Abstract

Background

Upregulation of the endo-β-d-glucuronidase, heparanase, was noted in an increasing number of human malignancies. Heparanase expression correlated with enhanced local and distant metastatic spread, increased vascular density, and reduced postoperative survival.

Patients and Methods

We analyzed heparanase expression in 60 patients (aged 59 ± 17 years) with malignant salivary tumors (39 males and 21 females) using immunohisto-chemistry. We applied antiheparanase antibody 733, which has previously been shown to preferentially recognize a 50-kDa active heparanase subunit over a 65-kDa latent enzyme. Thus, immunostaining can directly be correlated with enzymatic activity.

Results

Heparanase staining was positive (> 0) in 70% of tumors (42 of 60 patients) and was negative (0) in the remaining 30% (18 patients). The cumulative survival of patients diagnosed as heparanase-negative (n = 18) at 300 months was 70% (95% confidence interval = 35–88). In contrast, the cumulative survival of patients diagnosed as heparanase-positive (n = 42) at 300 months was 0% (statistically significant difference, P = .035).

Conclusions

Heparanase expression levels inversely correlate with the survival rates of salivary gland cancer patients, clearly indicating that heparanase is a reliable prognostic factor for this malignancy and an attractive target for anticancer drug development.

Keywords: Heparanase, salivary gland, tumor, malignant, survival

Introduction

The extracellular matrix (ECM) consists mainly of collagen, proteoglycans, and glycoproteins such as laminin and fibronectin; provides an essential physical barrier between cells and tissues; and provides a scaffold for cell growth, migration, differentiation, and survival. The ECM undergoes continuous remodeling during development and in certain pathological conditions, such as wound healing and cancer [1]. ECM remodeling enzymes are thus expected to profoundly affect cell and tissue functions. Heparanase is an endoglycosidase that specifically cleaves heparan sulfate (HS) side chains of HS proteoglycans [2–4]—the major proteoglycans in the ECM and cell surfaces. In addition to its structural role as a molecular link between different ECM components, contributing to ECM integrity and insolubility, HS side chains can bind a variety of biologic mediators such as growth factors, cytokines, and chemokines, thus forming a readily available reservoir that can be liberated on local or systemic cues [5–9]. Traditionally, heparanase activity was implicated in cellular invasion associated with angiogenesis, inflammation, and cancer metastasis [10–12]. This notion recently gained further support by employing siRNA and ribosome technologies, clearly depicting heparanase-mediated HS cleavage and ECM remodeling as critical requisites for angiogenesis and metastatic spread [13]. More recently, heparanase upregulation was documented in an increasing number of primary human tumors. Heparanase upregulation correlated with reduced postoperative survival of pancreatic [14], bladder [15], gastric [16], cervical [17], and colorectal [17,18] cancer patients. Similarly, heparanase upregulation correlated with increased lymph node and distant metastases [15,19–21], providing strong clinical support for the prometastatic feature of heparanase.

We examined heparanase expression (Table 1) in a series of 60 salivary gland tumor biopsies and then correlated heparanase expression with clinical and molecular parameters. Significantly, heparanase expression in salivary gland tumors inversely correlated with cumulative survival and disease-free survival (DFS), suggesting that heparanase plays an important role in the progression of this kind of cancer and can thus be considered as a novel target for the development of anticancer drugs.

Table 1.

Heparanase Expression Levels.

| Heparanase Expression* | Patients | |

| n | % | |

| 0 | 18 | 30 |

| > 0 | 42 | 70 |

| Total | 60 | 100 |

0, Negative; > 0, positive (see Figure 1 for representative cases).

Materials and Methods

Experimental Design

Sixty patients (39 males and 21 females aged 59 ± 17 years) with malignant salivary tumors were analyzed. Clinical data were collected from patients' hospitalization and follow-up records, and included tumor type and size, salivary gland involvement (parotid, submandibular, sublingual, or minor salivary glands), and lymph node metastasis (0 = negative; > 0 = positive). Twelve of the tumors were mucoepidermoid cell carcinomas, 11 were adenocarcinomas, 10 were squamous cell carcinomas, 9 were acinic cell carcinomas, 6 were adenoid cystic carcinomas, 4 were low-grade polymorphous adenocarcinomas, and 4 were anaplastic cell carcinomas. There was only one example of each of the following: malignant oncocytoma, salivary duct cell carcinoma, carcinoma ex-mixed tumor, and neuroendocrine carcinoma. All biopsies were obtained at the time of diagnosis. Five patients had extensive locally spread invasion, two had distant metastasis to the lungs, and one had distant metastasis to the brain. The immunohistologic analysis of heparanase, P27, ErbB-2, and von Willebrand factor (vWF) was performed on paraffin-embedded tumor specimens, evaluated, and scored by expert pathologists.

