Abstract

The effects of three levels of treatment integrity (100%, 50%, and 0%) on child compliance were evaluated in the context of the implementation of a three-step prompting procedure. Two typically developing preschool children participated in the study. After baseline data on compliance to one of three common demands were collected, a therapist implemented the three-step prompting procedure at three different integrity levels. One integrity level was associated with each demand. The effects of the integrity levels were examined using multielement designs. The results indicate that compliance varied according to the level of treatment integrity that was in place.

Keywords: noncompliance, preschool children, three-step prompting, treatment integrity

Treatment integrity refers to the extent to which a treatment is implemented as designed. In research, behavioral interventions are likely to be implemented with near-perfect integrity, but in practice settings this is not always so. A number of studies have examined the effects of behavioral interventions when implemented at less than perfect levels of integrity. For example, Northup, Fisher, Kahng, Harrel, and Kurtz (1997) evaluated varying levels of integrity for a differential reinforcement plus time-out procedure. Appropriate behavior was reinforced on 100% of occasions, 50% of occasions, or 25% of occasions. In addition, time-out was implemented for aberrant behavior using these same values. Results showed that intervention effects were maintained at 100% integrity levels even when time-out was implemented at 50% integrity. Vollmer, Roane, Ringdahl, and Marcus (1999) examined differential reinforcement of alternative behavior (DRA) at varying integrity levels. They found that after exposure to DRA at 100% integrity (i.e., appropriate behavior was reinforced each time it occurred; problem behavior was never reinforced), lower levels of integrity did compromise intervention effects. However, participants exhibited a general bias toward appropriate behavior during many of the varying integrity levels, presumably because their recent history with the 100% integrity phase predisposed them to engage in appropriate behavior.

Although these studies provide a start, more research on the effects of behavioral interventions at varying levels of integrity is needed. The purpose of this study was to examine the effects of varying levels of treatment integrity on child compliance in the context of the implementation of a multistep prompting procedure (Horner & Keilitz, 1975). This study extends the existing research on treatment integrity of behavioral interventions by conducting a parametric analysis of an antecedent-based intervention (prompting) as opposed to a consequence-based intervention (reinforcement).

Method

Participants and Setting

Jake (a 4-year-old boy) and Cara (a 4-year-old girl), the first 2 children nominated for the study, participated. Neither of the participants had a psychiatric diagnosis or a developmental disability, both had age-appropriate language skills, and both had been reported to be at least occasionally noncompliant by a parent or a preschool instructional assistant. However, both participants had been observed to exhibit behaviors necessary to comply with the instructions used in the study. All sessions were conducted in a small tutoring room or classroom or on the playground at the participants' school. Three to six sessions were conducted per day, 2 to 3 days per week. A graduate research assistant, who had no prior interactions with the participants before the study began, served as the therapist.

Response Measurement and Definitions

The dependent variable—compliance—was defined as doing what the therapist described in the instruction that she presented within 10 s. Data were collected on the percentage of trials in which participants complied with the instruction presented by the therapist within 10 s. Compliance during each trial was recorded by trained observers using data sheets. A second independent observer recorded compliance during at least 50% of sessions for all participants. Interobserver agreement was obtained on a trial-by-trial basis by comparing observers' records. Agreement was assessed by dividing the number of agreements by the number of agreements plus disagreements and multiplying by 100%. Agreement values ranged from 93% to 100% for both participants during both baseline and three-step prompting integrity phases. Data on independent-variable integrity were also collected by recording whether or not the therapist delivered the appropriate prompt during the 50% and 100% integrity sessions. Independent-variable integrity values were 100% for all sessions for both participants. Finally, interobserver agreement on independent-variable integrity was collected during at least 25% of three-step prompting sessions. Agreement on independent-variable integrity was 100% for both participants.

