Abstract

The genetic lesion in the quakingviable (qkv) mutant mice is a deletion 5′ to the qkI gene, resulting in severe hypomyelination. qkI produces several QKI protein isoforms via alternative splicing of the C-terminal coding exons. In the qkv/qkv brain, immunostaining of QKI proteins is diminished in an isoform-differential manner with undefined mechanisms. We examined the expression of QKI protein isoforms and qkI mRNA isoforms in the qkv/qkv mutants and the non-phenotypic wt/qkv littermates. Our results indicated significant reduction of all qkI mRNA isoforms in the central and peripheral nervous system during active myelination without detectable post-transcriptional abnormalities. In the early stage of myelin development, qkI mRNAs are differentially reduced, which appeared to be responsible for the reduction of the corresponding QKI protein isoforms. The reduced qkI expression was a specific consequence of the qkv lesion, not observed in other hypomyelination mutants. Further more, no abnormal qkI expression was found in testis, heart and astroglia of the qkv/qkv mice, suggesting that the reduction of qkI mRNAs occurred specifically in myelin-producing cells of the nervous system. These observations suggest that diminished qkI expression results from deletion of an enhancer that promotes qkI transcription specifically in myelinating glia during active myelinogenesis.

INTRODUCTION

Myelination, the ensheathment of neuronal axons by specialized membrane lamellae, is essential for the function and development of the nervous system. Oligodendrocytes and Schwann cells are responsible for myelinating the central and the peripheral nervous system (CNS and PNS), respectively. Quakingviable (qkv) is a well-known spontaneous mutation in mice that causes remarkable hypomyelination (1–3). The CNS of homozygous qkv mice is severely hypomyelinated whereas the PNS is only mildly affected (2,4). The homozygous qkv mice develop vigorous tremors from postnatal day 10 (P10). In contrast, the heterozygous littermates are non-phenotypic. The qkv hypomyelination is not due to reduced myelin-producing cells (5), but more likely due to deficits in cell development and myelin production. The genetic lesion is mapped 5′ to the qkI gene on chromosome 17, which encodes a selective RNA-binding protein QKI (6). Several QKI protein isoforms are derived from the qkI primary transcript via extensive alternative splicing of the C-terminal coding exons (6,7). The major QKI isoforms include QKI-5, QKI-6 and QKI-7; each harbors a single hnRNP K-homology (KH) RNA-binding domain (6). In the normal adult brain, QKI proteins are expressed in several types of glia but are absent in neurons (8). In the qkv/qkv mice, immunostaining of QKI is diminished specifically in oligodendrocytes and Schwann cells (8). Thus, the role of QKI has been implicated in controlling mRNA homeostasis during myelinogenesis, and the deficiency of QKI results in misregulation of its RNA targets, which in turn leads to hypomyelination (9). Indeed, QKI interacts with several mRNAs encoding major structural myelin proteins, and QKI deficiency is associated with post-transcriptional abnormalities at the levels of stability, localization and splicing of QKI-binding mRNAs in the qkv/qkv mice (10–12). These abnormalities suggest that QKI isoforms may play distinct roles at various steps of post-transcriptinal regulation.

Among the QKI isoforms, QKI-5 is expressed in many cell types during embryonic and neonatal development (6,8), shuttling between the cytoplasm and the nucleus (13). QKI-6 and QKI-7 are predominantly cytoplasmic, expressed at high levels in the brain during active myelinogenesis (8). In the qkv/qkv brain, QKI-6 and QKI-7 are undetectable in all oligodendrocytes, whereas the level of QKI-5 reduction geographically correlates with the severity of hypomyelination (8). How the qkv deletion leads to such a phenomenon remains unknown. In fact, the expression of qkI mRNA isoforms has not been adequately characterized in the qkv/qkv mice.

We have quantitatively analyzed the qkI mRNA isoforms and the QKI protein isoforms in the qkv/qkv mice and the wt/qkv non-phenotypic littermates. We found that all major qkI mRNA isoforms were significantly reduced in the developing brain, in the optic nerve and in the sciatic nerve of the qkv/qkv mice during the period of active myelinogenesis without detectable post-transcriptional deficits. Quantitative analysis further suggested that the reduction of qkI mRNA isoforms was responsible for the reduction of the corresponding QKI protein isoforms. In contrast, a normal level of qkI expression was observed in tissues outside of the nervous system and in the non-myelinating astroglia derived from the qkv/qkv mice. These results support the hypothesis that qkv may affect an enhancer required for elevated qkI transcription in myelin-producing cells during the period of active myelin production.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Animals and RNA preparation

Animals were treated according to NIH regulations under the approval of the Emory University IACUC. The qkv colony and the jpmsd colony (generously provided by Dr S. Billings-Gagliardi, University of Massachusetts, Worcester, MA, USA) were maintained at Emory animal facility as previously described (14). Various brain regions and nerves were dissected at ages indicated in the corresponding figure for total RNA extraction using Trizol™ according to the manufacturer’s protocol (Invitrogen). The quantity of RNA from each sample was determined by OD260 reading and further confirmed by ethidium bromide-stained agarose gel electrophoresis.

Cell culture

Primary astrocyte cultures were derived from individual brain stems of qkv/qkv and the wt/qkv non-phenotypic littermates at P2 following the well-established procedure (15). After 1 week in culture, the confluent glial cultures were shaken overnight at 300 r.p.m. in an incubator shaker (innova 4300, New Brunswick) at 37°C to remove oligodendrocytes. The astrocytes that remained attached were cultured for an additional day in fresh media before being subjected to RNA isolation. The genotype of each culture was determined by PCR of genomic DNA isolated from the cerebrum of each animal using the following primers: (i) gf1, the common 5′ primer detecting both wild-type and qkv allele: GGACTTCATTGCTGCAATTCGG; (ii) gr1, the common 3′ primer detecting both alleles: CGTTAATCCTCACCGCAGGTTC; (iii) df1, the 5′ primer detecting only the wild-type allele: GAACTACTATAGCCATTGTTGG. PCR was performed in the standard reaction buffer (Invitrogen) plus 4% DMSO for 35 cycles at 95°C for 20 s, 62°C for 30 s and 72°C for 1 min followed by ethidium bromide-stained agarose gel electrophoresis.