Immunostaining

Heparanase staining The staining of formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded 5-µm sections for heparanase was performed essentially as described [22,23]. Briefly, slides were deparaffinized with xylene and rehydrated, and endogenous peroxidase activity was quenched (30 minutes) by 3% hydrogen peroxide in methanol. They were then subjected to antigen retrieval by boiling (20 minutes) in 10 mM citrate buffer (pH 6), incubated with 10% normal goat serum (NGS) in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) for 60 minutes to block nonspecific binding, and incubated (for 20 hours at 4°C) with anti-heparanase antibody 733 diluted 1:100 in blocking solution. Antibody 733 was raised in rabbits against a 15-amino acid peptide (KKFKNSTYSRSSVDC) that maps at the C-terminus of the 50-kDa heparanase subunit [22]. Slides were then extensively washed with PBS containing 0.01% Triton X-100 and incubated with a secondary reagent (Envision kit; Dako, Glostrup, Denmark) according to the manufacturer's instructions. Following additional washes, color was developed with AEC reagent (Sigma, St. Louis, MO), and sections were counterstained with hematoxylin and mounted as described [22]. Slides were scored as heparanase-negative (0) or heparanase-positive (> 0). In all tumors diagnosed as heparanase-positive, more than 50% of cells reacted with the antiheparanase antibody.

vWF staining of vascular endothelial cells Following deparaffinization and rehydration, slides were treated with 0.1% trypsin (for 20 minutes at 37°C) and washed, and antigen retrieval was performed by boiling in 0.05% citraconic anhydride (pH 7.4; Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO) for 45 minutes [24]. Slides were washed, incubated with blocking solution (10% NGS in PBS), and stained with anti-vWF antibodies (polyclonal antibodies, diluted 1:250; Dako) using the Envision kit, as described above. vWF-positive vascular structures in three random microscopic fields were counted (in a blind manner) at high magnification (x 40).

ErbB-2 staining Staining for ErbB-2 was performed as described above, except that 10 mM citrate buffer (pH 6) was used for antigen retrieval (in a 800-W microwave oven for 15 minutes). Slides were incubated with anti ErbB-2 antibodies (polyclonal antibodies, diluted 1:4000; Dako) for 60 minutes at room temperature, followed by the application of the streptavidin-biotin method (Histostain Plus; Zymed Laboratories, South San Francisco, CA). Positive controls were run in parallel and included sections from a breast tumor that was known to overexpress ErbB-2. A negative control was obtained by substituting preimmune rabbit serum for primary antibodies. Positive staining for ErbB-2 was considered when more than 10% of tumor cells showed membranous staining. Positive staining was scored as 1+ = weak or 2+ = strong.

Statistical Analysis

Categorical variables' frequencies, percentages, and distribution were calculated. The distribution of categorical variables was compared by chi-square analysis (large sample) and Fisher-Irwin exact test (small sample). For continuous variables (age and blood vessel density), the ranges, means, standard deviations, and standard errors were calculated. The results between the continuous variables (two subgroups) were compared by t-test for differences in means. Kaplan-Meier analysis was used to calculate the probability of survival and DFS rates as a function of time in subgroups of patients specified by heparanase levels. Log-rank test was applied to perform comparisons with Kaplan-Meier analysis.

