Abstract

We have studied the mutagenic properties of ribonucleotide analogues by reverse transcription to understand their potential as antiretroviral agents by mutagenesis of the viral genome. The templating properties of nucleotide analogues including 6-(β-D-ribofuranosyl)-3,4-dihydro-8H-pyrimido[4,5-c](1,2)oxazin-7-one, N4-hydroxycytidine, N4-methoxycytidine, N4-methylcytidine and 4-semicarbazidocytidine, which have been reported to exhibit ambiguous base pairing properties, were examined. We have synthesized RNA templates using T3 RNA polymerase, and investigated the specificity of the incorporation of deoxyribonucleoside triphosphates opposite these cytidine analogues in RNA by HIV and AMV reverse transcriptases. Except for N4-methylcytidine, both enzymes incorporated both dAMP and dGMP opposite these analogues in RNA. This indicates that they would be highly mutagenic if present in viral RNA. To study the basis of the differences among the analogues in the incorporation ratios of dAMP to dGMP, we have carried out kinetic analysis of incorporation opposite the analogues at a defined position in RNA templates. In addition, we examined whether the triphosphates of these analogues were incorporated competitively into RNA by human RNA polymerase II. Our present data supports the view that these cytidine analogues are mutagenic when incorporated into RNA, and that they may therefore be considered as candidates for antiviral agents by causing mutations to the retroviral genome.

INTRODUCTION

Genetic diversities of retroviruses and RNA viruses caused by their higher mutation rates allow the viral population to escape host immune responses, resulting in rapid antiviral drug resistance (1,2). The higher mutation rates may result in many defective virions, because deleterious mutations in essential genes should also take place (2). Thus, it has been suggested that these viruses exist near their ‘error thresholds’, maximal mutation rates to sustain production of infectious progenies (3). Induction of mutations exceeding these thresholds could lead these viruses to extinction, which is termed error catastrophe or lethal mutagenesis (4–7). Among the various types of mutagen, nucleotide analogues, which do not incorporate into DNA, may be suitable for this purpose. Therefore, it is important to explore the use of such analogues for their potential to serve as novel antiviral agents. Indeed, it has been suggested that ribavirin, a broad-spectrum antiviral ribonucleoside, forces poliovirus and hantavirus into error catastrophe (4,8,9). A small increase in the mutation frequency by 5-azacytidine or 5-fluorouracil causes dramatic reduction in the survival levels of poliovirus, vesicular stomatitis virus, foot-and-mouth disease virus and lymphocytic choriomeningitis virus (10–13). In retroviruses, experiments with 5-hydroxy-2′-deoxycytidine (5-OH-dC) and 5-aza-5,6-dihydro-2′-deoxycytidine (KP-1212) it has been demonstrated that it is possible to increase mutation rates and eradicate HIV by repeated passages in the presence of these deoxyribonucleoside analogues (6,14). However, deoxyribonucleoside analogues may also be incorporated into host genomic DNA, and mutations in the host genome may be induced. Unlike deoxynucleosides, ribonucleoside analogues are not directly incorporated into the host genomic DNA. Ribonucleoside analogues can be incorporated into cellular RNA resulting in altered proteins. However, it will be a transient aberration, because mRNAs have short half-lives and proteins tolerate a wide variety of mutations (15–19). Therefore, ribonucleosides might be more suitable for use in error catastrophe than deoxynucleosides (20). We have studied the mutagenic properties of several ribonucleotide triphosphate analogues using a reverse transcription assay to determine their mutagenic potential; mutagenic analogues can be considered as potential antiretroviral agents by inducing mutations to the viral genome, which in turn leads to lethal mutagenesis.

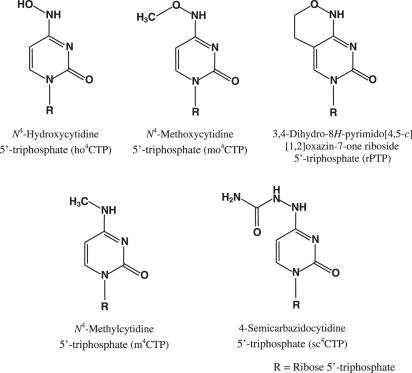

6-(β-D-ribofuranosyl)-3,4-dihydro-8H-pyrimido[4,5-c](1,2)oxazin-7-one triphosphate (rPTP) has been shown to induce U-to-C and C-to-U transition mutations in an in vitro retroviral replication model using phage T3 RNA polymerase and AMV reverse transcriptase (21). It was reported that the triphosphates of N4-hydroxycytidine (ho4C), N4-methoxycytidine (mo4C) and N4-methylcytidine (m4C) exhibited ambiguous properties in polymerization (22–24), and N4-aminodeoxycytidine triphosphate can be incorporated in place of both dCTP and dTTP (25,26). We have found that 4-semicarbazidocytidine triphosphate, a N4-aminocytidine derivative, can be incorporated as UTP by phage RNA polymerase (27) (Figure 1). These N4-cytidine analogues except m4C show ambiguous base pairing properties by amino-imino tautomerism; the presence of the electronegative element on the N4-amino group reduces their tautomeric constants close to unity (28,29). In the present study, we have investigated the specificity of incorporation of deoxyribonucleoside triphosphates opposite these cytidine analogues in RNA by HIV and AMV reverse transcriptases. Except m4C, HIV and AMV reverse transcriptases incorporated both dAMP and dGMP opposite these analogues when present in RNA. This indicates that these substrates would be highly mutagenic if present in the viral RNA. To study the basis of the differences among the analogues in the incorporation ratios of dAMP to dGMP, we have measured the kinetics of incorporation of dNTPs opposite the analogues at defined positions in RNA templates using a primer extension protocol. In addition, we have examined whether the triphosphates of these analogues were incorporated competitively into RNA by human RNA polymerase II.

Figure 1.

Structure of N4-modified cytidine analogues used in this study.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Materials

Recombinant HIV reverse transcriptase was expressed in Escherichia coli by using plasmid p6HRT-PROT kindly provided by Dr S. F. Le Grice of National Institutes of Health (30), and purified by Ni-NTA agarose (QIAGEN). AMV reverse transcriptase, Tfl DNA polymerase, T3 RNA polymerase, HeLa nuclear extract and calf intestinal alkaline phosphatase were purchased from Promega (Madison, WI).

Synthesis of ribonucleoside analogues N4-Hydroxycytidine 5′-triphosphate

N4-Hydroxycytidine 5′-triphosphate was prepared as described previously (31) with a slight modification. Briefly, CTP (30 mg) was treated in 0.2 ml of 2 M hydroxylamine hydrochloride (pH 5.0) at 55°C for 5 h. The samples of ho4CTP were purified by reverse phase high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) using an ODS-120A (TOSOH) column eluted with 3% methanol-10 mM triethylammonium bicarbonate (pH 6.8), at 0.7 ml/min. The samples were further purified by anion exchange HPLC using a DEAE-2sw (TOSOH) column [0.06 M disodium hydrogenphosphate-20% acetonitrile (pH 6.6) and 0.7 ml/min] and then purified by reverse phase HPLC again as described above.

N4-Methoxycytidine 5′-triphosphate

N4-Methoxycytidine 5′-triphosphate was prepared as described previously (23), and purified by three-step HPLC as ho4CTP.

N4-Methylcytidine 5′-triphosphate

N4-Methylcytidine 5′-triphosphate was prepared by bisulfite-catalyzed transamination of CTP (32). CTP (25 mg) was mixed with a 0.25 ml solution containing 4 M monomethylamine, 0.4 M sodium bisulfite and 0.1 M sodium dihydrogenphosphate (pH 7.5) and reacted at 60°C for 2 days. The samples of m4CTP were purified by HPLC as described for ho4CTP.