Immunoblot analysis and antibodies

Whole tissue lysate was prepared by sonication in 1× Laemmli buffer. The quantity of total protein in each sample was estimated by the Bradford assay (BioRad) before being subjected to SDS–PAGE. Cytoplasmic and nuclear extracts were derived from the C6 glioma cell line (ATCC) as described previously (16) followed by immunoblot analysis. Hybridization to the primary antibody was performed in PBS containing 0.2% Tween-20 and 1% milk. The monoclonal anti-myelin basic protein (anti-MBP) antibody was purchased from Chemicon (Temecula). The polyclonal antibody for QKI was generated by immunization of rabbit using recombinant QKI-7 produced in bacteria (Cocallico Inc.).

RNase protection assay (RPA) and RPA probes

The 3′ ends of the coding regions for qkI-5, qkI-6 and qkI-7 were RT–PCR amplified using mouse brain total RNA as template. Isoform-specific primers illustrated in Figure 3 are: (i) the common 5′ primer: CAACTGCCCAGGCTGCTC; (ii) the q7-specific 3′ primer: CTAGTCCTTCATCCAGCAAG; (iii) the q6-specific 3′ primer: GCCTATTAGCCTTTCGTTGGGAAAGC; (iv) the q5-specific 3′ primer: GCCTATTAGTTGCCGGTGGCGGCTCG. The cDNA fragment derived from RT–PCR was cloned into the TA-Cloning Vector (Invitrogen). The orientation of each cDNA insert was determined by sequencing, and the sequence was confirmed to be 100% identical to that previously published. Antisense riboprobes were generated by in vitro transcription in the presence of T7 polymerase (Stratagene) and 32P-UTP (Amersham) using linearized plasmids as DNA templates. The glyceraldehyde phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH) RPA probe was generated as previously described (10). The RPA was performed under conditions published in our previous report (10).

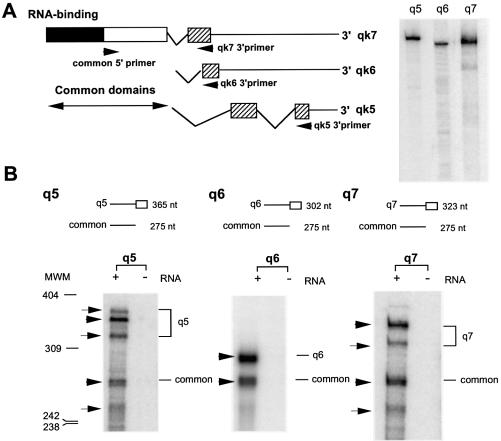

Figure 3.

RPA for detecting qkI mRNA isoforms. (A) Schematic representation of qkI mRNA isoforms illustrating the common 5′ domain and the alternative 3′ exons. The primers used in RT–PCR cloning of the 3′ coding region of each isoform are marked by arrowheads. The synthesis of full-length RPA probe is shown on the right. (B) RPA of total RNA isolated from wild-type mouse brain using the isoform-specific riboprobes. Each RPA is expected to generate an isoform-specific band and a common band for the rest of the isoforms. The size of predicted PRA products for each qkI isoform is illustrated on top of the corresponding panels, and marked by arrowheads in the corresponding RPA. Additional minor RPA products for qkI-5 and qkI-7 are marked by arrows, most likely representing undefined splicing junctions. MWM, molecular weight marker.

Sucrose gradient fractionation

Linear sucrose gradients (15–45%, w/v) were employed to fractionate cytoplasmic extracts derived from the brain stem of the qkv/qkv mutant and the wt/qkv non-phenotypic littermates using our published procedures (17). Each gradient was fractionated by upward replacement and collected into 12 fractions. Total RNA was isolated from each fraction by phenol/chloroform extraction followed by RPA to detect qkI mRNAs.

RNA-binding assay

RNA binding was carried out using previously published procedures (18). Briefly, 35S-labeled QKI isoforms were generated by in vitro translation using TNT containing T7 RNA polymerase (Promega) and incubated with biotinylated RNA encoding the 14 kDa MBP (M14). RNA-bound 35S-QKI isoforms were captured by streptavidin-conjugated Dyno beads. The RNA-binding activity of QKI was determined by scintillation counting.

RESULTS

All major QKI protein isoforms bind MBP mRNA and are reduced in the qkv/qkv brain

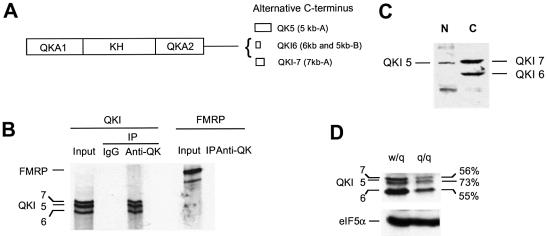

The three most abundant QKI protein isoforms in the brain are derived from four alternatively spliced mRNAs (Fig. 1A). QKI-5 is encoded by qk-5kb-A, QKI-6 is encoded by qk-6kb and qk-5kb-B, whereas QKI-7 is encoded by qk-7kb-A (7). These isoforms migrated on SDS–PAGE as a tight triplet (Fig. 1B, left). All three isoforms can be immunoprecipitated by our polyclonal antibody against recombinant QKI (Fig. 1B). In contrast, the fragile X mental retardation protein (FMRP), another KH domain-containing RNA-binding protein, was not recognized by the anti-QKI antibody (Fig. 1B, right). Using this antibody, we analyzed the nuclear and the cytoplasmic extracts derived from the C6 glioma cell line by SDS–PAGE immunoblot. As shown in Figure 1C, a major nuclear isoform of QKI was detected at the predicted position for QKI-5, which was diminished in the cytoplasmic fraction. Two major QKI isoforms were predominantly detected in the cytoplasmic extracts that correspond to QKI-6 and QKI-7.

