Abstract

LFA-1 (αLβ2) mediates cell-cell and cell-extracellular matrix adhesions essential for immune and inflammatory responses. One critical mechanism regulating LFA-1 activity is the conformational change of the ligand-binding αL I domain from low-affinity (LA), closed form, to the high-affinity (HA), open form. Most known integrin antagonists bind both forms. Antagonists specific for the HA αL I domain have not been described. Here, we report the identification and characterization of a human antibody AL-57, which binds to the αL I domain in a HA but not LA conformation. AL-57 was discovered by selection from a human Fab-displaying library using a locked-open HA I domain as target. AL-57 Fab-phage bound HA I domain-expressing K562 cells (HA cells) in a Mg2+-dependent manner. AL-57 IgG also bound HA cells and PBMCs, activated by Mg2+/EGTA, PMA, or DTT. The binding profile of AL-57 IgG on PBMCs was the same as that of ICAM-1, the main ligand of LFA-1. In contrast, an anti-αL murine mAb MHM24 did not distinguish between the HA and LA forms. Moreover, AL-57 IgG blocked ICAM-1 binding to HA cells with a potency greater than MHM24. It also inhibited ICAM-1 binding to PBMCs, blocked adhesion of HA cells to keratinocytes, and inhibited PHA-induced lymphocyte proliferation with potencies comparable with MHM24. These results indicate that specifically targeting the HA I domain is sufficient to inhibit LFA-1-mediated, adhesive functions. AL-57 represents a therapeutic candidate for treatment of inflammatory and autoimmune diseases.

Keywords: integrin, I domain, ICAM-1, phage display, cell adhesion

INTRODUCTION

Integrins, a family of αβ heterodimeric transmembrane glycoproteins, are major adhesion receptors that mediate cell-cell and cell-extracellular matrix interactions. LFA-1 (αLβ2, CD11a/CD18) is a leukocyte-specific receptor belonging to the β2 integrin family (reviewed in ref. [1]). It consists of two noncovalently linked subunits, αL (CD11a) and β2 (CD18). The extracellular domain of the αL subunit contains a seven-bladed β-propeller domain, in which an ~200 amino acid sequence, the I domain, is inserted between Blades 2 and 3 [1]. The I domain, which is the putative ligand-binding site, contains a metal ion-dependent adhesion site (MIDAS), which upon binding with a metal ion, mediates ligand binding. The ligands for LFA-1 are ICAMs, including ICAM-1, ICAM-2, and ICAM-3, which are members of the Ig superfamily and are expressed on a wide variety of somatic cells [2, 3]. ICAM-1 is the most biologically important ligand and is highly inducible on APC and endothelial cells in response to inflammatory cytokines [4].

Through its interaction with ligands, LFA-1 regulates a range of immune functions, including T cell activation upon antigen recognition, T cell-mediated cytotoxicity, and leukocyte trafficking [1, 5, 6]. As a result of its critical role in inflammatory and immune responses, LFA-1 is implicated in the development of diseases such as psoriasis [7] and arthritis [8]. Efalizumab (Raptiva, Genentech, Inc., San Francisco, CA), an anti-CD11a antibody humanized from a murine mAb MHM24, has been approved for the treatment of chronic-moderate to severe plaque psoriasis (reviewed in ref. [9]).

The activity of LFA-1 is tightly controlled by conformational changes in the I domain [10–15]. On resting leukocytes, LFA-1 is maintained in an inactive, low-affinity (LA) form and becomes activated with high affinity (HA) for its ligands following stimulation [16]. Such conformational change and subsequently, enhanced affinity for ligand are mediated by the process of inside-out signaling, initiated by intracellular signals, following cellular activation, and transmitted from cytoplasmic to extracellular domains [17, 18]. It is proposed that inside-out signaling triggers a switchblade-like opening that extends the integrin headpiece away from the plasma membrane, resulting in conformational changes of the I domain and increased affinity for ligand binding [19].

Structures of I domains in the α subunits of integrins reveal two different conformations: open and closed [1, 20–22]. The αL I domain has been locked in the open or closed conformation with engineered disulfide bonds [11, 13–15]. Locking the αL I domain in the open conformation causes a 9000-fold increase in affinity for ICAM-1 compared with the affinity of the inactive wild-type I domain and the locked-closed conformation and can be reversed by disulfide reduction [15]. The binding to ICAM-1 is completely Mg2+-dependent. The affinity and kinetics of the locked-open I domain for ICAM-1 are comparable with that determined previously for the activated αLβ2 complex [23], indicating that the αL I domain, when locked in an open conformation, is sufficient for maximal affinity-binding to ICAM-1 [15]. When expressed on the cell surface, the locked-open I domain mediates cell adhesion as potently as maximally activated wild-type αLβ2 [13, 14]. The open I domain also can antagonize LFA-1-dependent adhesion in vitro, lymphocyte homing in vivo, and firm adhesion on high endothelial venules [15]. The locked-open HA I domain therefore can be used as a target to discover antagonists such as antibodies that are specific for the activated conformation for use in diagnosis and treatment of diseases. As only the open HA I domain binds the ligand with HA, we hypothesize that antagonists specific for the open I domain would be sufficient to block LFA-1-mediated adhesive functions. Most known integrin antagonists bind the closed and open forms. Antagonists specific for the HA αL I domain have not been described.

Using phage display, we identified and characterized a fully human antibody, AL-57, which recognizes the open HA αL I domain. This antibody preferentially binds to the active conformation of LFA-1 and blocks LFA-1-mediated adhesion and lymphocyte proliferation. These results support our hypothesis that an antagonistic antibody targeting the open HA αL I domain is sufficient to inhibit LFA-1-mediated adhesive functions.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cell culture

Stable K562 cell lines that express αLβ2 heterodimers containing locked-open or -closed I domains were established as described previously [13]. Cells were cultured in RPMI-1640 medium supplemented with 10% heat-inactivated FBS, 2 mM L-glutamine, 0.1 mM nonessential amino acids, puromycin (4 μg/ml), penicillin (100 Units/ml), and streptomycin (100 μg/ml). PBMCs were isolated from healthy donors by Ficoll-Paque (Amersham Pharmacia, Little Chalfont, UK; Cat. No. 17-1440-03) density gradient centrifugation and were cultured in RPMI-1640 medium supplemented with 10% heat-inactivated FBS, 2 mM L-glutamine, 0.1 mM nonessential amino acids, 1 mM sodium pyruvate, penicillin (100 units/ml), and streptomycin (100 μg/ml). Primary human keratinocytes (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA; Cat. No. 12332-011) were cultured in defined keratinocyte serum-free medium (Invitrogen; Cat. No. 10744-019). All cell cultures were incubated at 37°C in a humidified atmosphere with 5% CO2.

Phage display library selections

Selections were performed using a human Fab phagemid library FAB-300, essentially as described [24]. Purified locked-open HA, locked-closed LA, and wild-type I domains were prepared as described [22]. I Domains were biotinylated using the biotinylating reagent EZ-Link Sulfo-NHS-LC-Biotin (Pierce, Rockford, IL; Cat. No. 21335) following the manufacturer’s instructions. Biotinylated locked-open HA I domain was used as the target for selection, and biotinylated wild-type I domain was used for depletion. Biotinylated proteins were captured on streptavidin-coated magnetic Dynabeads M-280 (Dynal Biotech, Inc., Lake Success, NY; Cat. No. 112.06) before incubation with phage. In Round 1, ~1012 FAB-300 phage and beads were each blocked at room temperature (RT) for 1 h with PBS containing 2% (w/v) nonfat dry milk (MPBS). The blocked phage were first depleted on biotinylated wild-type I domain immobilized on beads. Depleted phage were then incubated at RT for 1 h with biotinylated HA I domain immobilized on beads. To remove unbound phage, the beads were washed five times with MPBS containing 0.1% (v/v) Tween-20, five times with PBS containing 0.1% (v/v) Tween-20, and two times with PBS. Phage still bound on beads were allowed to infect Escherichia coli cells. Phage were rescued and underwent a second round of selection identical to the first, except the target amount of HA I domain was halved. A third round was performed identically to the second, except that after washing the beads, phage were eluted with 40 mM EDTA, and eluted phage were used to infect E. coli cells.

