Abstract

The glycosylation of serine and threonine residues with a single GlcNAc moiety is a dynamic posttranslational modification of many nuclear and cytoplasmic proteins. We describe a chemical strategy directed toward identifying O-GlcNAc-modified proteins from living cells or proteins modified in vitro. We demonstrate, in vitro, that each enzyme in the hexosamine salvage pathway, and the enzymes that affect this dynamic modification (UDP-GlcNAc:polypeptidtyltransferase and O-GlcNAcase), tolerate analogues of their natural substrates in which the N-acyl side chain has been modified to bear a bio-orthogonal azide moiety. Accordingly, treatment of cells with N-azidoacetylglucosamine results in the metabolic incorporation of the azido sugar into nuclear and cytoplasmic proteins. These O-azidoacetylglucosamine-modified proteins can be covalently derivatized with various biochemical probes at the site of protein glycosylation by using the Staudinger ligation. The approach was validated by metabolic labeling of nuclear pore protein p62, which is known to be posttranslationally modified with O-GlcNAc. This strategy will prove useful for both the identification of O-GlcNAc-modified proteins and the elucidation of the specific residues that bear this saccharide.

The glycosylation of nuclear and cytoplasmic proteins at serine and threonine residues by the addition of a single GlcNAc residue (O-GlcNAc) is a widespread posttranslational modification (1–4). This modification has been found on numerous proteins including, for example, transcription factors (5), nuclear pore proteins (6–8), and enzymes (9). The enzyme catalyzing the O-GlcNAc modification of cellular proteins, UDP-GlcNAc:polypeptidyltransferase (OGTase), is essential for cell viability in mammals (10) and is conserved in a range of organisms from Arabidopsis thaliana (11) to humans (12–14). Some proteins have been found to bear the O-GlcNAc modification at sites that are otherwise phosphorylated, suggesting a possible role in cellular signaling (15, 16). Isoforms of the enzymes involved in O-GlcNAc metabolism have been found in the nucleus, cytoplasm, and mitochondria (17–19).

There is recent evidence that dysregulation of cellular O-GlcNAc levels is involved in the etiology of type II diabetes. Indeed, increased cellular O-GlcNAc levels correlate with decreased insulin-mediated glucose uptake in cells and in vivo (9, 20, 21). This observation is consistent with a role for increased flux through the hexosamine biosynthetic pathway in “sensing” increased levels of exogenous glucose (22). The end product of this pathway, the nucleotide sugar donor UDP-GlcNAc (5a, Fig. 1A), is a substrate for OGTase. Indeed, a direct link between increased levels of exogenously supplied glucose and elevated levels of cellular O-GlcNAc-modified proteins has been demonstrated in an animal model of diabetes (23), 3T3-L1 adipocytes (21), and diabetic patients (24).

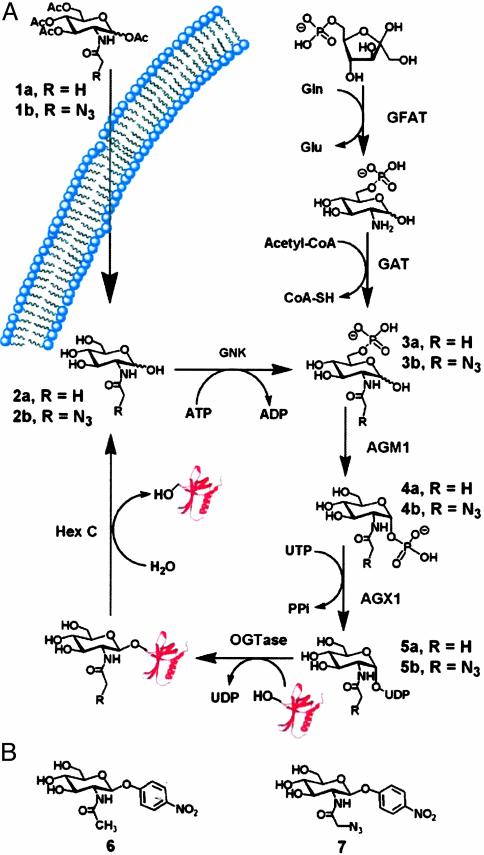

Fig. 1.

(A) The de novo hexosamine biosynthetic pathway, salvage pathway, and dynamic glycosylation of nucleocytoplasmic proteins. O-GlcNAc-modified proteins are biosynthesized in a series of enzymatic steps. The first committed step in the de novo process is the conversion of fructose-6-phosphate to glucosamine-6-phosphate through the action of the enzyme glutamine:fructose-6-phosphate amidotransferase (GFAT). Glucosamine-6-phosphate is then converted to the common intermediate N-acetylglucosamine-6-phosphate (3a) through the action of acetyl-CoA:d-glucosamine-6-phosphate N-acetyltransferase (GAT). The salvage pathway bypasses the de novo pathway through the action of GlcNAc kinase (GNK) and also generates GlcNAc-6-phosphate (3a). This intermediate is converted to GlcNAc-1-phosphate (4a) through the action of AGM1. N-acetylglucosamine-1-phosphate is converted to the end product of the hexosamine biosynthetic pathway, UDP-GlcNAc (5a), through the action of UDP-GlcNAc pyrophosphorylase (AGX1). OGTase transfers the saccharide moiety of UDP-GlcNAc to protein substrates within the cell. Hexosaminidase C (O-GlcNAcase) acts to cleave the glycosidic linkage of posttranslationally modified proteins to liberate the protein and GlcNAc (2a). Exogenously added Ac4GlcNAz (1b) diffuses into the cell and is deacylated through the action of intracellular esterases, and then enters into the salvage pathway. (B) Chromogenic substrates for O-GlcNAcase. Shown are para-nitrophenyl 2-acetamido-2-deoxy-β-d-glucopyranoside (6) and para-nitrophenyl 2-azidoacetamido-2-deoxy-β-d-glucopyranoside (7).