4-Semicarbazidocytidine 5′-triphosphate

4-Semicarbazidocytidine 5′-triphosphate was prepared according to the method described for 4-semicarbazidocytidine (33) with a slight modification. CTP (15 mg) was reacted in a solution (0.1 ml) containing 1 M semicarbazide hydrochloride and 0.5 M sodium bisulfite (pH 5.4) at room temperature for 4 h. To this solution was added 4 ml of 0.5 M sodium phosphate (pH 6.5) and 1.8 ml of water and the reaction kept at 37°C for 2 h. The crude sc4CTP sample was diluted by addition of 80 ml water, loaded on to a DE52 column (2 × 9 cm), which was washed with 50 ml of 25 mM sodium phosphate (pH 7) and 50 ml of 25 mM sodium phosphate (pH 7) supplemented with 7 M urea. The triphosphate was eluted in a gradient from 0.025 mM to 0.4 M sodium phosphate (pH 7), containing 7 M urea. The sample was loaded onto another DE52 column (1.4 × 3 cm), and washed with 50 ml of 0.05 M ammonium bicarbonate. sc4CTP eluting in with 1 M ammonium bicarbonate. The sample was further purified by reverse phase HPLC using an ODS-120A (TOSOH) column [3% methanol-10 mM triethylammonium bicarbonate (pH 6.8) and 0.7 ml/min].

Synthesis of the nucleosides and nucleotides, and confirmation of the modified triphosphates

Modified ribonucleosides, ho4C, mo4C, sc4C and m4C, and their 2′/3′-monophosphates were prepared with cytidine and 2′/3′-CMP, respectively, in an analogous reaction as used for the preparation of triphosphates. ho4C, m4C, mo4C and sc4C were shown to be >98% pure in two HPLC systems, and verified by 1H-NMR and mass spectrometry. The nucleosides were shown to be co-eluted in two HPLC systems with the nucleosides obtained by digestion of triphosphate analogues. For the preparation of its 2′/3′-monophosphate, RNA containing rP synthesized as below was digested with RNase T2, and purified by HPLC. All the triphosphates and monophosphates showed the same ultraviolet (UV) absorbance as the nucleosides at acidic, neutral and basic pHs.

6-(β-D-Ribofuranosyl)-3,4-dihydro-8H-pyrimido [4,5-c](1,2)oxazin-7-one 5′-triphosphate (rPTP)

6-(β-D-Ribofuranosyl)-3,4-dihydro-8H-pyrimido[4,5-c](1,2) oxazin-7-one, and its 5′-triphosphate were prepared as described previously (34).

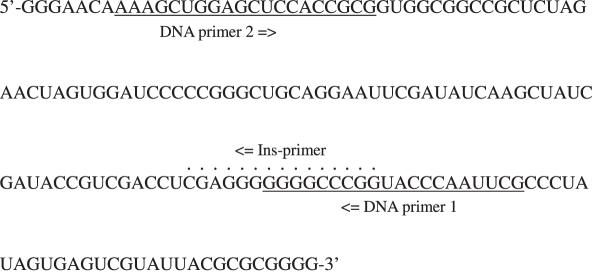

Transcription by T3 RNA polymerase

The DNA fragment of pBluescript II SK (−) digested by BssHII purified on agarose gel were used as a template to produce 155 nt runoff transcripts from T3 promoter. Standard transcription reaction mixtures (20 μl) contained 40 mM Tris–HCl (pH 7.4), 6 mM MgCl2, 2 mM spermidine, 10 mM NaCl, 10 mM DTT, 0.5 mM rNTPs, 50 ng DNA template, 20 U RNase inhibitor (Wako, Osaka, Japan), and 10 U T3 RNA polymerase. The mixtures were incubated at 37°C for 1 h. For the incorporation of the cytidine analogues, they were added in place of one of four normal nucleotides in an equal or 10-fold excess concentration of the normal nucleotides. After the transcription, the DNA template was degraded by incubation at 37°C for 30 min with 2 U DNaseI. The reactions were monitored by 7 M urea 8% denaturing PAGE. The reactions were terminated with 1/10 volume of 20 mM EGTA, deproteinated with phenol/chloroform/isoamyl alcohol (25:24:1) and desalted by Centri-Sep spin column. These RNA transcripts were used as templates for reverse transcription (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Sequence of RNA template and primer binding site. RNA templates contain ho4C, mo4C, rP or sc4C in place of U, and m4C in place of C.

Analysis of base composition

The HPLC analysis of RNA transcripts was performed as described previously (35) with slight modification. The dried transcripts were dissolved in digestion mixtures (30 μl) containing 50 mM Tris–HCl (pH 7.4), 10 mM MgCl2 and 0.4 U snake venom phosphodiesterase I. The mixtures were incubated at 37°C for 90 min. Subsequently, 0.2 U snake venom phosphodiesterase I and 2 U calf intestinal alkaline phosphatase were added to the reactions, and then incubation was continued at 37°C for 2 h. After the digestion, non-digested materials were removed by ethanol precipitation. The supernatants were dried by a SpeedVac, and then dissolved in 20 μl buffer A [100 mM potassium phosphate (pH 7.0)]. The nucleosides were separated by reverse phase HPLC with ODS column (ultrasphere ODS, BECKMAN) eluting at a flow rate of 0.7 ml/min using sequential gradients of buffers A and B: 0–5 min 0% B. 5–20 min 0–15% B. 20–35 min 15–45% B. 35–60 min 45–100% B. 60–75 min 100–100% B [buffer B: 1 mM potassium phosphate (pH 7.0) and 90% methanol]. The concentration of each nucleoside was determined by monitoring A260 and integration using D-2500 Chromato-Integrator (Hitachi). To confirm the analogue peak, the digested products and each nucleoside analogue were co-eluted by HPLC.

Reverse transcription with HIV RT

Reverse transcription reaction by HIV reverse transcriptase was performed using RNA templates containing ho4C, mo4C, rP, sc4C or m4C. The heteroduplex template/primer was prepared by heating a 1:1 (100 nM) mixture of DNA primer 1 (5′-CGAATTGGGTACCGGGCCCC-3′) and RNA template in a buffer (5 μl) containing 50 mM Tris–HCl (pH 8.3), 50 mM KCl and 1% Nonidet P-40 at 70°C for 10 min, and cooling it slowly to room temperature. A reverse transcription reaction mixture (10 μl) containing 50 mM Tris–HCl (pH 8.3), 50 mM KCl, 1% Nonidet P-40, 10 mM MgCl2, 3 mM DTT, 0.5 mM dNTPs, 50 nM template/primer, 5 U RNase inhibitor and 2 μM HIV reverse transcriptase was incubated at 37°C for 1 h and then heated at 70°C for 10 min. After the reaction, the RT products were amplified by PCR. The PCR mixture (20 μl), which contained 10 mM Tris–HCl (pH 8.3), 50 mM KCl, 1.5 mM MgCl2, 0.2 mM dNTPs, 1 μM DNA primer 1, 1 μM DNA primer 2 (5′-AAAGCTGGAGCTCCACCGCG-3′), 1 μl RT products and 0.5 U Taq DNA polymerase, was reacted by sequential PCR program: 94°C 2 min [94°C 30 s, 55°C 1 min, 72°C 2 min] × 15 cycle. PCR roducts were purified on 2% agarose gel, and a part of the purified DNA was sequenced directly using a BigDye terminator v3.1 Cycle Sequencing Kit and an ABI PRISM 3100-Avant Genetic Analyzer (Applied Biosystems). The remaining cDNA was ligated into pBluescript II SK (−) after digestion by SacI and KpnI, and cloned in E.coli, and the integrated plasmid obtained from the bacteria were sequenced with ABI PRISM 3100-Avant Genetic Analyzer.