Screening for HA I domain binders by phage ELISA

Phage enriched from the third round of selection were screened for binders specific to the HA I domain by Fab-phage ELISA as described [24]. In brief, Immulon 2HB 96-well plates (Thermo LabSystems, Beverly, MA; Cat. No. 3455) were sequentially coated with 100 ng per well streptavidin (Pierce; Cat. No. 21120) and 50 ng per well biotinylated HA I domain for target plates or wild-type I domain for background plates. After being blocked with 2% (w/v) nonfat milk in PBS, the coated plates were incubated with 1:2 rescued phage cultures diluted overnight for 1 h at RT. After being washed with PBS, 0.1% (v/v) Tween 20, the plates were incubated with HRP-conjugated anti-M13 antibody (Amersham Pharmacia; Cat. No. 27-9421-01) for 1 h, washed, developed with tetramethylbenzidine peroxidase substrate solution (Kirkegaard and Perry Laboratories, Gaithersburg, MD; Cat. No.50-76-03), and read at 450 nm wavelength on an ELISA plate reader.

Whole-cell ELISAs using unfixed HA and LA cells were also performed to screen for cell binders. Cells were harvested and resuspended at a density of 106 cells per ml in PBS, 4% (w/v) BSA, 0.05% (w/v) sodium azide, and 0.05% (v/v) Tween 20 with 10 mM MgCl2 or with 1 mM EDTA. Cells (100 μL; 105) per well were then seeded into a 96-well plate. Cells in each well were incubated with 109-purified phage in the same buffer. After washes, bound phage were detected using HRP-conjugated anti-M13 antibody as described above.

Cell-binding assay

Whole human IgG (hIgG1 or hIgG4) of AL-57 was reformatted from Fab as described previously [25]. In addition, two germline amino acid substitutions were introduced in framework regions of the IgG4 light chain. AL-57 IgG1 was tested for cell-binding activity on HA and LA cells by indirect immunofluorescence staining and flow cytometric analysis. Cell staining with the murine mAb MHM24 developed by Hildreth et al. [26] was run in parallel as a control. Using protein A beads (Amersham Biosciences; Cat. No. 17-1279-01), MHM24 was purified from hybridoma medium obtained from the Developmental Studies Hybridoma Bank developed under the auspices of the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development and maintained by the University of Iowa, Department of Biological Sciences (Iowa City). HA and LA cells were harvested and resuspended in staining buffer [PBS, 2 mM MgCl2, 1% (w/v) BSA, and 0.05% (w/v) sodium azide]. Cells were seeded into a 96-well plate at a density of 2 × 105 cells per well and incubated with AL-57 IgG1, hIgG1, control, or MHM24 at indicated concentrations for 30 min at RT with gentle rocking. After two washes with the staining buffer, cells were incubated for 20 min at 4°C with a secondary, PE-conjugated, anti-hIgG (H+L, Jackson ImmunoResearch Laboratories, West Grove, PA; Cat. No. 709-116-149) or anti-mouse IgG (H+L, Jackson ImmunoResearch Laboratories; Cat. No. 715-116-150). Stained cells were then washed, resuspended in staining buffer, and measured using a GUAVA cell analyzer (GUAVA PCA-96, GUAVA Technologies Inc., Hayward, CA).

AL-57 IgG and ICAM-1 were tested for cell binding on PBMCs. Cells were harvested, washed once with Hanks’ balanced salt (HBS) buffer (20 mM Hepes buffer in HBSS) containing 10 mM EDTA, and then twice with HBS buffer. Cells were resuspended in HBS buffer and seeded into a 96-well plate at a density of 2 × 105 cells per well. Following centrifugation, cell pellets were resuspended in 50 μl activating buffer (HBS buffer, 10 mM MgCl2, and 2 mM EGTA) or inactivating buffer (HBS buffer, 2 mM CaCl2, and 2 mM MgCl2). For certain wells, PMA (Sigma Chemical Co., St. Louis, MO; Cat. No. P-8139) or DTT was added to a final concentration of 10 ng/ml or 500 μM, respectively. For protein kinase C (PKC) inhibition studies, cells were pretreated with 10 μM GF109203 (bisindolylmaleimide, Calbiochem, San Diego, CA; Cat. No. 203290) or 1 μM staurosporine (Sigma Chemical Co.; Cat. No. S5921) for 10 min at 37°C prior to the addition of PMA. Cells in inactivating or activating buffer were incubated for 20 min at 37°C, and then AL-57 IgG4, hIgG4 control, or MHM24 was added to each well to a final concentration of 10 μg/ml and allowed to incubate with cells for 30 min at RT with gentle rocking. Cells were then washed twice with HBS buffer containing 0.05% (w/v) sodium azide, stained with the appropriate PE-labeled secondary antibody, and measured using the GUAVA cell analyzer as described above. For ICAM-1 binding to PBMCs, the procedure was the same as for AL-57 IgG4 binding, except that a soluble, multimeric, ICAM-1 complex was used for staining of cells. To prepare the multimeric complex, human ICAM-1-Fc fusion protein (R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN; Cat. No. 720-IC) was biotinylated as described above, mixed at a 4:1 molar ratio with PE-labeled streptavidin (Rockland Immunochemicals for Research, Gilbertsville, PA; Cat. No. S000-08), and incubated for at least 15 min at RT. The final concentration of ICAM-1-Fc in the complex was 10 μg/ml. Cells that were incubated with the same amount of PE-labeled streptavidin alone were used as negative controls.

ICAM-1 blocking assay

AL-57 IgG1 was tested for its ability to inhibit ligand binding to HA cells and PBMCs using an ICAM-1 blocking assay. Cells were harvested, washed once with HBS buffer containing 10 mM EDTA, and washed twice with HBS buffer. Cells were seeded into a 96-well plate at a density of 2 × 105 cells per well. Following centrifugation, cells were resuspended in HBS buffer containing 10 mM MgCl2 and 2 mM EGTA or HBS buffer with 2 mM MnCl2. Myeloma hIgG (Calbiochem; Cat. No. 400120) was added to a final concentration of 75 μg/ml to block FcRs. After a 20-min incubation at 37°C, serially diluted AL-57 IgG1 or MHM24 was added to the cells. Subsequently, a soluble, multimeric ICAM-1 complex prepared as described above, was added to a final concentration of 2 μg/ml for ICAM-1-Fc. Cells were incubated for 30 min at RT, washed, resuspended in HBS buffer, 0.05% (w/v) sodium azide, and measured using the GUAVA cell analyzer.

Keratinocyte adhesion assay

The assay was carried out essentially as described previously [27]. Subcon-fluent human keratinocytes were harvested, resuspended in assay medium (RPMI 1640 with 10% heat-inactivated FBS, penicillin at 100 units/ml, and streptomycin at 100 μg/ml), seeded into a flat-bottom 96-well plate at a cell density of 5 ×104 cells per well, and cultured overnight at 37°C. HA cells were harvested and labeled with calcein AM (20 μg/ml, Molecular Probes, Junction City, OR; Cat. No. C3100MP) for 45 min at 37°C. After three washes, HA cells were resuspended in assay medium, seeded into a new, 96-well plate at a cell density of 1 × 105 cells per well, and incubated with serially diluted IgG for 30 min at 4°C. Labeled HA cells were then transferred to the keratinocyte monolayer following removal of medium and incubated for 1 h at 37°C. After five washes with warm assay medium to remove unattached cells, remaining cells were photographed using fluorescent microscopy, and total fluorescence was measured using a fluorescence plate reader.