Results

Heparanase Expression in 60 Patients with Salivary Gland Tumors

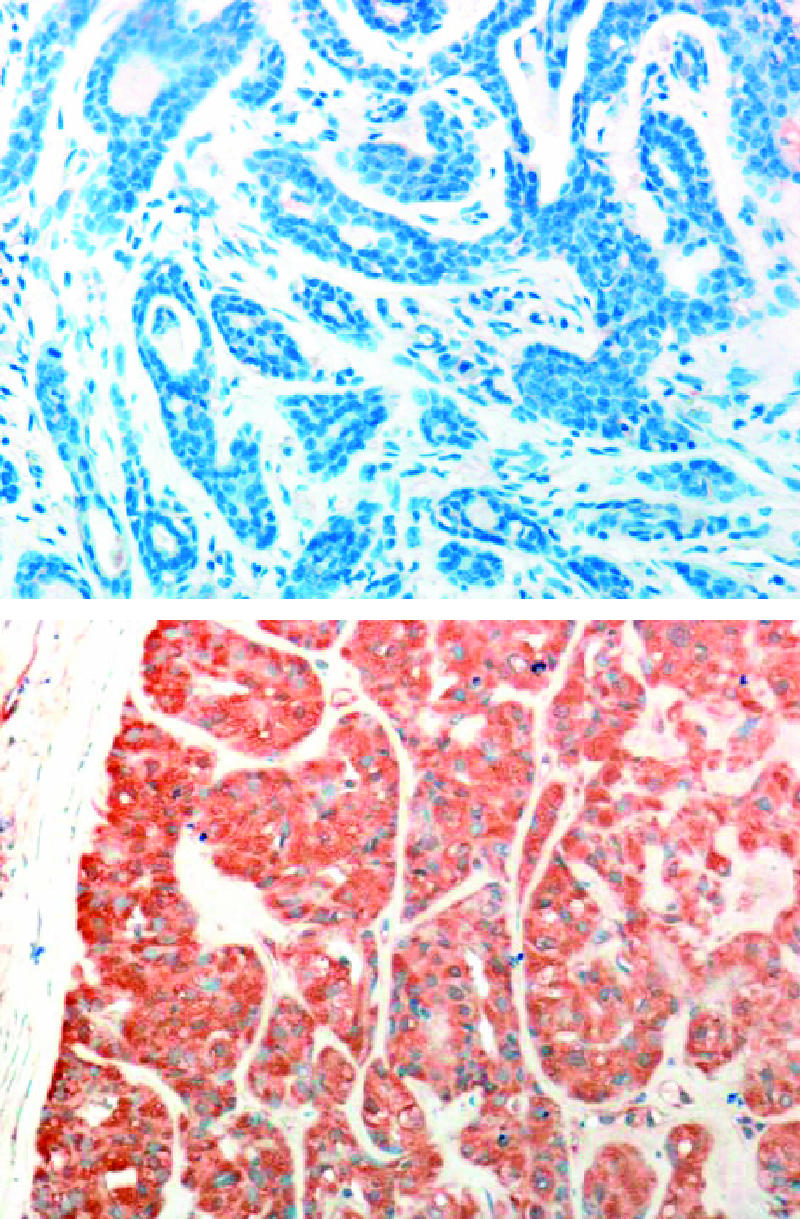

Heparanase activity has long been correlated with the metastatic potential of tumor-derived cells [9,11,12]. Since the cloning of the heparanase gene and the availability of specific molecular probes, heparanase upregulation has been documented in an increasing number of primary human tumors by means of in situ hybridization and immunostaining. Recently, we developed a polyclonal antibody (pAb 733) that preferentially recognizes the 50-kDa heparanase subunit of 50 + 8 active heterodimer enzyme over the latent 65-kDa protein and used this antibody to study heparanase processing, trafficking route, and cellular localization [22]. Furthermore, this antibody is suitable for the staining of paraffin sections [22]. Thus, immunostaining of archival materials can directly be correlated with heparanase enzymatic activity. We employed antibody 733 to examine heparanase expression in 60 salivary gland tumor specimens. Heparanase staining was positive (> 0) in 70% (42 patients) of tumors and negative (0) in the remaining 30% (18 patients). All control healthy tissues stained negatively for heparanase. Representative photomicrographs of heparanase-negative (upper panel) and heparanase-positive (lower panel) tumor biopsies are shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Immunohistochemical staining of heparanase in patients with salivary gland tumors. Formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded 5-µm sections of salivary gland tumors were subjected to immunostaining of heparanase, applying antiheparanase pAb 733 as described in the Materials and Methods section. Representative photomicrographs of heparanase-negative (upper panel) and heparanase-positive (lower panel) stainings are shown.