Reverse transcription with AMV RT

Reverse transcription reaction was also performed by AMV reverse transcriptase using RNA templates, which contained ho4C, mo4C, rP or sc4C in place of U, and m4C in place of C. RT–PCR mixtures (20 μl) contained 1× AMV/Tfl buffer (Promega), 1 mM MgSO4, 0.2 mM dNTPs, 1 μM DNA primer 1, 1 μM DNA primer 2, 2.5 nM RNA template, 1 U AMV reverse transcriptase and 1 U Tfl DNA polymerase. The mixtures were reacted by sequential RT–PCR program: 48°C 45 min, 94°C 2 min, [94°C 30 s, 60°C 1 min and 68°C 2 min] × 15 cycle. Then, the RT–PCR products were purified on 2% agarose gel and a part of the purified DNA was sequenced directly using a BigDye terminator v3.1 Cycle Sequencing Kit and an ABI PRISM 3100-Avant Genetic Analyzer (Applied Biosystems). The other cDNA was ligated into pBluescript II SK (−) after digestion by SacI and KpnI, cloned in E.coli, and sequenced with an ABI PRISM 3100-Avant Genetic Analyzer.

Steady-state kinetics

One base insertion reaction by HIV reverse transcriptase was performed using RNA templates containing ho4C, mo4C, rP or sc4C in place of U. In a buffer containing 50 mM Tris–HCl (pH 8.3), 50 mM KCl, 1% Nonidet P-40, 10 mM MgCl2 and 3 mM DTT, 32P-labelled DNA primer (50 nM) was annealed to the RNA template (75 nM) by heating at 90°C for 3 min and cooling slowly to room temperature. Ins-primer (5′-CCGGGCCCCCCCTCG-3′) was used for one base insertion opposite each analogue. ExtA-primer (5′-CCGGGCCCCCCCTCGA-3′) and ExtG-primer (5′-CCGGGCCCCCCCTCGG-3′) were used for extension from dA and dG, respectively, paired with the analogues. To the template-primer (7 μl), 50 nM HIV RT (1 μl) was added and pre-incubated at 37°C for 5 min. Each reaction was initiated by addition of 2 μl of 5× dNTP, and terminated by addition of 10 μl of loading buffer [90% formamide, 0.05% BPB and 50 mM EDTA (pH 8.0)]. The reaction products were analyzed by 7 M urea 20% denaturing PAGE. The gels were exposed to Imaging Plate and analyzed with Imaging Analyzer BAS-1800II (Fujifilm) to quantitate each band. The velocity of reaction was determined using the following equation: vrel = 100 I1 / (I0 + 0.5 I1) t, where I0 is intensity of the unextended band, I1 is intensity of the extended band and t is reaction time (36). The reaction time was chosen to be in the linear range. Graphs of rate versus dNTP concentration were analyzed using non-linear regression in KaleidaGraph 4.0 for the determination of Michaelis constant (Km) and relative maximum velocity (Vmax, rel). The frequency values of insertion (fins) and extension (fext) were defined by a ratio of Vmax, rel/Km for each base pair to Vmax, rel/Km for dA:U pair.

Transcription by human RNA polymerase II and the nearest-neighbor analysis

RNA transcription by human RNA polymerase II was performed using HeLa Nuclear Extract (Promega). A PCR product (1140 bp) containing CMV immediate early promoter and supF gene amplified from pCMV-supF plasmid was used as a template for runoff transcription. A standard reaction mixture (25 μl) contained 20 mM HEPES (pH 7.9), 100 mM KCl, 0.2 mM EDTA, 20% glycerol, 3 mM MgCl2, 0.4 mM ATP, CTP and UTP, 0.016 mM GTP, 450 ng DNA template, 40 U RNase inhibitor, 10 μCi [α-32P]GTP (3000 Ci/mmol) and 8 U HeLa nuclear extract. To study incorporation of the ribonucleoside triphosphate analogues, they were added in place of CTP or UTP. The mixtures were incubated at 30°C for 1 h. The transcripts were deproteinated with phenol/chloroform/isoamyl alcohol (25:24:1) extraction and purified with Centri-Sep spin column. The transcripts were separated by 7 M urea 5% denaturing polyacrylamide gel, and analyzed with Imaging Analyzer BAS-1800II (Fujifilm).

For the nearest-neighbor analysis, the RNA transcripts were digested in 10 μl of 15 mM sodium acetate (pH 4.5), 1.5% glycerol and 1 U RNase T2 at 37°C for 14 h. To the dried reaction mixtures, 0.25 A260 U of non-isotopic 2′, 3′-NMPs were added as standards, and the digests were analyzed by two-dimensional cellulose TLC (Funacel SF 10 × 10 cm) with the use of isobutyric acid/ammonia/water (66:1:33, v./v./v.) for the first dimension, and ammonium sulfate/0.1 M sodium phosphate (pH 6.8)/n-propanol (60:100:2, wt./v./v.) for the second dimension. The TLC plates were analyzed with Imaging Analyzer BAS-1800II (Fujifilm).

RESULTS

Incorporation of ribonucleotide analogues in transcription by T3 RNA polymerase

Incorporation of the 5′-triphosphates of the N4-modified cytidine analogues, ho4C, mo4C, m4C, rP and sc4C, into RNA by T3 RNA polymerase was examined. Transcription was performed using reaction mixtures where one of the four triphosphates was replaced by an analogue. RNA transcripts were produced when ho4CTP and mo4CTP were used in place of UTP, and when m4CTP was used in place of CTP. Other combinations, e.g. ho4CTP used in place of CTP, GTP or ATP, produced no RNA transcripts even if 10-fold excess concentration was added (data not shown). rPTP and sc4CTP were incorporated into the transcripts as a substitute of UTP as well as CTP (Supplementary Figure S2). HPLC analysis demonstrated that almost all uridine or cytidine in RNA was replaced by the analogues in transcription by T3 RNA polymerase as shown in Supplementary Table S1 and Supplementary Figure S3. These transcripts were then used as templates for reverse transcription. In addition to these cytidine analogues, the incorporation of the 5′-triphosphates of 3, N4-ethenocytidine, 9-(β-D-ribofuranosyl)-N6-methoxy-2,6-diaminopurine, 2-hydroxyadenosine, inosine and 8-bromoadenosine were studied, but these were not incorporated in place of any normal nucleotides in this assay (data not shown).

Templating properties of mutagenic cytidine analogues by reverse transcription

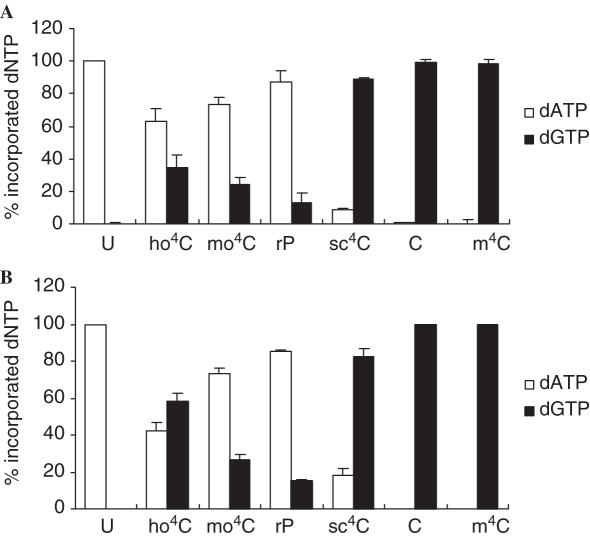

The RNA templates containing the N4-modified cytidine analogues were reverse-transcribed with HIV and AMV reverse transcriptases to produce cDNAs, which were amplified by PCR. The incorporation of native dNTPs opposite the analogues was examined by direct sequencing of the amplified cDNAs. In the direct sequencing electropherograms of the cDNA produced with HIV reverse transcriptase, every peak consists of a single line when the RNA template containing only natural nucleotides was used. However, C peaks accompany T peaks when the RNA templates contained ho4C, mo4C, rP or sc4C in place of U (Supplementary Figure S4a). From the RNA containing the various substrates, the average peak height ratios of C to T were 0.60 ± 0.06, 0.48 ± 0.03, 0.21 ± 0.02 and 7.2 ± 0.4 for cDNAs from ho4C-RNA, mo4C-RNA, rP-RNA and sc4C-RNA, respectively. AMV reverse transcriptase gave similar results (Supplementary Figure S4b). The average ratios of C peak height to T peak height were 0.75 ± 0.04, 0.43 ± 0.03, 0.27 ± 0.04 and 4.0 ± 0.5 for cDNAs from ho4C-RNA, mo4C-RNA, rP-RNA and sc4C-RNA, respectively. These ratios correspond to those of incorporated nucleotides opposite the analogues (data not shown). The mixed patterns in the electropherograms indicated that these analogues in RNA are mutagenic, causing ambiguous misincorporation by HIV and AMV reverse transcriptases. The RNA template containing m4C exhibited no such ambiguity.

