Abstract

A series of charge-modified, dye-labeled 2′, 3′-dideoxynucleoside-5′-triphosphates have been synthesized and evaluated as reagents for dye-terminator DNA sequencing. Unlike the commonly used dye-labeled terminators, these terminators possess a net positive charge and migrate in the opposite direction to dye-labeled Sanger fragments during electrophoresis. Post-sequencing reaction purification is not required to remove unreacted nucleotide or associated breakdown products prior to electrophoresis. Thus, DNA sequencing reaction mixtures can be loaded directly onto a separating medium such as a sequencing gel. The charge-modified nucleotides have also been shown to be more efficiently incorporated by a number of DNA polymerases than regular dye-labeled dideoxynucleotide terminators or indeed normal dideoxynucleoside-5′-triphosphates.

INTRODUCTION

The initial sequencing of the human genome (1) was completed predominantly using the dideoxy chain termination method developed by Sanger (2). Two methods have been routinely used, namely dye-primer and dye-terminator; however, with the development of DNA polymerases that more efficiently incorporate dideoxynucleoside triphosphates, the popularity of dye-terminator methods have surpassed dye-primer methods (3–8). The terminator method is less laborious as only one reaction mixture is required for each sequence while dye-primer methods require four reactions. Further more, ambiguities caused by termination with dNTPs rather than dideoxynucleotides are eliminated because they remain unlabeled. The most common detection method is fluorescence, using a set of four spectrally resolved fluorophores attached to the dideoxynucleoside triphosphates, allowing detection of the dye-labeled Sanger fragments from a single four-color reaction (9–13).

A major bottleneck in the workflow of dye-terminator sequencing is the need to separate the sequencing reaction products from fluorescent starting material and breakdown products. If unpurified, the dye-terminators and breakdown products co-migrate with the labeled DNA products during electrophoresis, obscuring sequence information amounting to 20–100 bases or more. Standard purification methods include gel filtration and alcohol precipitation. Extreme care must be taken during precipitation to ensure selective removal of unreacted nucleotides and their breakdown products. If conditions are not carefully controlled, shorter Sanger fragments can be lost or unwanted fluorescent reactants and by-products may not be removed. We have evaluated previously a series of 2′, 3′-dideoxynucleotides having extra negative charge in the linker arm between the nucleobase and fluorescent label. The extra negative charges increase the migration rate of the nucleotides during electrophoresis so they emerge ahead of the bands of sequence products (14). While this effort produced a set of terminators that can be used in ‘direct load’ DNA sequencing, the method suffered from relatively low incorporation efficiency of the dideoxynucleotides. As part of a continuing effort into improving ‘direct load’ dye-terminator sequencing, we have synthesized two sets of positively charged nucleotides, one containing an oligo-lysine side chain, the other an oligo-ε-(N-trimethyl)-lysine between the base and the fluorescent label. Both sets of dideoxynucleotides can be used as reagents for direct load DNA sequencing, with the ε-trimethllysine analogs showing most promise.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Reversed Phase HPLC purifications were performed using a Waters 600 pump controller in conjunction with a 2487 dual wavelength detection system. Ion exchange purifications were carried out using an AKTA Explorer 100 (Amersham Biosciences). Mass spectra were obtained using a Micromass LCT electrospray-TOF spectrometer. Purification solvents were of HPLC grade and pre-filtered through a 0.45 µm membrane prior to use. 5-Propargylaminopyrimidine and 7-propargylamino-7-deazapurines were synthesized according to Hobbs and Cocuzza (9). Fluorescein and rhodamine succinimidyl esters were purchased from Molecular Probes (Eugene, OR) and are pure 5-regioisomers unless stated. The number preceding the ddNTP indicates the number of atoms in the linker arm attached at the five position of pyrimidines and seven position of 7-deazapurines. The linker arm is made up of aminocaproic acid units attached to the propargylamino-modified base. For example, an 11-ddNTP has one caproic acid unit attached to the propargylamino moiety. Trifluoro-acetamido-protected lysine oligomers were obtained from American Peptide (Sunnyvale, CA). Quaternized lysine oligomers were obtained from Bachem (King of Prussia, PA). All other reagents were obtained from Sigma, Aldrich or Fluka unless stated. Abbreviations used throughout this paper are as follows; NHS (N-hydroxysuccinimide), DMF (N,N-dimethylformamide), REG or R6G (5-carboxyrhodamine 6G), TEAB (triethylammonium bicarbonate), TFA (trifluoroacetic acid), DMSO (methyl sulfoxide), TSTU [O-(N-succinimidyl)-1,1,3,3-tetramethyl uronium tetrafluoroborate], DSC (N,N′-disuccinimidylcarbonate), DIPEA (N,N-diisopropylethylamine), DMAP (4-N,N-dimethylaminopyridine).

