Abstract

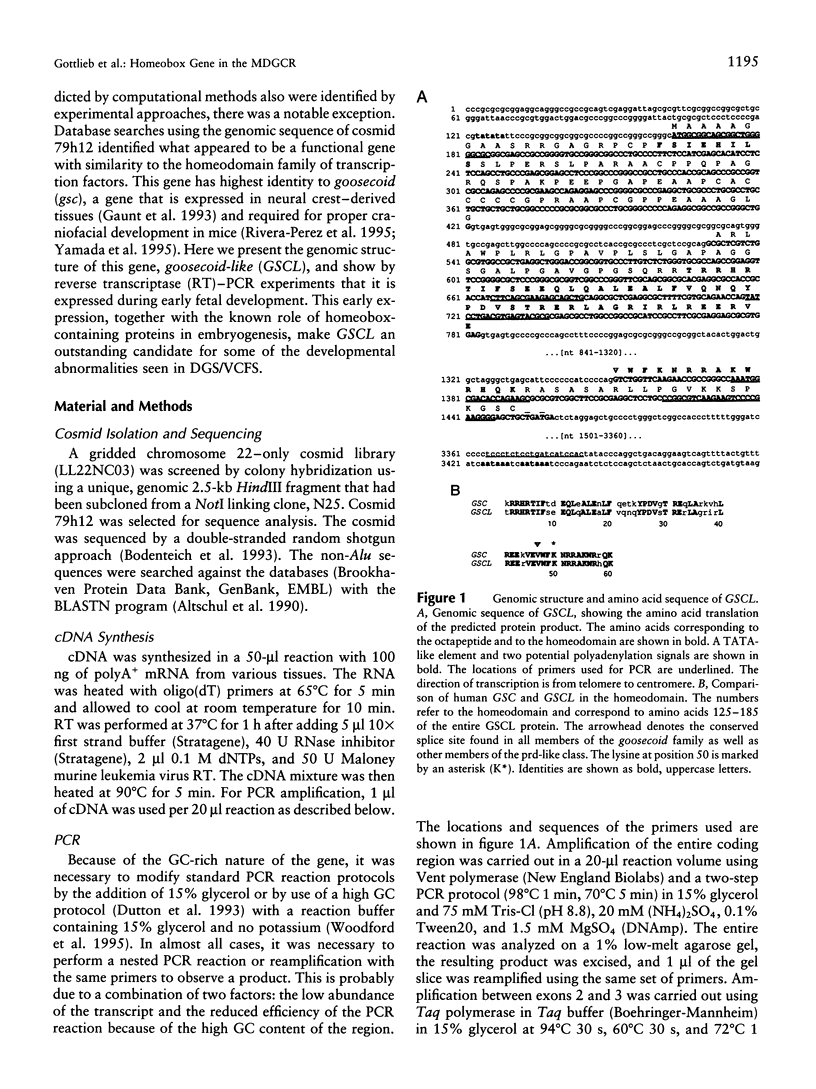

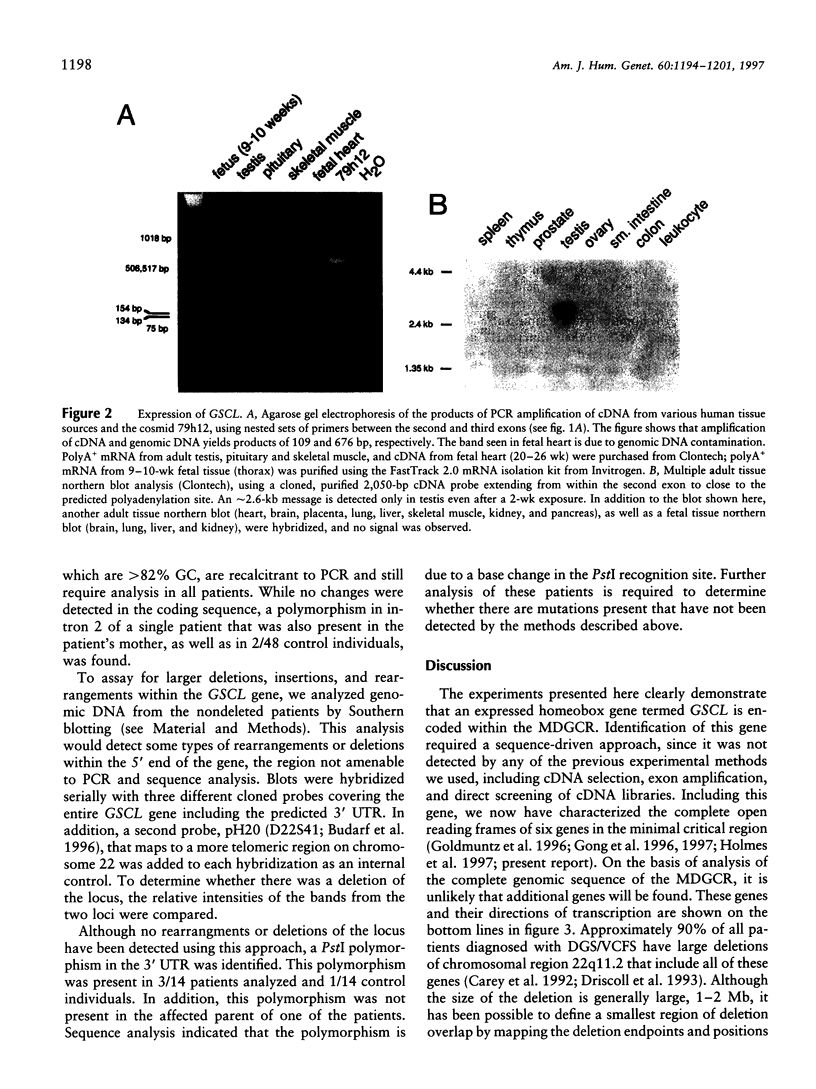

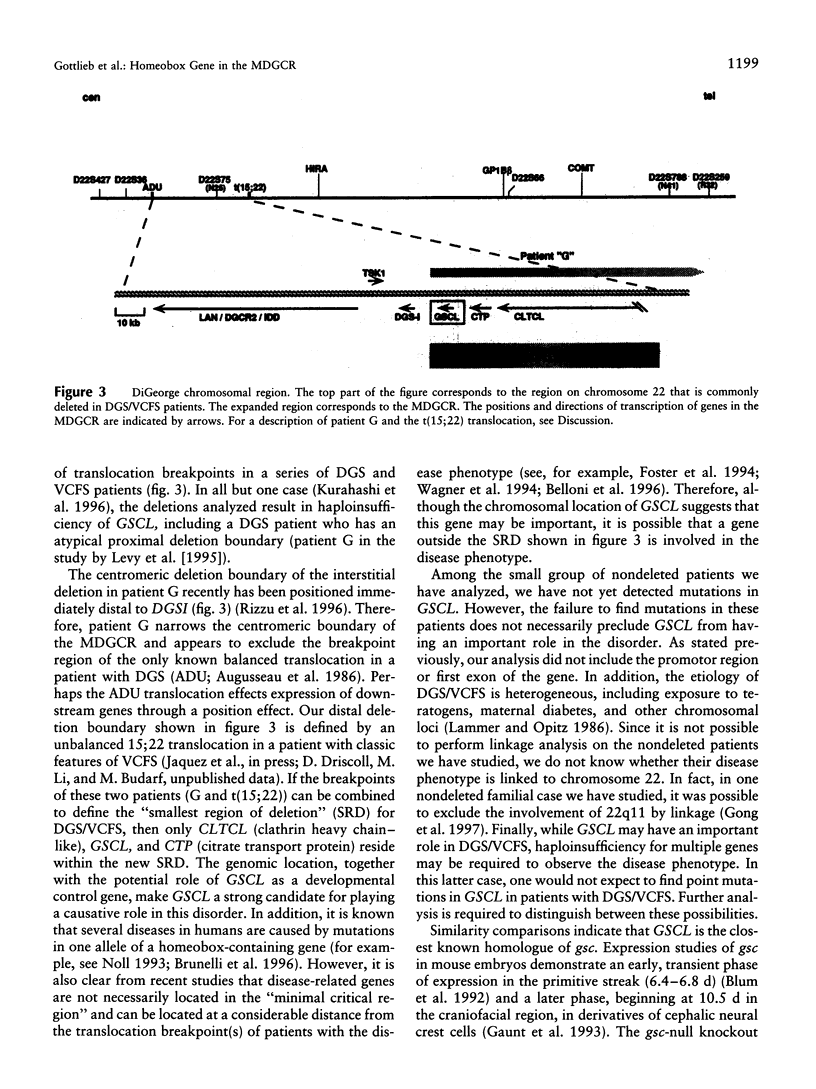

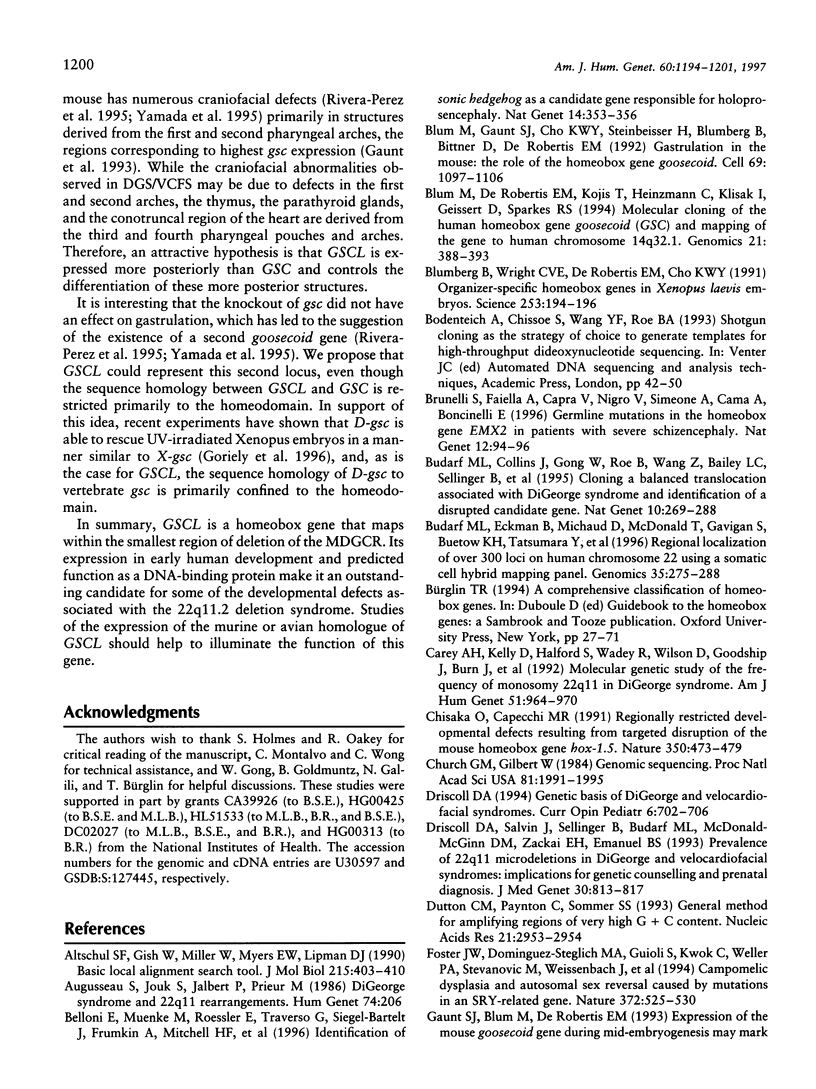

The majority of patients with DiGeorge syndrome (DGS) and velocardiofacial syndrome (VCFS) have deletions of chromosomal region 22q11.2. The abnormalities observed in these patients include conotruncal cardiac defects, thymic hypoplasia or aplasia, hypocalcemia, and characteristic facial features. To understand the genetic basis of these disorders, we have characterized genes within the region that is most consistently deleted in patients with DGS/VCFS, the minimal DiGeorge critical region (MDGCR). In this report, we present the identification and characterization of a novel gene, GSCL, in the MDGCR, with homology to the homeodomain family of transcription factors. Further, we provide evidence that this gene is expressed in a limited number of adult tissues as well as in early human development. The identification of GSCL required a genomic sequence-based approach because of its restricted expression and high GC content. The early expression, together with the known role of homeobox-containing proteins in development, make GSCL an outstanding candidate for some of the abnormalities seen in DGS/VCFS.

Full text

PDF

Images in this article

Selected References

These references are in PubMed. This may not be the complete list of references from this article.