Sequencing analyses after cloning (Figure 3 and Supplementary Table S2) gave similar results. The ratio of incorporated dGMP to dAMP opposite ho4C and rP was 0.57 and 0.15 for HIV reverse transcriptase and 1.4 and 0.17 for AMV reverse transcriptase, respectively. The G/A ratio for mo4C was approximately 0.35 for both reverse transcriptases. The G/A ratio for sc4C was 10.7 and 4.8 for HIV and AMV reverse transcriptase, respectively. Therefore, these analogues in RNA have the potential for inducing mutations at different rates. In contrast, dGMP was preferentially incorporated opposite m4C by both reverse transcriptases consistent with the results of the sequencing analyses on the cDNA without cloning.

Figure 3.

Rates of dATP and dGTP incorporated opposite cytidine analogues by HIV RT (A) and AMV RT (B). Incorporated dATP and dGTP were calculated from sequencing results of cloned cDNA. In this figure, averages and standard deviations were calculated from three independent experiments.

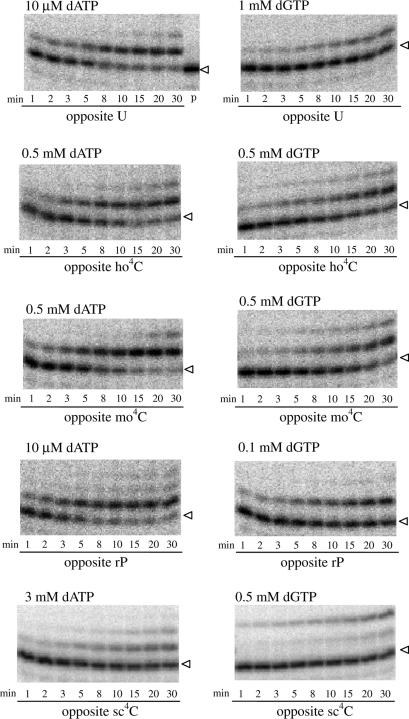

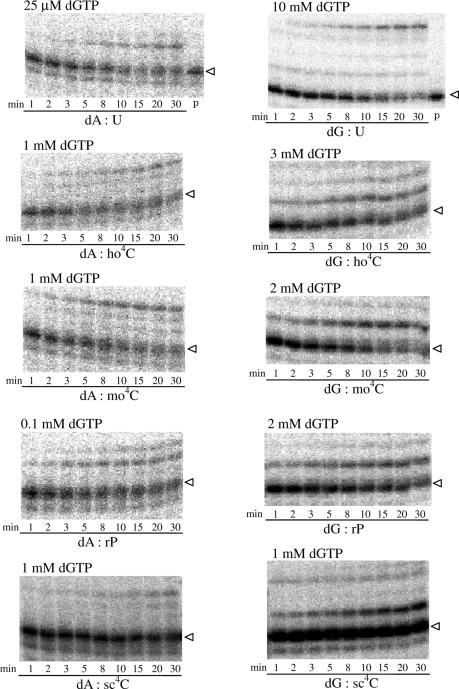

Steady-state kinetics of insertion opposite ribonucleotide analogues by HIV RT

To study the ambiguous incorporation opposite the analogues by HIV and AMV reverse transcriptases, the same template was annealed to a primer to initiate incorporation of dNTPs opposite the analogues (Figure 2 and Supplementary Figure S1). Figure 4 shows typical patterns of the primer extension. The steady-state Vmax and Km for the insertion of all four natural dNTPs opposite the N4-modified cytidine analogues in RNA template were determined. As a control reaction, the Vmax and Km for the RNA template containing uridine at the same position were measured. The observed values of kinetic data for each reaction are shown in Table 1. The Km for the incorporation of dA opposite U is about the same as a reported one (37). Among them, ho4C, mo4C and rP are shown to be highly ambiguous in their base pairing properties, consistent with the aforementioned sequencing analyses. However, ho4C and mo4C are different from rP in the mechanism that makes them mutagenic because ho4C and mo4C can adopt either syn or anti conformers, whilst rP is constrained in the anti conformation. In the syn conformation, the hydroxyl or methoxyl group protrudes into the hydrogen bonding face.

Figure 4.

Time course of insertion of dATP and dGTP opposite cytidine analogues. p: primer only.

Table 1.

Steady-state kinetics data for insertion opposite cytidine analogues, ho4C, mo4C, rP and sc4C in RNA templates by HIV RT

| T:P | Km (μM) | Vmax,rel (%/s) (× 10−2) | Vmax,rel/Km | fins |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| U:dA | 2.5 ± 0.5 | 15 ± 2 | 6.3(± 1.4) × 10−2 | 1 |

| U:dG | 59 ± 17 | 3.1 ± 0.3 | 5.4(± 1.0) × 10−4 | 8.8(± 1.6) × 10−3 |

| U:dC | 2038 ± 575 | 6.0 ± 1.3 | 3.1(± 1.0) × 10−5 | 5.0(± 1.3) × 10−4 |

| U:dT | 2680 ± 381 | 1.8 ± 0.4 | 6.8(± 0.7) × 10−6 | 1.1(± 0.2) × 10−4 |

| ho4C:dA | 70 ± 13 | 22 ± 1 | 3.2(± 0.6) × 10−3 | 5.1(± 0.4) × 10−2 |

| ho4C:dG | 62 ± 4 | 11 ± 2 | 1.7(± 0.4) × 10−3 | 2.8(± 0.5) × 10−2 |

| ho4C:dC | 1963 ± 1086 | 7.8 ± 1.7 | 4.5(± 1.4) × 10−5 | 7.5(± 3.0) × 10−4 |

| ho4C:dT | 2239 ± 807 | 11 ± 1 | 5.5(± 2.9) × 10−5 | 8.7(± 3.9) × 10−4 |

| mo4C:dA | 131 ± 15 | 20 ± 2 | 1.5(± 0.2) × 10−3 | 2.6(± 1.0) × 10−2 |

| mo4C:dG | 158 ± 75 | 9.8 ± 1.7 | 6.9(± 2.5) × 10−4 | 1.1(± 0.3) × 10−2 |

| mo4C:dC | 2742 ± 962 | 3.7 ± 0.8 | 1.5(± 0.8) × 10−5 | 2.3(± 0.9) × 10−4 |

| mo4C:dT | 3486 ± 477 | 5.8 ± 0.3 | 1.7(± 0.3) × 10−5 | 2.8(± 0.6) × 10−4 |

| rP:dA | 2.4 ± 0.2 | 26 ± 7 | 1.1(± 0.3) × 10−1 | 1.9 ± 0.7 |

| rP:dG | 15 ± 2 | 14 ± 2 | 9.7(± 3.2) × 10−3 | 1.6(± 0.6) × 10−1 |

| rP:dC | 1870 ± 296 | 7.6 ± 0.9 | 4.2(± 1.2) × 10−5 | 7.0(± 2.5) × 10−4 |

| rP:dT | 1730 ± 457 | 3.7 ± 0.3 | 2.3(± 0.8) × 10−5 | 3.7(± 1.2) × 10−4 |

| sc4C:dA | 234 ± 21 | 5.3 ± 1.3 | 2.3(± 0.7) × 10−4 | 3.9(± 2.0) × 10−3 |

| sc4C:dG | 5.0 ± 0.7 | 3.1 ± 0.0 | 6.3(± 0.8) × 10−3 | 1.0(± 0.3) × 10−1 |

| C:dG | 1.7 ± 0.9 | 6.0 ± 0.8 | 3.8(± 1.2) × 10−2 |

No extended products from sc4C:dC and sc4C:dT.