Figure 1.

Expression of QKI protein isoforms in the qkv/qkv and the wt/qkv littermates. (A) Schematic representation of QKI protein isoforms derived from alternative usage of the C-terminal exons. The QKA1 and QKA2 together with the single KH domain form the RNA-binding domain of QKI. (B) SDS–PAGE analysis of immunoprecipitated 35S-QKI isoforms derived from in vitro translation. The input and immunoprecipitates for corresponding proteins are labeled on the left. (C) Immunoblot analysis of nuclear and cytoplasmic QKI isoforms in the C6 glioma cell line. The signals for the corresponding QKI isoforms are marked on the left. N, nuclear lysate; C, cytoplasmic lysate. (D) Reduction of QKI isoforms in the qkv/qkv brain stem. Whole cell lysates were prepared from the brain stem of a P10 qkv/qkv mouse and wt/qkv littermate, followed by SDS–PAGE immunoblot analysis. The blot was re-probed by the antibody against the house-keeping protein eIF5α as a loading control. The detected proteins are marked on the left. The level of each QKI isoform was determined by densitometry analysis using the NIH image software and was normalized to that of the loading control. The relative quantity of QKI in the wt/qkv mice was normalized to the non-phenotypic littermate control (%) and is indicated on the right.

We then examined QKI protein expression in the whole tissue lysate prepared from the P10 brain stem of a qkv/qkv mouse as well as that of the wt/qkv non-phenotypic littermate. All three major QKI isoforms were detected, among which QKI-6 was most abundant (Fig. 1D). QKI-7 and QKI-5 migrated closely on SDS–PAGE and were difficult to separate in lysates derived from animals older than P20. All three QKI isoforms were reduced in the qkv/qkv brain stem. Noticeably, the reduction of QKI-5 was relatively less severe in comparison with that of QKI-6 and QKI-7.

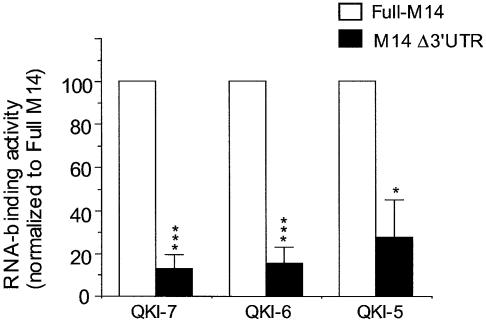

Previous studies indicated that QKI deficiency results in destabilization, mislocalization and abnormal splicing of the mRNA encoding the MBP (10–12), suggesting that MBP mRNA is a candidate target for QKI during myelin development. To examine whether all QKI isoforms can bind the MBP mRNA, we employed an in vitro RNA-binding assay that has been used to evaluate selective activity of a variety of RNA-binding proteins (14,19). As shown in Figure 2, all three QKI isoforms bind MBP mRNA in a MBP 3′UTR-dependent manner (Fig. 2). This result suggests that despite the differential subcellullar localization and developmental expression, all QKI isoforms may contribute to modulate the cellular fate of MBP mRNA, perhaps at different steps of post-transcriptional regulation and/or at different stages during myelin development.

Figure 2.

QKI isoforms bind the 3′UTR of the mRNA encoding the 14 kDa MBP (M14). 35S-QKI isoforms derived from in vitro translation were incubated with biotin-labeled full-length M14, or M14 lacking the 3′UTR (M14Δ3′UTR), before being captured by streptavidin-conjugated magnetic beads. The RNA-bound QKIs were quantitatively analyzed by scintillation counting, in which the RNA-binding activity by full-length M14 was set at 100% for normalization of binding by M14Δ3′UTR in parallel experiments. RNA binding for each QKI isoform was repeated four times (n = 4). Within each experiment, the binding activity of each QKI isoform is comparable. *P < 0.05, ***P < 0.001 (paired t-test).

qkI mRNA isoforms are reduced in both the CNS and the PNS, which is responsible for the diminished expression of QKI proteins

To determine the molecular mechanisms responsible for the reduction of QKI proteins in the qkv/qkv brain, we developed an RPA which allowed us to evaluate the quantitative level of each qkI mRNA isoform encoding the major QKI protein isoforms. RT–PCR was carried out using primers corresponding to the C-terminal coding region of QKI-5, QKI-6 and QKI-7, respectively, as illustrated in Figure 3A. Full-length antisense riboprobes were synthesized by in vitro transcription using cloned RT–PCR fragments as templates (Fig. 3A, right) and subjected to RPA. Each probe is expected to protect the full-length fragment of the corresponding isoform. The predicted sizes of the full-length RPA fragment specific for qkI-5, qkI-6 and qkI-7 are 365, 302 and 323 nt, respectively. Each probe is also expected to protect a 275 nt common fragment derived from the rest of the qkI isoforms. As shown in Figure 3B, the predicted RPA products for all qkI isoforms (marked by arrowheads) were detected in the wild-type mouse brain. Furthermore, low levels of additional RPA products were detected for qkI-5 and qkI-7 (marked by arrows), suggesting the existence of unidentified minor alternative splicing sites for these isoforms. No protected probe fragment was detected in the absence of input mRNA (Fig. 3B) or in the presence of yeast tRNA (data not shown).