Heparanase Expression according to Age, Gender, Tumor Size, and Lymph Node Metastasis

No significant correlations were demonstrated between the level of heparanase staining and either the age or gender of patients. Similarly, no significant correlation was observed between heparanase staining level and either the type of tumor of the salivary gland involved (Table 2) or the tumor size (Table 3) and lymph node metastasis. Two (11%) of 17 patients stained negative for heparanase (0), and 8 (21%) of 38 patients diagnosed as heparanase-positive had lymph node metastases (> 0; P = .34).

Table 2.

Heparanase Expression in Different Salivary Gland Tumors (P = .26).

| Heparanase/Gland | Patients [n (%)] | |

| 0 | > 0 | |

| Parotid | 11 (61) | 23 (54) |

| Submandibular | 0 | 7 (17) |

| Minor (hard palate) | 2 (11) | 7 (17) |

| Sublingual | 1 (6) | 1 (2) |

| Minor (oral) | 4 (22) | 4 (10) |

| Total | 18 (100) | 42 (100) |

Table 3.

Heparanase Levels and Tumor Size (P = .20).

| Heparanase/Tumor Size | Patients [n (%)] | |

| 0 | >0 | |

| 1 | 3 (17) | 16 (38) |

| 2 | 8 (44) | 15 (36) |

| 3 | 3 (17) | 1 (3) |

| 4 | 3 (17) | 6 (14) |

| ND | 1 (5) | 4 (9) |

| Total | 18 (100) | 42 (100) |

1, < 2 cm; 2, < 4 cm; 3, < 6 cm; 4, > 6 cm.

ND, not determined.

Heparanase and c-ErbB-2 Immunostaining

Fifteen (83%) of 18 salivary gland tumor specimens that were found negative for heparanase were also negative for ErbB-2 expression, whereas the other three (17%) cases exhibited weak ErbB-2 staining (1+; Table 4). Similarly, the majority (74%) of heparanase-positive cases were negative for ErbB-2 expression (Table 4), suggesting that ErbB-2 is not a clinical parameter for salivary gland tumors, in agreement with our previous finding [25]. Interestingly, four (10%) heparanase-positive salivary gland tumor specimens and none of the heparanase-negative specimens exhibited high levels of ErbB-2 staining (2+; Table 4).

Table 4.

Heparanase and c-ErbB-2 Expression Levels (P = .037).

| Heparanase/c-ErbB-2 | Patients [n (%)] | |

| 0 | > 0 | |

| 0 | 15 (83) | 31 (74) |

| 1 | 3 (17) | 1 (2) |

| 2 | 0 | 4 (10) |

| ND | 0 | 6 (14) |

| Total | 18 (100) | 42 (100) |

ND, not determined.

Heparanase Expression Level and Blood Vessel Density

Heparanase has previously been considered as a proangiogenic mediator due to its ability to release HS-bound angiogenic growth factors, such as basic fibroblast growth factor and vascular endothelial growth factor, sequestered in the ECM [7,9,26]. In fact, increased vessel density correlated with heparanase expression levels in several human tumors [15,19,27,28]. The staining of vascular endothelial cells with anti-vWF antibody revealed a mean of 11.5 blood vessels per high-power field in heparanase-negative specimens vs 15.3 blood vessels per high-power field in heparanase-positive tumor specimens (Table 5). Although not statistically significant, these results agree with the notion that heparanase functions as a proangiogenic mediator.

Table 5.

Blood Vessel Density and Heparanase Staining Levels (P = .14).

| Heparanase/Blood Vessels | Patients [n (%)] | |

| 0 (n = 5) | > 0 (n = 17) | |

| Range | 6.0–22.0 | 4.7–31.0 |

| Mean vessel density | 11.5 | 15.3 |

| Standard error | 2.9 | 1.6 |

Sections of salivary gland tumors were stained with anti-vWF antibodies, as described in the Materials and Methods section. vWF-positive vascular structures in three random fields were counted (in a blind manner) at high magnification (x 40).

