Abstract

This article examines the role of the California Health Benefits Review Program (CHBRP) as a source of information in state health policy making. It explains why the California benefits review process relies heavily on university-based researchers and employs a broad set of criteria for review, which set it apart from similar programs in other states. It then analyzes the politics of health insurance mandates and how independent research and analysis might alter the perceived benefits and costs of health insurance mandates and thus political outcomes. It considers how research and analysis is typically used by policy makers, and illustrates how participants inside and outside of state government have used the reports prepared by CHBRP as both guidance in policy design and as political ammunition. Although there is consensus that the review process has reduced the number of mandate bills that are passed out of the legislature, both supporters and opponents favor the new process and generally believe the reports strengthen their case in legislative debates over health insurance mandates. The role of the CHBRP is narrowly defined by statute at the present time, but the program may well face pressure to evolve from its current academic orientation into a more interactive, advisory role for legislators in the future.

Keywords: State health policy, health insurance, politics, legislative decision making

The great significance of the growing role of experts in the democratic process is not, as is often feared, their ability to manipulate elected representatives and gain irresponsible control over the routine operations of public bureaucracies, but rather their ability to provide the intellectual underpinnings of public policy (Walker 1981, p. 93).

Information and analysis constitute only one route among several to social problem solving (Lindblom and Cohen 1979, p. 12).

The purpose of this article is to examine the role of the California Health Benefits Review Program (CHBRP) as a source of information in state health policy making. The article reviews the circumstances under which state officials established CHBRP and the organizational structure that emerged under the auspices of the University of California. It then explains the political nature of health insurance mandates and how independent research and analysis might alter the politics of policy making in this area. It reports how various participants inside and outside of state government have used the analyses prepared by CHBRP, and the impact they perceive on the policy process. Finally, it identifies some of the challenges that CHBRP faces or might face in the near future as it refines its role and responds to state policy makers.

THE ORIGINS OF THE CHBRP

The CHBRP was established by the University of California in response to Assembly Bill 1996 (AB 1996), enacted in 2002 (California Health and Safety Code, Section 127660, et seq.). One might expect health benefits review organizations to originate in state governments dominated by Republicans wishing to protect the prerogatives of employers and insurance companies, promote consumer choice of benefits packages, and curtail the growth of governmental regulation and its presumed contribution to the rising costs of health care. In California, however, AB 1996 was enacted by a legislature with large Democratic majorities in both houses and it was signed by a Democratic governor who had approved a host of new mandates for managed care plans. The origins and design of CHBRP illustrate how debates over health insurance mandates cannot easily be reduced to “proconsumer” and “probusiness” positions, and how a benefits review program can be supported by a variety of groups across the political spectrum.

As a nationwide “backlash” against managed care took form in the late 1990s (Rochefort 2001), the California Legislature considered dozens of bills each year to regulate the management practices and scope of health plan coverage (65 in 1997 and more than 100 in 1999, by one count). In 1996, legislators approved AB 2343, introduced by Assemblyman Bernie Richter (R), which established a California Managed Health Care Improvement Task Force. Governor Pete Wilson (R) signed the bill and appointed 20 of the 30 members on the task force, which convened in 1997. In January 1998, the task force issued a number of recommendations that served as the basis for new managed care reforms, including an expansion of mandated benefits (Aubry and Alpert 1998; MHCITF 1998; Schauffler et al. 2001).

Wilson subsequently signed a number of bills that mandated coverage for very specialized procedures or populations. Most of the new mandates were imposed on health care service plans—large HMOs and PPOs—that were licensed and regulated under the provisions of the Knox–Keene Act by the California Department of Corporations. Others were aimed at health insurers, mostly smaller PPOs that operated under a different set of regulations administered by the California Department of Insurance. Ten separate bills were enacted in 1998 alone and Wilson's case-by-case approval signaled legislators that they might successfully enact additional mandates as long as the new measures were tightly drawn (IG interview; AA interview).

After Gray Davis was elected in November 1998—the state's first Democratic governor in 16 years—he signed an additional seven mandate bills in his first year in office. Among other provisions, they guaranteed second medical opinions, established coverage of severe mental illness on par with other benefits, and required coverage for specific services ranging from cancer screening to diabetes management to contraceptives (CHBRP mimeo). New legislation also shifted regulation of large health care service plans from the Department of Corporations to a new Department of Managed Health Care.

The health benefits review process authorized in AB 1996 evolved from several sets of concerns. Even as the economy declined after 2000—exacerbated in California by the “dot.com bust”—legislators continued to introduce a steady stream of proposed new health insurance mandates. Health plans sought ways to limit the growth of mandates. Whereas their leaders recognized the value of the individual services to some of their customers, they adopted a principled stand against all proposed mandates on the grounds that they limited the flexibility of their administrative and clinical practices, and restricted desirable variation in health insurance products and consumer choice in the marketplace (IG interviews). As health care costs began rising rapidly again in the late 1990s, employers and public officials became more concerned with legislation that might, even marginally, make insurance premiums less affordable and lead firms and individuals to drop their existing coverage. Finally, it was clear even to liberal, proconsumer activists that many of the proposed mandates, including coverage for specific tests and for vaccines that did not even exist, were bad public policy, merely establishing economic benefits for particular companies or industries at the expense of the general public (IG interview). Furthermore, as the Knox–Keene rules required health plans to provide all medically necessary care, the wave of new mandates in some respects posed a threat to that clinical, consumer orientation. An ever-expanding set of line-item mandates might call into question whether particular services or health conditions that were not explicitly mandated were in fact medically necessary (AA interview).

In early 2002, there were more than a dozen mandate bills pending. The California Association of Health Plans sponsored a bill (AB 1801) introduced by Assemblyman Robert Pacheco (R) to establish a “Commission on Health Care Cost Review” to review proposed health benefits mandates and other legislation affecting health care service plans, as well as other public policies affecting health care costs and access to insurance coverage in California. The bill sketched only in brief detail a small independent commission with five political appointees, and a review process focused on the costs of new mandates and their impact on the uninsured (Assembly Committee on Health 2002; IG interview; LS interview). Also sensing a need for more systematic evaluation, Democratic leaders in the key health committees agreed to institute a moratorium on all bills calling for new health insurance mandates while they considered alternative methods of review. A legislative staffer recalls the thinking at the time: “Legislative bodies are not good forums for deciding clinical issues. … We need a better way to deal with this. All the arguments are the same: all of these are needed and won't cost much. We had no way to assess to what extent they're needed and how much they will cost, to help us differentiate among the bills. We wanted a more rational, thoughtful, deliberative way to look at these bills” (LS interview). A health plan representative agreed: “My sense is that legislators got tired of running around in striped shirts with a whistle around their neck” (IG interview).

Helen Thomson (D), then chair of the Assembly Committee on Health, took the lead and drafted a new version of AB 1996, which started out as a bill to expand prescription drug coverage. Her bill also sought to establish a commission, but broadened the scope of representation with greater roles for labor, consumer organizations, and academic experts. It also introduced much more expansive criteria for review, suggesting a focus on public health impact (i.e., health status, access to care) and medical effectiveness as well as costs (IG interview). According to one researcher, Minnesota was the only state at the time that required analysis of the public health impact of proposed mandates (UR interview).

