for distant Ca2+ sparks to activate transient KCa currents of similar amplitude to those in cav-1+/+ cells.

Another explanation for the proposed increase in signaling distance is that cav-1 abolishment leads to delocalization of voltage-dependent Ca2+ channels and KCa channels from within the vicinity of the spark site. Several lines of evidence support such a proposal. In smooth muscle cells, caveolae compartmentalize voltage-dependent Ca2+ channels and KCa channels (3, 8). In arterial smooth muscle cells, KCa channels are proposed not to cluster above Ca2+ sparks sites, although in Bufo marinus stomach smooth muscle cells, such clustering may occur (30, 42). In guinea pig bladder smooth muscle, peripheral SR and caveolae are in close proximity, and L-type Ca2+ channels located in caveolae strips may be closely opposed to SR RyR channels (25). It is not clear what causes the elevation in KCa channel density in cav-1−/− cells, but in cultured human myometrial smooth muscle cells, KCa channels associate with caveolins 1 and 2, and cholesterol depletion with cyclodextrin leads to an increase in whole cell KCa current density (3), consistent with the results here. Furthermore, in bovine endothelial cells, cav-1 physically interacts with and inhibits KCa channels and this effect can be removed by cholesterol depletion, leading to channel activation (37).

Investigating the effects of chronic caveolae deficiency on smooth muscle Ca2+ signaling can provide insights into physiological regulation by these membrane organelles in cav-1+/+ cells and potential changes that occur during pathophysiology and ontogeny (11, 29, 32, 34, 39). In contrast to the observations here, acute cholesterol depletion with dextrin inhibited arterial smooth muscle Ca2+ sparks (23). Acute cholesterol depletion and chronic cav-1 ablation may differentially regulate Ca2+ spark frequency through opposing effects on signaling pathways that regulate these events, and in the case of the genetic model, through developmental changes that occur in the sustained absence of cav-1 (10, 39). However, dextrin treatment also induces a change in membrane fluidity that may inhibit Ca2+ sparks (26). In agreement, both dextrin and cav-1 ablation abolished coupling between voltage-dependent Ca2+ channels and RyR channels that generate sparks (present data and Ref. 23). Whereas dextrin treatment disrupts both caveolar and noncaveolar lipid rafts, in the absence of cav-1, noncaveolar lipid rafts would remain (see Ref. 40). Thus our data suggest that caveolae-localized voltage-dependent Ca2+ channels regulate Ca2+ sparks in arterial smooth muscle cells. In another previous study, transient KCa current frequency was reduced in arterial smooth muscle cells of cav-1−/− mice (10). It is unclear why data here are contradictory to those observations, but in the previous study, effects of cav-1 deficiency on Ca2+ sparks were not measured (10).

Through its amino-terminal scaffolding domain, cav-1 inhibits the activity of many binding partners, including NOS, protein kinase C, and adenylyl cyclase (28, 34). Cav-1 is found in the cytosol (22) and, conceivably, may interact with and inhibit RyR channels. Cav-1 is also found in mitochondria, which regulate Ca2+ sparks in cerebral artery smooth muscle cells (7, 41). Cav-1 abolishment may also activate RyR channels indirectly by modulating the activity of signaling pathways that regulate Ca2+ sparks (e.g., see Refs. 15 and 41). Data here indicate that cav-1 ablation does not activate Ca2+ sparks through NOS activation (31, 33). Because cav-1 ablation may activate RyR channels directly and indirectly, future studies will be required to determine the specific underlying mechanisms. The physiological impact of the transient KCa current frequency elevation in cav-1−/− cells would be a membrane hyperpolarization that reduces voltage-dependent Ca2+ channel activity, leading to a decrease in global [Ca2+]i and vasodilation (15). Cav-1−/− aortas contract less in response to vasoconstrictors and relax more in response to acetylcholine, a vasodilator, when compared with cav-1+/+ arteries (10, 33), supporting upregulation of a vasodilatory pathway.

In summary, data show that genetic ablation of cav-1 leads to loss of caveolae, an increase in Ca2+ spark frequency, abolishment of Ca2+ spark regulation by voltage-dependent Ca2+ channels, and an increase in KCa channel density in cerebral artery smooth muscle cells. In contrast, cav-1 ablation does not attenuate transient KCa current activation by Ca2+ sparks.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Dr. A. Ahmed for technical assistance with electron microscopy and Dr. R. Ostrom for helpful comments on the manuscript. X. Cheng is a recipient of a Predoctoral Fellowship from the Southeast Affiliate of the American Heart Association.

Footnotes

The costs of publication of this article were defrayed in part by the payment of page charges. The article must therefore be hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 U.S.C. Section 1734 solely to indicate this fact.

GRANTS

This study was supported by grants from National Institutes of Health and American Heart Association National Center (to J. H. Jaggar).