Heparanase and Postoperative Survival

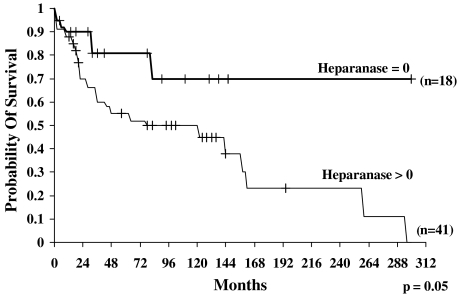

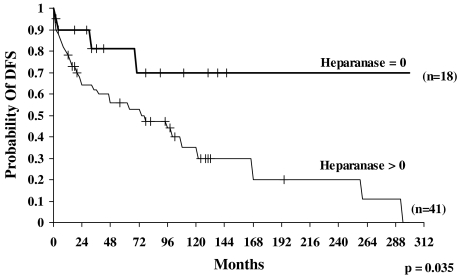

To determine the prognostic value of heparanase in salivary gland cancer, we analyzed the probability of survival and the DFS of patients following curative resection. The probability of survival of patients diagnosed as heparanase-negative (n = 18) at 300 months (25 years) was 70% [95% confidence interval (95% CI) = 35–88]. In contrast, the probability of survival of patients found to express heparanase (n = 41) at 300 months was 0% (statistically significant difference, P = .05) (Figure 2). Similarly, the probability of DFS of patients diagnosed as heparanase-negative (0; n = 18) at 300 months (25 years) was 70% (95% CI = 37–88) (Figure 3), whereas the probability of DFS of patients expressing heparanase (n = 41) at 300 months was 0% (statistically significant difference, P = .035) (Figure 3). Thus, heparanase expression levels inversely correlate with the survival rates of salivary gland cancer patients, clearly indicating that heparanase is a reliable prognostic factor for this malignancy.

Figure 2.

Overall survival curves of patients with salivary gland tumors according to heparanase immunostaining levels. Kaplan-Meier analysis showed poor survival of patients with positive heparanase expression, compared with patients who were diagnosed as heparanase-negative. After 300 months (25 years) of follow-up, 0% of heparanase-positive patients survived, compared with 70% of patients with no detectable heparanase expression (P = .05).

Figure 3.

DFS curves of patients with salivary gland tumors according to heparanase expression levels. Kaplan-Meier analysis showed significantly poor survival in patients with positive heparanase staining, compared with patients with negative (0) heparanase expression. After 300 months (25 years) of follow-up, 0% of patients with positive heparanase staining survived, compared with 70% of patients with negative staining (P = .035).

Lymph Node Metastasis and Postoperative Survival

To determine the impact of lymph node metastasis on the survival of patients with salivary gland cancer, we analyzed the probability of survival of patients in correlation with lymph node metastasis. The probability of survival of patients diagnosed as free of lymph node metastasis (0; n = 44) was 86% at 24 months (95% CI = 71–93) and 14% (95% CI = 6–56) at 300 months (25 years). In contrast, the probability of survival of patients diagnosed with positive lymph node metastasis (> 0; n = 10) was 0% at 24 months and 0% at 300 months. The probability of survival of patients diagnosed with negative lymph node metastases (0) was significantly higher than that of patients diagnosed with positive lymph node metastasis (> 0; P = .0001).

Discussion

Salivary gland neoplasms are relatively rare, accounting for 5% of tumors arising in the head and neck region. The frequency of these tumors is ∼0.5 per 100,000; the majority arise in the parotid gland (70%) and, of these, 25% are malignant. Of those tumors arising in the salivary glands, 50% are malignant. Surgical resection is the primary treatment for this malignancy, whereas radiation therapy is usually applied on patients with advanced disease. Chemotherapy has been reserved for patients with incurable salivary neoplasm, with a typical response rate of 15% to 30% [29]. Given the variability and complexity of these tumors, a better understanding of its basic biology is required to define relevant targets for the development of novel therapeutic approaches. For the first time, we examined heparanase expression in a series of 60 salivary tumor biopsies. Heparanase upregulation was noted in 70% of cases (Table 1, Figure 1), in agreement with previous reports documenting an increased heparanase expression in malignancies of the breast, colon, pancreas, bladder, gastrointestinal tract, and liver [14,15,18,20,21,27,30]. Clearly, heparanase upregulation inversely correlates with the postoperative survival of patients with salivary gland tumors, as indicated by probability of survival (Figure 2) and DFS (Figure 3) analyses. This finding is in agreement with enhanced metastatic spread and reduced postoperative survival noted for several other human cancers overexpressing heparanase [15,16,19–21], collectively providing a strong clinical support for the prometastatic function of heparanase. The significance of heparanase as a prognostic factor in patients with salivary gland neoplasms is best demonstrated by the finding that the cumulative survival of patients who express heparanase was zero. These observations and the occurrence of a single functional human heparanase gene [31–34] strongly suggest that the enzyme is an attractive target for the development of anticancer drugs. Given the unique feature of antibody 733 that preferentially recognizes the 50-kDa subunit, the staining of tumor biopsies can directly be correlated with the enzymatic activity of heparanase.