Despite numerous studies implicating the O-GlcNAc modification of proteins as a modulator of cellular processes, the molecular details of the modification, including the complete repertoire of O-GlcNAc-modified proteins and the specific sites of modification, remain predominantly unknown. Indeed, although many proteins appear to be O-GlcNAc modified (2) relatively few have been identified and fewer still have had the specific glycosylated residues identified (25). Furthermore, no consensus sequence directing the O-GlcNAc modification of proteins has been established on the basis of known modification sites. With the goal of answering these questions, we developed a method for probing the O-GlcNAc modification that exploits its biosynthetic origin as reported herein.

Boehmelt et al. (26) have demonstrated that disruption of the gene encoding glucosamine-6-phosphate acetyltransferase, which disrupts the de novo hexosamine biosynthetic pathway, is lethal in mice. Exogenous GlcNAc, however, can compensate for this otherwise deleterious gene knockout in cultured fibroblasts (26). Thus, GlcNAc can be reintroduced by a salvage pathway initiated by the action of GlcNAc kinase (Fig. 1 A). The possibility exists, therefore, of exploiting the promiscuity of the enzymes involved in this hexosamine salvage pathway to deliver abiotic moieties appended to the N-acyl group of GlcNAc (2a, Fig. 1A) to sites of O-GlcNAc modification. Precedent for exploiting the flexibility of carbohydrate biosynthetic pathways has been established in studies on the sialic acid biosynthetic pathway (27–29). For example, treatment of cultured cells with 2-azidoacetylmannosamine (ManNAz), an analog of the sialic acid precursor N-acetylmannosamine, resulted in biosynthesis of the corresponding azido sialic acid and its incorporation into cell surface glycoproteins. The azido groups could be detected on the cell surface with phosphine reagents by using a recently developed chemoselective reaction known as the Staudinger ligation (Fig. 2) (30). The azide moiety is a bio-orthogonal chemical handle that can be selectively conjugated to exogenous probes in this fashion, without interference from other cellular components.

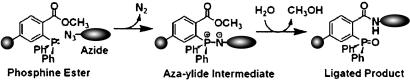

Fig. 2.

The Staudinger ligation. An alkyl azide moiety appended to a molecule of interest can be covalently derivatized with a triarylphosphine ester conjugated to a variety of probes. The reaction proceeds via an aza-ylide intermediate, which undergoes rearrangement to yield the final product.

Our aim was to examine the promiscuity of the hexosamine biosynthetic pathway to evaluate and exploit its potential to deliver azides to O-GlcNAc-modified proteins. The delivery of such bio-orthogonal functional groups to sites of O-GlcNAc modification could greatly facilitate the identification of the glycosylated residues. A strategy that permits the simultaneous identification of O-GlcNAc-modified proteins and the specific sites of modification would be a powerful tool for elucidating the functional significance of O-GlcNAc. Here we demonstrate that N-azidoacetylglucosamine (1b, GlcNAz, Fig. 1 A) can be processed by the hexosamine salvage enzymes and incorporated in living cells. The azide moiety provides a unique chemical handle for proteomics analysis of O-GlcNAc-modified proteins from cells.

Methods and Materials

Chemical Synthesis. Details describing the synthesis of compounds 1b–5b and 7 can be found in Supporting Materials and Methods and Schemes 1–4, which are published as supporting information on the PNAS web site, www.pnas.org.

Cloning of Phosho-N-Acetylglucosamine Mutase (AGM1), Expression, Purification, and Enzymatic Assay of Recombinant Enzymes. Details describing the subcloning of AGM1 and expression of recombinant proteins and enzyme assays can be found in Supporting Materials and Methods.