After its passage in the Assembly, AB 1996 was considered in the Senate Committee on Insurance (now the Senate Committee on Banking, Finance, and Insurance). It failed initially because of concerns about setting up another new bureaucracy, and that a commission holding its own public hearings might usurp legislative decision making. It was then reconsidered, however, and Senator Jackie Speier (D) suggested an amendment to change the organizational structure of the review process. Instead of creating a new independent commission, Senator Speier recommended assigning the review program to the University of California (LS interview; UR interview; IG interview). The university is the constitutionally established research arm for state government, and has a number of units that either administer independent research or produce analysis and reports themselves in areas relevant to public policy (UCOP interview; UR interview). This amendment was adopted in the Senate and accepted by the Assembly in the final statute. This change helped set California's approach apart from what other states have done in this area of health policy.

Once AB 1996 was enacted, the task of conducting health benefits review was assigned to the University of California Office of the President and, specifically, to its Division of Health Affairs. The university had concerns regarding this role, the principal one being that as a major employer offering health benefits and as a major provider of health services through its medical centers, it would potentially have considerable financial stakes of its own in the outcome of mandate proposals. This was addressed by creating a “firewall” within the Office of the President, so that the officials responsible for negotiating the university system's health benefits and those protecting and promoting the academic medical centers were prohibited from directly communicating with CHBRP staff about their analyses or methods, and vice versa (UCOP interviews).

The university's vice president for health affairs initially considered a recommendation to hire a sizable number of full-time professional staff, who could conduct all aspects of the research and analysis required by the legislature. He saw an opportunity to establish a different structure, however, which would serve each of the university's principal missions of research, education, and public service. After consulting with faculty who were actively involved and interested in health insurance issues, he concluded that it would be feasible and desirable to delegate some of CHBRP's work to university campuses. This could make it more difficult to complete reviews in the 60-day window required under AB 1996, but it had two key advantages. First, it would demonstrate to policy makers and outside stakeholders that the reports CHBRP issued were produced by individuals with high academic reputations, an important element in establishing political credibility. As one academic contributor to the reports noted, the CHBRP could contract out this work to private consultants and end up with a report that was packaged nicely but was not as thorough or independent (UR interview). Second, it would provide an opportunity for university faculty, postdoctoral fellows, and students to directly contribute their expertise to officials, and also to become more familiar with the challenges of formulating public policy in this complex area (UR interviews; UCOP interviews).

Eventually, it was agreed to have most of the technical analysis for CHBRP done by researchers in the schools of medicine and public health throughout the state, both within the University of California system and private institutions. A small full-time group of expert analysts within the Division of Health Affairs would coordinate the research activities on different campuses, add specific elements to each review, oversee the writing and final production of CHBRP reports, and serve as the point of contact and ongoing communication with the legislature. To further add credibility to its analyses and obtain input from stakeholders who were not directly affected by the proposed mandates, CHBRP recruited a national advisory council of independent experts and representatives of health plans, purchasers, providers, and consumer groups and actively involved them in the final review and preparation of its reports to the legislature (UCOP interviews).

HOW CHBRP COMPARES WITH OTHER STATE HEALTH BENEFITS REVIEW PROGRAMS

As of 2004, 29 states have established a formal health benefits review process in law for one or more segments of the health insurance market (see Table 1).1 California is unique in setting up a new institutional structure within a public university system. Many states require another existing governmental entity to review health insurance mandates. This task is assigned to the department of insurance in eight states, to the office of legislative services in seven states, and to another executive agency in four states.

Table 1.

Institutional Structure of State Health Benefits Review Programs

| State* | Commission† | Department of Insurance‡ | Legislative Services§ | Sponsors¶ | Other State Agency∥ | University |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Arizona | ✓ | |||||

| Arkansas | ✓ | |||||

| California | ✓ | |||||

| Colorado** | ✓ | ✓ | ||||

| Florida | ✓ | |||||

| Georgia | ✓ | |||||

| Hawaii†† | ✓ | |||||

| Indiana‡‡ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||

| Kansas | ✓ | |||||

| Kentucky | ✓ | |||||

| Louisiana | ✓ | |||||

| Maine | ✓ | |||||

| Maryland | ✓ | |||||

| Massachusetts | ✓ | |||||

| Minnesota | ✓ | |||||

| Nevada§§ | ✓ | |||||

| New Hampshire | ✓ | |||||

| New Jersey | ✓ | |||||

| North Carolina | ✓ | |||||

| North Dakota | ✓ | |||||

| Ohio | ✓ | |||||

| Pennsylvania | ✓ | |||||

| South Carolina | ✓ | |||||

| Tennessee | ✓ | |||||

| Texas | ✓ | |||||

| Utah | ✓ | |||||

| Virginia | ✓ | |||||

| Washington | ✓ | |||||

| Wisconsin | ✓ |

States listed here have a formal mandate evaluation program or process; or they have a law requiring evaluation of health insurance mandate bills by sponsors of a bill.

Commission-based programs usually consist of individuals appointed by the executive branch and the legislative branch and represent different industry and consumer interests. Commissions that evaluate health insurance benefits often conduct other types of analysis related to health care programs in the state.

“Department of Insurance” programs includes the “Insurance Commissioner,”“Office of Insurance,” or the equivalent agency in that respective state. These are housed in the executive branch of the state government.

“Legislative Services” programs include those that are housed at the departments or agencies designed to support the state legislature.

The requirement for conducting evaluations falls primarily on the bill sponsors. Sponsors may mean a member of the state legislature but usually mean an outside organization or association advocating for passage of the bill.

“Other State Agency” programs include those that are housed at another agency under the executive branch besides the Department of Insurance.

Colorado has two separate laws: One creates a mandate evaluation commission that is to sunset in May 2005 and another law requires any sponsor of a legislation to provide a “social” and “financial” impact analysis of the proposal to the legislative committee with jurisdiction.

Hawaii's mandate evaluation is conducted by the State Auditor, who reports to and is considered part of the legislative branch.

Indiana has a “Mandate Health Benefit Task Force” whose members are appointed by the governor and is staffed by the Insurance Commissioner.

Nevada's legislature passed two concurrent resolutions to study (1) the cost of existing mandates (1990) and (2) whether any existing mandates ought to be repealed (1992). Both of these were conducted by subcommittees appointed by the Legislative Commission.

Note: Those states listed here are different from those listed in Bellows et al, in this issue. Bellows and colleagues examine the characteristics of state laws that have established mandate review evaluation programs in the U.S. This article summarizes information gathered by CHBRP through interviews with officials in each state. Differences between laws that authorize mandate evaluation programs and the actual program implementation occur for several reasons: (1) there has not been enough time to develop a program or process in compliance with the new law; (2) the laws do not always explicitly dictate the criteria and steps for mandate evaluations. The implementation of such laws and policies are subject to interpretation, therefore, and can vary from time to time (for example, with changes in administration); or (3) state governments and their various departments do not always uniformly implement laws related to mandate evaluation programs or processes even when criteria and steps for evaluations are explicitly defined. This may occur due to several reasons, including limits on data availability, limits on staff and funding, or the political climate in the state.

Eight states have opted to set up independent commissions, task forces, or advisory committees. They vary in their charge, structure, and staffing but most have members who are appointed by the governor and the legislature and who represent a cross-section of interests from the health care industry, business, and consumer groups. Six of those commissions are set up specifically to evaluate health insurance mandates. The remaining two, the Maryland Health Care Commission and the Pennsylvania Health Care Cost Containment Council, are charged with reviewing proposed health insurance mandates in addition to their other responsibilities. For example, the Maryland commission oversees the state's small group health insurance market and is responsible for modifying existing coverage in its Comprehensive Standard Health Benefit Plan to keep premiums below a mandatory cost ceiling (MHCC 2003).