Enhanced metastatic spread involves tumor blood and lymphatic vessels. Indeed, increased microvessel density correlated with heparanase upregulation in patients with hepatocellular [27], bladder [15], cervical [17], and colorectal [19] carcinomas, as well as in those with multiple myeloma [28]. This proangiogenic feature of heparanase was recapitulated in several in vitro and in vivo model systems [13,35–37]. The increase in blood vessel density observed in heparanase-positive salivary gland carcinoma (Table 5) is in agreement with this trend, although it was not statistically significant, most likely due to the small number of samples available for staining and the internal variability of the salivary tumor subtypes analyzed (Table 2). These factors may also explain the lack of significant correlation between heparanase expression and lymph node metastasis.

The upregulation of epidermal growth factor (EGF) receptors, most often ErbB-1 and ErbB-2, is implicated in the progression of several human carcinomas, and small molecule inhibitors or neutralizing antibodies directed against these receptors are successfully applied in clinics. ErbB-2, however, was detected only in a small number of salivary gland tumor biopsies (Table 4) and is thus not likely to play a pivotal role in the progression of this cancer [25,29]. Interestingly, 10% of salivary gland tumor biopsies that were diagnosed as heparanase-positive were noted to express high levels (2+) of ErbB-2, whereas none of the heparanase-negative specimens was diagnosed as such (Table 4). Thus, a correlation between the expression of heparanase and EGF receptors should better be investigated in carcinomas where EGF receptors are clinically implicated, such as in carcinoma of the breast. For the first time, the results demonstrate heparanase induction in salivary gland tumors and predict poor prognosis for patients who express heparanase, further emphasizing the notion that heparanase is a valid target for the development of anticancer drugs.

Footnotes

This work was supported by grant 532/02 from the Israel Science Foundation; grant RO1-CA 106456 from the National Cancer Institute, National Institutes of Health; the Israel Cancer Research Fund; and the Rappaport Family Institute Fund.