REFERENCES

- 1.Babiychuk EB, Smith RD, Burdyga T, Babiychuk VS, Wray S, Draeger A. Membrane cholesterol regulates smooth muscle phasic contraction. J Membr Biol. 2004;198:95–101. doi: 10.1007/s00232-004-0663-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Berridge MJ, Lipp P, Bootman MD. The versatility and universality of calcium signalling. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2000;1:11–21. doi: 10.1038/35036035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Brainard AM, Miller AJ, Martens JR, England SK. Maxi-K channels localize to caveolae in human myometrium: a role for an actin-channel-caveolin complex in the regulation of myometrial smooth muscle K+ current. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2005;289:C49–C57. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00399.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Brenner R, Perez GJ, Bonev AD, Eckman DM, Kosek JC, Wiler SW, Patterson AJ, Nelson MT, Aldrich RW. Vasoregulation by the β1 subunit of the calcium-activated potassium channel. Nature. 2000;407:870–876. doi: 10.1038/35038011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cannell MB, Cheng H, Lederer WJ. The control of calcium release in heart muscle. Science. 1995;268:1045–1049. doi: 10.1126/science.7754384. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cheranov SY, Jaggar JH. Sarcoplasmic reticulum calcium load regulates rat arterial smooth muscle calcium sparks and transient KCa currents. J Physiol. 2002;544:71–84. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2002.025197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cheranov SY, Jaggar JH. Mitochondrial modulation of Ca2+ sparks and transient KCa currents in smooth muscle cells of rat cerebral arteries. J Physiol. 2004;556:755–771. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2003.059568. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Darby PJ, Kwan CY, Daniel EE. Caveolae from canine airway smooth muscle contain the necessary components for a role in Ca2+ handling. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2000;279:L1226–L1235. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.2000.279.6.L1226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Doyle DD, Upshaw-Earley J, Bell E, Palfrey HC. Expression of caveolin-3 in rat aortic vascular smooth muscle cells is determined by developmental state. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2003;304:22–25. doi: 10.1016/s0006-291x(03)00528-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Drab M, Verkade P, Elger M, Kasper M, Lohn M, Lauterbach B, Menne J, Lindschau C, Mende F, Luft FC, Schedl A, Haller H, Kurzchalia TV. Loss of caveolae, vascular dysfunction, and pulmonary defects in caveolin-1 gene-disrupted mice. Science. 2001;293:2449–2452. doi: 10.1126/science.1062688. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gratton JP, Bernatchez P, Sessa WC. Caveolae and caveolins in the cardiovascular system. Circ Res. 2004;94:1408–1417. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000129178.56294.17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Grynkiewicz G, Poenie M, Tsien RY. A new generation of Ca2+ indicators with greatly improved fluorescence properties. J Biol Chem. 1985;260:3440–3450. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Isshiki M, Anderson RG. Function of caveolae in Ca2+ entry and Ca2+-dependent signal transduction. Traffic. 2003;4:717–723. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0854.2003.00130.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jaggar JH. Intravascular pressure regulates local and global Ca2+ signaling in cerebral artery smooth muscle cells. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2001;281:C439–C448. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.2001.281.2.C439. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jaggar JH, Porter VA, Lederer WJ, Nelson MT. Calcium sparks in smooth muscle. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2000;278:C235–C256. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.2000.278.2.C235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jaggar JH, Stevenson AS, Nelson MT. Voltage dependence of Ca2+ sparks in intact cerebral arteries. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 1998;274:C1755–C1761. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.1998.274.6.C1755. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Jaggar JH, Wellman GC, Heppner TJ, Porter VA, Perez GJ, Gollasch M, Kleppisch T, Rubart M, Stevenson AS, Lederer WJ, Knot HJ, Bonev AD, Nelson MT. Ca2+ channels, ryanodine receptors and Ca2+-activated K+ channels: a functional unit for regulating arterial tone. Acta Physiol Scand. 1998;164:577–587. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-201X.1998.00462.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Je HD, Gallant C, Leavis PC, Morgan KG. Caveolin-1 regulates contractility in differentiated vascular smooth muscle. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2004;286:H91–H98. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00472.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Knot HJ, Nelson MT. Regulation of arterial diameter and wall [Ca2+] in cerebral arteries of rat by membrane potential and intravascular pressure. J Physiol. 1998;508:199–209. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.1998.199br.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kotlikoff MI. Calcium-induced calcium release in smooth muscle: the case for loose coupling. Prog Biophys Mol Biol. 2003;83:171–191. doi: 10.1016/s0079-6107(03)00056-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Li G, Cheung DW. Effects of paxilline on K+ channels in rat mesenteric arterial cells. Eur J Pharmacol. 