PHA-induced lymphocyte proliferation assay

Freshly isolated PBMCs were seeded into a 96-well plate at a density of 5 × 104 cells per well and incubated in culture medium with a Mg2+ concentration adjusted to the physiological concentration of 0.8 mM in the presence of PHA (Sigma Chemical Co.; Cat. No. L4144) at 1 μg/ml. Serially diluted AL-57 IgG1 or MHM24 was added into each well. Cells were incubated for 3 days at 37°C and analyzed for proliferation with a BrdU chemiluminescent immunoassay (Roche Applied Science, Indianapolis, IN; Cat. No. 1 669 915) following the manufacturer’s instructions.

RESULTS

Identification of a human antibody to the HA αL I domain of LFA-1

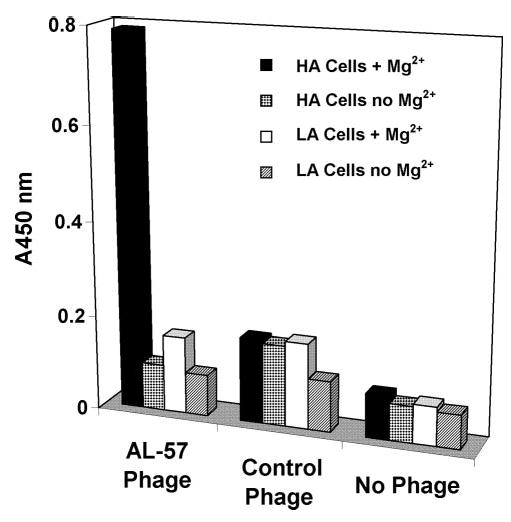

To identify an antagonistic antibody against the HA I domain, we performed phage-display library selections using the isolated locked-open HA I domain as target. The human Fab-phage library used was FAB-300 with a diversity of 1 × 1010. This library had been constructed by cloning V-genes from autoimmune patients [VLCL and VH-complementary determining region 3 (CDR3)] and synthetic VH-CDR1/2 into a phage-mid vector using oligonucleotide-assisted cleavage and ligation [24, 28]. The library was first depleted with the isolated, inactive, wild-type I domain and then underwent selection against the HA I domain. In this way, binders specific to the HA I domain protein were enriched following each round of selection. After three rounds of selection, a sample of isolates was screened using purified HA and wild-type I domains as targets in phage ELISA. A number of isolates showed significantly higher signal when HA I domain was the target than when wild-type I domain was the target (data not shown). These isolates were then tested in whole cell ELISA using unfixed HA and LA cells to determine their cell-binding specificities. One phage isolate, designated AL-57 (GenBank Accession Number DQ233247 for the heavy-chain variable region sequences and DQ233248 for the light-chain variable region sequences), bound to HA cells but not to LA cells (Fig. 1). Its binding to HA cells was dependent on Mg2+, as it did not bind to HA cells in the absence of Mg2+. On LA cells, it did not show any binding in the presence or absence of Mg2+. Thus, AL-57 was specific for HA cells.

Fig. 1.

AL-57 Fab-phage specifically binds to HA cells in a Mg2+-dependent manner. Whole cell ELISAs were carried out with unfixed HA and LA cells in the presence or absence of Mg2+. ELISA signals of AL-57 phage, a negative control phage, and no phage control are shown. Absorbance at 450 nm (A450 nm) of each sample condition is plotted in the histogram.

To characterize further the AL-57 Fab-phage isolate, the Fab was reformatted into a whole hIgG (IgG1 or IgG4) as described previously [25]. AL-57 IgG was then tested in cell-binding and functional assays.

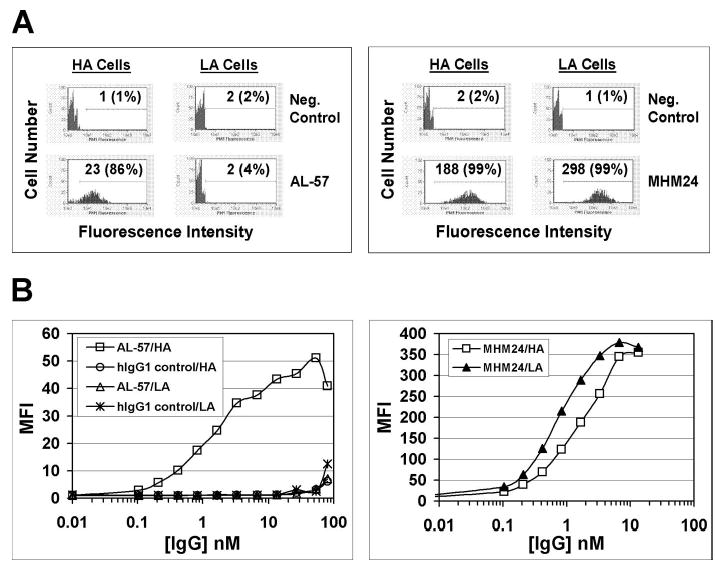

AL-57 IgG specifically binds to the activated and HA form of LFA-1

The cell-binding specificity of AL-57 IgG1 was determined using flow cytometric analysis with HA and LA cells, which were incubated with serially diluted AL-57 IgG1 or hIgG1 control followed by staining with a PE-conjugated secondary anti-hIgG. As shown in Figure 2, AL-57 IgG1 bound to HA cells in a dose-dependent manner but did not bind to LA cells. The hIgG1 control did not bind to HA or LA cells. Our results indicated that AL-57 IgG1, like its Fab-phage counterpart, bound specifically to the HA I domain of the αL subunit. For comparison, the binding activity of the murine mAb MHM24 was tested in parallel on HA and LA cells. In contrast to AL-57 IgG1, MHM24 showed nonselective binding to both cell types (Fig. 2). The difference in MFI of AL-57- and MHM24-stained cells was likely a result of the use of different PE-labeled secondary antibodies, anti-hIgG-PE for AL-57 and anti-mouse IgG-PE for MHM24.

Fig. 2.

AL-57 IgG1 specifically binds to HA cells but not LA cells. Binding of AL-57 IgG1 and MHM24 to HA and LA cells was determined by flow cytometric analysis. (A) Representative histograms of samples in the absence or presence of AL-57 IgG1 or MHM24 at 1.7 nM. The x-axis depicts the relative fluorescence intensity of individual cells, and the y-axis represents the cell number. Neg. Control indicates negative control with just the secondary PE-labeled antibody used for staining. The numbers shown are relative values of mean fluorescence intensity (MFI) with relative percentages of positive cells in parenthesis. (B) Concentration-dependent binding of AL-57 IgG1, hIgG1 control, and MHM24 to HA and LA cells. Cells were incubated with serially diluted AL-57 IgG1, hIgG1 control, or MHM24, followed by staining with secondary anti-hIgG- or anti-mouse IgG-PE. Plotted in each diagram is MFI as a function of the IgG concentration.