References

- 1.Werb Z. ECM and cell surface proteolysis: regulating cellular ecology. Cell. 1997;91:439–442. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80429-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Vlodavsky I, Friedmann Y. Molecular properties and involvement of heparanase in cancer metastasis and angiogenesis. J Clin Invest. 2001;108:341–347. doi: 10.1172/JCI13662. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Parish CR, Freeman C, Hulett MD. Heparanase: a key enzyme involved in cell invasion. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2001;1471:M99–M108. doi: 10.1016/s0304-419x(01)00017-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dempsey LA, Brunn GJ, Platt JL. Heparanase, a potential regulator of cell-matrix interactions. Trends Biochem Sci. 2000;25:349–351. doi: 10.1016/s0968-0004(00)01619-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cardin AD, Weintraub HJ. Molecular modeling of protein-glycosaminoglycan interactions. Arteriosclerosis. 1989;9:21–32. doi: 10.1161/01.atv.9.1.21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Capila I, Linhardt RJ. Heparin-protein interactions. Angew Chem Int Ed Engl. 1992;41:391–412. doi: 10.1002/1521-3773(20020201)41:3<390::aid-anie390>3.0.co;2-b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Folkman J, Klagsbrun M, Sasse J, Wadzinski M, Ingber D, Vlodavsky I. A heparin-binding angiogenic protein—basic fibroblast growth factor—is stored within basement membrane. Am J Pathol. 1988;130:393–400. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bernfield M, Gotte M, Park PW, Reizes O, Fitzgerald ML, Lincecum J, Zako M. Functions of cell surface heparan sulfate proteoglycans. Annu Rev Biochem. 1999;68:729–777. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.68.1.729. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Vlodavsky I, Folkman J, Sullivan R, Fridman R, Ishai-Michaeli R, Sasse J, Klagsbrun M. Endothelial cell-derived basic fibroblast growth factor: synthesis, deposition into subendothelial extracellular matrix. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1987;84:2292–2296. doi: 10.1073/pnas.84.8.2292. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Vlodavsky I, Fuks Z, Bar-Ner M, Ariav Y, Schirrmacher V. Lymphoma cells mediated degradation of sulfated proteoglycans in the subendothelial extracellular matrix: relation to tumor cell metastasis. Cancer Res. 1983;43:2704–2711. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Nakajima M, Irimura T, DiFerrante D, DiFerrante N, Nicolson GL. Heparan sulfate degradation: relation to tumor invasion and metastatic properties of mouse B 16 melanoma sublines. Science (Washington, DC) 1983;220:611–613. doi: 10.1126/science.6220468. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Nakajima M, Irimura T, Di Ferrante N, Nicolson GL. Metastatic melanoma cell heparanase. Characterization of heparan sulfate degradation fragments produced by B16 melanoma endoglucuronidase. J Biol Chem. 1984;259:2283–2290. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Edovitsky E, Elkin M, Zcharia E, Peretz T, Vlodavsky I. Heparanase gene silencing, tumor invasiveness, angiogenesis, and metastasis. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2004;96:1219–1230. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djh230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Koliopanos A, Friess H, Kleeff J, Shi X, Liao Q, Pecker I, Zimmerman A, Buchler MW. Heparanase expression in primary and metastatic pancreatic cancer. Cancer Res. 2001;61:4655–4659. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gohji K, Hirano H, Okamoto M, Kitazawa S, Toyoshima M, Dong J, Katsuoka Y, Nakajima M. Expression of three extracellular matrix degradative enzymes in bladder cancer. Int J Cancer. 2001;95:295–301. doi: 10.1002/1097-0215(20010920)95:5<295::aid-ijc1051>3.0.co;2-a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Tang W, Nakamura Y, Tsujimoto M, Sato M, Wang X, Kurozumi K, Nakahara M, Nakao K, Nakamura M, Mori I, et al. Heparanase: a key enzyme in invasion and metastasis of gastric carcinoma. Mod Pathol. 2002;15:593–598. doi: 10.1038/modpathol.3880571. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Shinyo Y, Kodama J, Hongo A, Yoshinouchi M, Hiramatsu Y. Heparanase expression is an independent prognostic factor in patients with invasive cervical cancer. Ann Oncol. 2003;14:1505–1510. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdg407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Friedmann Y, Vlodavsky I, Aingorn H, Aviv A, Peretz T, Pecker I, Pappo O. Expression of heparanase in normal, dysplastic, and neoplastic human colonic mucosa and stroma. Evidence for its role in colonic tumorigenesis. Am J Pathol. 2000;157:1167–1175. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)64632-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sato T, Yamaguchi A, Goi T, Hirono Y, Takeuchi K, Katayama K, Matsukawa S. Heparanase expression in human colorectal cancer and its relationship to tumor angiogenesis, hematogenous metastasis, and prognosis. J Surg Oncol. 