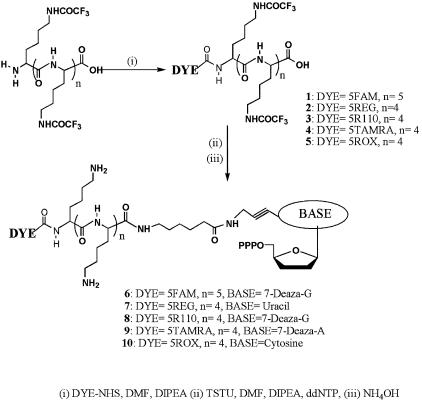

General method for the synthesis of single dye-labeled oligo-lysines (1–5)

To a solution of ε-protected oligo-lysine (0.1 mmol) dissolved in DMSO (3 ml) was added N,N-diisopropylethylamine (280 µl, 10 eq) followed by dye-succinimidyl ester (1.2 eq) in DMF (1 ml). The reaction mixture was stirred at room temperature for 16 h and purified by C18 HPLC (A = 0.1% TFA/H2O v/v, B = 0.1%TFA/MeCN v/v, Waters Deltapak C18 column, 50 × 300 mm, flow 100 ml/min, 0–100% B over 60 min). Product containing fractions (eluted at ∼60% B) were evaporated to dryness in vacuo, triturated with Et2O (50 ml), residual solid dried under high vacuum for 1 h. 1, λmax 498 nm TOF MS observed 1478 (M-H); 2, λmax 526 nm TOF MS observed 1580 (M-H); 3, λmax 505 nm; 4, λmax 555 nm; 5, λmax 581 nm.

General method for the synthesis of single dye-labeled oligo-lysine-modified 2′, 3′-dideoxynucleoside-5′-triphosphates (6–10)

Dye-labeled oligo-lysine (3.9 µmol) was dissolved in DMF (3 ml) and N, N-diisopropylethylamine (0.3 ml, 40 eq) was added followed by TSTU (10 mg, 10 eq). The reaction mixture was stirred at room temperature for 5 min and cooled to 0°C before 11-ddNTP was added in NaHCO3/Na2CO3 buffer (0.1 M, 2 µmol pH 8.5, 2 ml). The ice bath was removed immediately and the reaction stirred at room temperature for 30 min. The product was purified by silica gel chromatography (iPrOH:NH4OH:H2O, 7:3:1 elution), followed by ion exchange chromatography (Q Sepharose, 10 mm × 10 cm column, A = 0.1 M TEAB/MeCN 3:2 v/v, B = 1.0 M TEAB/MeCN 3:2 v/v, 4 ml/min, 0–100% B over 20 column volumes). The product-containing fractions were evaporated to dryness in vacuo and treated with NH4OH (5 ml) for 16 h. The reaction mixture was evaporated to dryness and the product purified by anion exchange chromatography (Q Sepharose, 10 mm × 10 cm column, A = 0.1 M TEAB/MeCN 3:2 v/v, pH 9.2, B = 1.0 M TEAB/MeCN 3:2 v/v, pH 9.2, 4 ml/min, 0–100% B over 20 column volumes), followed by C18 HPLC (A = 0.1 M TEAB, B = MeCN, Waters Deltapak C18 column, 50 × 300 mm, flow 100 ml/min, 0–100% B over 60 min). Product-containing fractions were evaporated to dryness in vacuo and dissolved in TE buffer at pH 8.5. 6, λmax 498 nm, TOF MS observed 1783 (M-H); 7, λmax 525 nm, TOF MS observed 1699 (M-H); 8, λmax 505 nm; 9, λmax 554 nm; 10, λmax 580 nm.

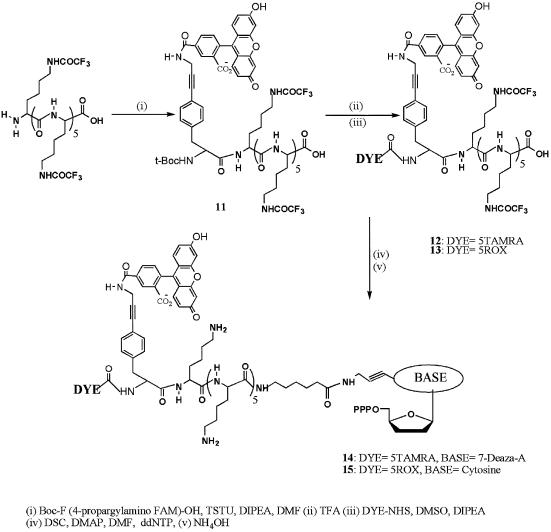

α-N-[β-N-t-butoxycarbonylamido-(4-propargylamido-5-carboxyfluorescein)-phenylalanine]-hexa-(ε-trifluoroacetamido)lysine (11)

To α-t-butoxycarbonyl-(4-progargylamido-5-fluorescein)-phenylalanine (16) (50 mg, 0.051 mmol) dissolved in DMF (2 ml) was added N,N-diisopropylethylamine (90 µl, 10 eq) followed by TSTU (23 mg, 1.5 eq) in DMF (1 ml). The reaction was stirred at room temperature for 1 h and followed by further addition of TSTU (8 mg, 0.4 eq). The reaction was stirred at room temperature for 30 min, and the solution added to hexa-(ε-trifluoroacetamido)lysine (77 mg, 1.0 eq). The solution was stirred at room temperature for a further 16 h. The product purified by C18 HPLC (A = 0.1% TFA/H2O v/v, B = 0.1%TFA/MeCN v/v, Waters Deltapak C18 column, 50 × 300 mm, flow 120 ml/min, 0–100% B over 60 min). The product-containing fractions (50 min) were evaporated to near dryness in vacuo, and the solution lyophilized (31 mg, 30%). TOF MS ES+ found 2023.0 (M + Na+).