Western Blotting. SDS/PAGE loading buffer was added to each sample, and after heating at 96°C aliquots were loaded onto precast 10% or 12% Tris·HCl polyacrylamide gels (Bio-Rad). After electrophoresis, the samples were electroblotted to nitrocellulose membrane (0.45 μm, Bio-Rad). The membrane was blocked by using 5% BSA (fraction V, Sigma) in PBS (blocking buffer A for samples reacted with biotin-phosphine 8, see Fig. 4A) or 5% low-fat dry powdered milk [blocking buffer B for samples reacted with FLAG-phosphine 9 (see Fig. 4A) (30)], pH 7.0, containing 0.1% Tween 20. Membranes were then incubated with a solution of blocking buffer A containing streptavidin-horseradish peroxidase (HRP) conjugate or blocking buffer B containing anti-FLAG-HRP conjugate. Membranes were washed, and detection of membrane-bound streptavidin-HRP or anti-FLAG-HRP conjugates was accomplished by chemiluminescence. For detection of nuclear pore protein p62, the membrane was incubated with mAb 414 in blocking buffer B, washed, and incubated with a secondary goat anti-mouse-HRP conjugate in blocking buffer B. The membrane was washed again, and detection of membrane-bound donkey anti-mouse-HRP conjugate was accomplished as for anti-FLAG-HRP. Control samples were treated in the same manner except that specific reagents were replaced by buffer where appropriate.

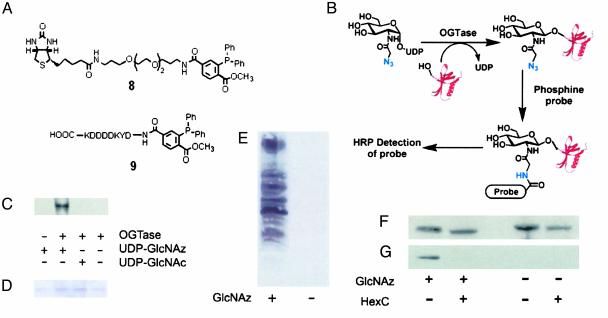

Fig. 4.

UDP-GlcNAz is a substrate for OGTase both in vitro and in living cells. (A) Phosphine probes used in this study. Compound 8, biotin-phosphine; compound 9, FLAG-phosphine. (B) Schematic showing the labeling approach and Staudinger ligation to install the desired probe. The modification of proteins may be carried out either in vitro using recombinant OGTase or through metabolic processes within cultured cells. Chemoselective ligation of the glycosylated protein results in the attachment of a probe at the site of glycosylation that is detected by using a probe-specific HRP-antibody conjugate. (C) Western blot showing the in vitro enzymatic glycosylation of nuclear pore protein p62 using OGTase and UDP-GlcNAz. After enzymatic reaction the samples were labeled with phosphine 8 and then analyzed by Western blot using streptavidin-HRP. (D) SDS/PAGE gel of the same reactions as in C stained with Coomassie blue. (E) Western blot of purified nuclear extracts obtained from Jurkat cells cultured in the presence or absence of Ac4GlcNAz after reaction with FLAG-phosphine. The blot was probed with mouse anti-FLAG-HRP conjugate. (F) Western blot of p62 immunoprecipitated from Jurkat cells cultured in the presence or absence of Ac4GlcNAz with mouse anti-p62 antibody (mAb 414). Samples either were digested overnight with O-GlcNAcase before the ligation reaction or were untreated. The blot is the same as shown in G and was reprobed, after being stripped, using mAb 414 followed by donkey anti-mouse-HRP antibody conjugate. (G) Western blot of p62 immunoprecipitated from Jurkat cells cultured in the presence or absence of Ac4GlcNAz and digested overnight with O-GlcNAcase before the ligation reaction or untreated. All samples were subsequently reacted with FLAG-phosphine. The blot was probed by using the anti-FLAG-HRP conjugate.

Activity of OGTase with UDP-GlcNAz Analyzed by Western Blot. An aliquot of partially purified recombinant OGTase was combined with recombinant nuclear pore protein p62 in the presence of UDP-GlcNAz or UDP-GlcNAc in Tris, pH 7.5 containing 12.5 mM MgCl2, and 1 mM 2-mercaptoethanol and incubated overnight at room temperature. The reaction mixture was diluted 2-fold by the addition of the biotin-phosphine probe (8, see Fig. 4A) in a solution of 20% dimethylformamide in distilled H2O (1 mM final concentration) and incubated at 37°C for 1.5–2 h. Samples were analyzed by Western blot as described above.

Culturing of Jurkat Cells and Metabolic Labeling Conditions. Jurkat cells were cultured in RPMI medium 1640 supplemented with 5–10% FBS. Aliquots of Ac4GlcNAz (1b) in ethanol were delivered into 200-ml culture flasks, the ethanol was evaporated, and the flasks were stored at 4°C. Culture flasks containing Ac4GlcNAz were seeded with Jurkat cells at a density of 2.5 × 105 cells per ml in 50 ml of culture medium, to yield a final concentration of Ac4GlcNAz of 40 μM. The cells were incubated at 37°C for 2–3 days at which time their density was 1.0 × 106 cells per ml. Control cultures without Ac4GlcNAz were treated in the same manner.

Isolation of Nuclei from Jurkat Cells and Chemical Labeling of Nuclear Proteins. Nuclei were isolated from Jurkat cells by Douce homogenization of hypotonic swollen cells and differential centrifugation through a sucrose gradient. Samples were treated with protein denaturing conditions and sonicated. Centrifugation of the samples yielded a supernatant that was used as a sample of nuclear proteins. Nuclear proteins were incubated with the FLAG-phosphine probe (9, see Fig. 4A, 0.5 mM stock solution in PBS) at a final concentration of 0.25 mM probe for6hat37°C.