The fins values of dGTP opposite ho4C and mo4C were about the same as insertion of dGTP opposite U. However, the values of dATP insertion opposite ho4C and mo4C were 20 and 42-fold smaller than opposite U, respectively. Thus, the insertion ratio of dGTP to dATP opposite ho4C and mo4C were about 50-fold higher than opposite U. In contrast, the fins value of dGTP opposite rP was 18-fold higher than opposite U, but the value of dATP was only 2-fold higher than opposite U. Therefore, the insertion ratio of dGTP to dATP opposite rP was 10-fold higher than opposite U.

Steady-state kinetics of extension of ribonucleotide analogues pair by HIV RT

The other important factor to affect the yields of the mutated cDNA is the efficiency of extension from the nucleotides incorporated opposite the analogues. For this purpose, primers longer by 1 nt than those for the insertion study were annealed so that their dA, or dG at 3′-terminus could pair with the analogues (Figure 2 and Supplementary Figure S1). The steady-state Vmax and Km for the extension from dA or dG with the N4-modified cytidine analogues in RNA templates were determined from the time course experiments (Figure 5) using the template-primers. The observed values of kinetic data for each reaction are shown in Table 2. To compare the efficiency of extension from each base pair, the frequency values of extension (fext) were defined as the ratio of catalytic efficiency (Vmax/Km) for each reaction.

Figure 5.

Extension from nucleotides incorparated opposite cytidine analogues. p: primer only.

Table 2.

Steady-state kinetics data for extension from dA or dG paired with a cytidine analogue, ho4C, mo4C, rP or sc4C by HIV RT

| T:P | Km (μM) | Vmax,rel (%/s) (×10−2) | Vmax,rel/Km | fext |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| U:dA | 0.17 ± 0.04 | 4.3 ± 0.2 | 2.6(± 0.4) × 10−1 | 1 |

| ho4C:dA | 2.6 ± 0.2 | 8.5 ± 0.1 | 3.3(± 0.2) × 10−2 | 1.3(± 0.3) × 10−1 |

| mo4C:dA | 2.9 ± 1.1 | 10 ± 2 | 3.7(± 0.8) × 10−2 | 1.5(± 0.5) × 10−1 |

| rP:dA | 0.18 ± 0.04 | 6.7 ± 0.1 | 3.8(± 0.7) × 10−1 | 1.5 ± 0.5 |

| sc4C:dA | 4.6 ± 1.8 | 1.5 ± 0.2 | 3.5(± 1.2) × 10−3 | 1.3(± 0.3) × 10−2 |

| U:dG | 1600 ± 494 | 14 ± 3 | 9.2(± 1.9) × 10−5 | 3.6(± 0.9) × 10−4 |

| ho4C:dG | 166 ± 7 | 17 ± 1 | 1.0(± 0.1) × 10−3 | 3.8(± 0.8) × 10−3 |

| mo4C:dG | 162 ± 29 | 18 ± 1 | 1.1(± 0.1) × 10−3 | 4.3(± 0.8) × 10−3 |

| rP:dG | 149 ± 6 | 15 ± 1 | 1.0(± 0.1) × 10−3 | 3.9(± 1.0) × 10−3 |

| sc4C:dG | 48 ± 15 | 2.6 ± 0.04 | 5.9(± 2.1) × 10−4 | 2.4(± 1.3) × 10−3 |

| C:dG | 72 ± 14 | 10 ± 1 | 1.5(± 0.4) × 10−3 |

The extension from dA paired with ho4C and mo4C occurred 7-fold less efficiently than for the dA:U pair. The extension frequency of dA:sc4C pair was 78-fold lower than dA:U pair. In contrast, the fext value of dA:rP pair was similar to dA:U pair. The fext values of dG paired with ho4C, mo4C and rP were about the same as each other and 10-fold higher than the values of dG:U pair. The fext value of dG:sc4C pair was slightly lower than the other analogues paired with dG. The extension from dG pair occurred 2945-fold less frequently than dA pair when paired with U. The extension frequencies of dG pair were 33, 34, 376 and 7-fold lower than dA pair when paired with ho4C, mo4C, rP and sc4C, respectively. Consequently, dG pairs were extended less frequently than dA pairs, but the extension ratio of dG pair to dA pair was higher when paired with these analogues. It is also notable that the lower extension from dG may not indicate instability of the dG-analogue pairs, because dG paired with cytidine also showed a lower extension frequency compared to dA paired with uridine.

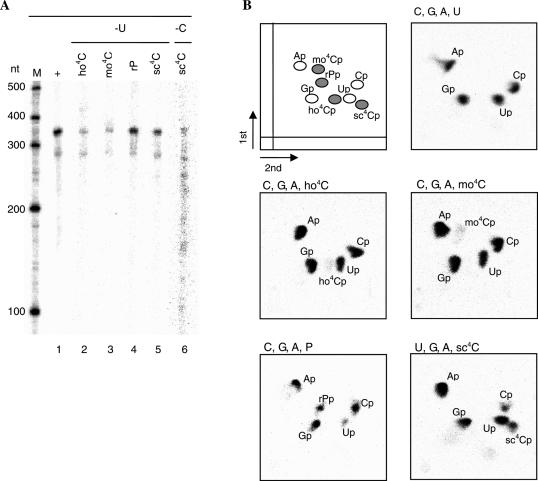

Incorporation of ribonucleotide analogues in transcription by human RNA polymerase II

In this study, we have analyzed the templating properties of N4-cytidine analogues in RNA during reverse transcription by HIV RT. It is important to know whether they can be incorporated into RNA by human RNA polymerase II. This was examined by nearest-neighbor analysis of the products of transcription reaction using HeLa nuclear extract in the presence of [α-32P]GTP and the N4-cytidine analogues. Following transcription, the transcripts were digested to nucleoside 3′-monophosphates, which were separated by two-dimensional TLC. Radioactive spots corresponding to the analogues were observed when ho4CTP, mo4CTP and rPTP were used in place of UTP and sc4CTP in place of CTP (Figure 6). From the intensities of the spots, the amount of incorporated ho4Cp, mo4Cp, rPp and sc4Cp were calculated to be 3.6, 3.6, 12 and 12% of total nucleotides in synthesized transcripts, respectively (Table 3). Up and Cp derived from UTP and CTP, which were not added to the reaction, were also detected possibly due to presence of small amounts of the triphosphates in the extract. When UTP and CTP were added at 20% of the concentration of rPTP and sc4CTP, the spots of the rPp and sc4Cp were detected, and expected products were formed (Supplementary Figure S5).

Figure 6.

Incorporation of cytidine analogues with HeLa nuclear extract. The transcripts were analyzed by denaturing 5% polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis. Above each lane, rNTP added to the extract are recorded. Molar ratios of ATP:(32P-)GTP:CTP:UTP:C*TP is 1:0.04:1:1:1 if present (A). Two-dimensional cellulose TLC for nearest-neighbor analyses of the transcripts (B). In the transcription, the CTP analogues, ho4CTP, mo4CTP and rPTP, respectively, were added in place of UTP, while sc4CTP was added in place of CTP.

Table 3.