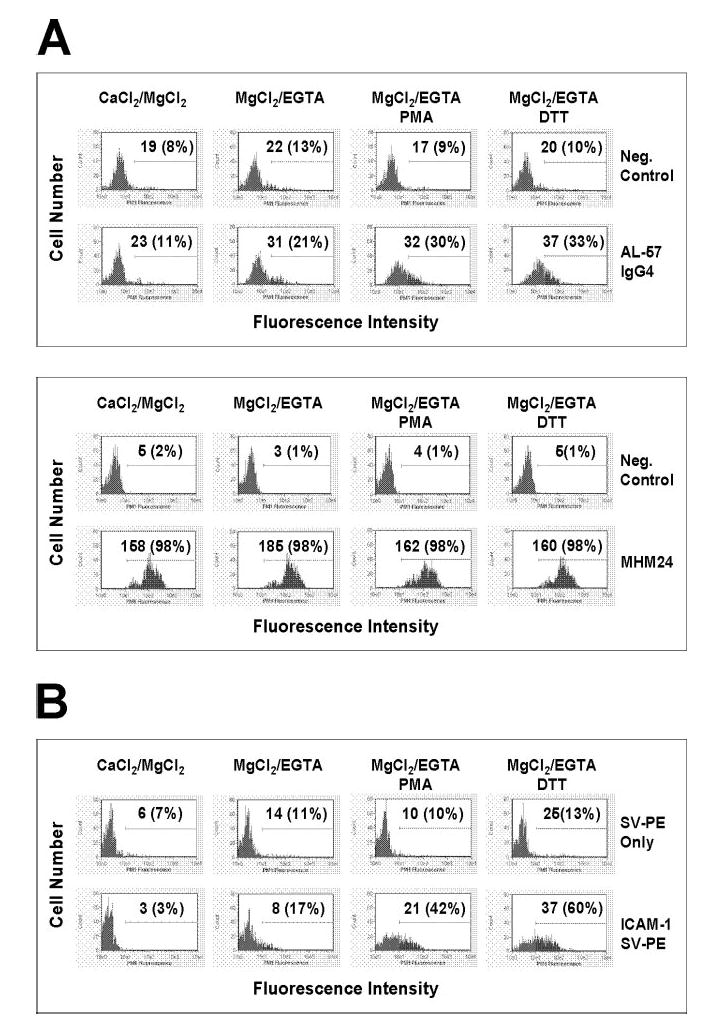

Having shown that AL-57 IgG was specific for HA cells expressing αLβ2 with a locked-open HA I domain, we tested whether AL-57 IgG also bound to the HA form of wild-type αLβ2 expressed on PBMCs. To minimize background caused by FcR binding, AL-57 IgG4 was used in the binding assay. Before staining with the antibody, PBMCs were incubated with inactivating buffer containing 2 mM CaCl2 and 2 mM MgCl2 or activating buffer containing 10 mM MgCl2 and 2 mM EGTA. It is known that Ca2+ at high concentrations inhibits the HA I domain [23, 29, 30], whereas Mg2+ and EGTA induce a HA form of LFA-1 [29, 31, 32]. Consistent with its specificity for the HA I domain, AL-57 IgG4 showed no binding to PBMCs in inactivating buffer but showed some binding in activating buffer (Fig. 3A). We next tested AL-57 IgG4 binding on PBMCs after treatment with PMA, which has been shown to induce a HA form of LFA-1 [18, 33]. As shown in Figure 3A, PMA treatment significantly enhanced AL-57 IgG4 binding in activating buffer, further supporting our findings that AL-57 IgG4 preferentially bound to the HA form of LFA-1. PMA induced AL-57 binding in inactivating and activating buffer; however, PMA in activating buffer induced more AL-57 binding than in inactivating buffer, likely as a result of the additive effect of PMA and MgCl2/EGTA (data not shown). A hIgG4 control antibody did not show any binding to PBMCs under any conditions tested (data not shown).

Fig. 3.

AL-57 IgG4 and ICAM-1 bind to the activated HA form of LFA-1 on PBMCs. Binding of AL-57 IgG4 (A) and ICAM-1 (B) to PBMCs with inactivating buffer (CaCl2/MgCl2) or with activating buffer (MgCl2/EGTA) in the presence or absence of PMA (10 ng/ml) or DTT (500 μM) was determined by flow cytometric analysis as described in Materials and Methods. The concentration of each IgG or ICAM-1 used was 10 μg/ml. For AL-57 staining, Neg. Control indicates negative control with just the secondary PE-labeled antibody used for staining; MHM24 was used as a control that did not distinguish between the HA and LA forms of LFA-1. For ICAM-1 staining, a multimeric complex [ICAM-1/streptavidin (SV)-PE] of biotinylated human ICAM-1-Fc and PE-labeled streptavidin was used; SV-PE only indicates negative control with just the PE-labeled streptavidin used for staining. Shown here are representative histograms of samples under indicated conditions. The x-axis depicts the fluorescence intensity of individual cells, and the y-axis represents the cell number. The numbers shown are relative values of MFI with relative percentages of positive cells in parenthesis.

Cell-binding results from memory T lymphocytes demonstrated that upon activation by PMA or a chemokine, stromal cell-derived factor-1, the number of activation-dependent epitopes determined by AL-57 Fab was increased greatly, approximately tenfold, similar to the number of activation-dependent epitopes determined by another activation-sensitive mAb, KIM127, which maps to the leg of the β2 subunit (M. Shimaoka et al., manuscript in preparation). AL-57 and KIM127 activation-dependent neoepitopes were expressed on a subpopulation of ~10% of LFA-1 molecules on the surface of agonist-stimulated cells. These results further support that AL-57 is able to detect affinity up-regulation of LFA-1.

As a selective binder to the HA form of LFA-1, AL-57 IgG could serve as a reporter for the HA conformation of LFA-1. We thus tested AL-57 IgG4 binding to PBMCs following treatment with DTT. This reducing agent has been shown to modulate the adhesive state of several different integrins including LFA-1 [34–37]. It is proposed that DTT stimulates LFA-1/ICAM-1 adhesive interactions by promoting conformational changes in LFA-1 or patterns of organization on the cell membrane [37]. Our results demonstrated that as with PMA, DTT significantly enhanced AL-57 IgG4 binding in activating buffer (Fig. 3A), indicating that DTT also induced the HA form of LFA-1.

Unlike AL-57 IgG4, which bound only to activated LFA-1 on PBMCs, MHM24 bound to nearly l00% of the cells in inactivating or activating buffer, and its binding was not affected by PMA or DTT treatment (Fig. 3A). These results with PBMCs were consistent with those from HA and LA cells, confirming that MHM24 was a nonselective binder to LFA-1.

Ligand binding to LFA-1 depends on the affinity state of LFA-1. The affinity of the αL I domain for ligand can be 200 nM for the locked-open or activated wild-type I domain and 2 mM for the locked-closed or inactive wild-type I domain [1]. As AL-57 bound to the HA I domain only, we hypothesized that AL-57 and the primary ligand ICAM-1 would exhibit a similar binding profile on PBMCs. To increase sensitivity for detection of ligand binding, we used a multimeric ICAM-1 complex formed by mixing biotinylated human ICAM-1-Fc fusion protein and PE-labeled streptavidin at a 4:1 ratio. As shown in Figure 3B, multimeric ICAM-1 exhibited some binding to PBMCs in activating buffer but not in inactivating buffer, and its binding was enhanced significantly by PMA or DTT treatment. These results indicated that AL-57 IgG might behave similarly to ICAM-1 in binding to LFA-1.