Three states place primary responsibility on the sponsor of a proposed mandate for providing analysis to the legislature. The sponsor may be defined as a member of the legislature, an organization, an interest group, or individual depending on the state. This approach results in substantial variation in the scope, application of evaluation criteria, and overall quality of the review; and legislative committees may move forward with hearings and votes even if an analysis has not been submitted.

Few state programs have as broad a set of criteria for evaluating proposed mandates as California. The programs located in insurance departments are generally charged with examining only the cost impact of a proposed mandate on the commercial health insurance market. In Washington State, the health department is required to conduct an analysis similar in scope to CHBRP, reviewing medical effectiveness, financial impact, the extent to which a mandated benefit will enhance the general health status of state residents, and the overall cost–benefit ratio (RCW 48.47.030; WDH 1999). Up until 2003, Maryland's commission was required to review the fiscal, social, and medical impact of proposed mandates that did not pass during the prior legislative session. The provisions of House Bill 605 now require the commission to conduct studies of each existing mandated benefit, including its costs, the degree to which it is covered under self-insured plans in the state, and whether it is mandated in neighboring states as well (Maryland Code Ann., Insurance, Sec. 15–1502 [2003]). The commission must then make recommendations on how to reduce the number of mandates or the extent of coverage under those that now exist.

The creation of most if not all state review programs, with their heavy emphasis on financial costs, reflects a skeptical view of insurance mandates and places additional burdens on advocates of new mandates. The programs in California and Washington put the costs of mandated services into a broader context of public health improvement, and it is that feature more than any other that other states would do well to emulate.

THE POLITICAL NATURE OF HEALTH INSURANCE MANDATES

As the articles elsewhere in this issue demonstrate, the review of proposed health insurance mandates is a highly technocratic exercise (Halpin et al. 2006; Kominski et al. 2006; Luft et al. 2006; McMenamin, Halpin, and Ganiats 2006). It is produced and debated within a small, specialized group of policy professionals occupying positions inside and outside of government, often referred to as an issue network or policy community (Heclo 1978; Walker 1981; Kingdon 1984; Whiteman 1987). The activity of government in this area is virtually invisible to the general public, as governors, party leaders, and the mass media focus on broader policy initiatives. Information and expertise may shape decisions within this area of health policy, but the sponsors of the proposal, the image of the intended beneficiaries, the presence of organized opposition, and the venue for decision making all matter as well. All the evidence suggests that health benefits review organizations such as CHBRP operate within a decision-making process that is highly political, where analysis supplied by technical experts must compete with the energy and strategic activities of individuals and organizations with a vested interest in the outcome.

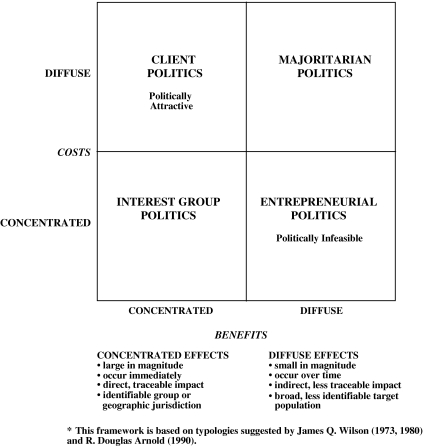

In the case of health insurance mandates, what makes them so politically attractive is that they usually promise desirable benefits for relatively few people at little or no cost to everyone else (LS interview; IG interviews). This seems counterintuitive, if one thinks of politics as amassing the greatest number of supporters, but it is consistent with the logic of legislative decision making advanced by Wilson (1973, 1980) and Arnold (1990), as represented in Figure 1. Laugesen et al. (2006) point to the example of mandated coverage for special formulas for infants with the metabolic disorder phenylketonuria, which affects an estimated one in 14,000 babies.

Figure 1.

Framework for Analysis of Policy Design and Political Feasibility

On the surface, almost all new coverage mandates appear to take the form of “client politics,” the most politically feasible environment for policy change. Client politics emerge when existing policies or proposals for new policies offer relatively concentrated benefits—large, direct, and immediate assistance for an identifiable group of health care patients, providers, manufacturers, or insurers—while imposing only diffuse costs across all insured individuals or taxpayers. The reason proposals that involve client politics are so numerous and successful is that they create loyal, mobilized supporters, and attract very little organized opposition. This imbalance creates the conditions under which “politics trumps science” when proposed mandates are not carefully scrutinized (Schauffler 2000; Weiss 2004). Even political “clients” who are not especially well-organized can be successful if they have a positive public image and voters and politicians view them as deserving of assistance (Schneider and Ingram 1993).

In 2004, two of the four mandate bills that passed both houses of the California Legislature were intended to benefit children with chronic health problems, either suffering from asthma (AB 2185) or hearing impairments (SB 1158). A third, SB 1555, was intended to ensure that the small fraction of insurance policies sold in the state that did not cover prenatal care and hospital delivery of newborns would now be required to do so. The fourth, SB 1157, was intended to prohibit health insurers from denying coverage for treatment if the policyholder was found to be intoxicated or under the influence of controlled substances. In 2005, three mandate bills were passed out of the legislature. One sought to require plans to ensure that patients infected with HIV had the same level of access to transplantation surgery as other patients (AB 228). Another, SB 573, was the same bill as SB 1157 that passed the previous year (prohibiting coverage denials based on intoxication).

Each of these bills pursued concentrated benefits for deserving beneficiaries accompanied by very diffuse costs, at least from a systemwide perspective. For example, across the segments of the health insurance market affected by the mandates, the net increase in total premiums per member per month ranged from zero for transplantation for HIV-positive patients and treatment of intoxicated patients; from $0.008 to $0.019 for childhood asthma management; and from $0.07 to $0.11 for hearing aids for children. Using even the highest estimate, the average premium would increase by only $1.32 per year (CHBRP 2004a, b, c; 2005a, b).

Yet an apparently favorable distribution of perceived benefits and costs is by no means fixed; it can be altered by individuals and organizations that are able to define and document new benefits or costs (Oliver 1996; Oliver and Paul-Shaheen 1997). To the degree that the burdens of a new health insurance mandate are perceived to be concentrated on particular providers, insurers, or purchasers of insurance, then policy making shifts from an environment of client politics to “interest group politics.” In this environment, both benefits and costs are relatively concentrated and this creates much greater conflict, which makes elected officials far more reluctant to intervene (as they routinely search for consensus and attempt to avoid issues on which there is disagreement either among experts or important constituencies) (Kingdon 1977, pp. 574–79; Kingdon 1984, pp. 157–59).

It can be argued that interest group politics created problems for at least one of the mandate proposals in 2004. The CHBRP estimated that two percent of Californians with private insurance did not have maternity benefits, and SB 1555 would have guaranteed that coverage for an additional 240,000 beneficiaries in the individual insurance market. But SB 1555 pitted several large health plans against each other. The proposed mandate was initiated and sponsored by Kaiser Permanente and Blue Shield of California, in fact, and aimed at one of their chief rivals, California Blue Cross, which marketed some of the less comprehensive plans to individuals and small businesses. The CHBRP report on SB 1555 indicated other forms of concentrated costs as well: the costs of requiring all plans to cover maternity services would have been negligible (3 cents per insured per month) for the market as a whole, but the mandate was expected to increase premiums by 13 percent for policyholders between 25 and 39 years of age who currently purchase plans without maternity coverage in the individual insurance market. Opponents seized not only on the projected increase in premiums for this segment of the market but even more on the estimate that almost 1,900 currently insured individuals might become uninsured, with only 227 picked up by Medi-Cal or Healthy Families (CHBRP 2004c, p. 3). It was this small increase in the projected number of uninsured that became the focal point for health plans' opposition and for Governor Schwarzenegger's message when he vetoed SB 1555 (IG interview; GS interview; Schwarzenegger 2004).

