Abstract

We evaluated interventions designed to reduce multiply controlled problem behavior exhibited by a young boy with developmental disabilities, using a multiple baseline design. Each intervention was designed to address a specific social function of problem behavior. Results showed that the separate interventions were useful in reducing problem behavior, and terminal schedules were reached by way of schedule thinning (attention condition) and delays to reinforcement (tangible and escape conditions).

Keywords: aggression, disruption, functional analysis, multiple control

Previous research has shown that problem behavior may be sensitive to multiple sources of reinforcement (Smith, Iwata, Vollmer, & Zarcone, 1993). Smith et al. evaluated the self-injurious behavior (SIB) of 3 individuals and determined that SIB was sensitive to both socially mediated positive reinforcement and reinforcement that was not socially mediated (automatic). Next, interventions were evaluated in a combined multiple baseline and reversal design for each function of SIB. For 2 participants, results of the treatment suggested that SIB was multiply controlled, whereas results for the remaining participant suggested that SIB was sensitive to only one source of reinforcement. Despite these results, the generality of this finding may be limited in that all participants displayed behavior that was maintained, in part, by automatic reinforcement. Thus, the approach used by Smith et al. has not yet been applied to multiple sources of socially mediated reinforcement.

The purpose of the current investigation was to replicate the procedures of Smith et al. (1993) by evaluating separate interventions for three sources of socially mediated reinforcement identified via functional analysis. We also attempted to thin the schedule of reinforcement for each treatment to address the difficulty of implementation.

Method

Participant and Setting

Walsh was a 7-year-old boy who had been diagnosed with mental retardation and who engaged in aggression (i.e., hitting and kicking others, spitting, and biting) and disruption (throwing objects and property destruction). He engaged in unprompted vocalizations and communicated using full sentences. He was admitted to an inpatient hospital facility for the assessment and treatment of problem behavior. All sessions were conducted by trained researchers on the hospital unit. The unit consisted of individual bedrooms as well as a community living room and kitchen area. All sessions were conducted 4 days per week, two to three times each day, and were 10 min in duration.

Response Measurement and Reliability

Frequency data were collected on problem behavior (i.e., aggression and disruption), compliance with instructions (defined as completion of an instruction following a verbal or modeled prompt), and appropriate requests (e.g., saying, “Can I play with that?”). Interobserver agreement was calculated for 67% of functional analysis sessions, 30% of baseline sessions, and 49% of treatment sessions. Agreement was calculated by dividing each session into 60 intervals (10 s each), dividing the smaller number of responses by the larger number of responses within each interval, averaging these scores across all intervals, and converting the resulting product to a percentage. Agreement for problem behavior averaged 90% (range, 67% to 100%) during the functional analysis, 88% (range, 73% to 95%) during the baseline analysis, and 99% (range, 81% to 100%) during the treatment analysis. Agreement averaged 98% (range, 95% to 100%) for appropriate requests for tangible items and 98% (range, 89% to 100%) for compliance during baseline, and 98% (range, 75% to 100%) for appropriate requests for tangible items and 98% (range, 78% to 100%) for compliance during the treatment analysis.

Procedure

Functional Analysis

Prior to the functional analysis, a preference assessment was conducted to identify preferred stimuli for inclusion in subsequent sessions (Roane, Vollmer, Ringdahl, & Marcus, 1998). Next, a functional analysis was conducted using procedures similar to those described by Iwata, Dorsey, Slifer, Bauman, and Richman (1982/1994). During the functional analysis, four test conditions (attention, escape, alone, and tangible) were compared to a control condition in a multielement design.

Treatment

Following the functional analysis, separate interventions were developed to address each maintaining reinforcement contingency. The treatments were introduced sequentially using a multiple baseline design. All baseline conditions were identical to the relevant test conditions from the functional analysis. During the attention baseline condition, a brief reprimand (e.g., “Don't do that; you're hurting me.”) was delivered contingent on problem behavior. The treatment for the attention function consisted of noncontingent attention (NCA) in which attention was initially delivered continuously while problem behavior no longer resulted in adult attention (i.e., extinction). The schedule of reinforcement during NCA was thinned from a continuous schedule of attention to a terminal schedule of fixed-time (FT) 5 min using procedures similar to those described by Marcus and Vollmer (1996).