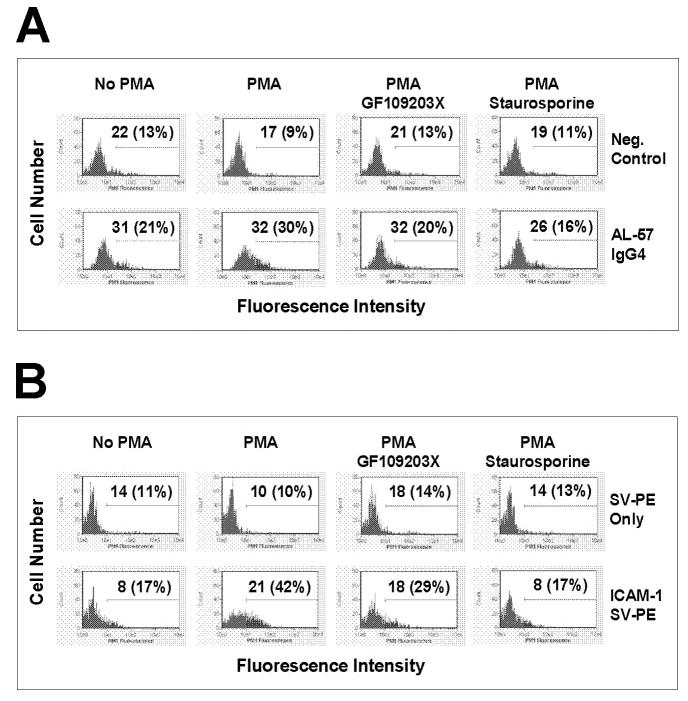

PMA-enhanced LFA-1 adhesiveness is mediated through activation with PKC [17]. To determine if PMA-induced binding of AL-57 or ICAM-1 was mediated by PKC, PBMCs were incubated with activating buffer in the presence of known PKC inhibitor GF109203X at 10 μM or staurosporine at 1 μM prior to PMA treatment. As shown in Figure 4, PMA-induced AL-57 IgG4 or multimeric ICAM-1 binding on PBMCs was blocked by either of these inhibitors. The binding signal on PKC inhibitor-treated cells was comparable with the level on cells without any PMA treatment. These results indicated that PMA-induced binding of AL-57 or ICAM-1 on PBMCs was mediated by an inside-out signaling pathway involving PKC.

Fig. 4.

PMA-induced enhancement in AL-57 and ICAM-1 binding to PBMCs is blocked by PKC inhibitors. Binding of AL-57 IgG4 (A) and ICAM-1 (B) to PBMCs with activating buffer (MgCl2/EGTA) in the presence or absence of PMA (10 ng/ml) and PKC inhibitor GF109203X (10 μM) or staurosporine (1 μM) was determined by flow cytometric analysis. The concentration of AL-57 IgG4 or ICAM-1 used was 10 μg/ml. For AL-57 IgG4 staining, Neg. Control indicates negative control with just the secondary PE-labeled antibody used for staining; MHM24, a nonselective binder, was also used as a control. For ICAM-1 staining, a multimeric complex (ICAM-1/SV-PE) was used; SV-PE only indicates negative control with just the PE-labeled streptavidin used for staining. Shown here are representative histograms of samples under indicated conditions. The x-axis depicts the fluorescence intensity of individual cells, and the y-axis represents the cell number. The numbers shown are relative values of MFI with relative percentages of positive cells in parenthesis.

Taken together, our results with HA and LA cells as well as PBMCs demonstrated that AL-57 binds not only to the locked-open HA I domain but also to the HA state of wild-type LFA-1 and can be used as a reporter for the HA conformation of LFA-1.

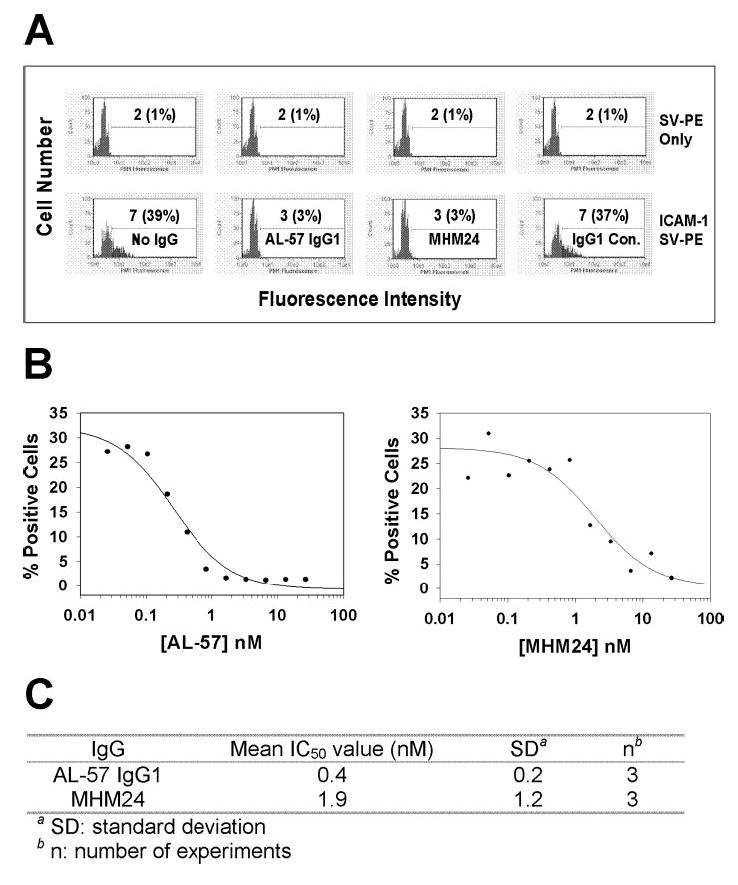

AL-57 IgG blocks ICAM-1 binding to LFA-1

AL-57 and the ligand ICAM-1 showed specific binding to the HA form of LFA-1. Thus, it was possible that AL-57 would compete with ligand binding to the HA I domain. To test this, we performed ICAM-1 blocking assays with AL-57 IgG1. Ligand binding in the presence or absence of AL-57 IgG1 was measured using a soluble multimeric ICAM-1 complex. As shown in Figure 5A, AL-57 at 4 μg/ml (26.8 nM) completely blocked multimeric ICAM-1 binding to HA cells, as did the positive control antibody MHM24, whereas the hIgG1 control did not demonstrate any inhibition of ICAM-1 binding. The IC50 values of AL-57 and MHM24 for blocking ICAM-1 binding on HA cells were determined by staining cells (2×105 per sample) with ICAM-1-Fc (2 μg/ml) in multimeric complex with PE-labeled streptavidin in the presence of serially diluted IgGs. On HA cells, AL-57 demonstrated an IC50 value of 0.4 ± 0.2 nM, lower than that of MHM24 (1.9±1.2 nM), based on three independent experiments (Fig. 5, B and C). On human PBMCs, AL-57 also inhibited multimeric ICAM-1 binding with an IC50 value of 0.6 ± 0.4 nM, comparable with that of MHM24 (0.3±0.2 nM), based on four independent experiments (Table 1).

Fig. 5.

AL-57 IgG1 inhibits ICAM-1 binding to HA cells. ICAM-1 binding in the presence or absence of each IgG was measured by staining HA cells with a soluble, multimeric ICAM-1 complex with ICAM-1-Fc concentration at 2 μg/ml and flow cytometric analysis. (A) Representative histograms of samples in the absence or presence of AL-57 IgG1, MHM24, or hIgG1 control at 4 μg/ml (26.8 nM). The x-axis depicts the fluorescence intensity of individual cells, and the y-axis represents the cell number. SV-PE only indicates negative control with PE-labeled streptavidin alone for staining. The numbers shown are relative values of MFI with relative percentages of positive cells in parenthesis. (B) IC50 determination of AL-57 IgG1 and MHM24. The percentage of positive cells from each sample was plotted as a function of the IgG concentration. From the representative plots shown here, IC50 values were calculated to be 0.3 nM for AL-57 IgG1 and 2 nM for MHM24 using SigmaPlot 8.0 software. (C) Summary of IC50 values from three independent experiments.

TABLE 1.

AL-57 IgG1 Blocks ICAM-1 Binding to Human PBMCs

SD, Standard deviation;

n, number of experiments.