Nucleotide composition of the transcripts with HeLa nuclear extract in the presence of cytidine analogues

| Reaction | Number of nucleotides nearest to GMP | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ap | Gp | Cp | Up | C*p | |

| Urxn | 22.7 ± 1.5 | 20.6 ± 0.4 | 19.9 ± 0.2 | 17.8 ± 1.6 | |

| ho4Crxn | 25.1 ± 1.5 | 20.2 ± 0.8 | 18.3 ± 2.0 | 14.5 ± 1.4 | 2.9 ± 0.2 |

| mo4Crxn | 25.4 ± 1.6 | 19.0 ± 0.4 | 16.3 ± 2.3 | 17.4 ± 1.4 | 2.9 ± 0.8 |

| rPrxn | 27.8 ± 0.3 | 19.4 ± 1.6 | 18.5 ± 1.2 | 5.6 ± 0.1 | 9.7 ± 0.7 |

| sc4Crxn | 29.4 ± 1.7 | 16.8 ± 1.1 | 5.9 ± 1.1 | 19.3 ± 1.4 | 9.5 ± 0.2 |

| rP/1/5/Urxn | 29.0 ± 2.8 | 18.9 ± 0.4 | 18.9 ± 0.7 | 12.0 ± 1.6 | 1.8 ± 0.2 |

| sc4C/1/5Crxn | 28.0 ± 1.3 | 18.7 ± 0.7 | 17.3 ± 0.7 | 15.7 ± 1.3 | 1.3 ± 0.1 |

In the control reaction (Urxn), ATP, CTP, 32P-GTP and UTP at the molar ratio of 1:1:0.2:1 were added to the extract. In ho4Crxn, mo4Crxn, and rPrxn, the CTP analogues, ho4CTP, mo4CTP and rPTP, respectively, were added in place of UTP, while sc4CTP was added in place of CTP. In P/1/5/Urxn and sc4C/1/5Crxn, molar ratios of ATP, CTP, GTP, UTP and rPTP and sc4CTP were 1:1:0.2:0.2:1 and 1:0.2:0.2:1, respectively. The numbers of nucleotides 5′ to G were determined via the following equation: (radioactivity of each nucleotide)/(total radioactivity of all nucleotides) × [81 (total numbers of nucleotides at 5′ neighbor of G)]. The theoretical numbers of nucleotides are Ap = 25, Gp = 21, Cp = 23 and Up = 12.

DISCUSSION

In this study, we have investigated the templating properties of ribonucleotide analogues, ho4C, mo4C, m4C, sc4C and rP in reverse transcription for an assessment of their mutagenic potentials for the development of antiviral drugs. Ribonucleotides might be more suitable for this purpose than deoxyribonuclotides because they are less likely to disturb the host genetic machinery. In the present study, three N4-oxy, one N4-amino and one N4-alkylcytidine derivatives were examined. N4-modified cytidine analogues contain the most potent nucleoside analogue mutagens (27,38). Results of the sequencing analysis of cDNA products indicated that substitution of U by ho4C, mo4C, rP and sc4C directs the incorporation of both dA and dG, suggesting their ability to induce U-to-C mutations.

N4-oxycytidines exist preferentially as the imino tautomer (ratio 9:1) (22–24,28,29,39–42), which results in base pairing with dA. As expected, rP, ho4C and mo4C preferred the incorporation of dA. However, the ratio of dG to dA opposite ho4C and mo4C was higher than expected from their base pairing ability.

In order to examine the mechanism of the incorporation further, we analyzed steady-state kinetics for insertion opposite each analogue and extension from dA or dG paired with each analogue. We found that dAMP insertion opposite ho4C and mo4C was less efficient than opposite U, while dGMP was incorporated in a similar efficiency opposite ho4C, mo4C and U. Thus, the incorporation of dGMP/dAMP opposite the analogues increased. In contrast, an increase in the insertion of dGMP with unchanged incorporation of dAMP caused the increase in the dGMP/dAMP opposite rP. The decrease in the insertion of dATP opposite ho4C and mo4C can be explained by the fact that the N4-hydroxy or N4-methoxy group prefers the syn conformation, which interferes with hydrogen bonding in a Watson–Crick base pair (40–42). On the other hand, the insertion of dATP opposite rP and U was of the same order and the ratio of dATP and dGTP inserted opposite rP was similar to the ratio of its imino and amino tautomers (29). This suggests that the imino and amino tautomers of rP behave like natural U and C, because the N4-hydroxyl group is constrained in an anti-form away from the hydrogen bonding face enabling hydrogen bonding by Watson–Crick base pairing (43,44).

The extension frequencies from dA and dG paired with N4-oxy-cytidine analogues also show an interesting feature. The extension frequency from dA:rP pair was 10-fold higher than those from dA:ho4C pair and dA:mo4C pair, while the frequencies from dG were identical. This is clearly due to the preference for the syn-configuration in the imino-forms of ho4C and mo4C. It interferes with Watson–Crick pairing with dA, but can pair with dG through the wobble-type conformation (45), which possibly changes to Watson–Crick base pairing with a transition to the amino-form (46) after its incorporation. From the latter base pair the chain could extend efficiently. It should also be noted that the G/A ratio of incorporation opposite analogues should depend upon the dGTP/dATP ratio, but the extension from G-analogue pair should depend solely upon the concentration of dGTP, which will be incorporated opposite C next to the analogue. The concentrations of all the dNTPs used in our experiments of cDNA synthesis were higher than the Km for dG paired with the analogues, but lower than the Km for dG mismatched with uridine. Therefore, the dNTP concentration would be sufficient to extend from dG paired with the analogues, but not uridine. Thus this selection step may efficiently compliment the low fidelity insertion step to avoid the errors in cDNA synthesis from normal RNA, but it may not in the synthesis from RNA containing analogues.

N4-aminocytidine derivatives are also highly mutagenic analogues with tautomeric ambiguity in their structures (25,47). N4-aminocytidine derivatives exist preferentially in the amino tautomeric form (28,48), and our results are consistent with this. We examined here sc4C, an N4-aminocytidine derivative, which directs the incorporation of both dGMP and dAMP but with a preference for dGMP. N4-alkylated cytidine, N4-methylcytidine behaves as cytidine only. Although we need to examine other conditions, N4-modification without tautomerism does not seem to affect incorporation. These facts suggested that a cytidine analogue that has equal amino and imino tautomers and prefers the anti conformation, were such an analogue available, would be more mutagenic and a useful nucleotide as an antiviral drug as we have described.

The ribonucleotide analogues need to be incorporated into RNA by the host RNA polymerase II to induce mutations into the retroviral genome. One option would be to use the nucleoside analogues and then to rely on the host cellular processes to convert the nucleosides to the active triphosphate substrates, though at this stage we do not know whether the nucleosides are substrates for cellular kinases. We examined the incorporation of the analogue triphosphates by human RNA polymerase II; the results suggest that ho4CTP, mo4CTP and rPTP are incorporated in place of UTP, and sc4CTP is incorporated in place of CTP. rPTP and sc4CTP are more efficiently incorporated into RNA than ho4CTP and mo4CTP. It should be noted that whilst the experiments described here use relatively high concentrations of analogue triphosphates, in a therapeutic sense it would be feasible to use lower concentrations. This is because a relatively low mutation frequency will lead to error catastrophe with the virus, and because the mutations can build up over successive rounds of replication.

We have examined a series of potentially mutagenic cytidine analogues with the view that these might induce error catastrophe if incorporated into viral genomic RNA. The data supports the view that certain of the analogues examined induce mutations both by misincorporation into RNA and by reverse transcription. From the results mentioned above, these analogues except for m4C may induce mutations in the retroviral genome if present as triphosphates. At present the analogues described here have not been assayed as antiviral agents. To apply the nucleosides as antiretroviral drugs, the nucleosides need to pass through the cell membrane, and to be phosphorylated by cellular kinases for generation the active triphosphates. To bypass the kinase step, liposomal-based drug delivery methods may be available to transport the 5′-triphosphate into the cell (49,50). Phosphorylated pronucleotides (masked phosphate analogues) may also useful (51,52). By using these methods, we could deliver the phosphorylated analogues into the cell; induce mutations in retroviruses, leading to error catastrophe. Intracellular pyrimidine concentrations are generally much lower than purine concentrations (53) the latter are implicated in important cellular processes, such as metabolic process and signaling besides DNA and RNA synthesis. Thus, use of mutagenic pyrimidine analogues might be more effective, and result in less adverse cellular effects. Additionally, it will be possible to improve the therapeutic efficacy by combinations of mutagenic nucleoside and antiviral inhibitor (54–57). Further work would be required to determine the antiviral efficacy of these analogues, but we have provided evidence to support the fact that if incorporated into viral RNA the analogues could lead to lethal mutagenesis.