- Altschul S. F., Gish W., Miller W., Myers E. W., Lipman D. J. Basic local alignment search tool. J Mol Biol. 1990 Oct 5;215(3):403–410. doi: 10.1016/S0022-2836(05)80360-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Augusseau S., Jouk S., Jalbert P., Prieur M. DiGeorge syndrome and 22q11 rearrangements. Hum Genet. 1986 Oct;74(2):206–206. doi: 10.1007/BF00282098. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Belloni E., Muenke M., Roessler E., Traverso G., Siegel-Bartelt J., Frumkin A., Mitchell H. F., Donis-Keller H., Helms C., Hing A. V. Identification of Sonic hedgehog as a candidate gene responsible for holoprosencephaly. Nat Genet. 1996 Nov;14(3):353–356. doi: 10.1038/ng1196-353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blum M., De Robertis E. M., Kojis T., Heinzmann C., Klisak I., Geissert D., Sparkes R. S. Molecular cloning of the human homeobox gene goosecoid (GSC) and mapping of the gene to human chromosome 14q32.1. Genomics. 1994 May 15;21(2):388–393. doi: 10.1006/geno.1994.1281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blum M., Gaunt S. J., Cho K. W., Steinbeisser H., Blumberg B., Bittner D., De Robertis E. M. Gastrulation in the mouse: the role of the homeobox gene goosecoid. Cell. 1992 Jun 26;69(7):1097–1106. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(92)90632-m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blumberg B., Wright C. V., De Robertis E. M., Cho K. W. Organizer-specific homeobox genes in Xenopus laevis embryos. Science. 1991 Jul 12;253(5016):194–196. doi: 10.1126/science.1677215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brunelli S., Faiella A., Capra V., Nigro V., Simeone A., Cama A., Boncinelli E. Germline mutations in the homeobox gene EMX2 in patients with severe schizencephaly. Nat Genet. 1996 Jan;12(1):94–96. doi: 10.1038/ng0196-94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Budarf M. L., Collins J., Gong W., Roe B., Wang Z., Bailey L. C., Sellinger B., Michaud D., Driscoll D. A., Emanuel B. S. Cloning a balanced translocation associated with DiGeorge syndrome and identification of a disrupted candidate gene. Nat Genet. 1995 Jul;10(3):269–278. doi: 10.1038/ng0795-269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Budarf M. L., Eckman B., Michaud D., McDonald T., Gavigan S., Buetow K. H., Tatsumura Y., Liu Z., Hilliard C., Driscoll D. Regional localization of over 300 loci on human chromosome 22 using a somatic cell hybrid mapping panel. Genomics. 1996 Jul 15;35(2):275–288. doi: 10.1006/geno.1996.0358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carey A. H., Kelly D., Halford S., Wadey R., Wilson D., Goodship J., Burn J., Paul T., Sharkey A., Dumanski J. Molecular genetic study of the frequency of monosomy 22q11 in DiGeorge syndrome. Am J Hum Genet. 1992 Nov;51(5):964–970. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chisaka O., Capecchi M. R. Regionally restricted developmental defects resulting from targeted disruption of the mouse homeobox gene hox-1.5. Nature. 1991 Apr 11;350(6318):473–479. doi: 10.1038/350473a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Church G. M., Gilbert W. Genomic sequencing. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1984 Apr;81(7):1991–1995. doi: 10.1073/pnas.81.7.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Driscoll D. A. Genetic basis of DiGeorge and velocardiofacial syndromes. Curr Opin Pediatr. 1994 Dec;6(6):702–706. doi: 10.1097/00008480-199412000-00016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Driscoll D. A., Salvin J., Sellinger B., Budarf M. L., McDonald-McGinn D. M., Zackai E. H., Emanuel B. S. Prevalence of 22q11 microdeletions in DiGeorge and velocardiofacial syndromes: implications for genetic counselling and prenatal diagnosis. J Med Genet. 1993 Oct;30(10):813–817. doi: 10.1136/jmg.30.10.813. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dutton C. M., Paynton C., Sommer S. S. General method for amplifying regions of very high G+C content. Nucleic Acids Res. 1993 Jun 25;21(12):2953–2954. doi: 10.1093/nar/21.12.2953. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foster J. W., Dominguez-Steglich M. A., Guioli S., Kwok C., Weller P. A., Stevanović M., Weissenbach J., Mansour S., Young I. D., Goodfellow P. N. Campomelic dysplasia and autosomal sex reversal caused by mutations in an SRY-related gene. Nature. 