Immunoprecipitation of p62 and Analysis by Western Blot. Jurkat cells were cultured as described above. Cells were harvested and pooled by centrifugation, washed, and pelleted. Cold lysis buffer was added (50 mM Tris, pH 7.4/100 mM NaCl/2 mM EDTA/1 mM PMSF/1% SDS), and the mixture was heated at 96°C for 5 min after which the cells were sonicated. A cold nonionic detergent solution was added (50 mM Tris, pH 7.4/100 mM NaCl/2 mM EDTA/1 mM PMSF/1.66% Triton X-100/3.3% BSA) to yield a final SDS concentration of 0.4%. The solution was mixed and centrifuged, after which mAb 414 bound to protein G-Sepharose was added to the supernatant. The mixture was gently rocked for 2 h after which the protein G beads were pelleted by centrifugation and washed extensively. The buffer was removed, and aliquots of the immunoprecipitated p62 from cells cultured with Ac4GlcNAz and the control culture were treated with O-GlcNAcase overnight at 37°C. Samples were analyzed for the presence of the azide and for p62 by Western blot as described above.

See Supporting Materials and Methods for details.

Results and Discussion

GlcNAz Is Efficiently Processed by the Hexosamine Biosynthetic Pathway in Vitro. Recent work in our laboratory suggests that GlcNAz (Fig. 1A, 2b), unlike 2-azidoacetylmannosamine (ManNAz), is essentially excluded from cell surface glycoproteins when cultured with human cells (31). The only observed entry into membrane glycoproteins occurs via inefficient conversion of GlcNAz to ManNAz followed by further conversion to N-azidoncetyl sialic acid (31, 32). One possible explanation for the absence of GlcNAz in membrane glycoproteins of GlcNAz-treated cells is inefficient conversion of this sugar to UDP-GlcNAz (Fig. 1A, 5b) via the GlcNAc salvage pathway (Fig. 1 A). To address this question directly, we investigated the in vitro specificity of each enzyme involved in the GlcNAc salvage pathway. A relatively high tolerance of these enzymes for the appended N-azidoacetyl group would be a prerequisite for the goal of delivering GlcNAz to O-GlcNAc-modified proteins.

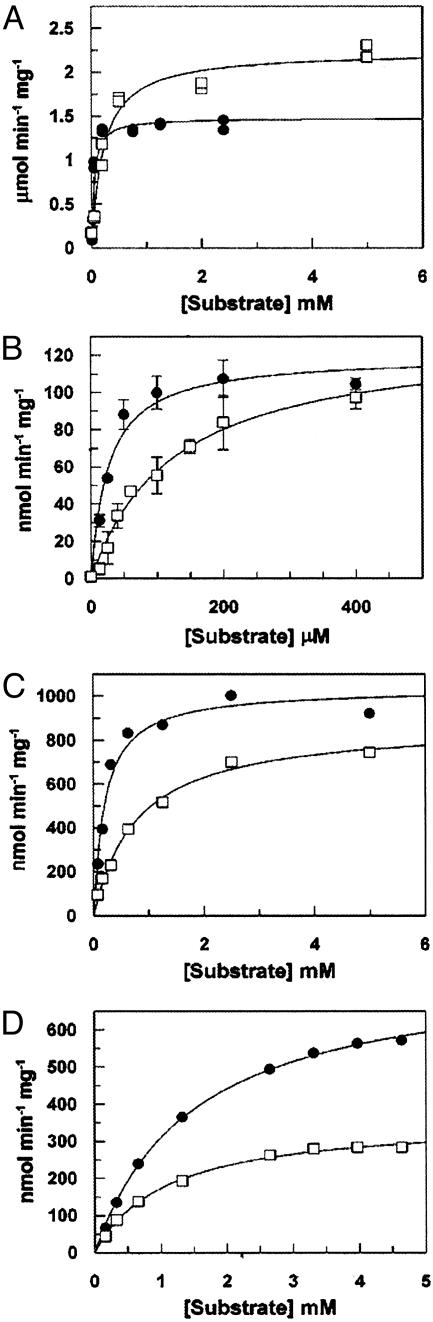

To this end, the 2-N-azidoacetyl derivative of each intermediate in the GlcNAc salvage pathway was chemically synthesized and evaluated with each enzyme leading to the formation of UDP-GlcNAc (Fig. 1A, 5a) from GlcNAc (Fig. 1A, 2a). As shown in Fig. 3 A–C, GlcNAc kinase (33), AGM1 (34), and UDP-GlcNAc-pyrophosphorylase (35) act with similar efficiency on both the natural substrates (Fig. 1 A, 2a–4a) and unnatural azido-substituted analogues (Fig. 1 A, 2b–4b). The kinetic parameters of each substrate are shown in Table 1. The greatest decrease in catalytic efficiency was observed with UDP-GlcNAc pyrophosphorylase, where the azido derivative was converted to the natural substrate with a 4-fold decrease in the value of the apparent second-order rate constant, but with only a 13% decrease in the value of Vmax. Indeed, the value of Vmax for each enzyme in the salvage pathway was relatively unaffected by the pendant azide moiety. The effect on the relative apparent second-order rate constant stems from increases in the value of Km for substrates bearing the N-azidoacetyl group. From these studies it appears that the biosynthesis of UDP-GlcNAz should not be a major barrier for the incorporation of GlcNAz into glycoproteins. Furthermore, owing to the relatively competitive efficiency of these enzymes with their unnatural azido substrates, the GlcNAc salvage pathway may be capable of supporting the biosynthesis of a cytosolic pool of UDP-GlcNAz (Fig. 1, 5b) that could compete with the relatively abundant endogenous levels of UDP-GlcNAc (Fig. 1A, 5a) as a substrate for OGTase.