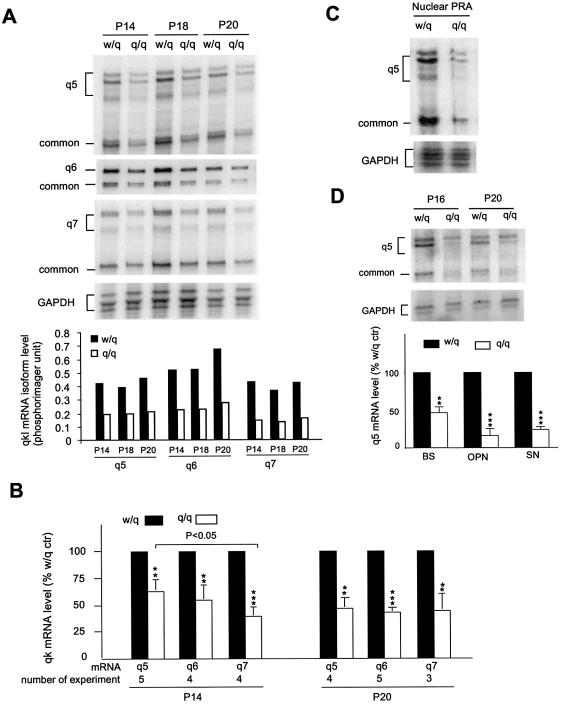

Using the RPA, we analyzed qkI mRNA isoforms in various regions of the nervous system of qkv/qkv and wt/qkv littermates during myelin development. Our previous studies show that QKI is most abundant during active myelination and rapidly declines thereafter (18). Therefore, the active period of myelinogenesis may be the most critical developmental window for the functional requirement of QKI. We first examined qkI mRNA expression in the brain stem, in which reduction of the QKI-5 protein isoform was less severe at the early stage of myelination (Fig. 1D). As shown in Figure 4A, all qkI mRNA isoforms were reduced in the qkv/qkv brain stem at P14, P18 and P20. However, in either wt/qkv or qkv/qkv mice, the quantity of each qkI mRNA isoform, when normalized to the house-keeping GAPDH mRNA, did not show obvious temporal changes during this developmental window for active myelin sheath production (Fig. 4A, bottom). Phosphorimager quantification of several RPAs indicated that the reduction of qkI-5 mRNA in the qkv/qkv brain was less severe (37% reduction) than that of qkI-7 (59% reduction) at P14 (P < 0.05, Fig. 4B). However, by the age of P20, the reductions of all qkI mRNA isoforms, including qkI-5, were not significantly different from each other (53, 57 and 54% reduction for qkI-5, qkI-6 and qkI-7, respectively). This result suggests that the less severe reduction of qkI-5 at P14 was a transient phenomenon in the young qkv/qkv mutant. A similar level of reduction of qkI mRNAs was also detected in the qkv/qkv cerebrum (data not shown). Since nuclear retention of specific mRNA has been found in the qkv/qkv brain (12), we examined qkI mRNA levels in the nuclei isolated from the brain stem of qkv/qkv and wt/qkv littermates. As shown in Figure 4C, a comparable level of reduction of qkI mRNAs was observed in the nuclei and in the whole tissue derived from the qkv/qkv brain (Fig. 4C). This result discounted the possibility that diminished QKI protein in the qkv/qkv brain was due to nuclear retention of the qkI mRNA. We also examined qkI mRNAs in the optic nerve and sciatic nerve derived from qkv/qkv mice and wt/qkv littermates (Fig. 4D). Interestingly, qkI transcripts were markedly reduced in both nerves. Reduced qkI expression was observed in the qkv/qkv sciatic nerve at P16 and P20. Interestingly, the reduction of qkI mRNA in the sciatic nerve was even more severe than that in the brain, despite the fact that hypomyelination is much less profound in PNS than in the CNS of the qkv/qkv mutant (4).

Figure 4.

Reduction of qkI mRNAs in the CNS and PNS during myelin development of the qkv/qkv mutant. (A) Representative RPA gel of reduced qkI mRNA isoform expression in brain stem during active myelin development. The genotype and age of the animals are labeled at the top of each lane. The RPA products for each isoform are marked on the left. The RPA for the house-keeping mRNA GAPDH was used as a loading control. Phosphorimager reading of qkI isoforms in each lane was normalized to that of GAPDH and is shown in the bottom panel. (B) Quantification and statistical analysis of qkI mRNA levels in the brain stem of qkv/qkv mutant and wt/qkv littermates. The level of qkI mRNA in the non-phenotypic wt/qkv littermate control is set as 100% for normalization of reduced qkI mRNA in the qkv/qkv mutant in paired experiments. The number of experiments is indicated at the bottom for each qkI mRNA. **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001 (paired t-test). (C) Reduced qkI mRNAs in the nuclei isolated from the P20 brain stem of qkv/qkv mutant. Nuclei were isolated from wt/qkv and qkv/qkv littermates in parallel experiments, and the level of qkI mRNA was compared. The reduction level is comparable with that in the total RNA (Fig. 4A). (D) Reduction of qkI mRNAs occurred in both the CNS and PNS of the qkv/qkv mutant. (Top) Reduced qkI expression in qkv/qkv sciatic nerve at P16 and P20 detected by the qkI-5 probe. (Bottom) Statistical analysis of phosphorimager quantification of qkI mRNA in brain stem (BS), optic nerve (OPN) and sciatic nerve (SN) derived from the qkv/qkv and the wt/qkv littermate control at P20. **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001 (paired t-test, n = 3).

qkI mRNA isoforms are reduced specifically in myelin-producing cells in the qkv/qkv mutant

To determine whether qkv also affects qkI expression in tissues outside the nervous system, we analyzed qkI expression in the testis and heart of qkv/qkv and wt/qkv littermates. In contrast to the nervous tissues, no significant reduction of qkI expression was observed in heart or testis of the qkv/qkv mice (Fig. 5A), suggesting that qkv affects qkI expression specifically in the nervous system. In the CNS, QKI expression is found not only in the myelinating oligodendrocytes, but also in astrocytes that are not involved in myelination (8). Whether qkI expression is quantitatively reduced in astrocytes has not been determined. To address this question, we analyzed qkI mRNA expression in primary cultures of astrocytes derived from wt/qkv and qkv/qkv littermates. As shown in Figure 5B, in contrast to the marked reduction of qkI in the qkv/qkv brain, a comparable level of qkI expression was observed in astrocytes derived from wt/qkv and qkv/qkv littermates. This result suggests that reduced expression of qkI occurs specifically in oligodendrocytes of the qkv/qkv brain.