(4-Progargylamido-5-fluorescein)-phenylalanine-hexa-(ε-trifluoroacetamido)lysine

α-t-Butoxycarbonyl-(4-progargylamido-5-fluorescein)-phenylalanine-hexa-(ε-trifluoroacetamido)lysine (5, 30 mg, 14.4 µmol) was treated with TFA (10 ml) for 30 min. After evaporation in vacuo, the residue was treated with Et2O (50 ml) to afford a yellow solid. The supernatant liquor was decanted, the residue triturated with further portions of Et2O (2 × 10 ml) and dried under high vacuum (100%). TOF MS ES+ found 1945 (M + Na+).

α-N-5-Dye-(4-progargylamido-5-fluorescein)-phenylalanine-hexa-(ε-trifluoroacetamido)lysine (12, 13)

(4-Progargylamido-5-fluorescein)-phenylalanine-hexa-(ε-tri-fluoroacetamido)lysine (10 mg, 4.9 µmol) was dissolved in DMF (0.2 ml) and N,N-diisopropylethylamine (8.5 µl, 10 eq) added. The solution was added to 5-Dye-NHS (5.0 mg, 1.9 eq) and the reaction mixture stirred at room temperature for 16 h. The product was purified by C18 RP HPLC (A = 0.1% TFA/H2O v/v, B = 0.1%TFA/MeCN v/v, Waters Deltapak C18 column, 50 × 300 mm, flow 120 ml/min, 0–100% B over 60 min). The product-containing fractions (55 min for 12, 58 min for 13) were evaporated to dryness in vacuo (12, 30%; 13, 35%). 12, λmax 498 nm, 551 nm, TOF MS ES– found 2328.4 (M-H); 13, λmax 498 nm, 580 nm, TOF MS ES+ 2447 found (M + H).

Synthesis of energy transfer dye-pair labeled oligo-lysine-modified 2′, 3′-dideoxynucleoside-5′-triphosphates (14, 15)

To a solution of compound 12 or 13 (4.0 µmol) in DMF (1 ml), DSC (10 mg, 8 eq) was added and the reaction mixture was cooled to –60°C. DMAP (1 mg, 4 eq) in DMF (0.2 ml) was added and the temperature was raised to –30°C followed by the addition of 11-ddATP (0.3 ml, 4 mg, 1 eq) in NaHCO3/Na2CO3 (pH 8.5) buffer. The reaction mixture was stirred at room temperature for 1 h, the product purified by anion exchange chromatography (Q Sepharose, 10 mm × 10 cm column, A = 0.1M TEAB/MeCN 3:2 v/v, pH 9.2, B = 1.0 M TEAB/MeCN 3:2 v/v, pH 9.2, 4 ml/min, 0–100% B over 20 column volumes). Product-containing fractions were evaporated to dryness in vacuo and treated with NH4OH (25 ml) for 16 h. The reaction mixture was evaporated to dryness in vacuo and the product purified by anion exchange chromatography (Q Sepharose, 10 mm × 10 cm column, A = 0.1 M TEAB/MeCN 3:2 v/v, pH 9.2, B = 1.0 M TEAB/MeCN 3:2 v/v, pH 9.2, 4 ml/min, 0–100% B over 20 column volumes). 14, λmax 498 nm, 551 nm, TOF MS ES– found 2328.4 (M-H); 15, λmax 498 nm, 580 nm.

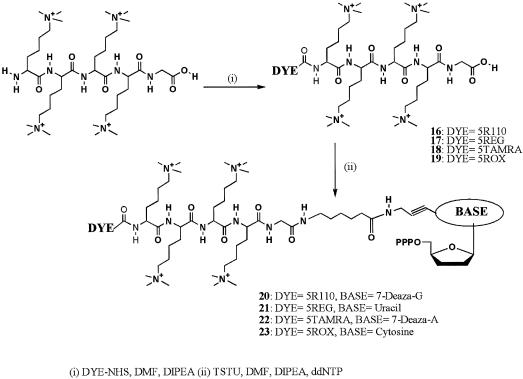

Single dye-labeled trimethyllysine peptides (16–19)

Synthesis was carried out as for compounds 1 and 2. The R110 reaction mixture was treated with NH4OH (10 ml) for 1 h prior to purification. The desired product was purified by cation exchange chromatography (Resource S, 6 ml column, A = 0.1 M TEAB/MeCN 3:2 v/v, pH 9.2, B = 1.0 M TEAB/MeCN 3:2 v/v, pH 9.2, 6 ml/min, 0–100% B over 20 column volumes). Product-containing fractions were evaporated to dryness in vacuo, the residue co-evaporated with EtOH (3 × 10 ml) before further drying under high vacuum. 16, λmax 505 nm, TOF MS ES+ found 556 (M + H/2), 371 (M + H/3); 17, λmax 529 nm, TOF MS ES+ found 598 (M + H/2), 399 (M + H/3); 18, λmax 552 nm; 19, λmax 580 nm.