1994 Dec 8;372(6506):525–530. doi: 10.1038/372525a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gaunt S. J., Blum M., De Robertis E. M. Expression of the mouse goosecoid gene during mid-embryogenesis may mark mesenchymal cell lineages in the developing head, limbs and body wall. Development. 1993 Feb;117(2):769–778. doi: 10.1242/dev.117.2.769. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldmuntz E., Wang Z., Roe B. A., Budarf M. L. Cloning, genomic organization, and chromosomal localization of human citrate transport protein to the DiGeorge/velocardiofacial syndrome minimal critical region. Genomics. 1996 Apr 15;33(2):271–276. doi: 10.1006/geno.1996.0191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gong W., Emanuel B. S., Collins J., Kim D. H., Wang Z., Chen F., Zhang G., Roe B., Budarf M. L. A transcription map of the DiGeorge and velo-cardio-facial syndrome minimal critical region on 22q11. Hum Mol Genet. 1996 Jun;5(6):789–800. doi: 10.1093/hmg/5.6.789. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gong W., Emanuel B. S., Galili N., Kim D. H., Roe B., Driscoll D. A., Budarf M. L. Structural and mutational analysis of a conserved gene (DGSI) from the minimal DiGeorge syndrome critical region. Hum Mol Genet. 1997 Feb;6(2):267–276. doi: 10.1093/hmg/6.2.267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goriely A., Stella M., Coffinier C., Kessler D., Mailhos C., Dessain S., Desplan C. A functional homologue of goosecoid in Drosophila. Development. 1996 May;122(5):1641–1650. doi: 10.1242/dev.122.5.1641. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hanes S. D., Brent R. DNA specificity of the bicoid activator protein is determined by homeodomain recognition helix residue 9. Cell. 1989 Jun 30;57(7):1275–1283. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(89)90063-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hecht N. B. The making of a spermatozoon: a molecular perspective. Dev Genet. 1995;16(2):95–103. doi: 10.1002/dvg.1020160202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holmes S. E., Riazi M. A., Gong W., McDermid H. E., Sellinger B. T., Hua A., Chen F., Wang Z., Zhang G., Roe B. Disruption of the clathrin heavy chain-like gene (CLTCL) associated with features of DGS/VCFS: a balanced (21;22)(p12;q11) translocation. Hum Mol Genet. 1997 Mar;6(3):357–367. doi: 10.1093/hmg/6.3.357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kirby M. L., Bockman D. E. Neural crest and normal development: a new perspective. Anat Rec. 1984 May;209(1):1–6. doi: 10.1002/ar.1092090102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kirby M. L., Gale T. F., Stewart D. E. Neural crest cells contribute to normal aorticopulmonary septation. Science. 1983 Jun 3;220(4601):1059–1061. doi: 10.1126/science.6844926. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kozak M. Point mutations define a sequence flanking the AUG initiator codon that modulates translation by eukaryotic ribosomes. Cell. 1986 Jan 31;44(2):283–292. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(86)90762-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kurahashi H., Nakayama T., Osugi Y., Tsuda E., Masuno M., Imaizumi K., Kamiya T., Sano T., Okada S., Nishisho I. Deletion mapping of 22q11 in CATCH22 syndrome: identification of a second critical region. Am J Hum Genet. 1996 Jun;58(6):1377–1381. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kurihara Y., Kurihara H., Oda H., Maemura K., Nagai R., Ishikawa T., Yazaki Y. Aortic arch malformations and ventricular septal defect in mice deficient in endothelin-1. J Clin Invest. 1995 Jul;96(1):293–300. doi: 10.1172/JCI118033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kurihara Y., Kurihara H., Suzuki H., Kodama T., Maemura K., Nagai R., Oda H., Kuwaki T., Cao W. H., Kamada N. Elevated blood pressure and craniofacial abnormalities in mice deficient in endothelin-1. Nature. 1994 Apr 21;368(6473):703–710. doi: 10.1038/368703a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lammer E. J., Opitz J. M. The DiGeorge anomaly as a developmental field defect. Am J Med Genet Suppl. 1986;2:113–127. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.1320250615. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levy A., Demczuk S., Aurias A., Depétris D., Mattei M. G., Philip N. Interstitial 22q11 microdeletion excluding the ADU breakpoint in a patient with DiGeorge syndrome. Hum Mol Genet. 