Abstract

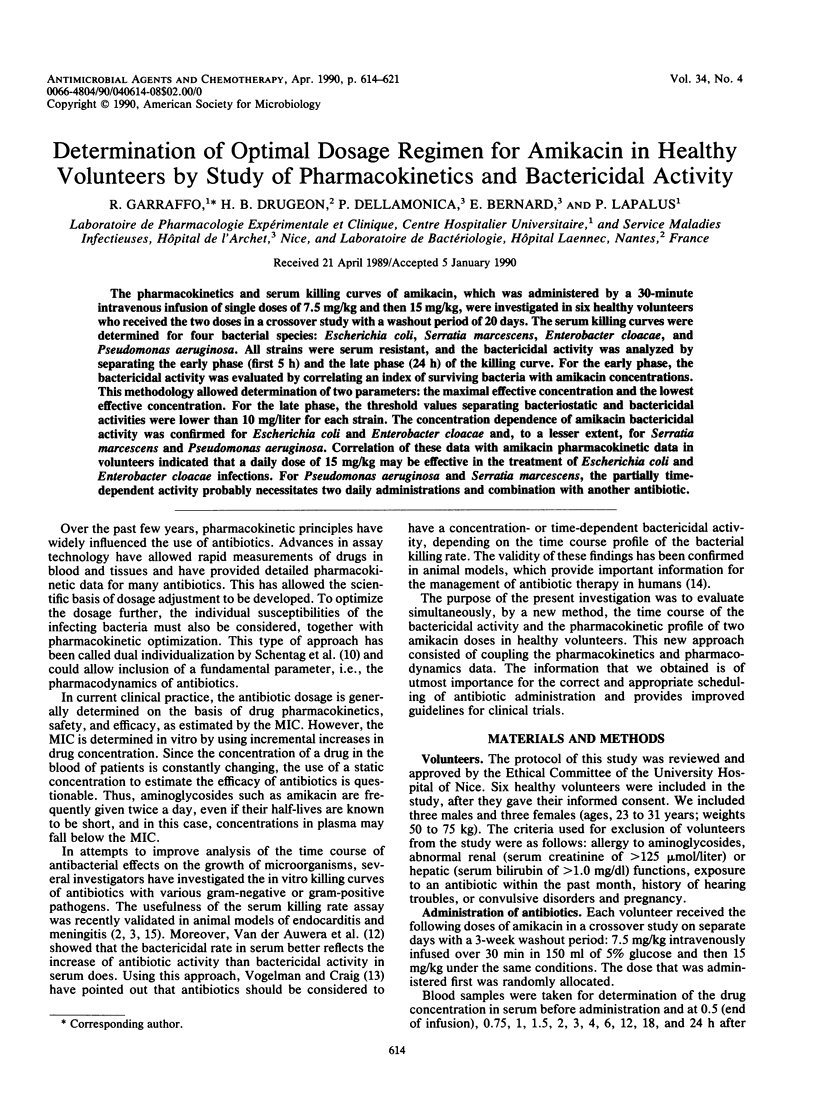

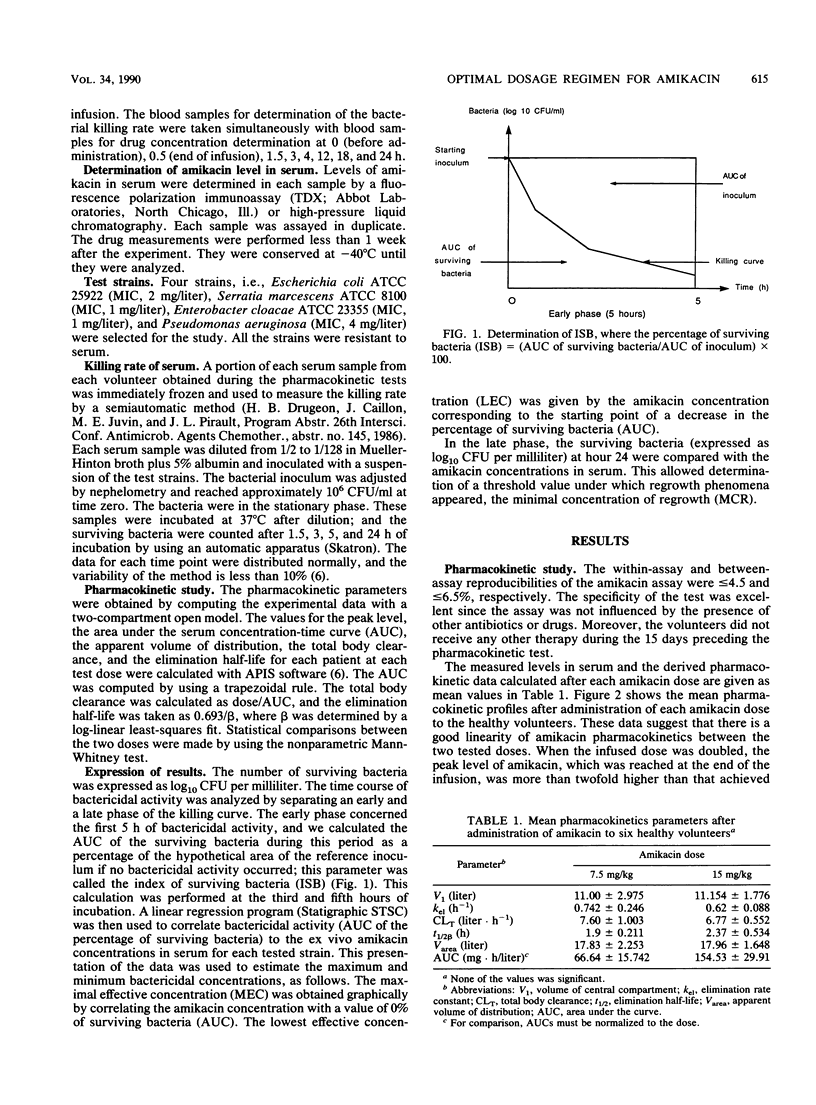

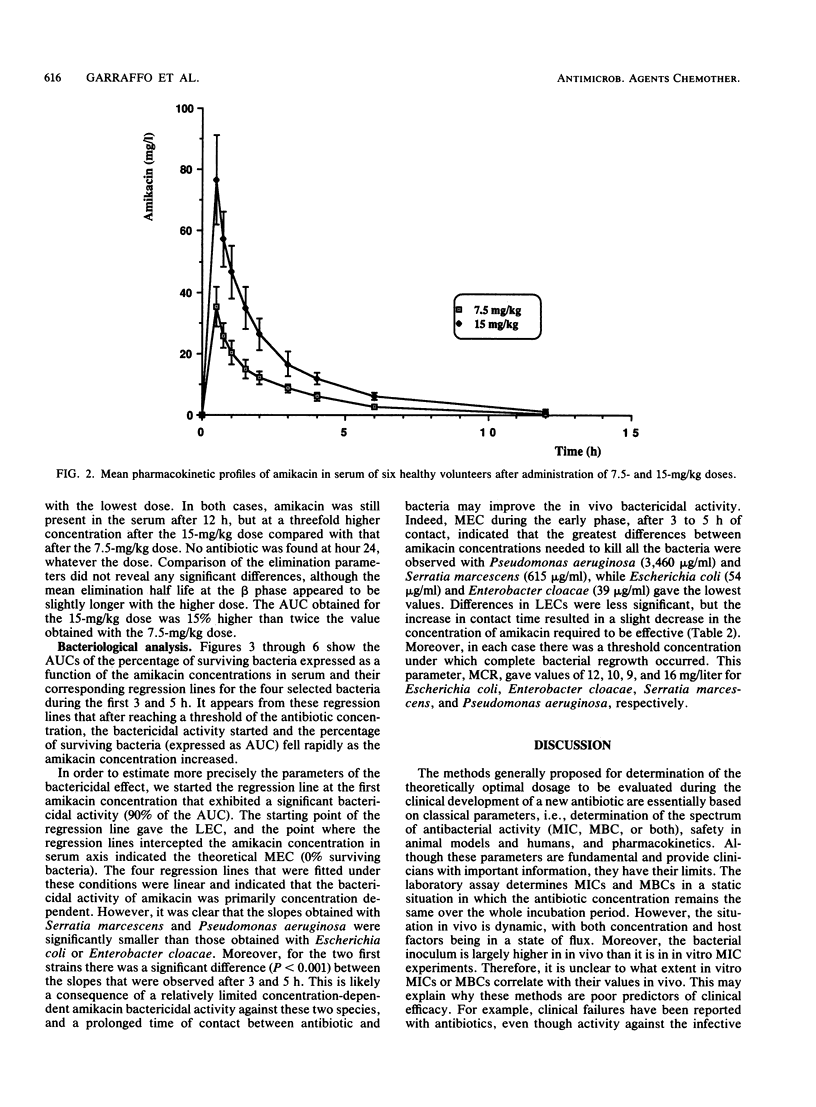

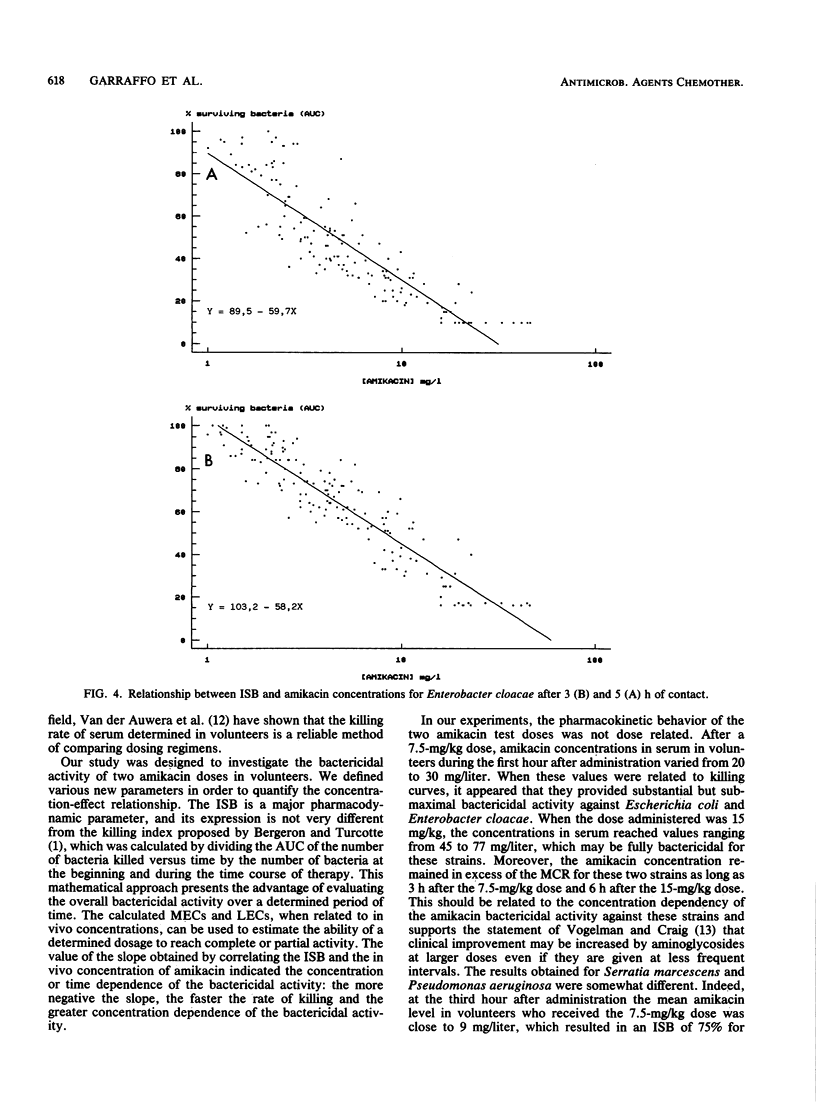

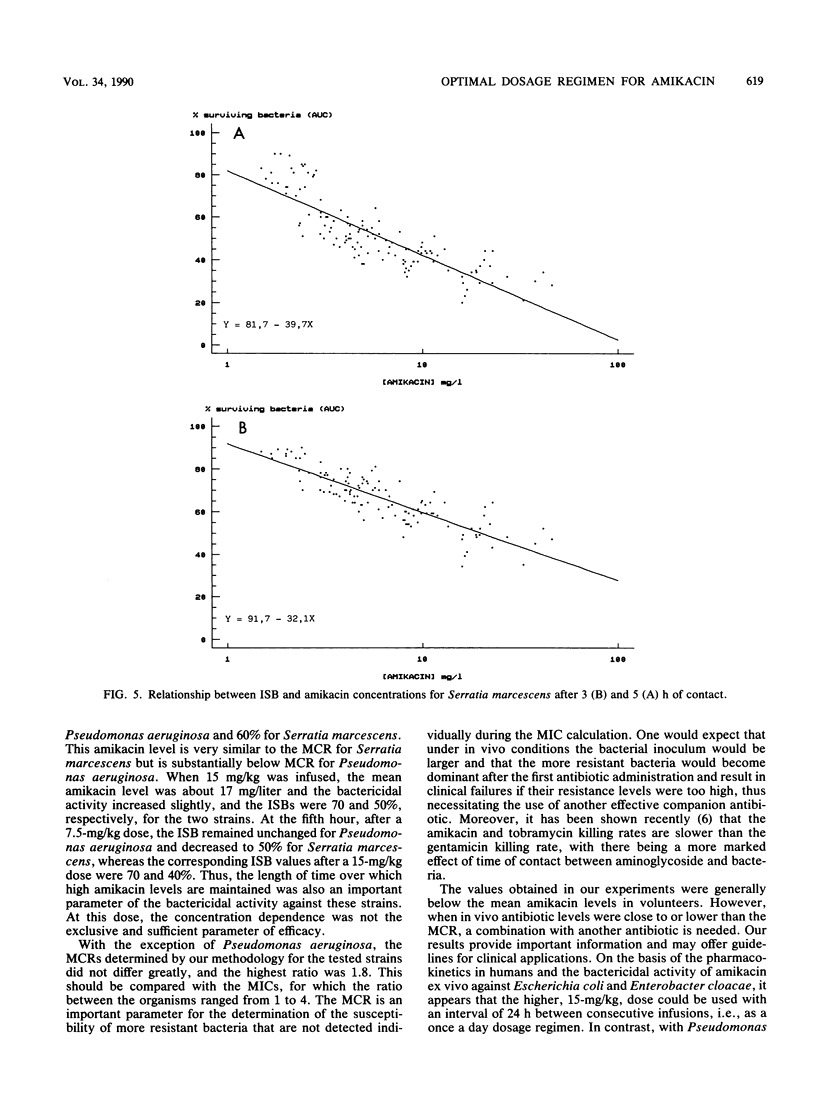

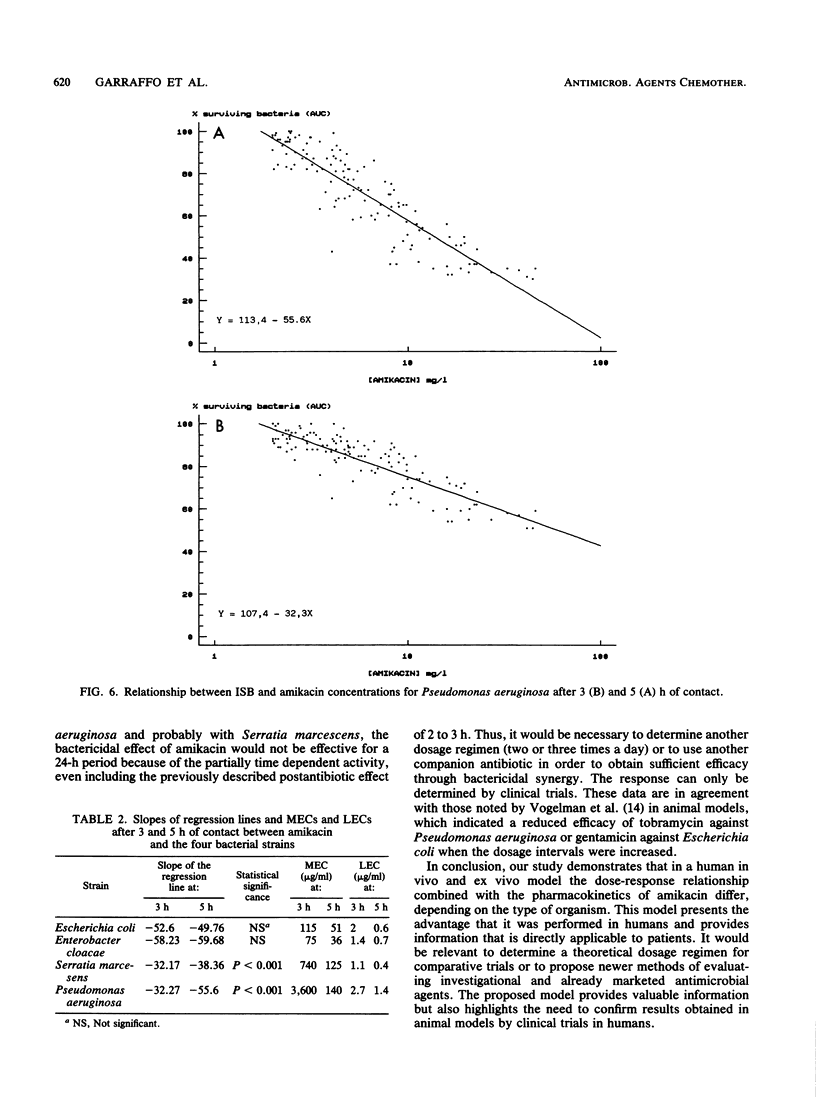

The pharmacokinetics and serum killing curves of amikacin, which was administered by a 30-minute intravenous infusion of single doses of 7.5 mg/kg and then 15 mg/kg, were investigated in six healthy volunteers who received the two doses in a crossover study with a washout period of 20 days. The serum killing curves were determined for four bacterial species: Escherichia coli, Serratia marcescens, Enterobacter cloacae, and Pseudomonas aeruginosa. All strains were serum resistant, and the bactericidal activity was analyzed by separating the early phase (first 5 h) and the late phase (24 h) of the killing curve. For the early phase, the bactericidal activity was evaluated by correlating an index of surviving bacteria with amikacin concentrations. This methodology allowed determination of two parameters: the maximal effective