In 2005, it can be argued that “entrepreneurial politics”—where concentrated costs are imposed on a small number of providers, organizations, or individuals in order to generate diffuse benefits—led to the demise of the SB 576, a bill that would have mandated coverage for tobacco cessation treatment. The public health benefits of tobacco cessation have been documented over the last several years (U.S. DHHS 2004). There are real short-term benefits for quitting smoking that accrue to both an individual enrollee and health plan. However, most of the benefits accrue over the longer term, and some of the savings associated with the prevention of certain types of cancers, emphysema, and other pulmonary diseases may be distributed among future health care purchasers (including Medicare), the broader health care system, and society as a whole. The CHBRP analysis quantified the short-term savings of tobacco cessation in terms of the reduction in heart attacks and low-birthweight deliveries; the per member per month premium estimate, however, did not account for the longer term savings associated with reduction in other tobacco-related diseases (CHBRP 2005c). While the analysis summarized the public health literature quantifying long-term savings reaped by the health care system and public purchasers (e.g., Medi-Cal), it did not translate those savings into immediate premium impacts. Thus the benefits were smaller, less immediate, and accrued to less identifiable beneficiaries than the immediate premium increases to cover the costs of smoking cessation services, which fell upon readily identifiable businesses such as health plans and employers (especially small group), as well as individual policyholders. Thus, the combination of concentrated costs and diffuse benefits may have contributed to Governor Schwarzenegger's veto of the legislation. A list of supporters and opponents of the bill in Table 2 illustrates this distribution of interests and political mobilization.

Table 2.

Organized Interests on SB 576 Mandated Coverage of Tobacco Cessation

| Support (as of 9/2/05) | Opposition (as of 9/2/05) |

|---|---|

| American Cancer Society (co-source) | Association of California Life and Health Insurance Agencies |

| California Tobacco Control Alliance (co-source) | |

| American Federation of State, County and Municipal Employees | Blue Cross of California |

| American Heart Association | California Association of Health Plans |

| American Lung Association | California Association of Physician Groups |

| American Lung Association of Sacramento-Emigrant Trails | California Chamber of Commerce |

| Association of Northern California Oncologists | California Restaurant Association |

| Bay Area Community Resources | Health Net |

| Breast Cancer Fund | Kaiser Permanente |

| BUILT (State Building and Trades Council Project) | Specialty Health Plans |

| California Medical Association | |

| California Psychological Association | |

| California Thoracic Society | |

| Center for Tobacco Cessation | |

| Integrating Medicine and Public Health Program | |

| Latino Issues Forum | |

| San Luis Obispo County Tobacco Control Coalition | |

| Smoke Free Marin Coalition | |

The proposed mandates for maternity coverage and smoking cessation illustrate the political and moral dilemma confronting policy makers who attempt marginal adjustments within a fragmented system of health insurance. The chief problem is not the net cost to society as a whole but rather that society does not distribute the costs of the coverage broadly enough among its members. Instead, it allows the new costs to fall entirely on holders of less comprehensive policies, who are likely already in less fortunate economic circumstances. To the extent that health insurance is based on the principle of “actuarial fairness” rather than the principle of “social solidarity,” even the most sensible efforts to expand coverage risk defeat without the means to fairly distribute the new costs (Stone 1993; Oliver 1999).

With the exception of mandates for preventive services, such as tobacco cessation, the CHBRP generally does not have to confront the hazards of “entrepreneurial politics” in pursuit of better quality of care or financial savings for the general population. The program avoids sharp controversy as under the current statute the legislature asks it to review only proposed new health insurance mandates, not existing ones. This is the political challenge faced by the Oregon Health Services Commission, which must periodically review and recommend changes in the state's priority list of covered health services for Medicaid; by the Maryland Health Care Commission, which must review and recommend changes to the state's Comprehensive Standard Health Benefit Plan for small group insurance; and by administrators of private health plans such as Blue Shield of California, which periodically decide to drop coverage for services no longer considered to be state-of-the-art. The federal Agency for Health Care Policy and Research, now the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, was nearly terminated in the mid-1990s after it released its evidence-based practice guidelines that recommended that individuals suffering low-back pain first try extended bed-rest before choosing to proceed with back surgery (Deyo et al. 1997; Stryer et al. 2000; Gray, Gusmano, and Collins 2003; Gaus 2003). The problem in applying even the best evidence-based research to policy in these circumstances is that the cost savings are spread broadly and future beneficiaries of higher quality services are unaware of their good fortune, while the providers and patients for whom services are no longer recommended or paid for are well aware of the immediate threat to their well-being. Not surprisingly, it is far easier to mobilize people who have something to lose than those who have something to gain (Arnold 1990).

It is the role of “policy entrepreneurs” and their supporters to create more concentrated benefits (by making them more tangible and immediate) and dilute the anticipated costs (by easing economic, procedural, or symbolic burdens) of their legislative proposals. Conversely, opponents strive to minimize the benefits and identify more concentrated costs (Oliver and Paul-Shaheen 1997, p. 754). Legislators do not need analysis to identify potential winners and losers associated with proposed health insurance mandates. Proponents usually argue that the services they recommend for coverage are beneficial for patients and may even reduce costs. Opponents typically argue that, if the services were beneficial, they would already be offered by most plans. Alternatively, they may concede that the benefit has some value but is not worth the added cost for employers or beneficiaries with limited budgets for health insurance, and a mandate may lead them to forego health insurance entirely.

This conceptual approach suggests why, from a purely political perspective, the work of CHBRP might be influential in state policy making: By more accurately defining the general types of benefits and costs associated with health insurance mandates, organizations like CHBRP help establish the terms of the political debate. By documenting the specific benefits and costs associated with a particular health insurance mandate, CHBRP research and analysis can alter the balance of perceived benefits and costs and thus alter the prospects for successful enactment and implementation of that proposal. For example, in 2005 CHBRP analyzed a bill that would mandate a specific length of stay in the hospital for women undergoing a mastectomy or lymph node dissection for the treatment of breast cancer (CHBRP 2005d). This bill was a marginal change from current law in that it mandated stays of 48 hours after a mastectomy and 24 hours after a lymph node dissection. The CHBRP analysis indicated that, holding risk factors constant, patients undergoing mastectomy or lymph node dissection had comparable outcomes whether they received treatment in an inpatient or outpatient setting. The analysis did not support an argument that there were substantial benefits in terms of medical outcomes or public health impact. Furthermore, there was no clear organizational sponsor for the bill. As certain health plans would have opposed the bill's more stringent hospitalization standards, the author of the bill ultimately decided not to pursue the legislation.

LESSONS FROM THE LITERATURE ON RESEARCH UTILIZATION

Despite the political implications of their work, the program staff at CHBRP and the contributing academic researchers are not seeking to wield power, but rather to “speak truth to power” and assist in the formulation of good public policy (Wildavsky 1979). In their view, state health benefits review programs should serve as a source of objective information and transparent analysis.

This view reflects both caution and a realistic assessment of the limits of health services research. Independent research and analysis is only one source of information in the legislative process. Lindblom and Cohen (1979) argue that the dominant source of information used to solve social problems is not professional social inquiry, but instead “ordinary knowledge:”

By ‘ordinary knowledge,’ we mean knowledge that does not owe its origin, testing, degree of verification, truth status, or currency to distinctive professional techniques but rather to common sense, casual empiricism, or thoughtful speculation and analysis. … [A]lthough [practitioners of professional social inquiry] possess a great amount of relatively high-quality ordinary knowledge, so do many journalists, civil servants, businessmen, interest-group leaders, public opinion leaders, and elected officials (Lindblom and Cohen 1979, p. 13).