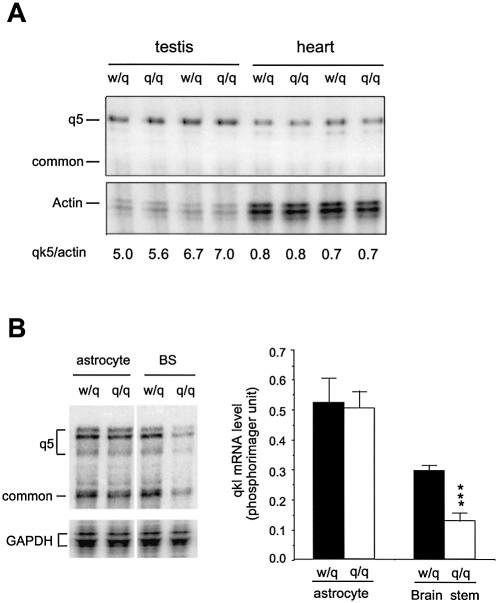

Figure 5.

Reduced qkI expression specifically occurs in myelin-producing cells of the qkv/qkv brain. (A) qkI mRNAs are not reduced in the testis and heart of the qkv/qkv mutant. The genotypes and tissue types are labeled on top of the corresponding lanes. The RPA products are marked on the left. The house-keeping β-actin mRNA is used as a loading control. The ratio of phosphorimager reading of qkI-5 to actin is indicated at the bottom of each lane. (B) qkI mRNAs are reduced in the brain stem but not in the non- myelinating astrocytes. RNA was isolated from P18 brain stem, or from primary cultures of astrocytes derived from individual brain stems of the qkv/qkv mutant and the wt/qkv littermate, as described in Materials and Methods, before being subjected to a parallel RPA. (Left) A representative RPA gel and (right) the statistical analysis of results derived from repeated experiments. ***P < 0.001 (standard t-test, n = 3).