2004;87:174–181. doi: 10.1002/jso.20097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rohloff J, Zinke J, Schoppmeyer K, Tannapfel A, Witzigmann H, Mossner J, Wittekind C, Caca K. Heparanase expression is a prognostic indicator for postoperative survival in pancreatic adenocarcinoma. Br J Cancer. 2002;86:1270–1275. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6600232. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Takaoka M, Naomoto Y, Ohkawa T, Uetsuka H, Shirakawa Y, Uno F, Fujiwara T, Gunduz M, Nagatsuka H, Nakajima M, et al. Heparanase expression correlates with invasion and poor prognosis in gastric cancers. Lab Invest. 2003;83:613–622. doi: 10.1097/01.lab.0000067482.84946.bd. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zetser A, Levy-Adam F, Kaplan V, Gingis-Velitski S, Bashenko Y, Schubert S, Flugelman MY, Vlodavsky I, Ilan N. Processing and activation of latent heparanase occurs in lysosomes. J Cell Sci. 2004;117:2249–2258. doi: 10.1242/jcs.01068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Goldshmidt O, Yeikilis R, Mawasi N, Paizi M, Gan N, Ilan N, Pappo O, Vlodavsky I, Spira G. Heparanase expression during normal liver development and following partial hepatectomy. J Pathol. 2004;203:594–602. doi: 10.1002/path.1554. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Namimatsu S, Ghazizadeh M, Sugisaki Y. Reversing the effects of formalin fixation with citraconic anhydride and heat: a universal antigen retrieval method. J Histochem Cytochem. 2005;53:3–11. doi: 10.1177/002215540505300102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Nagler RM, Kerner H, Ben-Eliezer S, Minkov I, Ben-Itzhak O. Prognostic role of apoptotic, Bcl-2, c-erbB-2 and p53 tumor markers in salivary gland malignancies. Oncology. 2003;64:389–398. doi: 10.1159/000070298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bashkin P, Doctrow S, Klagsbrun M, Svahn CM, Folkman J, Vlodavsky I. Basic fibroblast growth factor binds to subendothelial extracellular matrix and is released by heparitinase and heparinlike molecules. Biochemistry. 1989;28:1737–1743. doi: 10.1021/bi00430a047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.El-Assal ON, Yamanoi A, Ono T, Kohno H, Nagasue N. The clinicopathological significance of heparanase and basic fibroblast growth factor expressions in hepatocellular carcinoma. Clin Cancer Res. 2001;7:1299–1305. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kelly T, Miao H-Q, Yang Y, Navarro E, Kussie P, Huang Y, MacLeod V, Casciano J, Joseph L, Zhan F, et al. High heparanase activity in multiple myeloma is associated with elevated microvessel density. Cancer Res. 2003;63:8749–8756. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Haddad R, Colevas AD, Krane JF, Cooper D, Glisson B, Amrein PC, Weeks L, Costello R, Posner M. Herceptin in patients with advanced or metastatic salivary gland carcinomas. A phase II study. Oral Oncol. 2003;39:724–727. doi: 10.1016/s1368-8375(03)00097-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Maxhimer JB, Quiros RM, Stewart R, Dowlatshahi K, Gattuso P, Fan M, Prinz RA, Xu X. Heparanase-1 expression is associated with the metastatic potential of breast cancer. Surgery. 2002;132:326–333. doi: 10.1067/msy.2002.125719. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Vlodavsky I, Friedmann Y, Elkin M, Aingorn H, Atzmon R, Ishai-Michaeli R, Aviv A, Pecker I, Friedmann Y. Mammalian heparanase: gene cloning, expression and function in tumor progression and metastasis. Nat Med. 1999;5:793–802. doi: 10.1038/10518. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hulett MD, Freeman C, Hamdorf BJ, Baker RT, Harris MJ, Parish CR. Cloning of mammalian heparanase, an important enzyme in tumor invasion and metastasis. Nat Med. 1999;5:803–809. doi: 10.1038/10525. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Toyoshima M, Nakajima M. Human heparanase. Purification, characterization, cloning, and expression. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:24153–24160. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.34.24153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kussie PH, Hulmes JD, Ludwig DL, Patel S, Navarro EC, Seddon AP, Giorgo NA, Bohlen P. Cloning and functional expression of a human heparanase gene. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1999;261:183–187. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1999.0962. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Elkin M, Ilan N, Ishai-Michaeli R, Friedmann Y, Papo O, Pecker I, Vlodavsky I. Heparanase as mediator of angiogenesis: mode of action. FASEB J. 2001;15:1661–1663. doi: 10.1096/fj.00-0895fje. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Gingis-Velitski S, Zetser A, Flugelman MY, Vlodavsky I, Ilan N. Heparanase induces endothelial cell migration via protein kinase B/Akt activation. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:23536–23541. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M400554200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Zcharia E, Zilka R, Yaar A, Yacoby-Zeevi O, Zetser A, Metzger S, Sarid R, Naggi A, Casu B, Ilan N, et al. Heparanase accelerates wound angiogenesis and wound healing in mouse and rat models. FASEB J. 2005;19:211–221. doi: 10.1096/fj.04-1970com. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]