A trial consisted of the presentation of a verbal instruction by the therapist (baseline and three-step prompting) and progression through the prompt hierarchy if the participant did not comply with the instruction (three-step prompting). During the three-step intervention, compliance was recorded only if the participant complied within 10 s of the first prompt; compliance after the second or third prompt was not counted as compliance. In both baseline and intervention phases, each trial consisted of one instruction. Ten trials were presented during each 10-min session at a rate of one per minute.

Procedure

Prior to baseline, participants' instructional assistants were asked to identify three instructions with which the children often did not comply. These specific instructions were then presented during the study. The instructions used were “give me the [snack item],” which was delivered in the small tutoring room where participants ate snacks; “put the toy away [in its storage area],” which was delivered when the participants were in the classroom; and “come here,” which was delivered when the participants were on the playground. The therapist attempted to equalize the effort involved in complying with the three instructions by presenting them so that participants had to move the same distance to comply with each. For example, for the “give me the [snack item]” and “come here” instructions, the therapist stood approximately 2 m from the participant when delivering the instructions. For the “put the toy away” instruction, the therapist presented the instruction when the participant was approximately 2 m from the toy storage bin.

Some toys, educational materials, and other students were present in the rooms and on the playground in which the study was conducted. During baseline, compliance resulted in brief praise by the therapist. If the participant did not comply with the instruction, the therapist did not respond (i.e., did not provide additional prompts or praise).

During the three-step prompting intervention, the therapist presented the same instructions that were presented during baseline. Compliance resulted in brief praise. If the participant did not comply with the first instruction, the therapist obtained eye contact with the participant by first stating the participant's name and (if necessary) gently touching his or her chin. The therapist then re-presented the instruction while simultaneously modeling the correct performance. If compliance occurred during or any time after the therapist stated the participant's name, compliance was not recorded. Compliance resulted in brief praise. If the participant did not comply within 10 s, the therapist re-presented the instruction while simultaneously guiding the participant to perform the activity. Children were permitted to continue with their ongoing activities between instructions.

Three different levels of treatment integrity (i.e., 100%, 50%, and 0%) were implemented. Each level of integrity was associated with one of the three instructions. Before baseline sessions began, the three instructions were randomly assigned to one of the three levels of integrity for each participant. For Jake, “give me the [snack item]” was associated with 100% integrity, “put the toy away” was associated with 50% integrity, and “come here” was associated with 0% integrity. For Cara, “come here” was associated with 100% integrity, “put the toy away” was associated with 50% integrity, and “give me the [snack item]” was associated with 0% integrity. During 100% integrity sessions, the therapist implemented the three-step procedure for each instruction for which the participant did not comply. During 50% integrity sessions, the therapist implemented the three-step procedure on half the trials during each session. Before each session began, a fixed-ratio (FR) 2 schedule was used to identify the trials during which the three-step procedure would be implemented. During sessions, the therapist had access to a sheet of paper informing her of this schedule. Of course, because the second and third steps of the three-step procedure could be implemented only contingent on the participant not complying with the initial instruction, this resulted in the procedure being implemented on approximately 50% of trials. During 0% integrity sessions, the therapist did not implement the three-step procedure on any trials.

Experimental Design

A multielement design with a baseline phase was used to determine the effects of the varying integrity levels of the three-step prompting procedure on compliance.