If the ordinary knowledge of policy makers and staff focuses on the intrinsic value of personal health care, then the role of expert research and analysis is to raise other questions: is this type of care effective and for whom, is it currently unavailable to many patients and if so why, who would bear the costs of added coverage, and what impact might there be on the broader system of health care? These questions create a more complex scheme for political judgment and, even if officials are principled supporters or opponents of mandates, the answers to those questions can help them gauge what mandates should have priority over others. CHBRP reports fall into the category of what MacRae and Whittington (1997, Chapter 1) call “preparatory advice” for policy making: they include careful description of health care conditions and projection by modeling the impact of legislative proposals. Although the reports make no policy recommendations themselves, they may improve public discourse and serve as the basis for the recommendations of others in the policy process.

The primary users of independent research and analysis are largely determined by the institutional context of legislative decision making. Most of the personal staff for legislators cover a wide range of issues and often dozens of bills, so they are under severe time constraints and keeping up with social and scientific research is a “dispensable luxury” (Weiss 1989, p. 413). They generally track bills through committee hearings, legislative staff analysis, and meetings with interest groups and constituents. Their chief responsibilities are to brief their members with basic facts and questions for hearings, mark-ups, and floor votes, prepare possible amendments, and communicate similarly basic information to other legislative staff who must answer constituent inquiries. Only if a member decides to get more involved on an issue—usually by introducing a bill—will personal staff seek out detailed research and analysis. Making health services research accessible to personal staff is further complicated by the fact that almost none of them have formal academic training or professional experience in the health field. Committee staff usually include individuals who have such training or experience and are able to focus exclusively on health issues, but on a given policy, budget, or appropriations committee there are usually only one or two staffers who are responsible for a given bill and other related legislation (Whiteman 1987, pp. 222–4).

So the potential audience for sophisticated health services research inside the legislature is extraordinarily small, yet that audience is intensely interested in relevant research products. In an extensive study of congressional staffers, Whiteman (1987, p. 225) finds:

The staff most involved in formulating policy on an issue tend to develop expertise by drawing upon a broad spectrum of relevant information—including policy analyses sponsored by congressional support agencies, executive branch agencies, and various public and private policy research organizations; expert advice provided by a host of academics, consultants, executive branch personnel, and interest group representatives; and practical and political advice from members of affected groups.

The dependence of the “inner core” of committee staff on the type of research and analysis produced by CHBRP is all the greater because of rapid staff turnover. In California, where members face term limits of 6 years in the Assembly and 8 years in the Senate, committee chairs and members change rapidly and, in particular, a new chair commonly brings in a new lead staffer to manage the committee's work. Even though staff may have worked on health insurance issues for other members and other committees, their roles as advisors and managers are in constant flux. The downside to turnover among legislators is a depletion of both expertise and institutional memory: they will have to learn the nuances of a policy issue before they are prepared to appropriately use many research findings. Sorian and Baugh (2002, p. 270) report that legislators and legislative staff turn most frequently to state agencies for information on policy issues and, in the context of term limits in California, reliance on a stable source of information like CHBRP would presumably increase.

The use of research in the policy process ranges from direct and immediate implementation of a study's recommendations to a gradual shift in thinking over the course of many years. Weiss (1977, 1989) identifies four functions of research and analysis in the policy process: warning, guidance, ammunition, and enlightenment. Research serves as a warning when it brings attention to a problem that has not been widely recognized, or to a sudden change in conditions. In the world of health insurance, for example, surveys and other research commonly focus policy makers on rising costs and changes in the number or types of persons who are uninsured.

Much of the literature examines how unsolicited research and analysis produced by academics, think tanks, and interest groups influences policy, if at all. In many situations, however, research is explicitly commissioned or legally required in the process of policy formulation. Such research often provides direct guidance for decisions, such as devising new payment methods for Medicare services (Glaser 1989; Hsiao 1989; Ginsburg and Lee 1991; Smith 1992; Oliver 1993); setting up the priority list of services to be covered by the Oregon Health Plan (Eddy 1991; Fox and Leichter 1991; Golenski and Thompson 1991); or developing medical practice guidelines (Gray 1993; Deyo et al. 1997).

Weiss (1977, 1989) finds that research is most commonly used in the policy process as “political ammunition” to support preexisting positions and defined political goals. In the words of a congressional staffer, “Information is used to make a case rather than to help people make up their minds” (Weiss 1989, p. 425). The use of research in this context also strengthens coalitions and may weaken opponents.

In the short term, policy-relevant research is unlikely to cause elected officials or interest group leaders to dramatically change their understanding of an issue and appropriate policy responses. A short-term focus on decision making underestimates the influence of research on policy, however. Evidence suggests that policy change is a product of both lessons learned from past successes and failures as well as gradually changing assumptions and paradigms stemming from research (Caplan 1977; Weiss 1977; Sabatier and Jenkins-Smith 1993). Weiss refers to this as the “enlightenment function” of policy research. Sabatier and Jenkins-Smith acknowledge that policy makers and their allies in an “advocacy coalition” will resist information that goes against their core beliefs and use information that supports those beliefs; but they also find across a number of policy issues that the “cumulative effect of both policy analysis and ordinary learning” can shift the relative power of competing advocacy coalitions and, over time, substantially alter the course of governmental action.

The influence of a new body of research and analysis is likely, therefore, to depend on multiple uses. Weiss (1977, p. 17) concludes,

So social research is used. It is not the kind of use most people have in mind when they hear the word. Not here the imminent decision, the single datum, the weighing of alternative options, and shazam! Officials apparently use social science as a general guide to reinforce their sense of the world and make sense of that part of it that is still unmapped or confusing. A bit of legitimation here, some ammunition for the political wars there, but a hearty dose of conceptual use to clarify the complexities of life.

The analyses by CHBRP of proposed health insurance mandates appear to offer a combination of guidance and political ammunition. On the one hand, they establish what types of consequences are relevant for deliberation and debate and how those consequences might be affected by changes in policy design. On the other hand, they provide specific measures of those consequences for legislators and other interested parties to employ in support of their policy preferences.

What makes some products of research and analysis more useful than others? Weiss and Bucuvalas (1977) cite three key factors: technical competence, implementability, and political acceptability. These factors are not necessarily congruent: the most sophisticated analysis may still produce answers that are politically unacceptable; and successful adoption of a new program does not assure that it will be successfully implemented. At the national level, the studies and policy recommendations of the Physician Payment Review Commission—a group of professional analysts and national health care experts set up to advise Congress—were highly influential in formulating a new payment system for Medicare because they were timely, independent, nonpartisan, and supported by relevant data (Oliver 1993, p. 147). Yet it was only as spending increases on physician services continued to substantially outpace spending on other services, and the adoption of a prospective payment system for hospitals set a political precedent, that Congress adopted the main reform package.

Sorian and Baugh (2002) find that policy makers rate reports on states in the same region or with similar demographics as the most useful. Brevity and clarity are even more important. While most state legislators will read several policy-related articles or reports each week, they strongly prefer short, easy to digest information. Legislative staff, too, prefer short reports or executive summaries, particularly those with bullet points or charts they can use to brief their members. But many also indicate that they need the long versions of studies to, in the words of one staffer, “fully understand the research and verify its accuracy based on my own knowledge” (Sorian and Baugh 2002, p. 267).