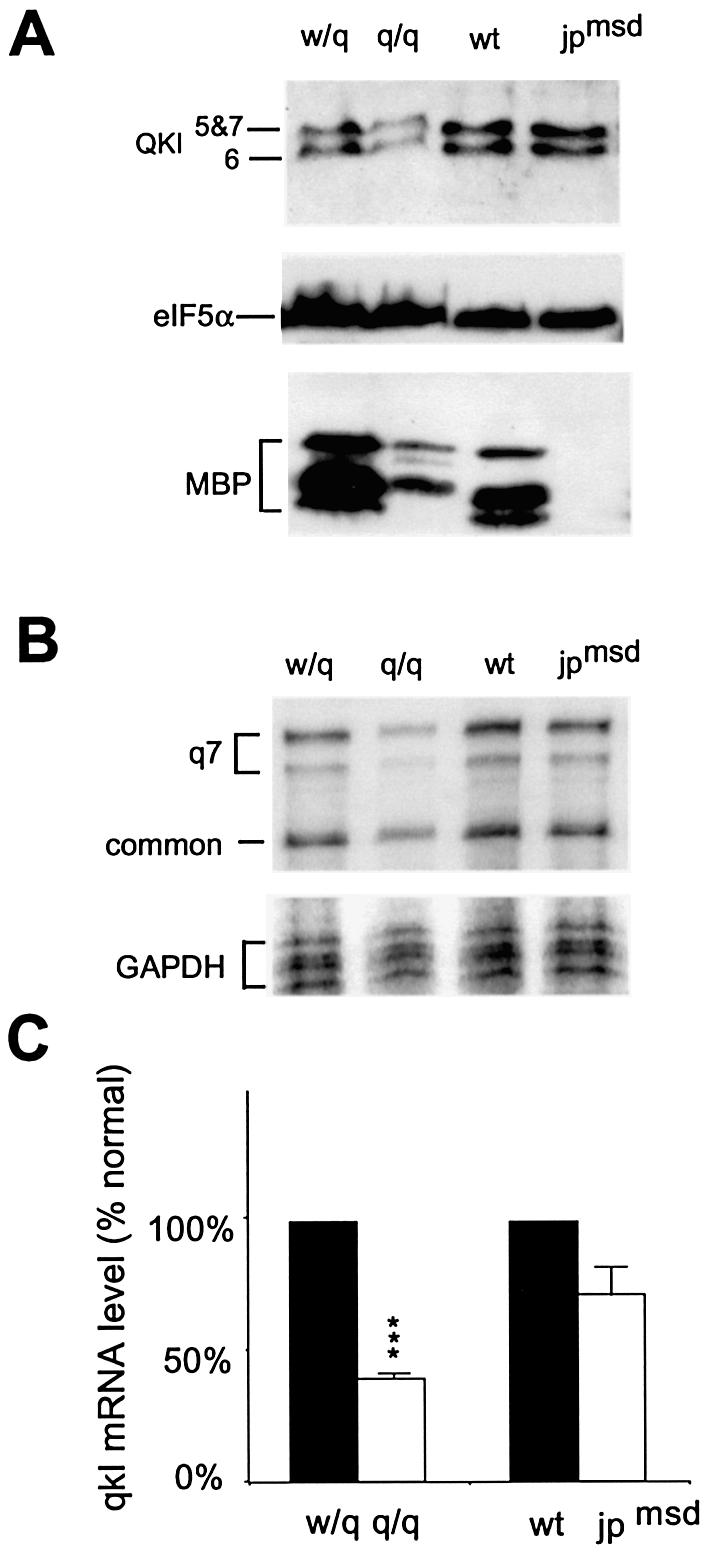

To test whether qkI expression is also reduced in other dysmyelination diseases, we analyzed qkI mRNA and protein isoforms in the jpmsd mutant mice that display more severe hypomyelination than the qkv/qkv mice (5). In the jpmsd mutant mice, apoptosis of mature oligodendrocytes was increased compared with normal mice (20). As a result, the level of MBP was markedly reduced because MBP is expressed at low levels in young oligodendrocytes but is rapidly accumulated during oligodendrocyte maturation and myelin sheath production (2,4,5,18). In contrast, in the jpmsd mutant brain, qkI mRNA and QKI proteins were only slightly reduced when compared with the wild-type littermate without statistical significance (P > 0.05, Fig. 6A–C). This is likely due to the fact that qkI expression is not vigorously elevated in mature oligodendrocytes (Fig. 4A) (18) and therefore it is only mildly affected in the jpmsd mutant. This result clearly indicates that marked reduction of qkI expression observed in the qkv/qkv brain is not a general phenomenon resulting from hypomyelination. Instead, it must represent a specific consequence of the qkv genetic lesion.

Figure 6.

Normal qkI expression in the jpmsd hypomyelination mutant at P18. (A) Reduction of QKI proteins in the qkv/qkv but not in the jpmsd hypomyelination mutant by immunoblot analysis. The genotype of each mutant and the littermate control is indicated at the top of the corresponding lanes and the proteins detected are marked on the left. Note the more severe reduction of MBP in the jpmsd hypomyelination mutant than in the qkv/qkv mutant. (B) Representative RPA indicating significant reduction of qkI mRNA in the qkv/qkv mutant but not in the jpmsd mutant. (C) Phosphorimager quantification of qkI mRNA levels in the qkv/qkv and the jpmsd mutant normalized to their non-phenotypic littermate controls. ***P < 0.001 (paired t-test, n = 3).

qkI mRNA isoforms display normal translation profiles in the qkv/qkv brain

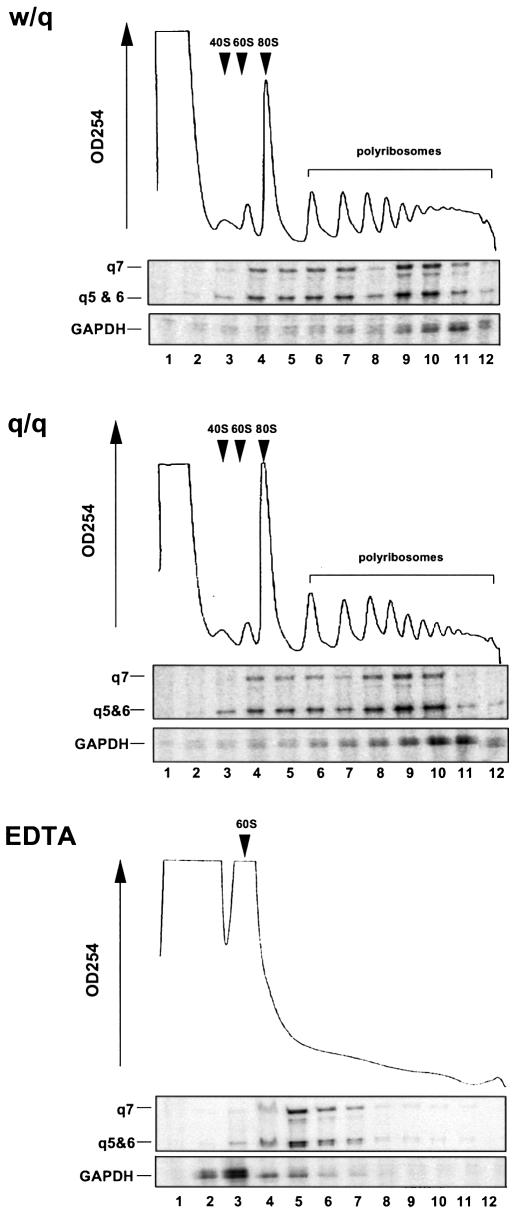

To determine whether deficits in translation may contribute to the diminished expression of QKI proteins, we examined the profile for polyribosome association of qkI mRNAs in the brain of qkv/qkv and wt/qkv littermates, which is a commonly used assay in evaluating translation activity of mRNA in vivo. As shown in Figure 7, the polyribosome profiles in the brain lysates derived from qkv/qkv and wt/qkv littermates were almost identical, indicating normal translation of qkI mRNA in the qkv/qkv mutant brain. In fact, the majority of qkI transcripts co-fractionated with polyribsomes (fractions 6–12), with the most intense qkI signal detected in fractions containing actively translating ribosomes (fractions 9 and 10). EDTA treatment resulted in dissociation of polyribosomes into ribosomal subunits and released the qkI mRNAs into messenger ribonucleoprotein (mRNP) complexes. As a consequence, qkI mRNAs were shifted to fractions toward the top of the gradient (fraction 5), confirming the engagement of qkI mRNAs in translation. This result discounts the possibility that diminished QKI is due to a deficiency in QKI protein synthesis.

Figure 7.

qkI mRNAs are engaged in normal translation in the qkv/qkv mutant brain. Cytoplasmic extracts were prepared from the brain stem of P19 qkv/qkv and their wt/qkv littermates before being fractionated on a 15–45% (w/v) linear sucrose gradient. The separation of ribosomal components was monitored at OD254 and is shown on top of each panel. The distribution of qkI mRNAs and that of the house-keeping GAPDH mRNA in each gradient was analyzed by RPA and superimposed with the OD254 absorption profile. The fraction numbers are indicated at the bottom. EDTA treatment dissociates polyribosomes into subunits, resulting in a shift of mRNA into the top fractions.