SUPPLEMENTARY DATA

Supplementary Data are available at NAR Online.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by a Grant-in-Aid for Scientific Research (C) (No. 17590060) from Japan Society for the Promotion of Science. Funding to pay the Open Access publication charges for this article was provided by Japan Society for the Promotion of Science.

Conflict of interest statement. None declared.

REFERENCES

- 1.Ho D.D., Neumann A.U., Perelson A.S., Chen W., Leonard J.M., Markowitz M. Rapid turnover of plasma virions and CD4 lymphocytes in HIV-1 infection. Nature. 1995;373:123–126. doi: 10.1038/373123a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Coffin J.M. HIV population dynamics in vivo: implication for genetic variation, pathogenesis, and therapy. Science. 1995;267:483–489. doi: 10.1126/science.7824947. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Domingo E. Viruses at the edge of adaptation. Virology. 2000;270:251–253. doi: 10.1006/viro.2000.0320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Crotty S., Cameron C.E., Andino R. RNA virus error catastrophe: direct molecular test by using ribavirin. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2001;98:6895–6900. doi: 10.1073/pnas.111085598. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Graci J.D., Cameron C.E. Quasispecies, error catastrophe, and the antiviral activity of ribavirin. Virology. 2002;298:175–180. doi: 10.1006/viro.2002.1487. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Loeb L.A., Essigmann J.M., Kazazi F., Zhang J., Rose K.D., Mullins J.I. Lethal mutagenesis of HIV with mutagenic nucleoside analogs. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 1999;96:1492–1497. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.4.1492. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cameron C.E., Castro C. The mechanism of action of ribavirin: lethal mutagenesis of RNA virus genomes mediated by the viral RNA-dependent RNA polymerase. Curr. Opin. Infect. Dis. 2001;14:757–764. doi: 10.1097/00001432-200112000-00015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Crotty S., Maag D., Arnold J.J., Zhong W., Lau J.Y.N., Hong Z., Andino R., Cameron C.E. The broad-spectrum antiviral ribonucleoside ribavirin is an RNA virus mutagen. Nature Med. 2000;6:1375–1379. doi: 10.1038/82191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Severson W.E., Schmaljohn C.S., Javadian A., Jonsson C.B. Ribavirin causes error catastrophe during Hantaan virus replication. J. Virol. 2003;77:481–488. doi: 10.1128/JVI.77.1.481-488.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Holland J.J., Domingo E., de la Torre J.C., Steinhauer D.A. Mutation frequencies at defined single codon sites in vesicular stomatitis virus and poliovirus can be increased only slightly by chemical mutagenesis. J. Virol. 1990;64:3960–3962. doi: 10.1128/jvi.64.8.3960-3962.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sierra S., Davila M., Lowenstein P.R., Domingo E. Response of foot-and-mouth disease virus to increased mutagenesis: Influence of viral load and fitness in loss of infectivity. J. Virol. 2000;74:8316–8323. doi: 10.1128/jvi.74.18.8316-8323.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Grande-Pérez A., Sierra S., Castro M.G., Domingo E., Lowenstein P.R. Molecular indetermination in the transition to error catastrophe: systematic elimination of lymphocytic choriomeningitis virus through mutagenesis does not correlate linearly with large increases in mutant spectrum complexity. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2002;99:2938–2943. doi: 10.1073/pnas.182426999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ruiz-Jarabo C.M., Ly C., Domingo E., de la Torre J.C. Lethal mutagenesis of the prototypic arenavirus lymphocytic choriomeningitis virus (LCMV) Virology. 2003;308:37–47. doi: 10.1016/s0042-6822(02)00046-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Harris K.S., Brabant W., Styrchak S., Gall A., Daifuku R. KP-1212/1461, a nucleoside designed for the treatment of HIV by viral mutagenesis. Antiviral Res. 2005;67:1–9. doi: 10.1016/j.antiviral.2005.03.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ross J. Control of messenger RNA stability in higher eukaryotes. Trends Genet. 1996;12:171–175. doi: 10.1016/0168-9525(96)10016-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Heintz N., Sive H.L., Roeder R.G. Regulation of human histone gene expression: kinetics of accumulation and changes in the rate of synthesis and in the half-lives of individual histone mRNAs during the HeLa cell cycle. Mol. Cell. Biol. 1983;3:539–550. doi: 10.1128/mcb.3.4.539. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bowie J.U., Reidhaar-Olson J.F., Lim W.A., Sauer R.T. Deciphering the message in protein sequences: tolerance to amino acid substitutions. Science. 1990;247:1306–1310. doi: 10.1126/science.2315699. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Guo H.H., Choe J., Loeb L.A. Protein tolerance to random amino acid change. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2004;101:9205–9210. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0403255101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Patel P.H., Loeb L.A. DNA polymerase active site is highly mutable: evolutionary consequences. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2000;97:5095–5100. doi: 10.1073/pnas.97.10.5095. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Loeb L.A., Mullins J.I. Lethal mutagenesis of HIV by mutagenic ribonucleoside analogs. AIDS Res. Hum. Retroviruses. 2000;16:1–3. doi: 10.1089/088922200309539. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Moriyama K., Otsuka C., Loakes D., Negishi K. Highly efficient random mutagenesis in transcription-reverse-transcription cycles by a hydrogen bond ambivalent nucleoside 5′-triphosphate analogue: potential candidates for a selective anti-retroviral therapy. Nucleosides Nucleotides Nucleic Acids. 2001;20:1473–1483. doi: 10.1081/NCN-100105242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Singer B., Spengler S. Ambiguity and transcriptional errors as a result of modification of exocyclic amino groups of cytidine, guanosine, and adenosine. Biochemistry. 1981;20:1127–1132. doi: 10.1021/bi00508a013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Singer B., Frank-Conrat H., Abbott L.G., Spengler S.J. N4-Methoxydeoxycytidine triphosphate is in the imino tautomeric form and substitutes for deoxythymidine triphosphate in primed poly d[A-T] synthesis with E.coli DNA polymerase I. Nucleic Acids Res. 1984;12:4609–4619. doi: 10.1093/nar/12.11.4609. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Reeves S.T., Beattie K.L. Base-pairing properties of N4-methoxydeoxycytidine 5′-triphosphate during DNA synthesis on natural templates, catalyzed by DNA polymerase I of Escherichia coli. Biochemistry. 1985;24:2262–2268. doi: 10.1021/bi00330a021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Negishi K., Takahashi M., Yamashita Y., Nishizawa M., Hayatsu H. Mutagenesis by N4-aminocytidine: induction of AT to GC transition and its molecular mechanism. Biochemistry. 1985;24:7273–7278. doi: 10.1021/bi00346a038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Takahashi M., Nishizawa M., Negishi K., Hanaoka F., Yamada M., Hayatsu H. Induction of mutation in mouse FM3A cells by N4-aminocytidine-mediated replicational errors. Mol. Cell. Biol. 1988;8:347–352. doi: 10.1128/mcb.8.1.347. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Moriyama K., Okada T., Negishi K. In: Recent Research Developments in Organic and Bioorganic Chemistry. Loakes D., editor. Vol. 5. 2002. pp. 152–161. Transworld Research Network, Kerala. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Brown D., Hewlins M., Schell P. The tautomeric state of N(4)-hydroxy- and N(4)-amino-cytosine derivatives. J. Chem. Soc. 1968;15:1925–1929. doi: 10.1039/j39680001925. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Harris V.H., Smith C.L., Cummins W.J., Hamilton A.L., Adams H., Dickman M., Hornby D.P., Williams D.M. The effect of tautomeric constant on the specificity of nucleotide incorporation during DNA replication: support for the rare tautomer hypothesis of substitution mutagenesis. J. Mol. Biol. 2003;326:1389–1401. doi: 10.1016/s0022-2836(03)00051-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Grice S.F.L., Gruninger-Leitch F. Rapid purification of homodimer and heterodimer HIV-1 reverse transcriptase by metal chelate affinity chromatography. Eur. J. Biochem. 1990;187:307–314. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1990.tb15306.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Budowsky E.I., Sverdlov E.D., Spasokukotskaya T.N. Mechanism of the mutagenic action of hydroxylamine VII. Functional activity and specificity of cytidine triphosphate modified with hydroxylamine and O-methylhydroxylamine. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 1972;287:195–210. doi: 10.1016/0005-2787(72)90370-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Shapiro R., Weisgras J.M. Bisulfite-catalyzed transamination of cytosine and cytidine. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 1970;40:839–843. doi: 10.1016/0006-291x(70)90979-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hayatsu H. Reaction of cytidine with semicarbazide in the presence of bisulfite. A rapid modification specific for single-stranded polynucleotide. Biochemistry. 1976;15:2677–2682. doi: 10.1021/bi00657a030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Moriyama K., Negishi K., Briggs M.S., Smith C.L., Hill F., Churcher M.J., Brown D.M., Loakes D. Synthesis and RNA polymerase incorporation of the degenerate ribonucleotide analogue rPTP. Nucleic Acids Res. 1998;26:2105–2111. doi: 10.1093/nar/26.9.2105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Eadie J., McBride L., Efcavitch J., Hoff L., Cathcart R. High-performance liquid chromatographic analysis of oligodeoxyribonucleotide base composition. Anal. Biochem. 1987;165:442–447. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(87)90294-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Petruska J., Goodman M.F., Boosalis M.S., Sowers L.C., Cheong C., Tinoco I., Jr Comparison between DNA melting thermodynamics and DNA polymerase fidelity. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 1988;85:6252–6256. doi: 10.1073/pnas.85.17.6252. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Yu H., Goodman M.F. Comparison of HIV-1 and avian virus reverse transcriptase fidelity on RNA and DNA templates. J. Biol. Chem. 1992;267:10888–10896. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Negishi K., Bessho T., Hayatsu H. Nucleoside and nucleobase analog mutagens. Mutat. Res. 1994;318:227–238. doi: 10.1016/0165-1110(94)90016-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Meervelt L.V., Lin P.K.T., Brown D.M. 6-(3,5-Di-O-acethyl-β-D-2-deoxyribofuranosyl)-3,4-dihydro-8H-pyrimido[4,5-c][1,2]-oxazin-7(6H)-one. Acta. Crystallogr. sect. C. 1995;51:1347–1350. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Les A., Adamowicz L., Rode W. Structure and conformation of N4-hydroxycytosine and N4-hydroxy-5-fluorocytosine. A theoretical ab initio study. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 1993;1173:39–48. doi: 10.1016/0167-4781(93)90240-e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Meervelt L.V. Structure of 3′,5′-Di-O-acetyl-N4-methoxycytosine. Acta. Crystallogr. sect. C. 1991;47:2635–2637. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Shugar D., Huber C., Birnbaum G. Mechanism of hydroxylamine mutagenesis. Crystal structure and conformation of 1,5-dimethyl-N4-hydroxycytosine. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 1976;447:274–284. doi: 10.1016/0005-2787(76)90050-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Stone M.J., Nedderman A.N., Williams D.H., Lin P.K.T., Brown D.M. Molecular basis for methoxyamine initiated mutagenesis: 1H nuclear magnetic resonance studies of base-modified oligodeoxynucleotides. J. Mol. Biol. 1991;222:711–723. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(91)90507-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Nedderman A.N.R., Stone M.J., Williams D.H., Lin P.K.T., Brown D.M. Molecular basis for methoxyamine-initiated mutagenesis: 1H nuclear magnetic resonance studies of oligodeoxynucleotide duplexes containing base-modified cytosine residues. J. Mol. Biol. 1993;230:1068–1076. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1993.1219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Hossain M.T., Chatake T., Hikima T., Tsunoda M., Sunami T., Ueno Y., Matsuda A., Takenaka A. Crystallographic studies on damaged DNAs:III. N4-methoxycytosine can form both Watson–Crick type and wobbled base pars in a B-form duplex. J. Biochem. 2001;130:9–12. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.jbchem.a002967. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Fazakerley G.V., Gdaniec Z., Sowers L.C. Base-pair induced shifts in the tautomeric equilibrium of a modified DNA base. J. Mol. Biol. 1993;230:6–10. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1993.1119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Nomura A., Negishi K., Hayatsu H., Kuroda Y. Mutagenicity of N4-aminocytidine and its derivatives in Chinese hamster lung V79 cells. Incorporation of N4-aminocytosine into cellular DNA. Mutat. Res. 1987;177:283–287. doi: 10.1016/0027-5107(87)90012-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Aida M., Negishi K., Hayatsu H., Maeda M. Ab initio molecular orbital study of the mispairing ability of a nucleotide base analogue, N4-aminocytosine. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 1988;153:552–557. doi: 10.1016/s0006-291x(88)81130-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Oussoren C., Magnani M., Fraternale A., Casabianca A., Chiarantini L., Ingebrigsten R., Underberg W., Storm G. Liposomes as carriers of the antiretroviral agent dideoxycytidine-5′-triphosphate. Int. J. Pharm. 1999;180:261–270. doi: 10.1016/s0378-5173(99)00016-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Zelphati O., Degols G., Loughrey H., Leserman L., Pompon A., Puech F., Maggio A., Imbach J., Gosselin G. Inhibition of HIV-1 replication in cultured cells with phosphorylated dideoxyuridine derivatives encapsulated in immunoliposomes. Antiviral Res. 1993;21:181–195. doi: 10.1016/0166-3542(93)90027-g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Wagner C.R., Iyer V.V., McIntee E.J. Pronucleotides: toward the in vivo delivery of antiviral and anticancer nucleotides. Med. Res. Rev. 2000;20:417–451. doi: 10.1002/1098-1128(200011)20:6<417::aid-med1>3.0.co;2-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Prang K., Wiebe L., Knaus E. Novel approaches for designing 5′-O-ester prodrugs of 3′-azido-2′, 3′-dideoxythymidine (AZT) Curr. Med. Chem. 2000;7:995–1039. doi: 10.2174/0929867003374372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Traut T. Physiological concentrations of purines and pyrimidines. Mol. Cell. Biochem. 1994;140:1–22. doi: 10.1007/BF00928361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Pariente N., Sierra S., Airaksinen A. Action of mutagenic agents and antiviral inhibitors on foot-and-mouth disease virus. Virus Res. 2005;107:183–193. doi: 10.1016/j.virusres.2004.11.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Pariente N., Sierra S., Lowenstein P.R., Domingo E. Efficient virus extinction by combinations of a mutagen and antiviral inhibitors. J. Virol. 2001;75:9723–9730. doi: 10.1128/JVI.75.20.9723-9730.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Pariente N., Airaksinen A., Domingo E. Mutagenesis versus inhibition in the efficiency of extinction of foot-and-mouth disease virus. J. Virol. 2003;77:7131–7138. doi: 10.1128/JVI.77.12.7131-7138.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Gerrish P.J., García-Lerma J.G. Mutation rate and the efficacy of antimicrobial drug treatment. Lancet Infect. Dis. 2003;3:28–32. doi: 10.1016/s1473-3099(03)00485-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.