concentration and the lowest effective concentration. For the late phase, the threshold values separating bacteriostatic and bactericidal activities were lower than 10 mg/liter for each strain. The concentration dependence of amikacin bactericidal activity was confirmed for Escherichia coli and Enterobacter cloacae and, to a lesser extent, for Serratia marcescens and Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Correlation of these data with amikacin pharmacokinetic data in volunteers indicated that a daily dose of 15 mg/kg may be effective in the treatment of Escherichia coli and Enterobacter cloacae infections. For Pseudomonas aeruginosa and Serratia marcescens, the partially time-dependent activity probably necessitates two daily administrations and combination with another antibiotic.

Full text

PDF

Selected References

These references are in PubMed. This may not be the complete list of references from this article.

- Bergeron M. G., Turcotte A. Penetration of cefixime into fibrin clots and in vivo efficacy against Escherichia coli, Klebsiella pneumoniae, and Staphylococcus aureus. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1986 Dec;30(6):913–916. doi: 10.1128/aac.30.6.913. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Decazes J. M., Ernst J. D., Sande M. A. Correlation of in vitro time-kill curves and kinetics of bacterial killing in cerebrospinal fluid during ceftriaxone therapy of experimental Escherichia coli meningitis. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1983 Oct;24(4):463–467. doi: 10.1128/aac.24.4.463. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drake T. A., Hackbarth C. J., Sande M. A. Value of serum tests in combined drug therapy of endocarditis. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1983 Nov;24(5):653–657. doi: 10.1128/aac.24.5.653. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gerber A. U., Feller-Segessenmann C. In-vivo assessment of in-vitro killing patterns of Pseudomonas aeruginosa. J Antimicrob Chemother. 1985 Jan;15 (Suppl A):201–206. doi: 10.1093/jac/15.suppl_a.201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Juvin M. E., Drugeon H. B., Caillon J., Pirault J. L. Comparaison de l'activité bactéricide de trois aminosides: gentamicine, tobramycine, amikacine. Pathol Biol (Paris) 1987 May;35(5):461–465. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klastersky J., Daneau D., Swings G., Weerts D. Antibacterial activity in serum and urine as a therapeutic guide in bacterial infections. J Infect Dis. 1974 Feb;129(2):187–193. doi: 10.1093/infdis/129.2.187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mouton Y., Beuscart C., Leroy O., Pappo M., Drugeon H. Etude prospective randomisée contrôlée de l'association ceftazidime-péfloxacine versus ceftazidime-amikacine dans le traitement empirique des pneumonies et septicémies nosocomiales de réanimation. Résultats préliminaires. Presse Med. 1988 Oct 26;17(37):1928–1932. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schentag J. J., Swanson D. J., Smith I. L. Dual individualization: antibiotic dosage calculation from the integration of in-vitro pharmacodynamics and in-vivo pharmacokinetics. J Antimicrob Chemother. 1985 Jan;15 (Suppl A):47–57. doi: 10.1093/jac/15.suppl_a.47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stamey T. A., Bragonje J. Resistance to nalidixic acid. A misconception due to underdosage. JAMA. 1976 Oct 18;236(16):1857–1860. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van der Auwera P., Klastersky J., Lieppe S., Husson M., Lauzon D., Lopez A. P. Bactericidal activity and killing rate of serum from volunteers receiving pefloxacin alone or in combination with amikacin. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1986 Feb;29(2):230–234. doi: 10.1128/aac.29.2.230. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vogelman B., Craig W. A. Kinetics of antimicrobial activity. J Pediatr. 1986 May;108(5 Pt 2):835–840. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3476(86)80754-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vogelman B., Gudmundsson S., Leggett J., Turnidge J., Ebert S., Craig W. A. Correlation of antimicrobial pharmacokinetic parameters with therapeutic efficacy in an animal model. J Infect Dis. 1988 Oct;158(4):831–847. doi: 10.1093/infdis/158.4.831. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]