Fig. 3.

Substrate specificity of the enzymes in the GlcNAc salvage pathway and O-GlcNAcase. (A) N-acetylglucosamine kinase. (B) AGM1. (C) UDP-GlcNAc pyrophosphorylase. (D) O-GlcNAcase. Each enzyme was incubated with the appropriate natural substrate (•) or corresponding azido substrate analogue (□) and assayed as described in Supporting Materials and Methods. Error bars (SD of three replicates) are shown only for the kinetic evaluation of AGM1 as random errors in the assay were significant compared with the assays of the other enzymes.

Table 1. Kinetic constants for the enzymes in the GlcNAc salvage pathway and O-GlcNAcase.

| Enzyme | Substrate | KM, μM | Vmax/[E]T, μmol·min-1·mg-1 | Vmax/KM [E]T, μmol·μM-1·mg-1·min-1 |  |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| GNK | GlcNAc | 50 ± 10 | 1.5 ± 0.1 | 30 × 10-3 | ||

| GlcNAz | 210 ± 40 | 2.2 ± 0.1 | 10 × 10-3 | 1.50 | 0.33 | |

| AGM1 | GlcNAc-6-P | 30 ± 10 | 0.12 ± 0.01 | 4.0 × 10-3 | ||

| GlcNAz-6-P | 120 ± 20 | 0.13 ± 0.01 | 1.1 × 10-3 | 1.08 | 0.28 | |

| AGX1 | GlcNAc-1-P | 200 ± 50 | 1.00 ± 0.05 | 5.0 × 10-3 | ||

| GlcNAz-1-P | 700 ± 90 | 0.90 ± 0.03 | 1.3 × 10-3 | 0.90 | 0.26 | |

| HexC | pNPGlcNAc | 1,500 ± 100 | 0.77 ± 0.01 | 0.51 × 10-3 | ||

| pNPGlcNAz | 1,100 ± 100 | 0.36 ± 0.01 | 0.33 × 10-3 | 0.47 | 0.65 |

Interestingly, it is known that UDP-GlcNAc, and quite possibly UDP-GlcNAz, is a powerful inhibitor of glutamine:fructose-6-phosphate amidotransferase, the rate-determining enzyme in the de novo hexosamine biosynthetic pathway (36). Because the salvage pathway remains unaffected by such feedback inhibition, UDP-GlcNAz levels will increase even as potent feedback inhibition blocks the de novo biosynthesis of UDP-GlcNAc. The net result is that the ratio of UDP-GlcNAz to UDP-GlcNAc should steadily increase over time such that significant levels of UDP-GlcNAz accumulate within the cell. Three possible explanations for the apparent low-efficiency incorporation of GlcNAz into cell surface glycoproteins, therefore, are: (i) UDP-GlcNAz is not efficiently transported into the lumen of organelles of the secretory pathway, (ii) UDP-GlcNAz is diverted into other nuclear and cytosolic pathways such as the modification of proteins with O-GlcNAz, or (iii) Golgi GlcNAc transferases do not tolerate the azide modification.

UDP-GlcNAz Is a Substrate for UDP-GlcNAc:Polypeptidyltransferase. The realization that UDP-GlcNAz may be generated from GlcNAz within cells, and could accumulate to levels competitive with UDP-GlcNAc, prompted us to investigate the ability of OGTase to catalyze the transfer of GlcNAz from UDP-GlcNAz to target proteins in vitro. To this end, UDP-GlcNAz was chemically synthesized and tested as a substrate for recombinant OGTase, using recombinant nuclear pore protein p62 (a known acceptor substrate for OGTase) (37) as an acceptor. p62 was treated with UDP-GlcNAz in the presence of OGTase, and then reacted with biotin-phosphine 8 (Fig. 4 A and B). SDS/PAGE of the resulting samples followed by electroblotting to nitrocellulose and chemiluminescent detection using streptavidin-HRP revealed specific labeling of p62 (Fig. 4C). The labeling depended on the presence of both UDP-GlcNAz and OGTase. Although the efficiency of transfer cannot be evaluated with this assay, it is clear that OGTase is capable of supporting transfer of GlcNAz from UDP-GlcNAz to known protein substrates. We envision that such in vitro modification of target proteins using recombinant OGTase and UDP-GlcNAz, in tandem with phosphine labeling, will provide a rapid means for the identification of sites of O-GlcNAc modification on purified recombinant proteins.