Brown (1991, pp. 26–28) argues that the usefulness of health services research depends on the purpose of the study. Because of the limited time and interest policy makers have to absorb sophisticated information on scientific issues, often the simplest function of research—documentation—is more useful than the analysis and prescription that often follow. Research that focuses on documenting the scope or severity of a problem is often more credible as well; once researchers assert cause and effect relationships in their analysis, or shift from analysis to advice by prescribing specific policy options, their work is more likely to be challenged by other experts on the issue.

These findings suggest that CHBRP analysis is likely to be a valued source of information for the small number of legislators and staff members who have leading roles on health insurance issues. The analyses are, by definition, timely and closely related to key legislative decisions; they are developed on a nonpartisan basis; and they focus primarily on supplying technical data and do not make policy recommendations, thus avoiding much potential controversy. The CHBRP would be expected to exert influence because, through its analysis of the medical literature and large datasets, it provides information that is not available elsewhere. That information will be most influential in cases where it identifies or defines a potential impact that was not previously recognized by participants in the policy process.

The influence of CHBRP also depends on its reputation as an independent and reliable source of documentation of medical effectiveness, current patterns of coverage, and the impact of mandates on access to services, public health and, especially, costs. If the underlying models that produce such measures are called into question, then the CHBRP reports will be of less value to policy makers. To prevent problems in this area, the cost analysis team for CHBRP has worked diligently with its chief contractor, Milliman, to explain its sources of data and actuarial methods (UR interview; Kominski et al. 2006). The most obvious threat to academic integrity in the current review process lies not in the 60-day limit for review, but in the restricted analysis of cost impact. The CHBRP currently interprets the provisions of AB 1996 to restrict the estimated cost impact of a proposed bill to the first year of implementation. The program has used this approach as actuarial estimates of premiums are usually based on the following year, and in addition the uncertainty of estimates increases over a longer time frame. As illustrated by the tobacco cessation mandate, services that would produce long-term savings are at an inherent disadvantage using this approach.

VIEWS ON THE VALUE OF CHBRP ANALYSIS FROM GOVERNMENTAL OFFICIALS AND OTHER STAKEHOLDERS

The role that CHBRP has established to date is quite consistent with the use of research in most policy settings.2 The program has a very tight connection to the policy process, because its work is commissioned directly by legislative leaders and is built into legislative routines. Both the narrow construction of CHBRP's mission and the procedural rules adopted by legislators make the reports a central part of policy formulation and political debate. The policy committees in each chamber will not hold hearings on a proposed health insurance mandate until the CHBRP report on the bill is available to members and staff.3

The use of CHBRP research and analysis in the California Legislature—and, for that matter, the state health policy community—is “both extensive and uneven,” the pattern that Whiteman (1987) found in his study of health policy information in Congress. While legislators will periodically read the reports, the primary users are perhaps two dozen specialists inside and outside of state government: (1) the staff who help draft and amend bills on the three policy committees with jurisdiction over health insurance mandates, the Assembly Committee on Health, the Senate Committee on Health, and the Senate Committee on Banking, Finance and Insurance; (2) staff who analyze health legislation for the appropriations committees in the Assembly and Senate, which must approve all bills that will have a fiscal impact on state programs (including health coverage for state employees, Medi-Cal, Healthy Families, and several smaller programs); (3) staff in the two executive agencies that regulate health plans, the Department of Managed Health Care and the Department of Insurance; (4) personal staff for the authors of bills proposing health insurance mandates; (5) the governor's deputy legislative secretary for health issues, who must monitor bills, negotiate with legislators, and recommend that the governor sign or veto individual bills; (6) minority policy and appropriations committee staff for both houses; and (7) lobbyists for health plans, business groups, health care providers, unions, and consumers. A legislative staffer noted that CHBRP reports may eventually come to have additional uses in the courts and among the general public (LS interview).

All the participants interviewed for this study, regardless of their role in the policy process, their partisan affiliation, or general position on health insurance mandates, saw the process of review established by AB 1996 as a positive addition to state policy making. One lobbyist who previously held a legislative staff position argued, “Before [AB 1996], we would have the standard debate: proponents would say it would save more money than it would cost, and we'd say the opposite. The debate has shifted from, ‘Is it beneficial for a child to have a hearing aid?’ to ‘Is it beneficial for the state to require plans to offer benefits that some people might not want?’” (IG interview). While the state's fiscal crisis must also be considered a factor, there was consensus that instituting the health benefits review process has slowed the volume of legislation and improved the quality of proposals in this area. A representative of health plans, which are assessed a fee to cover up to $2 million per year for CHBRP reviews, acknowledged that “We would ask not to pay [the assessment] if we felt it had no impact” (IG interview).

As evidence of this triaging, of the more than one dozen bills that were put on hold while the University of California organized CHBRP, only five were reintroduced in 2004. In 2005, two bills were not introduced early enough to request a CHBRP analysis and were put on hold until the 2006 legislative session (AB 1185, Chiropractic Services and AB 976, Orthotic and Prosthetic Devices for Children). After CHBRP had submitted the first round of nine analyses in March 2005, five bills were not heard in policy committee at the request of the bill author. One was held in policy committee and three were passed out of the legislature and sent to the governor for his signature or veto. An illustration of how CHBRP review can affect the legislative course of action is its analysis of AB 213, which would have required health plans to cover the treatment of lymphedema per specified standards of care and by specified practitioners. The sponsor was instrumental in drafting portions of the legislation and the initial version of the bill referred to standards of care set by three specific organizations. CHBRP analysis indicated, “there is a lack of consensus on the clinical definition of lymphedema, as well as on the standards of care for its treatment, even among the organizations identified in the mandate as defining a current standard of care.” The amended version of AB 213 struck reference to these specific organizations' standards. While other political forces may have contributed to this change in language (and the subsequent hearing cancellation), the sponsor's argument in favor of these standards was not supported by CHBRP analysis.

Among most users, the chief value of CHBRP analysis lies, as suggested by Brown (1991), in “documentation” of existing insurer practices, gaps in access to services, and especially the projected costs of a mandate. The numbers generated by an independent source are eagerly sought by legislative staff and agency officials, in particular, who otherwise often have to rely on data provided by the very industry they are charged with regulating. Staffers quote passages from CHBRP reports verbatim in preparing the legislative analysis for committee members and floor votes; recommendations to the governor from executive agencies and his own staff cite CHBRP findings; and lobbyists attach highlighted sections of CHBRP reports in the letters they send in support or opposition to each bill. The CHBRP estimates appear to have become the common currency for debate over a bill: a lobbyist conceded that they had different figures, but used the CHBRP figures in fighting SB 1555, the maternity benefits bill in 2004 (IG interview). In 2005, CHBRP analyzed two bills that were related to prescription drug coverage—one that would have prohibited the designation of “preferred drugs” within the biological class of drugs for the treatment of rheumatic diseases (SB 913) and the other that would have mandated the drugs from a class of cholinesterase inhibitors as well as other FDA-approved medications for the treatment of Alzheimer's disease. For these technical bills, the CHBRP analyses and testimony provided a common terminology of terms such as “preferred drug,”“formulary,” and “step therapy” during deliberations. This proved valuable in clarifying the author's intent and led to a subsequent amendment of SB 913.