During the tangible baseline condition, brief access to preferred tangible items was presented for 30 s contingent on problem behavior. The treatment for the tangible condition consisted of differential reinforcement of alternative behavior (DRA), in which problem behavior no longer produced access to items (extinction) and all appropriate requests resulted in 30-s access to preferred items. During the tangible treatment, the delay to reinforcement was increased from no delay (0 s) following instances of appropriate verbal behavior to a 5-min delay, using procedures similar to those described by Vollmer, Borrero, Lalli, and Daniel (1999).

Finally, in the escape baseline condition, escape from instructional demands was provided for 30 s contingent on problem behavior. During the treatment for the escape function, problem behavior no longer resulted in a 30-s break from instructional demands (extinction), and a DRA component was implemented in which each instance of compliance resulted in a 30-s break. During the 30-s break, Walsh typically attempted to initiate conversation with the therapist and to request preferred tangible items. Thus, he also received access to tangible items and attention during the 30-s break from demands. During the escape treatment, the schedule of reinforcement for compliance was subsequently thinned from a fixed-ratio (FR) 1 to a variable-ratio (VR) 3 using procedures similar to those described by Lalli et al. (1999).

Results and Discussion

During the functional analysis, high rates of problem behavior were observed during the attention (M = 3.9 responses per minute), escape (M = 6.2), and tangible (M = 3.1) conditions, compared to the alone (M = 0.9) and control (M = 0.05) conditions, suggesting behavioral sensitivity to adult attention, escape from demands, and access to tangible items (data not presented in Figure 1; these were reported previously in Borrero, Vollmer, Borrero, & Bourret, 2005).

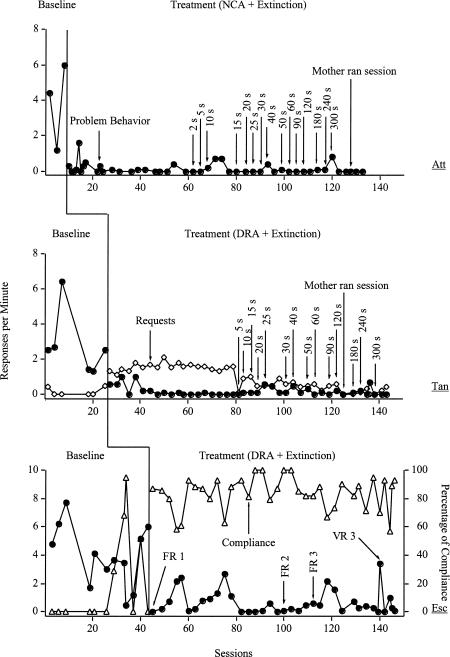

Figure 1. Results of the treatment analysis for the attention condition (top), tangible condition (middle), and escape condition (bottom).

Responses per minute of problem behavior are shown on the y axis on all panels, and the percentage of compliance is shown on the secondary y axis for the escape condition.

Figure 1 shows the results of the treatment evaluation for the attention, tangible, and escape conditions. The baseline phases include sessions from the pretreatment functional analysis. During the attention analysis, NCA plus extinction resulted in an immediate decrease in rates of problem behavior (M = 0.2 responses per minute), which remained low as the reinforcer–reinforcer interval increased from 2 s (Session 61) to 5 min (Session 120). Walsh's mother served as therapist during one session (Session 122), in which rates of problem behavior remained low.

Prior to the tangible treatment analysis, two additional baseline sessions were conducted after the initial functional analysis sessions. The intervention resulted in a decrease in problem behavior (M = 0.2 responses per minute) relative to baseline (M = 2.8). Appropriate requests for items increased in the treatment condition (M = 0.9) relative to baseline (M = 0.2), and problem behavior remained low as the delay to reinforcement was increased from 5 s (Session 80) to 5 min (Session 139). As expected, the rate of requests decreased slightly throughout the analysis, because there were fewer opportunities to request items during delay thinning. Walsh's mother conducted one session (Session 122) with no delay to reinforcement, and problem behavior did not occur.