Dye-labeled-oligo-trimethyllysine-modified 2′,3′-dideoxynucleoside-5′-triphosphates (20–23)

Dye-labeled peptides (16–19, 6.5 µmol) were dissolved in DMSO (5 ml) then N, N-diisopropylethylamine (23 µl, 20 eq) and TSTU (20 mg, 10 eq) added. The reaction mixture was stirred at room temperature for 30 min then cooled to 0°C before 11-ddNTP in NaHCO3/Na2CO3 buffer (0.1 M, 6.5 µmol pH 8.5, 5 ml) added. The ice bath was removed immediately and the reaction stirred at room temperature for 1 h. Water (50 ml) was added to the reaction mixture then the product purified by cation exchange chromatography (SP Sepharose, 5 ml column, A = water/MeCN 3:2 v/v, B = 1.0 M TEAB/MeCN 3:2 v/v, pH 9.2, 6 ml/min, 0–100% B over 20 column volumes). Product-containing fractions were evaporated to dryness in vacuo and the product further purified by cation exchange chromatography (Mono S, 10 mm × 10 cm column, A = 0.1 M TEAB/MeCN 3:2 v/v, pH 9.2, B = 1.0 M TEAB/MeCN 3:2 v/v, pH 9.2, 4 ml/min, 0–100% B over 20 column volumes). Product-containing fractions were evaporated to dryness in vacuo then the residue co-evaporated with MeOH (3 × 10 ml), dried under high vacuum then dissolved in TE buffer at pH 8.5. 20, λmax 505 nm, TOF MS ES+ found 887 (M + Na/2), 876 (M + H/2). 21, λmax 529 nm, TOF MS ES+ found 911 (M + Na/2), 615 (M + 2Na/3); 22, λmax 551 nm; 23, λmax 580 nm.

α-N-[α-N-t-Butoxycarbonylamido-(4-propargylamido-5-carboxyrhodamine-110)-phenylalanine]-tetra(trimethyl)lysine-glycine (24)

α-t-Butoxycarbonyl-(4-progargylamido-5-bistrifluoroacetamido-rhodamine110)-phenylalanine (16) (150 mg, 0.17 mmol) was dissolved in DMSO (3 ml) then N,N-diisopropylethylamine (0.3 ml, 10 eq) added followed by TSTU (57 mg, 1.1 eq). The reaction was stirred at room temperature for 1 h then the solution added to tetra-trimethyllysine-glycine (190 mg, 1 eq) and the solution stirred at room temperature for 16 h. The product was purified by cation exchange chromatography (SP Sepharose 5 ml, A = 0.1 M TEAB/MeCN 3:2 v/v, pH 9.2, B = 1.0 M TEAB/MeCN 3:2 v/v, pH 9.2, 6 ml/min, 0–100% B over 20 column volumes). Product-containing fractions were evaporated to dryness in vacuo then co-evaporated with MeOH (3 × 15 ml). The residue was dissolved in water (50 ml) and NH4OH (10 ml) added. The reaction was stirred at room temperature for 1 h then evaporated to dryness in vacuo. λmax 505nm, TOF MS ES+ found 708 (M/2), 471 (M/3).

α-N-[(4-Propargylamido-5-carboxyrhodamine-110)-phenylalanine)]-tetra(trimethyllysine-glycine) (25)

This was essentially synthesized as reported for 4-propargylamido-5-carboxyfluorescein)-phenylalanine)-hexa-(ε-trifluoroacetamido)lysine. λmax 505nm, TOF MS ES+ found 658 (M+H)/2

α-N-[5-Dye-(4-progargylamido-5-carboxyrhodamine-110)-phenylalanine)]-tetra(trimethyllysine-glycine) (26, 27)

α-N-(4-Propargylamido-5-carboxyrhodamine-110)-phenylalanine)-tetra(trimethyllysine-glycine) (25: 36 mg, 25 µmol) was dissolved in DMSO (3 ml) and N,N-diisopropylethylamine (43 µl, 10 eq) added. To the solution was added 5-Dye-NHS (2.5 eq) and the reaction mixture stirred at room temperature for 16 h. The product was purified by cation exchange chromatography (SP Sepharose 5 ml column, A = 0.1 M TEAB/MeCN 3:2 v/v, pH 9.2, B = 1.0 M TEAB/MeCN 3:2 v/v, pH 9.2, 6 ml/min, 0–100% B over 20 column volumes) and the product-containing fractions were evaporated to dryness in vacuo. 26, λmax 498 nm, 551 nm, TOF MS ES+ found 1726 (M + H), 863 (M + H/2); 27, λmax 498 nm, 580 nm, TOF MS ES+ found 916 (M/2), 610 (M/3).

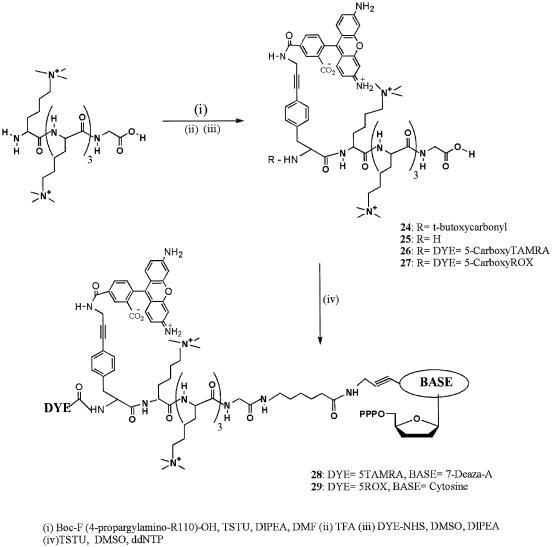

Synthesis of energy transfer dye-pair labeled oligo-trimethyllysine-modified 2′,3′-dideoxynucleoside-5′-triphosphates (28, 29)