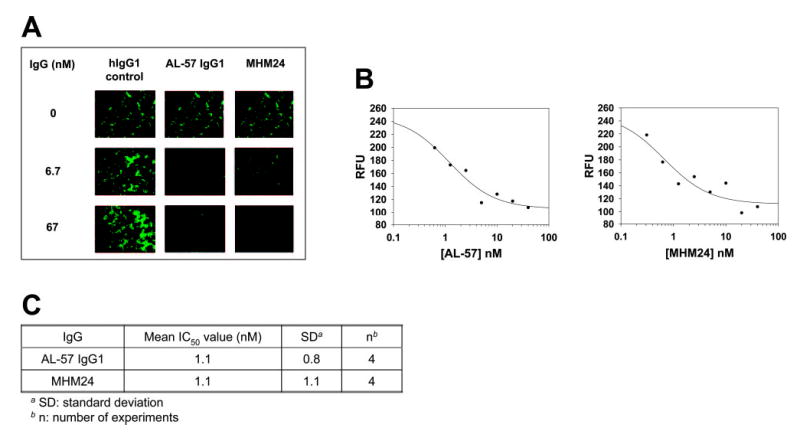

AL-57 IgG blocks HA cell adhesion to keratinocytes

As an adhesion molecule, LFA-1 mediates leukocyte adhesion during cellular interactions critical for immune and inflammatory responses. Anti-CD11a antibodies such as MHM24 have been shown to inhibit LFA-1-mediated T cell function [27, 38, 39]. To test if AL-57 is able to inhibit LFA-1 function, we performed keratinocyte adhesion assays. Calcein AM-labeled HA cells were preincubated with AL-57 IgG1, hIgG1 control, or MHM24 and added to a monolayer of human keratinocytes. As shown in Figure 6A, like MHM24, AL-57 IgG1 at 6.7 nM completely blocked HA cell adhesion to human keratinocytes, whereas the hIgG1 control did not block adhesion. AL-57 IgG1 exhibited an IC50 value of 1.1 ± 0.8 nM similar to that of MHM24 (1.1±1.1 nM), based on four independent experiments (Fig. 6, B and C).

Fig. 6.

AL-57 IgG1 inhibits HA cell adhesion to keratinocytes. HA cells were labeled with calcein AM, preincubated with AL-57 IgG1, MHM24, or hIgG1 control, and added to a keratinocyte monolayer. After washing to remove unattached cells, remaining cells were photographed using fluorescence microscopy, and total fluorescence was measured using a fluorescence plate reader. (A) Representative pictures from samples treated without or with AL-57 IgG1, MHM24, or hIgG1 control at concentrations of 6.7 or 67 nM. (B) IC50 determination of AL-57 IgG1 and MHM24. Relative fluorescence units (RFU) from each sample were plotted as a function of the IgG concentration. From the representative plots shown here, IC50 values were calculated to be 1.2 nM for AL-57 IgG1 and 0.7 nM for MHM24 using SigmaPlot 8.0 software. (C) Summary of IC50 values from four independent experiments.

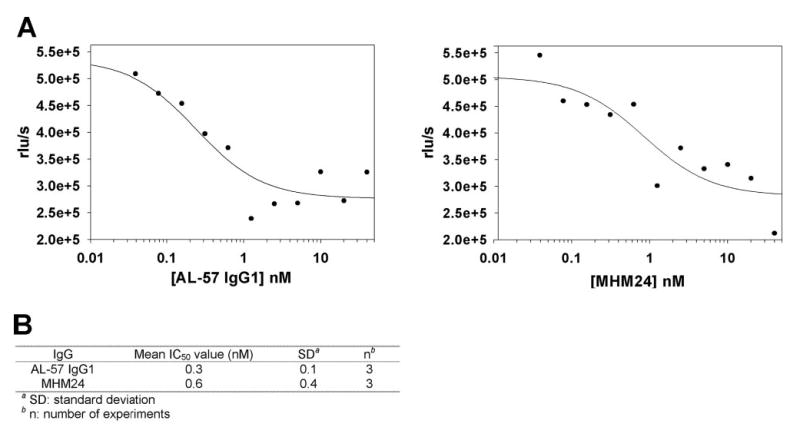

AL-57 IgG blocks PHA-induced lymphocyte proliferation

To determine the effect of AL-57 on the function of wild-type LFA-1, we tested the effect of AL-57 IgG1 on PHA-induced lymphocyte proliferation in which LFA-1 plays an important role by not only mediating T cell adhesion but also regulating signal transduction [40–42]. In this assay, PBMCs were treated with PHA (1 μg/ml) in the presence of Mg2+ at a physiological concentration of 0.8 mM. Results from three different donor lots of PBMCs demonstrated that AL-57 IgG1 blocked PHA-induced lymphocyte proliferation with an IC50 value of 0.3 ± 0.1 nM, comparable with that of MHM24 (0.6±0.4 nM; Fig. 7).

Fig. 7.

AL-57 IgG1 inhibits PHA-induced cell proliferation. PBMCs were treated with PHA at 1 μg/ml in the presence of Mg2+, serially diluted IgG for 3 days, and then analyzed for proliferation using a BrdU chemiluminescence assay. (A) IC50 determination of AL-57 IgG1 and MHM24. Relative luminescence units per second (rlu/s) from each sample were plotted as a function of the IgG concentration. From the representative plots shown here, IC50 values were calculated to be 0.2 nM for AL-57 IgG1 and 0.8 nM for MHM24, using SigmaPlot 8.0 software. (B) Summary of IC50 values from three independent experiments.

DISCUSSION

In this study, we identified and characterized a human antibody, which preferentially binds to the activated HA form of LFA-1 by screening a Fab-displaying phagemid library using a locked-open HA I domain of the αL subunit as target. The library selection was performed by first depleting the library on the isolated, inactive wild-type I domain and then panning against the locked-open HA I domain. A specific isolate, AL-57, was identified by Fab-phage ELISA. AL-57 bound to HA cells but not LA cells, and the binding was dependent on the divalent cation, as no binding was observed in the absence of Mg2+. The locked-open HA I domain contains only one cation molecule at the MIDAS. Hence, the AL-57 binding site likely involves the metal ion at the MIDAS. In contrast to AL-57, the murine mAb MHM24 did not distinguish between the HA and LA I domains, as it bound to HA and LA cells. Thus, AL-57 is selective for the locked-open HA I domain. AL-57 also recognized an engineered, disulfide-locked intermediate affinity (IA) L161C/F299C αL mutant I domain [22] but with much LA (Kd of 1.5–7.9 μM), ~200-fold lower than that of the HA I domain (Kd of 7–39 nM; M. Shimaoka et al., manuscript in preparation). Like AL-57, ICAM-1 binds the IA I domain with IA (Kd of 3–9 μM), lower than that of the HA I domain (Kd of 150–360 nM) [22]. Thus, AL-57 and ICAM-1 share the same characteristics in binding to LFA-1, namely, the progressive increases in affinity to IA and HA I domains, little binding to the LA I domain, and the Mg2+ dependence for binding, indicating that AL-57 is a ligand mimetic.

Consistent with its selectivity to the locked-open HA I domain, AL-57 IgG4 bound to wild-type LFA-1 on PBMCs in the presence of Mg2+ and EGTA, known to induce a HA form of LFA-1 but not in the presence of mM concentrations of Ca2+, known to maintain LFA-1 in a LA state. It is remarkable that AL-57 IgG4 binding in the presence of Mg2+ and EGTA was enhanced significantly by a transient treatment with PMA. The binding profile of the ligand ICAM-1 on PBMCs was the same as that of AL-57 IgG4. These results verified further that AL-57 IgG, like the ligand ICAM-1, bound to the activated HA form of LFA-1. The PMA-induced, dramatic increase in AL-57 IgG4 and ICAM-1 binding indicated that phorbol ester stimulation induced HA LFA-1, rather than just receptor clustering, as suggested by previous reports [29, 43, 44]. Our data with PMA were consistent with the detection of increased affinity for ligand after PMA stimulation, as measured by a sensitive ligand displacement assay using radiolabeled Fab fragments against the αL subunit [18]. These results also support recent findings derived from quantitative analysis of LFA-1 distribution with fluorescence resonance energy transfer and high resolution fluorescence microscopy that PMA activates adhesiveness, predominantly through affinity rather than valency regulation [33]. It is observed that activators that promote adhesion through LFA-1 cannot change LFA-1 clustering in the absence of ligand [33]. Monomeric binding of ICAM-1 induces profound, conformational changes in LFA-1 but not alterations in clustering, whereas multivalent binding of ICAM-1 induces substantial microclustering [33]. PMA has been shown to increase the LFA-1 diffusion on the cell surface, which results from the release of cytoskeletal constraints on LFA-1 [45]. The released LFA-1 does not facilitate ligand-independent clustering but rather, ligand-dependent accumulation of LFA-1 at the substrate contact interface, resulting in adhesion strengthening [33].