DISCUSSION

The above observations provide the first evidence that qkv directly affects the expression level of qkI mRNA isoforms in the nervous system of the qkv hypomyelination mutant. The deficient qkI expression is not a general consequence of hypomyelination, since the jpmsd mutant that harbors more severe hypomyelination than qkv (5) did not show significant reduction of qkI expression (Fig. 6). At the moment, we cannot completely exclude the possibility that the stability of QKI proteins may also be affected in the qkv/qkv brain, perhaps as an indirect effect of abnormal myelin development. However, the fact that the quantitative reduction of qkI mRNA isoforms in the qkv/qkv brain matches with that of the corresponding QKI protein isoforms (Figs 1D and 4B) argues that reduced expression of qkI mRNA isoforms is responsible for the QKI protein deficiency to a large extent. In addition, no abnormalities were detected in the qkv/qkv mutant at several post-transcriptional steps. These include: (i) an identical RPA pattern for qkI mRNA isoforms in the qkv/qkv mutant and the wild-type control (Figs 3 and 4), suggesting normal splicing of the qkI transcript; (ii) comparable reduction of the qkI mRNAs in the nuclei and in the whole tissue derived from the qkv/qkv brain, suggesting normal nuclear-cytoplasmic distribution; (iii) a normal polyribosome association profile of qkI mRNAs in the qkv/qkv brain (Fig. 7), suggesting no translation deficits. Although the above studies did not rule out destabilization of the qkI mRNAs in the qkv/qkv brain, the fact that the qkv lesion is located 5′ to the qkI transcription start site suggests the loss of an enhancer and the deficiency of QKI proteins most likely results from reduced qkI transcription.

In the postnatal mouse brain, QKI proteins are expressed abundantly in the myelinating oligodendrocytes as well as in the non-myelinating astroglia, but not in neurons (8). The normal level of qkI mRNAs in astrocytes derived from the qkv/qkv brain (Fig. 5) suggests that the reduction of qkI mRNAs during active myelination (Fig. 4) occurs specifically in oligodendrocytes, responsible for the diminished immunostaining of QKI proteins in oligodendrocytes reported previously (8). The level of qkI mRNA in the qkv/qkv brain is approximately half that in the wt/qkv littermates (Fig. 4B). Since oligodendrocytes account for about half of the glia cells in the brain, the observed reduction must represent severely diminished qkI expression in oligodendrocytes, and the qkI mRNAs detected in the qkv/qkv brain most likely represent qkI expression in non-myelinating glia. The levels of qkI mRNAs are also markedly reduced in the sciatic nerve at P16 and P20 (Fig. 4D), indicating that qkv affects qkI expression not only in oligodendrocytes of the CNS, but also in Schwann cells of the PNS. However, despite the more profound hypomyelination in the CNS than the PNS of the qkv/qkv mice (4), qkI expression was not more severely reduced in the brain than in the sciatic nerve (Fig. 4D). The lack of correlation between the severity of qkI deficiency and that of hypomyelination in CNS and PNS suggests the possible existence of different mechanisms that regulate myelination at various regions of the nervous system. In fact, a regional difference of hypomyelination in the nervous system is not unique in qkv/qkv mice. Deficiency of Fyn kinase affects myelination in the forebrain, but not in the spinal cord and PNS (21). In contrast, platelet-derived growth factor (PDGF) A knockout mice display myelin deficits more profoundly in the spinal cord and cerebellum as compared with the medulla (22). Despite the variation of hypomyelination severity, deficient qkI mRNA expression in myelin-producing cells of both CNS and PNS, without detectable post-transcriptional abnormalities of qkI mRNA in the qkv/qkv mice, suggest that the qkv deletion most likely affects an enhancer for qkI transcription in myelin-producing cells.

The possible existence of a cell type-specific enhancer for qkI transcription during active myelination is also supported by the fact that qkI-6 and qkI-7 mRNAs in the normal brain are expressed at high levels during the most active period of myelinogenesis (P14–P20) (6,8). These two isoforms account for ∼70% of the brain qkI mRNAs (Fig. 4). In fact, abundant expression of qkI-6 and qkI-7 mRNAs is found only in the nervous system (Figs 4 and 5). In the heart and testis, qkI-5 is the predominant isoform while qkI-6 and qkI-7 are negligible (Fig. 5A). The developmental regulation of qkI-5 mRNA expression is distinct from that of qkI-6 and qkI-7. qkI-5 is expressed at higher levels during embryonic and neonatal development, and gradually declines until it reaches the lowest level at P14 before the peak of myelination (8). Whether the declined expression of qkI-5 mRNA during development is controlled by alternative splicing of the qkI transcript, or alternatively due to transcriptional regulation by an embryonic enhancer, or even by regulation at the level of mRNA stability, is an intriguing question the answer to which still remains elusive.

Although all three major QKI protein isoforms are able to interact with certain mRNA targets such as that encoding MBP (Fig. 2), distinct roles of QKI isoforms in regulating myelination have been reported. The nuclear isoform QKI-5 is implicated in regulating splicing and nuclear export of its mRNA target (11,12), whereas the cytoplasmic QKI-6 and QKI-7 may regulate mRNA stability and localization of mRNA to the myelin sheath (10,18). We observed less severe reduction of the qkI-5 isoform as compared with other qkI isoforms in the qkv/qkv brain stem at the level of both mRNA and protein (Figs 1 and 4). However, this phenomenon appeared to be transient and only occurred at the early stage of myelination (P10–P14). At the peak of myelination (P20), reduction of qkI-5 mRNA was at a similar level to that observed for qkI-6 and qkI-7 in the qkv/qkv brain (Fig. 4B). The severity of QKI-5 reduction at the early stage of myelination geographically correlates with the severity of hypomyelination (8), supporting the hypothesis that QKI-5 also exerts positive roles in myelination. Although over-expression of QKI-5 causes nuclear retention of the MBP mRNA (12), the overall downstream consequence as a result of less severe reduction of QKI-5 in oligodendrocyte development, due to misregulation of multiple oligodendrocyte genes, remains to be determined by future studies. Identification of mRNA targets for each QKI isoform at various developmental stages may ultimately elucidate the roles of QKI in controlling myelin development.