In the escape treatment evaluation, nine baseline sessions were conducted in addition to the initial functional analysis sessions. The implementation of DRA plus extinction resulted in a decrease in problem behavior (M = 0.7 responses per minute) compared to baseline levels (M = 3.7), and compliance increased from baseline (M = 20%) to treatment (M = 81%). Although problem behavior was more variable in the escape-based treatment than in the other treatment conditions, the schedule requirement for escape was successfully increased from an FR 1 (Session 42) to a VR 3 (Session 140).

Hanley, Iwata, and McCord (2003) reported that as many as 15% of functional analyses revealed multiple control of problem behavior, which suggests that interventions designed to address multiply controlled problem behavior represent an important area for investigation. From a practical perspective, treatment of multiply controlled problem behavior may be difficult for caregivers to implement because separate interventions for each reinforcer must be implemented with regard to the specific establishing operation in place. Therefore, in the current investigation, separate interventions were developed for each function while the parameters of each intervention (e.g., delays and response requirement) were thinned to enhance the overall practicality of their implementation.

Results of this analysis are similar to those reported by Smith et al. (1993) in that systematic decreases in problem behavior were observed when treatments were introduced for the separate reinforcers that maintained problem behavior. In addition, the current investigation extends the work of Smith et al. by suggesting the effectiveness of the assessment model when applied to multiple sources of socially mediated reinforcement.

The multiple baseline evaluation conducted in the current study was somewhat unique in that the independent variable (treatment) was introduced sequentially across functions rather than participants, settings, or response topography. Typically, multiple baseline designs include the same independent variable across participants, settings, responses, or functions. By contrast, in the current investigation, different interventions were implemented (NCA and two types of DRA contingencies) across the respective baselines. Although these interventions can be considered similar in terms of being based on the results of a functional analysis, they involved the delivery of different reinforcers and contingencies and thus may also be conceptualized as three separate independent-variable manipulations. Future investigations in the treatment of multiply controlled behavior may evaluate the effectiveness of separate and identical interventions across all baselines to determine the optimal procedures for evaluating treatments for multiply controlled problem behavior.

Acknowledgments

We thank John Borrero for his helpful comments on an earlier version of this manuscript.

References

- Borrero C.S.W, Vollmer T.R, Borrero J.C, Bourret J. A method for evaluating parameters of reinforcement during parent-child interactions. Research in Developmental Disabilities. 2005;26:503–600. doi: 10.1016/j.ridd.2004.11.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hanley G.P, Iwata B.A, McCord B.E. Functional analysis of problem behavior: A review. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis. 2003;36:147–185. doi: 10.1901/jaba.2003.36-147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iwata B.A, Dorsey M.F, Slifer K.J, Bauman K.E, Richman G.S. Toward a functional analysis of self-injury. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis. 1994;27:197–209. doi: 10.1901/jaba.1994.27-197. (Reprinted from Analysis and Intervention in Developmental Disabilities, 2, 3–20, 1982) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lalli J.S, Vollmer T.R, Progar P.R, Wright C, Borrero J, Daniel D, et al. Competition between positive and negative reinforcement in the treatment of escape behavior. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis. 1999;32:285–296. doi: 10.1901/jaba.1999.32-285. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marcus B.A, Vollmer T.R. Combining noncontingent reinforcement and differential reinforcement schedules as treatment for aberrant behavior. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis. 1996;29:43–51. doi: 10.1901/jaba.1996.29-43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roane H.S, Vollmer T.R, Ringdahl J.E, Marcus B.A. Evaluation of a brief stimulus preference assessment. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis. 1998;31:605–620. doi: 10.1901/jaba.1998.31-605. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith R.G, Iwata B.A, Vollmer T.R, Zarcone J.R. Experimental analysis and treatment of multiply controlled self-injury. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis. 1993;26:183–196. doi: 10.1901/jaba.1993.26-183. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vollmer T.R, Borrero J.C, Lalli J.S, Daniel D. Evaluating self-control and impulsivity in children with severe behavior disorders. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis. 1999;32:451–466. doi: 10.1901/jaba.1999.32-451. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]