Results and Discussion

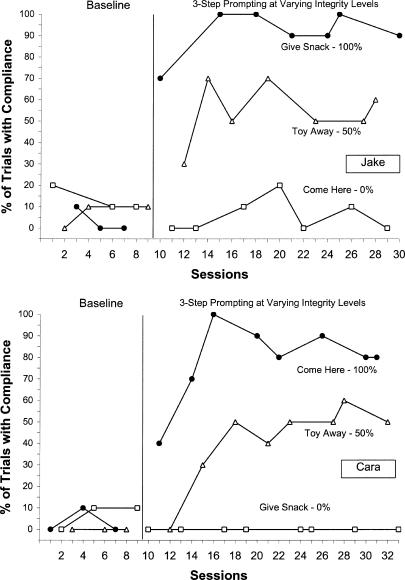

Figure 1 depicts the percentage of trials with compliance across baseline and evaluation of the three-step prompting levels of integrity. During baseline, both participants exhibited low levels of compliance with all instructions. During the three-step prompting levels of integrity, compliance with instructions associated with 100% integrity improved substantially (Ms = 91% and 79% for Jake and Cara, respectively), compliance with instructions associated with 50% integrity improved somewhat (Ms = 54% and 41% for Jake and Cara, respectively), and compliance with instructions associated with 0% integrity did not improve or decreased (Ms = 6% and 0% for Jake and Cara, respectively).

Figure 1. Percentage of trials with compliance across baseline and three-step prompting integrity levels (i.e., 100%, 50%, and 0%).

Results of this study suggest that the integrity with which the three-step prompting procedure is implemented has a large impact on its effects. These results are somewhat inconsistent with previous research on the integrity of behavioral interventions. For example, Northup et al. (1997) found that intervention effects were maintained at 100% integrity levels, even when time-out was implemented at 50% integrity. In the current study, intervention effects at 50% integrity were well below those at 100% integrity. The reason for the discrepancy could be that in the previous study, participants were first exposed to behavioral interventions at 100% integrity, whereas in the current study, this did not occur.

These results have implications for the use of three-step prompting as a method to increase compliance among children. Inconsistent implementation of the procedure, which may be likely to occur when parents or teachers become busy or when they must supervise many children, may result in less than ideal effects. On the other hand, consistent implementation of the procedure may produce substantial increases in compliance.

It should be emphasized that the three-step procedure was actually implemented during 100% or 50% of trials in which participants were noncompliant, not during 100% or 50% of total trials. That is, three-step prompting could be implemented only when participants did not comply with the first instruction. Nevertheless, clear differences in compliance among integrity levels are apparent, which suggests that responding came under the control of the contingencies (and perhaps the context associated with the contingencies) during the first few sessions of each integrity condition and remained under that control for the duration of each phase.

Analysis of within-session responding in the current study is suggestive of some of the behavioral mechanisms responsible for the results. During the 100% integrity condition, when participants did not comply, they were noncompliant mainly during the first half of trials; little noncompliance occurred during the later trials of a session. In addition, the therapist frequently had to progress to the third step of the procedure; little compliance occurred on the second step. This suggests that the guided compliance component of the procedure may have functioned as a punisher for not complying on subsequent trials.

One limitation of this study is that no control for activity preference was used. That is, it could have been that one of the three activities that participants engaged in (i.e., eating snack, playing on the playground, playing with toys in a classroom) was more preferred than another. Even though instructions were randomly assigned to integrity levels and baseline levels of compliance were low, differential preference could have influenced compliance.

Future research should examine the effects of treatment integrity when implementing other behavioral interventions. It is possible that some interventions, such as time-out, may not require near-perfect integrity, whereas others may need perfect or near-perfect implementation. Also, variable integrity schedules may yield different results. In the current study, FR 2 may have made implementation of guided compliance predictable. Perhaps a variable-ratio schedule at a similar (or even more degraded) level of integrity would be less detrimental.

References

- Horner R.D, Keilitz I. Training mentally retarded adolescents to brush their teeth. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis. 1975;8:301–309. doi: 10.1901/jaba.1975.8-301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Northup J, Fisher W, Kahng S, Harrel B, Kurtz P. An assessment of the necessary strength of behavioral treatments for severe behavior problems. Journal of Developmental and Physical Disabilities. 1997;9:1–16. [Google Scholar]

- Vollmer T.R, Roane H.S, Ringdahl J.E, Marcus B.A. Evaluating treatment challenges with differential reinforcement of alternative behavior. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis. 1999;32:9–23. [Google Scholar]