GlcNAz Is a Substrate for O-GlcNAcase. The posttranslational modification of proteins with GlcNAc is a dynamic process dictated by the addition of GlcNAc through the action of OGTase and removal of this residue by the enzyme hexosaminidase C (O-GlcNAcase) (17). Consequently, we were interested in the efficiency of the O-GlcNAcase-catalyzed cleavage of the glycosidic linkage of GlcNAz glycosides relative to substrates bearing the natural 2-acetamido group. Wells et al. (38) have shown that para-nitrophenyl 2-acetamido-2-deoxy-β-d-glucopyranoside (pNP-GlcNAc, 6, Fig. 1B) is a substrate for O-GlcNAcase, which provides a convenient means to monitor enzyme activity spectrophotometrically. We therefore prepared para-nitrophenyl 2-azidoacetamido-2-deoxy-β-d-glucopyranoside (7, Fig. 1B) as an analogue of pNP-GlcNAc so that the effect of the azide functionality on the catalytic efficiency of O-GlcNAcase could be established. As shown in Table 1 and Fig. 3D, O-GlcNAcase tolerates the azido group remarkably well, with only a 35% decrease in the value of the apparent second-order rate constant and a 2-fold decrease in the value of Vmax relative to the native substrate. Collectively, these results, and the tolerance of the GlcNAc salvage pathway toward the azide moiety, suggest that GlcNAc can be substituted by GlcNAz in O-GlcNAc-modified proteins within living cells. Furthermore, the activity of O-GlcNAcase on GlcNAz-bearing substrates suggests that the dynamic nature of the O-GlcNAc modification may not be grossly altered in the presence of GlcNAz.

Incorporation of GlcNAz into Nuclear Proteins in Cultured Human Cells. The above in vitro data prompted us to investigate the incorporation of GlcNAz into proteins within cultured human cells. Jurkat cells are known to express proteins modified with O-GlcNAc at clearly detectable levels (39) and thus served as a good model system for experiments with GlcNAz. For cell feeding experiments we used the peracetylated form of GlcNAz (Ac4GlcNAz), as it has superior cell membrane penetration efficiency and is readily deacetylated in the cytosol (31, 40). Jurkat cells were cultured in the presence of 40 μM Ac4GlcNAz for 3 days. To remove the large majority of complex glycoproteins found on the surface of the cell and within the secretory pathway, we prepared purified samples of nuclear proteins by using hypotonic swelling and Dounce homogenization followed by differential centrifugation through a sucrose gradient (41). Nuclear protein extracts were prepared by sonication of the purified nuclei in the presence of solubilizing detergents followed by centrifugation. The resulting protein supernatant was reacted with FLAG-phosphine (9, Fig. 4A) (30), subjected to SDS/PAGE, and electroblotted to nitrocellulose. Detection of FLAG phosphine-modified glycoproteins was accomplished by Western blot using a mouse anti-FLAG-mAb conjugated to HRP.

No signal was detected for the sample derived from cells that had not been treated with Ac4GlcNAz, indicating the exquisite selectivity of this phosphine probe for the azide moiety over all proteinaceous functional groups (Fig. 4E). For the sample derived from cells treated with Ac4GlcNAz, however, a large number of modified proteins were observed and represent those species that bear the O-GlcNAz modification. These observations are consistent with the observation that the enzymes of the salvage and O-GlcNAc modification pathways are tolerant of the N-azidoacetyl moiety.

Incorporation of GlcNAz into Nuclear Pore Protein p62 in Jurkat Cells. To further validate the method, we analyzed a specific protein from GlcNAz-treated cells that is known to be modified with O-GlcNAc under normal conditions. The nuclear pore protein p62 is known to be associated with the nuclear envelope and is consequently isolated in preparations of solubilized nuclear extracts (6, 8). Furthermore, we have already demonstrated that OGTase catalyzes the glycosylation of p62 by using the unnatural donor sugar UDP-GlcNAz in vitro. Jurkat cells were cultured in the presence and absence of Ac4GlcNAz, harvested by centrifugation, and lysed under denaturing conditions. Immunoprecipitation of nuclear pore protein p62 and detection of the immunoprecipitated protein by Western blot with an anti-p62 mAb (6) showed that p62 was present in comparable amounts in cells cultured in the presence or absence of Ac4GlcNAz (Fig. 4F, the same blot as in Fig. 4G but stripped and reprobed with anti-p62 mAb). The immunoprecipitated samples were either digested with O-GlcNAcase or treated with buffer overnight. Samples were then reacted with FLAG-phosphine (9, Fig. 4A) and analyzed by Western blot with anti-FLAG-HRP. As shown in Fig. 4G, only the cells incubated with Ac4GlcNAz produced p62 bearing the azide moiety. Furthermore, digestion of samples with O-GlcNAcase markedly abrogated the signal arising from ligation of O-GlcNAz to FLAG-phosphine (although some residual signal could be observed during increased film exposure times) and also caused a slight increase in migration of the digested protein (Fig. 4F). This result is consistent with the in vitro data showing that GlcNAz-derived substrates are cleaved by O-GlcNAcase. A similarly small increase in migration of p62 was observed after digestion of p62 by jack bean hexosaminidase (6) and is consistent with the enzymatic removal of a number of GlcNAc residues from the protein. Indeed, p62 is known to bear >10 O-GlcNAc modification sites (37). On the basis of these results it is apparent that p62 is being modified with GlcNAz in place of GlcNAc at sites of O-GlcNAc modification. However, because p62 immunoprecipitated from cells treated with GlcNAz migrates similarly before and after reaction with FLAG-phosphine (molecular weight = 1,298), GlcNAz is most likely incorporated at substoichiometric efficiencies.