To compound 26 or 27 (6.0 µmol) dissolved in DMSO (3 ml), DIPEA (10 µl, 10 eq) and TSTU (28 mg, 15 eq) were added. The reaction mixture was stirred at room temperature for 30 min and 11-ddNTP (HNEt3 salt, DMSO solution, 1.0 eq) added. The reaction mixture was stirred at room temperature for 1 h, the product purified by cation exchange chromatography (Resource S, 6 ml column, A = water/MeCN 3:2 v/v, B = 1.0 M TEAB/MeCN 3:2 v/v, pH 9.2, 5 ml/min, 0–100% B over 20 column volumes). Product-containing fractions were evaporated to dryness in vacuo and co-evaporated with MeOH (3 × 10 ml) before further purification by cation exchange chromatography (Mono S, 10 mm × 10 cm column, A = water/MeCN 3:2 v/v, pH 9.2, B = 1.0 M TEAB/MeCN 3:2 v/v, pH 9.2, 4 ml/min, 0–100% B over 20 column volumes). Product-containing fractions were evaporated to dryness in vacuo, co-evaporated with MeOH (3 × 10ml), and dried under high vacuum. The product was dissolved in TE buffer at pH 8.5. 28, λmax 498 nm, 551 nm, TOF MS ES– found 783 (M/3); 29, λmax 498 nm, 580 nm, TOF MS ES– found 825 (M/3).

Terminator reactivity and sequencing reactions

The reactivity of the synthetic dye-labeled dideoxynucleoside triphosphates was determined as described by Finn et al. (14). A typical sequencing reaction (20 µl) contained the following reagents: 50 mM Tris (pH 8.5), 5 mM MgCl2, 200 µM of dATP, TTP, dCTP, 1000 µM dITP, 20 U of thermally stable DNA polymerase and the corresponding dye-labeled nucleotides. Reaction mixtures were thermally cycled using the following conditions; 95°C for 20 s, 50°C for 30 s, 60°C for 2 min. Reactions were held at 4°C until purification and analysis. For precipitated reactions 2 µl of 7.5 M ammonium acetate and 30 µl of chilled absolute ethanol were added. After mixing and incubating for 20 min the product DNA was precipitated by centrifugation at room temperature for 15 min using a standard lab bench microcentrifuge set on high speed (10 000–16 000 g). Supernatants were removed by aspiration and the DNA pellet rinsed with 200 µl of 70% ethanol. The tubes were re-centrifuged for 5 min and supernatants removed. DNA pellets were stripped of liquid under vacuum at room temperature for 2 min without taking them to complete dryness. To the reaction was added 6–8 µl of formamide loading dye (95% formamide, 50 mM EDTA, pH 8.0, 0.2 mg/ml new fuchsin) then mixed by vortexing for 0.5–1 min at room temperature. Re-suspended DNA was denatured at 70–72°C for 3 min and the tubes quenched on ice. Aliquots of 2–5 µl were then loaded in wells of sequencing gels for analysis. For directly loaded sequences, an aliquot of reaction mixture was removed and treated with formamide (1:1 vol) and 2 µl of suspended product analyzed as above.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

To migrate in the opposite direction to fluorescent Sanger fragments during electrophoresis, the dye-labeled dideoxynucleoside triphosphates and potential fluorescent breakdown products should carry a net positive charge at the pH of electrophoretic separation. Initial efforts focused on oligo-lysines as the source of positive charge. The ε-amino moiety is known to have a pKa of ∼10, which should be protonated at the pH of separation, typically pH 7.5–8.5. The major advantages of using oligo-lysines as the charge carrier is the wide range of protecting group strategies compatible with nucleotide chemistry and the ease of synthesis should oligo-lysines of different lengths be required.

Initial experiments demonstrated that five lysine residues were sufficient to remove fluorescent artifacts from a sequencing gel using rhodamine-labeled dideoxynucleotides, and six lysine residues for fluorescein-labeled dideoxynucleotides (data not shown). Trifluoroacetamide was chosen as the ε-amino protecting group for the synthesis of oligo-lysines. The monomer is readily available, couples in high yield during the stepwise synthesis of the peptide and the protecting group is routinely used in the synthesis of dye-labeled nucleotides (9).

Labeling of oligo-lysines with simple, single dyes was carried out in DMF containing N,N-diisopropylethylamine using the appropriate dye-succinimidyl active esters (Scheme 1). Purification by C18 HPLC eluting with a gradient of water/TFA to MeCN/TFA yielded the desired products which were thoroughly dried prior to conjugation to the nucleotide using O-(N-succinimidyl)-N,N,N′,N′-tetramethyluronium tetrafluoroborate as the activating reagent. Purification by anion exchange chromatography followed by deprotection with NH4OH yielded the desired product, which was further purified by anion exchange chromatography at pH 9.2.

Scheme 1. Synthesis of single dye-labeled oligo-lysine modified 2′, 3′-dideoxynucleoside-5′-triphosphates.