Both representatives of health plans and appropriations analysts believe there are shortcomings in CHBRP reviews. They contend, for example, that the current estimates of cost impact do not provide sufficient information about each of the major segments of the insurance market—large group, small group, individual, and public purchasers—or interaction among those segments (LS interviews; IG interview). A researcher noted that while the sources of data for CHBRP analysis are the best that are available, they can be unreliable in looking at one segment of the market or projecting the impact on different racial and ethnic groups because the response rate for one of the core surveys, the California Health Interview Survey, is only 36 percent (UR interview).

Almost every respondent noted that CHBRP reports, however authoritative, served as “political ammunition” in the manner described by Weiss (1989). A legislative staffer noted that the findings are used to “bolster your argument on either side. The plans use one part, whereas authors use a different part of the same report. That is what you get with any good, balanced report.… It does help inform the discussion, but people will find in the report what they want to find” (LS interview). There is a widespread perception that most users look first and foremost at one measure included in the CHBRP reports, the impact of a proposed expansion of coverage on per member per month insurance premiums in the private insurance market. But several respondents highlighted other indicators as well, including the impacts on access to services and overall insurance coverage.

Overall, staffers believe that inserting CHBRP studies into the policy process has not hurt advocates' arguments for their bills. This may reflect the fact that the structure for CHBRP reports established by AB 1996 usually provides strong political ammunition for both advocates and opponents of mandates. Legislative staff—perhaps the key users of CHBRP analysis—strongly endorse the broad scope of analysis required by AB 1996. The assessment of medical effectiveness and public health impact are important, they argue, for maintaining a systemwide perspective instead of focusing on short-term financial costs only. Even with the primary focus on costs, one staffer argued, “The point of economic analysis was to demonstrate that things didn't cost so much.” Another staffer agreed, commenting that the purpose of AB 1996 was not to help insurance companies kill all mandate bills (LS interviews). In its initial round of reviews in 2004, the CHBRP fulfilled legislative requests to review 13 bills. In 2005, the CHBRP conducted another 12 reviews, including 10 bills and two amendments. While many of the mandates proposed in 2004 focused on preventive services, the 2005 bills focused primarily on specific treatments for diseases such as rheumatism, autism, Alzheimer's, and breast cancer. In addition, legislators proposed two broad-based mandates—an expansion of the California mental health parity law and a mandate to cover chiropractic services. All of the proposed mandates were introduced by Democrats.

In terms of influencing legislators' voting decisions, many participants believe that CHBRP studies have had relatively little impact. The trade associations representing health plans have a strict policy of opposing every mandate bill, no matter how small the cost or how large the public health impact (IG interviews). On occasion, because of the nature of the issue, the evidence of impact, or conflicting positions among their own members, the associations may remain neutral on a mandate bill. Unless that happens, voting will closely follow party lines with Democrats voting yes and Republicans voting no (GS interview; LS interviews). A focus on this pattern of partisanship in final votes, however, masks what appears to be a relatively powerful bipartisan response to CHBRP not only in the number of mandate bills introduced but also in the refinement of proposals in reaction to CHBRP estimates of impact and the debates that are triggered around those estimates.

Participants cited several moments in the 2004 legislative session when CHBRP analysis influenced the policy process. The report on SB 1158 found that hearing aids for children are medically valuable, but it also found that there was very little problem of access. Because public health insurance programs already covered hearing aids and because middle-income families could afford the periodic costs, it seemed that this was not a high priority relative to other mandates (LS interview; AA interview). SB 1158 passed both houses of the legislature but Governor Schwarzenegger vetoed it, arguing that it would have little public health impact and that even a low-cost mandate would make insurance coverage less affordable (GS interview; Schwarzenegger 2004).

According to a legislative staffer, health plans strongly opposed AB 2185, the bill on childhood asthma management introduced by Dario Frommer (D), the Assembly majority leader and former chair of the Assembly Committee on Health: “There was nothing they were going to do on that bill. After the [CHBRP] report came out, they began negotiating with the author … talking about what they could live with” (LS interview). Among its findings, the CHBRP analysis estimated that asthma management would result in up to 17,800 fewer missed school days per month, and eliminate more than one-quarter of all asthma-related emergency room visits and hospitalizations for children. In exchange for health plans dropping their opposition to the bill, Frommer amended AB 2185 to scale back coverage to include asthma-related equipment but not a fuller range of outpatient education and self-management services (Halpin et al. 2006; LS interviews).

Many participants argued that the CHBRP analysis was a significant factor in killing SB 1192, a bill to mandate coverage of a wide range of substance-use disorders, including tobacco and alcohol addiction (CHBRP 2004d, e). Before 2004, the bill had been introduced in several versions by Senator Wesley Chesbro (D), chair of the Senate Budget Committee. A legislative staffer noted that several external factors created difficulties for the bill; the main ones were a highly contentious fight over workers' compensation reform, which meant that legislators were very reluctant to pass legislation that would add significantly to employers' health care costs; and a massive state budget deficit, which would grow by tens of millions of dollars as the CalPERS benefits for state employees did not have very generous coverage for addiction treatment. But the estimate of total costs in the CHBRP analysis was the “nail in the coffin” for SB 1192, even though many advocates argued that the estimate ignored long-term savings and public health improvements associated with smoking cessation and other interventions for substance abuse (LS interviews; AA interview; UR interview; IG interview). The bill passed the Senate but died in the Assembly—an unexpected event for some observers given that, once Arnold Schwarzenegger replaced Gray Davis, the incentives for Democratic legislators were to “roll everything down to the Republican governor and make him take the heat for vetoing popular bills” (IG interview).

In 2005, the CHBRP analysis of SB 576 on tobacco cessation was used extensively and the program was asked to review two amendments that changed cost sharing requirements for prescription drugs, counseling, and over-the-counter medications. Legislative staff, staff from the Department of Managed Health Care, and the Governor's Office stated that components of the CHBRP review, including estimated take-up rates for the benefit, projected quit rates, public health impact, and impact on premiums, were part of deliberations in both the legislature and the governor's office. In the end, the bill made it out of the appropriations committees and both houses but was vetoed. The Governor's veto message for SB 576 specifically cited CHBRP's utilization estimates relative to the cost estimates. It also highlighted his general philosophy of opposition to insurance mandates, stating:

This bill reflects a difficult policy choice: focus on providing access to affordable health insurance products that an average Californian can purchase or impose a mandate that every person or employer that pays for health insurance pays a higher premium to cover costs for a universally offered tobacco cessation benefit. Mandating coverage is not the appropriate approach to take at this time. I believe we should build upon California's anti-smoking success and encourage plans to get more smokers to utilize existing tobacco cessation benefits and persuade additional plans to include tobacco cessation benefits on a voluntary basis [http://www.governor.ca.gov/govsite/pdf/vetoes_2005/SB_576_veto.pdf].

CHALLENGES IN IMPROVING THE CONNECTION BETWEEN RESEARCH AND POLICY

Officials in the University of California Division of Health Affairs, as well as the professional staff at CHBRP and its participating faculty, have gone to great lengths to establish a credible, independent review of proposed health insurance mandates. The legislative staff and other users of CHBRP research and analysis find the reports on pending health insurance mandate bills to be informative and routinely incorporate the findings into their analytic and political activities. In sum, essentially all participants in the state health policy community believe that the health benefits review process initiated by AB 1996 makes a constructive contribution to policy formulation and debate. Nonetheless, they identify a number of challenges for CHBRP as it continues to refine its organizational capacity, methods of review, and communications with policy makers and other stakeholders in health insurance mandates.