Conclusion

In summary, the enzymes of the GlcNAc salvage pathway are tolerant of an azido group pendant to the acetamido moiety of GlcNAc. Furthermore, GlcNAz can be metabolically incorporated into nuclear proteins by OGTase both in vitro and in living cells. Approaches to increasing levels of GlcNAz incorporation may include the treatment of cells with inhibitors of O-GlcNAcase such as PUGNAc (42), thereby simply increasing global levels of O-GlcNAz. Inhibitors of the initial enzymes involved in the de novo hexosamine biosynthetic pathway may be used to increase the pool of UDP-GlcNAz relative to UDP-GlcNAc. Alternatively, cells in which the de novo biosynthetic pathway has been genetically disrupted may have increased levels of UDP-GlcNAz relative to UDP-GlcNAc. The apparent substoichiometric level of GlcNAz incorporation observed here may be of some advantage in that it permits cellular functions to proceed, in some part, with the natural GlcNAc residue in place. Indeed, total replacement of GlcNAc with GlcNAz could potentially disrupt cellular function. It is noteworthy, however, that prolonged exposure of Jurkat cells to Ac4GlcNAz has no apparent toxic effects and the cells appear normal in all respects, including morphology and growth rate (31).

One of the most exciting applications of this work is in proteomic analysis of O-GlcNAc-modified proteins. Indeed, the general development of novel chemistry for functional proteomics is a topic of intense interest (43). As mentioned previously, the complete repertoire of O-GlcNAc-modified proteins has not been defined, and the specific sites of glycosylation are not known for many inventoried proteins. Some recent progress has been made, however, in the identification of proteins and the sites of O-GlcNAc modification by using an O-GlcNAc-directed antibody (39). Immunoprecipitation of O-GlcNAc-modified proteins provides an enrichment of samples for 2D gel analysis. Chemical manipulation of the gel-isolated protein has allowed the identification of the sites of modification of a small number of proteins (38). Because the azide moiety can be ligated with such high chemoselectivity, covalent trapping of peptides using the Staudinger ligation is well suited for non-gel-based proteomics methods. Furthermore, the Staudinger ligation is carried out under very mild conditions such that proteins, peptides, and other posttranslational modifications are stable. Thus, azide labeling and covalent trapping by Staudinger ligation should prove complementary to gel-based strategies, and we envision that it will provide a useful tool for the analysis of the O-GlcNAc modification. The development of an efficient method for comparative proteomics of O-GlcNAc-modified proteins based on azide labeling and Staudinger ligation is a major future goal. Finally, the Staudinger ligation may be used more generally to probe other posttranslational modifications, such as lipids, for which a synthetic azido precursor can enter a cellular metabolic pathway.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank S. Hinderlich for the plasmid bearing the gene encoding GlcNAc kinase, A. Elbein for the plasmid bearing the gene encoding the UDP-GlcNAc pyrophosphorylase, and S. Luchansky for purified GlcNAc kinase and critical reading of the manuscript. D.J.V. thanks the generous support of the Canadian Institutes of Health Research for a postdoctoral fellowship. H.C.H. thanks the Organic Division of the American Chemical Society for a predoctoral fellowship. This research was supported by National Institutes of Health Grant GM066047 (to C.R.B.). The Center for New Directions in Organic Synthesis is funded by Bristol-Myers Squibb as a supporting member and Novartis as a sponsoring member.

This paper was submitted directly (Track II) to the PNAS office.

Abbreviations: OGTase, GlcNAc:polypeptidyltransferase; GlcNAz, N-azidoacetylglucosamine; HRP, horseradish peroxidase; AGM1, phospho-N-acetylglucosamine mutase.