Energy transfer dye-terminators with oligo-lysines were synthesized by attachment of the 4-propargylamino-phenylalanine nucleus (16) to the peptide via O-(N-succinimidyl)-N,N,N′,N′-tetramethyluronium tetrafluoroborate activation (Scheme 2). This was followed by quantitative removal of the boc-protecting group with neat TFA and attachment of the second dye in DMSO via the corresponding succinimidyl ester. The energy transfer dye-labeled peptides were purified by C18 HPLC and then conjugated to the desired dideoxynucleotide using the method described by Nampalli et al. (16). The product was purified by anion exchange chromatography, deprotected with NH4OH followed by repurification by anion exchange chromatography at pH 9.2.

Scheme 2. Synthesis of FRET labeled oligo-lysine modified 2′, 3′-dideoxynucleoside-5′-triphosphates.

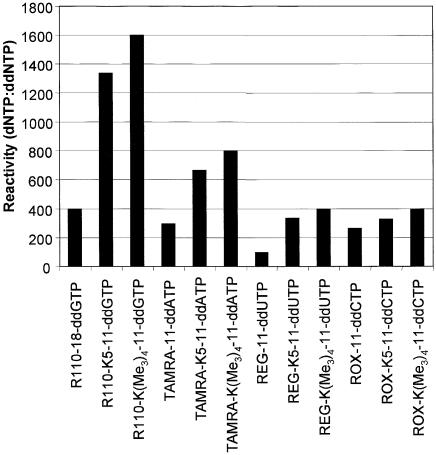

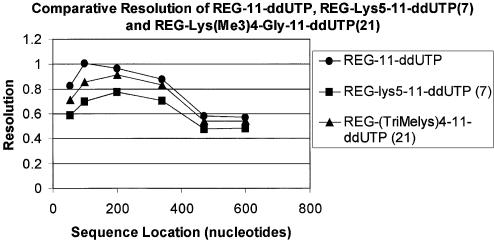

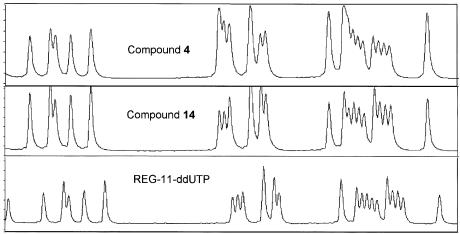

Terminator reactivity was determined by titration of dideoxynucleotide in to a single color sequencing reaction as described earlier (14). Each nucleotide carrying an oligo-lysine charge carrier was more efficiently incorporated by ThermoSequenase™ II DNA polymerase than the corresponding dye-labeled nucleotide without charged linker. This observation held true for a number of other DNA polymerases (data not shown) and studies are continuing in this area to further characterize the observed increase in reactivity (Fig. 1).

Figure 1.

Incorporation efficiency of dye-labeled oligo-lysine and oligo- trimethyllysine modified dideoxynucleoside-5′-triphosphates by Thermo Sequenase II.

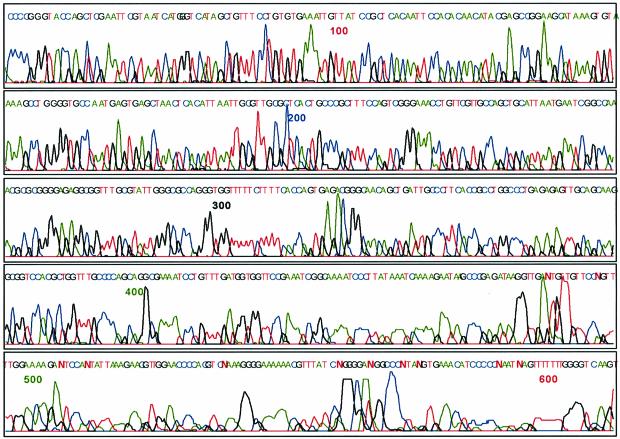

A four-color sequencing reaction using an M13 template was set up as described using optimized concentrations of dye-labeled nucleotides with ThermoSequenase II. A 2 µl aliquot was analyzed on an ABI 377 Prism™ Genetic Analyzer. The electropherogram showed the absence of unreacted nucleotide and breakdown products and that the primary sequence was as expected (Fig. 2). However, sequencing reactions with lysine-modified terminators showed lower resolution across the electropherogram in comparison with regular dye-labeled nucleotides. Single color sequencing reactions, comparing compound 7 with REG-11-ddUTP were carried out to further examine this observation and peak-to-peak resolution measurements determined using the following equation to express resolution:

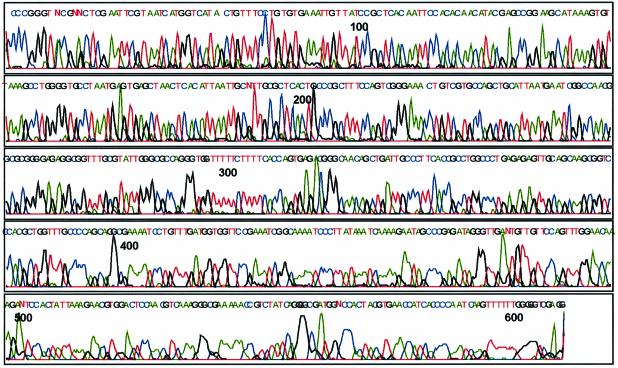

Figure 2.