1999;372:103–107. doi: 10.1016/s0014-2999(99)00188-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Li WP, Liu P, Pilcher BK, Anderson RG. Cell-specific targeting of caveolin-1 to caveolae, secretory vesicles, cytoplasm or mitochondria. J Cell Sci. 2001;114:1397–1408. doi: 10.1242/jcs.114.7.1397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lohn M, Furstenau M, Sagach V, Elger M, Schulze W, Luft FC, Haller H, Gollasch M. Ignition of calcium sparks in arterial and cardiac muscle through caveolae. Circ Res. 2000;87:1034–1039. doi: 10.1161/01.res.87.11.1034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lopez-Lopez JR, Shacklock PS, Balke CW, Wier WG. Local calcium transients triggered by single L-type calcium channel currents in cardiac cells. Science. 1995;268:1042–1045. doi: 10.1126/science.7754383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Moore ED, Voigt T, Kobayashi YM, Isenberg G, Fay FS, Gallitelli MF, Franzini-Armstrong C. Organization of Ca2+ release units in excitable smooth muscle of the guinea-pig urinary bladder. Biophys J. 2004;87:1836–1847. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.104.044123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Munro S. Lipid rafts: elusive or illusive? Cell. 2003;115:377–388. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(03)00882-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Nelson MT, Cheng H, Rubart M, Santana LF, Bonev AD, Knot HJ, Lederer WJ. Relaxation of arterial smooth muscle by calcium sparks. Science. 1995;270:633–637. doi: 10.1126/science.270.5236.633. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ostrom RS, Liu X, Head BP, Gregorian C, Seasholtz TM, Insel PA. Localization of adenylyl cyclase isoforms and G protein-coupled receptors in vascular smooth muscle cells: expression in caveolin-rich and noncaveolin domains. Mol Pharmacol. 2002;62:983–992. doi: 10.1124/mol.62.5.983. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Park DS, Cohen AW, Frank PG, Razani B, Lee H, Williams TM, Chandra M, Shirani J, De Souza AP, Tang B, Jelicks LA, Factor SM, Weiss LM, Tanowitz HB, Lisanti MP. Caveolin-1 null (−/−) mice show dramatic reductions in life span. Biochemistry. 2003;42:15124–15131. doi: 10.1021/bi0356348. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Perez GJ, Bonev AD, Nelson MT. Micromolar Ca2+ from sparks activates Ca2+-sensitive K+ channels in rat cerebral artery smooth muscle. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2001;281:C1769–C1775. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.2001.281.6.C1769. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Porter VA, Bonev AD, Knot HJ, Heppner TJ, Stevenson AS, Kleppisch T, Lederer WJ, Nelson MT. Frequency modulation of Ca2+ sparks is involved in regulation of arterial diameter by cyclic nucleotides. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 1998;274:C1346–C1355. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.1998.274.5.C1346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ratajczak P, Damy T, Heymes C, Oliviero P, Marotte F, Robidel E, Sercombe R, Boczkowski J, Rappaport L, Samuel JL. Caveolin-1 and -3 dissociations from caveolae to cytosol in the heart during aging and after myocardial infarction in rat. Cardiovasc Res. 2003;57:358–369. doi: 10.1016/s0008-6363(02)00660-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Razani B, Engelman JA, Wang XB, Schubert W, Zhang XL, Marks CB, Macaluso F, Russell RG, Li M, Pestell RG, Di VD, Hou H, Jr, Kneitz B, Lagaud G, Christ GJ, Edelmann W, Lisanti MP. Caveolin-1 null mice are viable but show evidence of hyperproliferative and vascular abnormalities. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:38121–38138. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M105408200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Razani B, Woodman SE, Lisanti MP. Caveolae: from cell biology to animal physiology. Pharmacol Rev. 2002;54:431–467. doi: 10.1124/pr.54.3.431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sanchez M, McManus OB. Paxilline inhibition of the alpha-subunit of the high-conductance calcium-activated potassium channel. Neuropharmacology. 1996;35:963–968. doi: 10.1016/0028-3908(96)00137-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wang SQ, Song LS, Lakatta EG, Cheng H. Ca2+ signaling between single L-type Ca2+ channels and ryanodine receptors in heart cells. Nature. 2001;410:592–596. doi: 10.1038/35069083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wang XL, Ye D, Peterson TE, Cao S, Shah VH, Katusic ZS, Sieck GC, Lee HC. Caveolae targeting and regulation of large conductance Ca2+-activated K+ channels in vascular endothelial cells. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:11656–11664. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M410987200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wellman GC, Santana LF, Bonev AD, Nelson MT. Role of phospholamban in the modulation of arterial Ca2+ sparks and Ca2+-activated K+ channels by cAMP. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2001;281:C1029–C1037. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.2001.281.3.C1029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Williams TM, Lisanti MP. The caveolin genes: from cell biology to medicine. Ann Med. 2004;36:584–595. doi: 10.1080/07853890410018899. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Woodman SE, Park DS, Cohen AW, Cheung MW, Chandra M, Shirani J, Tang B, Jelicks LA, Kitsis RN, Christ GJ, Factor SM, Tanowitz HB, Lisanti MP. Caveolin-3 knock-out mice develop a progressive cardiomyopathy and show hyperactivation of the p42/44 MAPK cascade. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:38988–38997. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M205511200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Xi Q, Cheranov SY, Jaggar JH. Mitochondria-derived reactive oxygen species dilate cerebral arteries by activating Ca2+ sparks. Circ Res. 2005;97:354–362. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000177669.29525.78. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Zhuge R, Fogarty KE, Tuft RA, Walsh JV., Jr. Spontaneous transient outward currents arise from microdomains where BK channels are exposed to a mean Ca2+ concentration on the order of 10 μm during a Ca2+ spark. J Gen Physiol. 2002;120:15–27. doi: 10.1085/jgp.20028571. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]