References

- 1.Torres, C. R. & Hart, G. W. (1984) J. Biol. Chem. 259, 3308–3317. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wells, L., Vosseller, K. & Hart, G. W. (2001) Science 291, 2376–2378. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hanover, J. A. (2001) FASEB J. 15, 1865–1876. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Zachara, N. E. & Hart, G. W. (2002) Chem. Rev. 102, 431–438. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Jackson, S. P. & Tjian, R. (1988) Cell 55, 125–133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Davis, L. I. & Blobel, G. (1987) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 84, 7552–7556. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Davis, L. I. & Blobel, G. (1986) Cell 45, 699–709. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hanover, J. A., Cohen, C. K., Willingham, M. C. & Park, M. K. (1987) J. Biol. Chem. 262, 9887–9894. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Parker, G. J., Lund, K. C., Taylor, R. P. & McClain, D. A. (2003) J. Biol. Chem. 278, 10022–10027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Shafi, R., Lyer, S. P. N., Ellies, L. G., O'Donnell, N., Marek, K. W., Chui, D., Hart, G. W. & Marth, J. D. (2000) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 97, 5735–5739. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hartweck, L. M., Scott, C. L. & Olszewski, N. E. (2002) Genetics 161, 1279–1291. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lubas, W. A., Frank, D. W., Krause, M. & Hanover, J. A. (1997) J. Biol. Chem. 272, 9316–9324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kreppel, L. K. & Hart, G. W. (1997) FASEB J. 11, A1248–A1248. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kreppel, L. K. & Hart, G. W. (1999) J. Biol. Chem. 274, 32015–32022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chou, T. Y., Hart, G. W. & Dang, C. V. (1995) J. Biol. Chem. 270, 18961–18965. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cheng, X. G. & Hart, G. W. (2001) J. Biol. Chem. 276, 10570–10575. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gao, Y., Wells, L., Comer, F. I., Parker, G. J. & Hart, G. W. (2001) J. Biol. Chem. 276, 9838–9845. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Love, D. C., Kochan, J. P., Cathey, R. L., Shin, S.-H. & Hanover, J. A. (2003) J. Cell Sci. 116, 647–654. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hanover, J. A., Yu, S., Lubas, W. B., Shin, S. H., Ragano-Caracciola, M., Kochran, J. & Love, D. C. (2003) Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 409, 287–297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.McClain, D. A., Lubas, W. A., Cooksey, R. C., Hazel, M., Parker, G. J., Love, D. C. & Hanover, J. A. (2002) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 99, 10695–10699. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Vosseller, K., Wells, L., Lane, M. D. & Hart, G. W. (2002) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 99, 5313–5318. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Rossetti, L. (2000) Endocrinology 141, 1922–1925. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Yki-Jarvinen, H., Virkamaki, A., Daniels, M. C., McClain, D. A. & Gottschalk, W. K. (1998) Metabolism 47, 449–455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Federici, M., Menghini, R., Maurielle, A., Hribal, M. L., Ferrelli, F., Lauro, D., Sbraccia, P., Spagnoli, L. G., Sesti, G. & Lauro, G. (2002) Circulation 106, 466–472. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Vosseller, K., Wells, L. & Hart, G. W. (2001) Biochimie 83, 575–581. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Boehmelt, G., Wakeham, A., Elia, A., Sasaki, T., Plyte, S., Potter, J., Yang, Y. J., Tsang, E., Ruland, J., Iscove, N. N., et al. (2000) EMBO J. 19, 5092–5104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Keppler, O. T., Horstkorte, R., Pawlita, M., Schmidt, C. & Reutter, W. (2001) Glycobiology 11, 11R–18R. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Brossmer, R. & Gross, H. J. (1994) Methods Enzymol. 247, 153–176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Luchansky, S. J., Hang, H. C., Saxon, E., Grunwell, J. R., Yu, C., Dube, D. H. & Bertozzi, C. R. (2003) Methods Enzymol., in press. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 30.Saxon, E. & Bertozzi, C. R. (2000) Science 287, 2007–2010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Saxon, E., Luchansky, S. J., Hang, H. C., Yu, C., Lee, S. C. & Bertozzi, C. R. (2002) J. Am. Chem. Soc. 124, 14893–14902. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Luchansky, S. J., Yarema, K. J., Takahashi, S. & Bertozzi, C. R. (2002) J. Biol. Chem. 278, 8035–8042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hinderlich, S., Berger, M., Schwarzkopf, M., Effertz, K. & Reutter, W. (2000) Eur. J. Biochem. 267, 3301–3308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Mio, T., Yamada-Okabe, T., Arisawa, M. & Yamada-Okabe, H. (2000) Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1492, 369–376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wang-Gillam, A., Pastuszak, I. & Elbein, A. D. (1998) J. Biol. Chem. 273, 27055–27057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Broschat, K. O., Gorka, C., Page, J. D., Martin-Berger, C. L., Davies, M. S., Huang Hc, H. C., Gulve, E. A., Salsgiver, W. J. & Kasten, T. P. (2002) J. Biol. Chem. 277, 14764–14770. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lubas, W. A., Smith, M., Starr, C. M. & Hanover, J. A. (1995) Biochemistry 34, 1686–1694. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wells, L., Vosseller, K., Cole, R. N., Cronshaw, J. M., Matunis, M. J. & Hart, G. W. (2002) Mol. Cell. Proteomics 1, 791–804. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Comer, F. I., Vosseller, K., Wells, L., Accavitti, M. A. & Hart, G. W. (2001) Anal. Biochem. 293, 169–177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Jacobs, C. L., Yarema, K. J., Mahal, L. K., Nauman, D. A., Charter, N. W. & Bertozzi, C. R. (2000) Methods Enzymol. 327, 260–275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Spann, T. P. (1998) Cells: A Laboratory Manual (Cold Spring Harbor Lab. Press, Plainview, NY).

- 42.Haltiwanger, R. S., Grove, K. & Philipsberg, G. A. (1998) J. Biol. Chem. 273, 3611–3617. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Griffin, T. J., Goodlett, D. R. & Aebersold, R. (2001) Curr. Opin. Biotechnol. 12, 607–612. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.