Direct load DNA sequence using oligo-lysine modified dideoxynucleoside-5′-triphosphate terminators 6, 7, 14 and 15. The color representation is blue (C), red (T), green (A) and black (G).

R = 2ΔVe/(Wa + Wb)

where, R = resolution, Ve = retention time, Wa = width of peak A, Wb = width of peak b (width measured at half height).

From Figure 3 it is clear that the presence of the oligo-lysine modification decreases peak-to-peak resolution over the full size range by as much as 30%. We hypothesized that this was due to the acid–base equilibrium of the lysine side chains causing heterogeneity of total net charge within the population of oligonucleotide fragments of identical length, which resulted in the observed band broadening. We subsequently demonstrated that decreasing the pH of the electrophoresis gel loading solution, indeed, improved resolution early in the sequence. However, there was no improvement in peak-to-peak resolution beyond 350 bases in the chromatogram. To overcome the lack of resolution in the latter part of the electropherogram, we decided to investigate a linker containing ε-trimethyllysine, which contains a quaternary nitrogen that would have constant charge independent of the pH at which separation occurred.

Figure 3.

Effect on resolution versus read length using charge-modified terminators 7 and 21 in a single color sequencing reaction.

The trimethyllysine peptide was synthesized with a glycine residue at the C-terminus to allow the use of commercially available solid supports. Due to coupling inefficiencies the longest peptide synthesized contained four consecutive trimethyllysine residues. We opted to use this pentamer in conjunction with neutral fluorophores, which meant substituting Rhodamine 110 for Fluorescein. The peptide linker was labeled at the N-terminus with an excess of R110 or REG using succinimidyl active esters (Scheme 3). The desired product was purified by cation exchange chromatography and conjugated to the desired dideoxynucleotide using a DMSO solution of the nucleotide and O-(N-succinimidyl)-N,N,N′,N′-tetramethyluronium tetrafluoroborate activation. Two rounds of cation exchange chromatography purified the charge-modified nucleotides, 20–23. The energy transfer compounds were also synthesized by attachment of the R110 containing cassette (16) to the crude peptide followed by cation exchange chromatography (Scheme 4). Removal of the boc group with TFA and attachment of the second dye was achieved using conditions identical to the lysine series. Conjugation to the dideoxynucleoside-5′-triphosphate in DMSO to yield 28 and 29 was achieved using TSTU to activate the peptide and purification by two rounds of cation exchange chromatography.

Scheme 3. Synthesis of single dye-labeled oligo-trimethyllysine-modified 2′, 3′-dideoxynucleoside-5′-triphosphates.

Scheme 4. Synthesis of FRET labeled oligo-trimethyllysine modified 2′, 3′-dideoxynucleoside-5′-triphosphates.

Reactivity and electrophoretic resolution of each nucleotide and oligonucleotide product was obtained from single color sequencing reactions using a mutant ThermoSequenase I DNA polymerase. From Figures 3 and 4 it can be seen that the resolution of the quaternized lysine labeled nucleotide 21 is improved with respect to the lysine analog 7. A four-color sequencing reaction was then set up using optimized concentrations of dye-labeled nucleotides 20, 21, 28 and 29. The reaction was thermally cycled as described and a 2 µl aliquot of reaction mixture analyzed by electrophoresis. The electropherogram indicated the absence of unreacted nucleotide and by-products and the sequence obtained was as expected (Fig. 5). Peak resolution was improved compared with the lysine series and the overall read-length comparable with sequence obtained using regular dye-labeled nucleotides. These reaction samples can also be directly loaded onto a capillary sequencing machine (e.g. MegaBACE™). However, directly loading samples onto a capillary sequencer is more complicated as samples are electro-kinetically loaded, a process which is dramatically effected by the ionic strength of the sample. With slight modification to the sequencing reaction buffer to decrease the overall ionic strength, the sequencing reactions can be directly injected after a simple dilution of the completed reaction with water. Sequencing results obtained are similar to those seen in Figure 5. Notably, unreacted nucleotide dye-blobs are absent from the resulting electropherogram. Further optimization of reaction conditions and work flow are under investigation.

Figure 4.

Effect of different charge carriers on resolution using charge modified terminators 7 and 21 in a single color sequencing reaction.

Figure 5.

Direct load DNA sequence using oligo-trimethyllysine-modified dideoxynucleoside-5′-triphosphate terminators 20, 21, 28 and 29. The color representation is blue (C), red (T), green (A) and black (G).

The reactivity of dye-labeled oligo-trimethyllysine- modified dideoxynucleoside-5′-triphosphates with DNA polymerases was compared with the oligo-lysine-modified terminators and unmodified dye-terminators (Fig. 1). In each case, oligo-trimethyllysine-modified terminators were incorporated much more efficiently than the unmodified dye-terminators. The reactivity of charge-modified dye-labeled ddGTP, ddATP and ddTTP terminators is 3–4-fold higher than the unmodified dye-terminators. This is the opposite of the case when the net charge on the terminators is negative which reduces reactivity to one-quarter to one-tenth that of uncharged dye-terminators (14).