Acknowledgments

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We thank Dr Campagnoni and Dr Artzt for providing the cDNA constructs encoding the MBP and QKI proteins. We also thank Dr Billings-Gagliardi for sharing the jpmsd mutant mice. This work is supported by NMSS grant RG3296 and NIH grant NS 39551 to Y.F.

REFERENCES

- 1.Hardy R.J. (1998) Molecular defects in the dysmyelinating mutant quaking. J. Neurosci. Res., 51, 417–422. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Campagnoni A.T. and Macklin,W.B. (1988) Cellular and molecular aspects of myelin protein gene expression. Mol. Neurobiol., 2, 41–89. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sidman S., Dickie,M. and Appel,S. (1964) Mutant mice (Quaking and Jimpy) with deficient myelination in the central nervous system. Science, 144, 309–311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hogan E.L. and Greenfield,S. (1984) Animal Models of Genetic Disorders of Myelin. Plenum Press, New York, NY. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Billings-Gagliardi S., Adcock,L.H. and Wolf,M.K. (1980) Hypomyelinated mutant mice: description of jpmsd and comparison with jp and qk on their present genetic backgrounds. Brain Res., 194, 325–338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ebersole T.A., Chen,Q., Justice,M.J. and Artzt,K. (1996) The quaking gene product necessary in embryogenesis and myelination combines features of RNA binding and signal transduction proteins. Nature Genet., 12, 260–265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kondo T., Furuta,T., Mitsunaga,K., Ebersole,T.A., Shichiri,M., Wu,J., Artzt,K., Yamamura,K. and Abe,K. (1999) Genomic organization and expression analysis of the mouse qkI locus. Mamm. Genome, 10, 662–669. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hardy R.J., Loushin,C.L., Friedrich,V.L.,Jr, Chen,Q., Ebersole,T.A., Lazzarini,R.A. and Artzt,K. (1996) Neural cell type-specific expression of QKI proteins is altered in quakingviable mutant mice. J. Neurosci., 16, 7941–7949. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Vernet C. and Artzt,K. (1997) STAR, a gene family involved in signal transduction and activation of RNA. Trends Genet., 13, 479–484. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Li Z., Zhang,Y., Li,D. and Feng,Y. (2000) Destabilization and mislocalization of myelin basic protein mRNAs in quaking dysmyelination lacking the QKI RNA-binding proteins. J. Neurosci., 20, 4944–4953. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wu J.I., Reed,R.B., Grabowski,P.J. and Artzt,K. (2002) Function of quaking in myelination: regulation of alternative splicing. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA, 99, 4233–4238. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Larocque D., Pilotte,J., Chen,T., Cloutier,F., Massie,B., Pedraza,L., Couture,R., Lasko,P., Almazan,G. and Richard,S. (2002) Nuclear retention of MBP mRNAs in the quaking viable mice. Neuron, 36, 815–829. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wu J., Zhou,L., Tonissen,K., Tee,R. and Artzt,K. (1999) The quaking I-5 protein (QKI-5) has a novel nuclear localization signal and shuttles between the nucleus and the cytoplasm. J. Biol. Chem., 274, 29202–29210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zhang Y. and Feng,Y. (2001) Distinct molecular mechanisms lead to diminished myelin basic protein and 2′,3′-cyclic nucleotide 3′-phosphodiesterase in qk(v) dysmyelination. J. Neurochem., 77, 165–172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Knapp P.E., Bartlett,W.P. and Skoff,R.P. (1987) Cultured oligodendrocytes mimic in vivo phenotypic characteristics: cell shape, expression of myelin-specific antigens and membrane production. Dev. Biol., 120, 356–365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Feng Y., Gutekunst,C.A., Eberhart,D.E., Yi,H., Warren,S.T. and Hersch,S.M. (1997) Fragile X mental retardation protein: nucleocytoplasmic shuttling and association with somatodendritic ribosomes. J. Neurosci., 17, 1539–1547. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Feng Y., Absher,D., Eberhart,D.E., Brown,V., Malter,H.E. and Warren,S.T. (1997) FMRP associates with polyribosomes as an mRNP and the I304N mutation of severe fragile X syndrome abolishes this association. Mol. Cell, 1, 109–118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zhang Y., Lu,Z., Ku,L., Chen,Y., Wang,H. and Feng,Y. (2003) Tyrosine-phosphorylation of QKI mediates developmental signals to regulate mRNA metabolism. EMBO J., 22, 1801–1810. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ashley C.T. Jr, Wilkinson,K.D., Reines,D. and Warren,S.T. (1993). FMR1 protein: conserved RNP family domains and selective RNA binding. Science, 262, 563–566. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gow A., Southwood,C.M. and Lazzarini,R.A. (1998) Disrupted proteolipid protein trafficking results in oligodendrocyte apoptosis in an animal model of Pelizaeus-Merzbacher disease. J. Cell Biol., 140, 925–934. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sperber B.R., Boyle-Walsh,E.A., Engleka,M.J., Gadue,P., Peterson,A.C., Stein,P.L., Scherer,S.S. and McMorris,F.A. (2001) A unique role for Fyn in CNS myelination. J. Neurosci., 21, 2039–2047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Fruttiger M., Karlsson,L., Hall,A.C., Abramsson,A., Calver,A.R., Bostrom,H., Willetts,K., Bertold,C.H., Heath,J.K., Betsholtz,C. and Richardson,W.D. (1999) Defective oligodendrocyte development and severe hypomyelination in PDGF-A knockout mice. Development, 126, 457–467. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]