As a specific antibody targeting the HA form of LFA-1, AL-57 could serve as a reporter for the HA conformation of LFA-1. For example, we tested AL-57 IgG4 binding to PBMCs following treatment with DTT, known to modulate the adhesive state of LFA-1 [37]. How DTT stimulates LFA-1/ICAM-1 adhesive interactions is not clear. It is proposed that DTT promotes conformational changes in LFA-1 or patterns of organization on the cell membrane [37]. By using AL-57 IgG as a reporter, we clearly demonstrated that like PMA, DTT also induced a HA form of LFA-1.

AL-57 and ICAM-1 bound preferentially to the active HA conformation of the I domain and required Mg2+ for binding. The structure of the I domain bound to ICAM-1 reveals an open ligand conformation in which Mg2+ in the I domain directly coordinates with Glu-241 of ICAM-1 [22]. As a result of the common features shared by AL-57 and ICAM-1, it is possible that AL-57 would bind to the MIDAS of the I domain and that an acidic residue existing in a CDR loop of AL-57 could coordinate directly with Mg2+ in the MIDAS in a similar manner as Glu-241 of ICAM-1. Indeed, sequence analysis revealed two Asp residues in CDR3 of AL-57; one of the Asp residues was retained in most of the isolates identified from an affinity-matured heavy chain CDR3 phage library, which was made using the AL-57 background (data not shown). Future structural analysis of the I domain bound with AL-57 should reveal useful information for understanding the mechanisms by which AL-57 selectively binds to the active conformation of LFA-1.

AL-57 is the first specific antagonist known to target the active conformation of the αL I domain of LFA-1. Its specificity toward the HA I domain makes AL-57 a useful research tool for detecting the HA form of LFA-1, investigating the conformational transition of LFA-1 on cells during cell migration and spreading, and studying the effects of specific inhibition of the active form of LFA-1 in vitro and in vivo.

In addition to serving as a research tool for in vitro and in vivo studies, the AL-57 antibody represents a therapeutic candidate for treatment of inflammatory and autoimmune diseases. AL-57 IgG functionally inhibited ligand ICAM-1 binding to HA cells and PBMCs, adhesion of HA cells to keratinocytes, and PHA-induced lymphocyte proliferation with in vitro potencies, at least as great as MHM24, which bound nonselectively to inactive and active forms of LFA-1. As LFA-1 plays a crucial role in many immune functions, nonselective inhibition of active and inactive LFA-1 may lead to a compromise of its physiological roles, such as host defense and thus, to unwanted immune suppression. Conversely, selective inhibition of active LFA-1 by HA conformation-specific antibody AL-57 may have more favorable pharmacokinetics, require lower and/or less frequent dosing for treatment, and result in fewer potential side-effects.

Besides the identification and characterization of a fully human antibody with therapeutic potential, our study validates the use of an engineered locked-open I domain for discovering antibodies, which not only specifically recognize the physiologically activated HA integrin receptor on the cell surface but also block ligand binding and integrin receptor-mediated, biological functions. It is challenging to use a peptide or protein domain to screen for antibodies that can recognize a physiological counterpart. Our phage display-based method clearly succeeded in identifying a conformation-specific, anti-LFA-1 antibody. This method can be applied to other integrins for identifying such specialized antibodies.

Acknowledgments

This project was supported by National Institutes of Health Grants AI063421 (M. S.) and CA31798 (T. A. S.) and the American Society of Hematology (M. S.). We thank Gary Bassill for DNA sequencing, Kristin Rookey and Judy Jacques for IgG reformatting, Shannon Hogan, Andrea Gorman, and Farrah Chaudhary for IgG expression, Csaba Pazmany for IgG purification, and Guannan Kuang and Dan Sexton for protein biotinylation. We are indebted to other Dyax colleagues for their continuous support and discussions throughout the course of this study. We also thank Rachel Kent for critical reading and helpful revision of the manuscript.