1995 Dec;4(12):2417–2419. doi: 10.1093/hmg/4.12.2417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Noll M. Evolution and role of Pax genes. Curr Opin Genet Dev. 1993 Aug;3(4):595–605. doi: 10.1016/0959-437x(93)90095-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rivera-Pérez J. A., Mallo M., Gendron-Maguire M., Gridley T., Behringer R. R. Goosecoid is not an essential component of the mouse gastrula organizer but is required for craniofacial and rib development. Development. 1995 Sep;121(9):3005–3012. doi: 10.1242/dev.121.9.3005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rizzu P., Lindsay E. A., Taylor C., O'Donnell H., Levy A., Scambler P., Baldini A. Cloning and comparative mapping of a gene from the commonly deleted region of DiGeorge and Velocardiofacial syndromes conserved in C. elegans. Mamm Genome. 1996 Sep;7(9):639–643. doi: 10.1007/s003359900197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rubin M. R., Toth L. E., Patel M. D., D'Eustachio P., Nguyen-Huu M. C. A mouse homeo box gene is expressed in spermatocytes and embryos. Science. 1986 Aug 8;233(4764):663–667. doi: 10.1126/science.3726554. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schorle H., Meier P., Buchert M., Jaenisch R., Mitchell P. J. Transcription factor AP-2 essential for cranial closure and craniofacial development. Nature. 1996 May 16;381(6579):235–238. doi: 10.1038/381235a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shackleford G. M., Varmus H. E. Expression of the proto-oncogene int-1 is restricted to postmeiotic male germ cells and the neural tube of mid-gestational embryos. Cell. 1987 Jul 3;50(1):89–95. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(87)90665-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith S. T., Jaynes J. B. A conserved region of engrailed, shared among all en-, gsc-, Nk1-, Nk2- and msh-class homeoproteins, mediates active transcriptional repression in vivo. Development. 1996 Oct;122(10):3141–3150. doi: 10.1242/dev.122.10.3141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Treisman J., Gönczy P., Vashishtha M., Harris E., Desplan C. A single amino acid can determine the DNA binding specificity of homeodomain proteins. Cell. 1989 Nov 3;59(3):553–562. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(89)90038-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Uberbacher E. C., Mural R. J. Locating protein-coding regions in human DNA sequences by a multiple sensor-neural network approach. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1991 Dec 15;88(24):11261–11265. doi: 10.1073/pnas.88.24.11261. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wagner T., Wirth J., Meyer J., Zabel B., Held M., Zimmer J., Pasantes J., Bricarelli F. D., Keutel J., Hustert E. Autosomal sex reversal and campomelic dysplasia are caused by mutations in and around the SRY-related gene SOX9. Cell. 1994 Dec 16;79(6):1111–1120. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(94)90041-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woodford K., Weitzmann M. N., Usdin K. The use of K(+)-free buffers eliminates a common cause of premature chain termination in PCR and PCR sequencing. Nucleic Acids Res. 1995 Feb 11;23(3):539–539. doi: 10.1093/nar/23.3.539. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Worley K. C., Wiese B. A., Smith R. F. BEAUTY: an enhanced BLAST-based search tool that integrates multiple biological information resources into sequence similarity search results. Genome Res. 1995 Sep;5(2):173–184. doi: 10.1101/gr.5.2.173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamada G., Mansouri A., Torres M., Stuart E. T., Blum M., Schultz M., De Robertis E. M., Gruss P. Targeted mutation of the murine goosecoid gene results in craniofacial defects and neonatal death. Development. 1995 Sep;121(9):2917–2922. doi: 10.1242/dev.121.9.2917. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang J., Hagopian-Donaldson S., Serbedzija G., Elsemore J., Plehn-Dujowich D., McMahon A. P., Flavell R. A., Williams T. Neural tube, skeletal and body wall defects in mice lacking transcription factor AP-2. Nature. 1996 May 16;381(6579):238–241. doi: 10.1038/381238a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]