First, the CHBRP must consider whether it should do its work in what one trade group representative called an “ivory tower” process, or whether it should invite feedback from stakeholder groups during the review process. The representative argued that industry experts could help identify potential pitfalls as a study gets underway; and that the CHBRP should solicit comments on its reports before they are made public (IG interview). By making the process more open and interactive, it might be possible to create more dialogue between the sponsors of mandate bills and an industry that instructs its lobbyists to oppose all such proposals. A more participatory process could diminish the perceived independence and objectivity of the current process and its products, however.

Second, many inside and outside of the process in Sacramento will question why the highest cost mandates are the first to fall. Some perceive that the immediate financial impact of a mandate is given priority over prevention and the long-term public health impact. The CHBRP methodology appears to reinforce this bias by confining its estimates of cost impact to the initial year of a proposed mandate. As noted earlier, services like tobacco cessation will have a far more favorable benefit–cost ratio as the time frame for analysis is stretched out. For these reasons, the CHBRP is re-examining its cost impact methods to determine whether long-term impacts can be estimated when appropriate data and simulation models are available. Short-term costs also weigh heavily in the appropriations process. In California, health care legislation with a fiscal impact on state programs must be approved by both the policy committee and the appropriations committee in each house. If the fiscal impact on the state budget is greater than $150,000—“barely a sneeze in health care,” as one staffer noted—the chair of the appropriations committee holds it in a “suspense file” until the end of the legislative session, when the state budget is ordinarily decided and the appropriators can see how much room there is for new spending. Then all the bills are reviewed and, in consultation with party leaders, the chair announces which bills will receive consideration and thus an opportunity to move to a floor vote. The bills with high price tags are at a disadvantage in this stage of the legislative process (LS interview). Establishing a longer time frame for modeling the benefits and costs of a proposed mandate would strengthen CHBRP reports as a source of “guidance” in policy development.

Third, the CHBRP will likely need to adopt a consistent policy on revising its analyses in response to inquiries by authors or legislative amendments. Even though AB 1996 restricts the review by CHBRP to the original language of the bill as it was introduced, there is an unavoidable desire by policy makers and other stakeholders for revised estimates as bills are amended and sometimes dramatically altered in their scope and purpose. Each bill presents a “moving target” for analysts and it is probably impractical to substantially alter a study in the initial 60-day study period. But if a bill is amended in order to gain committee approval and then moves to the other house or onto the governor to be signed or vetoed, a number of participants in the latter stages of the process may look to CHBRP to offer new cost and coverage estimates. In 2004, the CHBRP responded to direct requests for additional analyses from Senator Chesbro as he made major modifications to SB 101 and SB 1192, his bills to mandate for parity in coverage of substance abuse services. In 2005, CHBRP conducted two revised analyses on amendments to the tobacco cessation bill proposed by Senator Deborah Ortiz, chair of the Senate Committee on Health. The amendments were relatively narrow in scope and only altered the copayment requirements. On the other hand, CHBRP did not conduct an analysis of the amendment proposed by Senator S. Joseph Simitian to prohibit plans from using “step therapy” for biological medications for the treatment of rheumatic diseases, as the amendment was complex and would impact every aspect of the CHBRP report—the medical effectiveness, cost and public health impact analysis. In addition, it was not feasible to conduct the analysis in time for the relevant hearing. The issue at this point is whether legislators and staff will now expect the CHBRP to review amended bills on an expedited basis and whether the program staff and academic researchers are prepared and equipped to engage in a more iterative process on multiple bills in the same legislative session. Several participants inside and outside the legislature must prepare analyses of hundreds of bills in a few weeks' time each year, and they believe it should not be difficult for the CHBRP to turn around a handful of revised analyses on mandate bills on which it has already done the basic groundwork. The risk is that professional responsiveness on the part of CHBRP might be viewed as currying of political favor by some of those with stakes in the legislative outcome.

Fourth, the CHBRP must maintain interest among its university-based researchers for participating in a demanding, but increasingly routine, process of review. Setting up the methods for review and strengthening teamwork among the academic institutions has been a rewarding experience, but whether faculty will want to continue in their role indefinitely is still in question. Because CHBRP reviews the exact provisions of bills as they are introduced, there is little opportunity to smooth out the workload throughout the year. A rush of bills arrives in January or February and then the research teams must conclude their work on all of them within 60 days, including the review by national advisory council members and revisions by CHBRP staff. There is also bound to be significant variation in the workload from year to year, depending on the state fiscal picture, elections, and other factors. So it may be hard to ensure there are a sufficient number of expert analysts who, on the one hand, can drop everything when the legislature requests a CHBRP study but, on the other hand, can be usefully employed in other research projects when the CHBRP workload drops.

Finally, once a new government program is successfully established, policy makers are tempted to “pile on” new responsibilities over time (Bardach 1977). AB 1996 gives the CHBRP a very restricted task but its basic function could easily be expanded to other issues in health insurance coverage. It could conduct retrospective reviews of the medical effectiveness, cost impact, and public health implications of the numerous mandates that were enacted before AB 1996. If the legislature were to propose repealing existing mandates, the CHBRP could be asked to review the impact of those changes on the health care market. Some researchers are currently trying to establish a review process for optional Medi-Cal benefits, and the CHBRP would presumably be the most likely organization to conduct those studies (UR interview). There is also a hint of a major initiative from the California Department of Insurance to stop what it calls socially irresponsible “venue shopping” by insurers who want to use different benefit packages in the state to their financial advantage. The insurance commissioner would like to establish equivalent benefits for all plans offering employer-sponsored insurance, whether they are regulated by the Department of Insurance or the Department of Managed Health Care (LS interview; AA interview; IG interview). This might thrust the CHBRP into a dramatically different role of determining which benefits must be added or dropped in each segment of the market to achieve uniformity. If such an initiative comes to pass, it will be a major technical, political, and organizational challenge for the University of California and its newly established health benefits review program.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank the many individuals who participated in interviews outlining their perspective on the development of the California Health Benefits Review Program and their experience with the program. We also wish to thank Susan Philip of the California Health Benefits Review Program for providing data on benefits review programs in other states and other helpful background information. Finally, we would like to acknowledge the detailed and valuable comments and suggestions of an anonymous reviewer.

NOTES

In some states, the law is not yet implemented and in others it is not actively used to evaluation proposed health insurance mandates.

This section draws upon findings from a series of 16 personal interviews with 20 key informants, all of whom either help produce or use CHBRP research and analysis on health insurance mandates. The interviews were conducted in person or by phone by the principal investigator in October and November 2004.

The rule-making CHBRP review a prerequisite for committee consideration is not prescribed in AB 1996 and is subject to the prerogative of the committee chairs.

PERSONAL INTERVIEWS

Code for references to interviews:

LS legislative staff

GS governor's staff

IG interest group

AA administrative agency staff

UCOP University of California Office of the President (including CHBRP staff)

UR university researcher

Bain, Scott. Interview with principal consultant, Assembly Appropriations Committee, Sacramento, California, 19 October 2004.

Capell, Beth. Phone interview with principal, Capell and Associates, 28 October 2004.

Cate, George. Interview with consultant, Senate Appropriations Committee, California Legislature, Sacramento, California, 21 October 2004.

Eowan, Ann. Interview with vice president for government affairs, Association of California Life and Health Insurance Companies, Sacramento, California, 20 October 2004.

Figueroa, Richard and Brian Bugsch. Interview with analysts, strategic planning and policy, California Department of Insurance. Sacramento, California, 21 October 2004.

Fitzgerald, Jennifer. Phone interview with deputy legislative secretary, office of Governor Arnold Schwarzenegger, 28 October 2004.

Gluck, Michael. Phone interview with executive director, California Health Benefits Review Program, 18 October 2004.