References

- 1.Shimaoka M, Takagi J, Springer TA. Conformational regulation of integrin structure and function. Annu Rev Biophys Biomol Struct. 2002;31:485–516. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biophys.31.101101.140922. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Springer TA. Adhesion receptors of the immune system. Nature. 1990;346:425–434. doi: 10.1038/346425a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.de Fougerolles AR, Springer TA. Intercellular adhesion molecule 3, a third adhesion counter-receptor for lymphocyte function-associated molecule 1 on resting lymphocytes. J Exp Med. 1992;175:185–190. doi: 10.1084/jem.175.1.185. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Carman CV, Jun C, Salas A, Springer TA. Endothelial cells proactively form microvilli-like membrane projections upon intercellular adhesion molecule 1 engagement of leukocyte LFA-1. J Immunol. 2003;171:6135–6144. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.171.11.6135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Larson RS, Springer TA. Structure and function of leukocyte integrins. Immunol Rev. 1990;114:181–217. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-065x.1990.tb00565.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Simon SI, Green CE. Molecular mechanics and dynamics of leukocyte recruitment during inflammation. Annu Rev Biomed Eng. 2005;7:151–185. doi: 10.1146/annurev.bioeng.7.060804.100423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Krueger JG. The immunologic basis for the treatment of psoriasis with new biologic agents. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2002;46:1–23. doi: 10.1067/mjd.2002.120568. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Watts GM, Beurskens FJ, Martin-Padura I, Ballantyne CM, Klickstein LB, Brenner MB, Lee DM. Manifestations of inflammatory arthritis are critically dependent on LFA-1. J Immunol. 2005;174:3668–3675. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.174.6.3668. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cather JC, Menter A. Efalizumab: continuous therapy for chronic psoriasis. Expert Opin Biol Ther. 2005;5:393–403. doi: 10.1517/14712598.5.3.393. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Oxvig C, Lu C, Springer TA. Conformational changes in tertiary structure near the ligand binding site of an integrin I domain. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1999;96:2215–2220. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.5.2215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Shimaoka M, Shifman JM, Jing H, Takagi J, Mayo SL, Springer TA. Computational design of an integrin I domain stabilized in the open high affinity conformation. Nat Struct Biol. 2000;7:674–678. doi: 10.1038/77978. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Huth JR, Olejniczak ET, Mendoza R, Liang H, Harris EA, Lupher ML, Jr, Wilson AE, Fesik SW, Staunton DE. NMR and mutagenesis evidence for an I domain allosteric site that regulates lymphocyte function-associated antigen 1 ligand binding. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2000;97:5231–5236. doi: 10.1073/pnas.97.10.5231. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lu C, Shimaoka M, Ferzly M, Oxvig C, Takagi J, Springer TA. An isolated, surface-expressed I domain of the integrin αLβ2 is sufficient for strong adhesive function when locked in the open conformation with a disulfide bond. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2001;98:2387–2392. doi: 10.1073/pnas.041606398. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lu C, Shimaoka M, Zang Q, Takagi J, Springer TA. Locking in alternate conformations of the integrin αLβ2 I domain with disulfide bonds reveals functional relationships among integrin domains. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2001;98:2393–2398. doi: 10.1073/pnas.041618598. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Shimaoka M, Lu C, Palframan R, von Andrian UH, McCormack A, Takagi J, Springer TA. Reversibly locking a protein fold in an active conformation with a disulfide bond: integrin αL I domains with high affinity and antagonist activity in vivo. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2001;98:6009–6014. doi: 10.1073/pnas.101130498. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Diamond MS, Springer TA. The dynamic regulation of integrin adhesiveness. Curr Biol. 1994;4:506–517. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(00)00111-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Dustin ML, Springer TA. T-cell receptor cross-linking transiently stimulates adhesiveness through LFA-1. Nature. 1989;341:619–624. doi: 10.1038/341619a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lollo BA, Chan KWH, Hanson EM, Moy VT, Brian AA. Direct evidence for two affinity states for lymphocyte function-associated antigen 1 on activated T cells. J Biol Chem. 1993;268:21693–21700. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Beglova N, Blacklow SC, Takagi J, Springer TA. Cysteine-rich module structure reveals a fulcrum for integrin rearrangement upon activation. Nat Struct Biol. 2002;9:282–287. doi: 10.1038/nsb779. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lee JO, Bankston LA, Arnaout MA, Liddington RC. Two conformations of the integrin A-domain (I-domain): a pathway for activation? Structure. 1995;3:1333–1340. doi: 10.1016/s0969-2126(01)00271-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Emsley J, Knight CG, Farndale RW, Barnes MJ, Liddington RC. Structural basis of collagen recognition by integrin α2β1. Cell. 2000;101:47–56. doi: 10.1016/S0092-8674(00)80622-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Shimaoka M, Xiao T, Liu JH, Yang Y, Dong Y, Jun CD, McCormack A, Zhang R, Joachimiak A, Takagi J, Wang JH, Springer TA. Structures of the α L I domain and its complex with ICAM-1 reveal a shape-shifting pathway for integrin regulation. Cell. 2003;112:99–111. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(02)01257-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Labadia ME, Jeanfavre DD, Caviness GO, Morelock MM. Molecular regulation of the interaction between leukocyte function-associated antigen-1 and soluble ICAM-1 by divalent metal cations. J Immunol. 1998;161:836–842. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hoet RM, Cohen EH, Kent RB, Rookey K, Schoonbroodt S, Hogan S, Rem L, Frans N, Daukandt M, Pieters H, et al. Generation of high-affinity human antibodies by combining donor-derived and synthetic complementarity-determining-region diversity. Nat Biotechnol. 2005;23:344–348. doi: 10.1038/nbt1067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Jostock T, Vanhove M, Brepoels E, van Gool R, Daukandt M, Wehnert A, van Hegelsom R, Dransfield D, Sexton D, Devlin M, Ley A, Mullberg J. Rapid generation of functional human IgG antibodies derived from Fab-on-phage display libraries. J Immunol Methods. 2004;289:65–80. doi: 10.1016/j.jim.2004.03.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hildreth JEK, Gotch FM, Hildreth PDK, McMichael AJ. A human lymphocyte-associated antigen involved in cell-mediated lympholysis. Eur J Immunol. 1983;13:202–208. doi: 10.1002/eji.1830130305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Werther WA, Gonzalez TN, O’Connor SJ, McCabe S, Chan B, Hotaling T, Champe M, Fox JA, Jardieu PM, Berman PW, Presta LG. Humanization of an anti-lymphocyte function-associated antigen (LFA)-1 monoclonal antibody and reengineering of the humanized antibody for binding to rhesus LFA-1. J Immunol. 1996;157:4986–4995. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Schoonbroodt S, Frans N, DeSouza M, Eren R, Priel S, Brosh N, Ben-Porath J, Zauberman A, Ilan E, Dagan S, Cohen EH, Hoogenboom HR, Ladner RC, Hoet RM. Oligonucleotide-assisted cleavage and ligation: a novel directional DNA cloning technology to capture cDNAs. Application in the construction of a human immune antibody phage-display library. Nucleic Acids Res. 2005;33:e81. doi: 10.1093/nar/gni080. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Dransfield I, Cabanas C, Craig A, Hogg N. Divalent cation regulation of the function of the leukocyte integrin LFA-1. J Cell Biol. 1992;116:219–226. doi: 10.1083/jcb.116.1.219. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Takagi J, Petre BM, Walz T, Springer TA. Global conformational rearrangements in integrin extracellular domains in outside-in and inside-out signaling. Cell. 2002;110:599–611. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(02)00935-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Dransfield I, Hogg N. Regulated expression of Mg2+ binding epitope on leukocyte integrin α subunits. EMBO J. 1989;8:3759–3765. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1989.tb08552.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Stewart M, Hogg N. Regulation of leukocyte integrin function: affinity vs. avidity J Cell Biochem. 1996;61:554–561. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-4644(19960616)61:4<554::aid-jcb8>3.0.co;2-n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kim M, Carman CV, Yang W, Salas A, Springer TA. The primacy of affinity over clustering in regulation of adhesiveness of the integrin {α}L{β}2. J Cell Biol. 2004;167:1241–1253. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200404160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Zucker MB, Masiello NC. Platelet aggregation caused by dithiothreitol. Thromb Haemost. 1984;51:119–124. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Schwartz BR, Harlan JM. Sulfhydryl reducing agents promote neutrophil adherence without increasing surface expression of CD11b/CD18 (Mac-1, Mo1) Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1989;165:51–57. doi: 10.1016/0006-291x(89)91032-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Davis GE, Camarillo CW. Regulation of integrin-mediated myeloid cell adhesion to fibronectin: influence of disulfide-reducing agents, divalent cations and phorbol ester. J Immunol. 1993;151:7138–7150. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Edwards BS, Curry MS, Southon EA, Chong AS, Graf LH., Jr Evidence for a dithiol-activated signaling pathway in natural killer cell avidity regulation of leukocyte function antigen-1: structural requirements and relationship to phorbol ester- and CD16-triggered pathways. Blood. 1995;86:2288–2301. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hildreth JEK, August JT. The human lymphocyte function-associated (HLFA) antigen and a related macrophage differentiation antigen (HMac-1): functional effects of subunit-specific monoclonal antibodies. J Immunol. 1985;134:3272–3280. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Dougherty GJ, Hogg N. The role of monocyte lymphocyte function-associated antigen 1 (LFA-1) in accessory cell function. Eur J Immunol. 1987;17:943–947. doi: 10.1002/eji.1830170708. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Schwartz D, Wong RC, Chatila T, Arnaout A, Miller R, Geha R. Proliferation of highly purified T cells in response to signaling via surface receptors requires cell-cell contact. J Clin Immunol. 1989;9:151–158. doi: 10.1007/BF00916943. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Vermot Desroches C, Rigal D, Andreoni C. Regulation and functional involvement of distinct determinants of leucocyte function-associated antigen 1 (LFA-1) in T-cell activation in vitro. Scand J Immunol. 1991;33:277–286. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3083.1991.tb01773.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Tabassam FH, Umehara H, Huang JY, Gouda S, Kono T, Okazaki T, van Seventer JM, Domae N. β2-integrin, LFA-1, and TCR/CD3 synergistically induce tyrosine phosphorylation of focal adhesion kinase (pp125(FAK)) in PHA-activated T cells. Cell Immunol. 1999;193:179–184. doi: 10.1006/cimm.1999.1472. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Stewart MP, Cabanas C, Hogg N. T cell adhesion to intercellular adhesion molecule-1 (ICAM-1) is controlled by cell spreading and the activation of integrin LFA-1. J Immunol. 1996;156:1810–1817. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Stewart MP, McDowall A, Hogg N. LFA-1-mediated adhesion is regulated by cytoskeletal restraint and by a Ca2+-dependent protease, calpain. J Cell Biol. 1998;140:699–707. doi: 10.1083/jcb.140.3.699. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kucik DF, Dustin ML, Miller JM, Brown EJ. Adhesion-activating phorbol ester increases the mobility of leukocyte integrin LFA-1 in cultured lymphocytes. J Clin Invest. 1996;97:2139–2144. doi: 10.1172/JCI118651. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]