CONCLUSION

The aim of this research was to remove a major bottleneck from dye-terminator sequencing methods, namely the requirement for post-reaction purification to remove unreacted nucleotide or fluorescent breakdown products that obscure observation of sequence information during electrophoresis. Our previous efforts focussed upon incorporation of negative charge into the dye-terminator structure so that unwanted fluorescent artefacts would migrate ahead of sequence. This approach was hampered by inefficient incorporation of the charge-modified dye-terminators that was only in part compensated by using long linker arms between charge carrier and base, and using a charge-modified DNA polymerase.

As a continuation of this research, two new sets of charge-modified dye-terminators incorporating a short cationic peptide chain were synthesized. With either set of terminators, there were no fluorescent artifacts that would obscure sequence obtained upon electrophoresis when reaction products were loaded directly on the electrophoresis gel. Incorporation efficiency of the charge-modified terminators by a number of DNA polymerases was improved 300–400% compared with regular dye-terminators. The ε-trimethyllysine-modified nucleotides showed better performance than the lysine analogs, which yielded poor peak resolution limiting read-lengths to <500 bases. Studies are ongoing to further explore the applicability of these nucleotides to direct load DNA sequencing particularly with capillary electrophoresis. The efficient incorporation of positively charged nucleotides by DNA polymerases is very interesting and this may help in designing new, powerful nucleotide substrates and inhibitors. These could find uses in such diverse areas as genetic analysis and antiviral drug design.

REFERENCES

- 1.International Human Genome Mapping Consortium (2001) A physical map of the human genome. Nature, 409, 934–941. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sanger F., Nicklen,S. and Coulson,A.R. (1977) DNA sequencing with chain-terminating inhibitors. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA, 74, 5463–5467. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Smith L.M., Fung,S., Hunkapiller,M.W., Hunkapiller,T.J. and Hood,L.E. (1985) The synthesis of oligonucleotides containing an aliphatic amino group at the 5′ terminus: synthesis of fluorescent DNA primers for use in DNA sequence analysis. Nucleic Acids Res., 13, 2399–2412. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Voss H., Schwager,C., Wirkner,U., Sproat,B., Zimmermann,J., Rosenthal,A., Erfele,H., Stegemann,J. and Ansorge,W. (1989) Direct genomic fluorescent on-line sequencing and analysis using in vitro amplification of DNA. Nucleic Acids Res., 17, 2517–2527. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bergot B.J., Chakerian,V., Connell,C.R., Eadie,J.S., Fung,S., Hershey,N.D., Lee,L.G., Menchen,S.M. and Woo,S.L., (1994) US Patent No. 5 366 860.

- 6.Reeve M.A. and Fuller,C.W. (1995) A novel thermostable polymerase for DNA sequencing. Nature, 376, 796–797. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Tabor S. and Richardson,C.C. (1990) Selective inactivation of the exonuclease activity of bacteriophage T7 DNA polymerase by in vitro mutagenesis. J. Biol. Chem., 264, 5447–6458. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tabor S. and Richardson,C.C. (1990), DNA sequence analysis with a modified bacteriophage T7 DNA polymerase—effect of pyrophosphorolysis and metal ions. J. Biol. Chem., 265, 8322–8328. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hobbs F.W. Jr and Cocuzza,A.J. (1991) US Patent No. 5 047 519.

- 10.Smith L.M., Sanders,J.Z., Kaiser,R.J., Hughes,P., Doss,C., Conell,C.R., Heiner,C., Kents,S.B.H. and Hood,L. (1986), Fluorescence detection in automated DNA sequencing. Nature, 321, 674–678. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Prober G.M., Trainor,G.L., Dam,R.J., Hobbs,F.W., Robertson,C.W., Zagursky,R.J., Cocuzza,A.J., Jensen,M.A. and Baumeister,K. (1987) A system for rapid DNA sequencing with fluorescent chain-terminating dideoxynucleotides. Science, 238, 336–341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Swedlow H., Zhang,J.Z., Chen,D.Y., Harke,H.R., Grey,R., Wu,S. and Dovichi,N., (1991) Three DNA sequencing methods based on capillary gel electrophoresis and laser-induced fluorescence. Anal. Chem., 63, 2835–2841. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Brazill S.A., Kim,P.H. and Kuhr,W.G. (2001) Capillary gel electrophoresis with sinusoidal voltammetric detection: a strategy to allow four-‘color’ DNA sequencing. Anal. Chem., 73, 4882–4890. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Finn P.J., Sun,L., Nampalli,S., Xiao,H., Nelson,J.R., Mamone,J.A., Grossmann,G., Flick,P.K., Fuller,C.W. and Kumar,S. (2002) Synthesis and application of charge modified dye-labeled dideoxynucleoside-5′-triphosphates to ‘direct-load’ DNA sequencing. Nucleic Acids Res., 30, 2877–2885. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lee L.G., Connell,C.R., Woo,S.L., Cheng,R.D., McArdle,B.F., Fuller,C.W., Halloran,N.D. and Wilson,R.K. (1992) DNA sequencing with dye-labeled terminators and T7 polymerase: effect of dyes and dNTPs on incorporation of dye-terminators and probability analysis of termination fragments. Nucleic Acids Res., 20, 2471–2483. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Nampalli S., Khot,M. and Kumar,S. (2000) Fluorescence energy transfer terminators for DNA sequencing. Tetrahedron Lett., 41, 8867–8871. [Google Scholar]