Abstract

Aims: To determine bacterial loads in meningococcal disease (MCD), their relation with disease severity, and the factors which determine bacterial load.

Methods: Meningococcal DNA quantification was performed by the Taqman PCR method on admission and sequential blood samples from patients with MCD. Disease severity was assessed using the Glasgow Septicaemia Prognostic Score (GMSPS, range 0–15, severe disease ≥8).

Results: Median admission bacterial load was 1.6 x 106 DNA copies/ml of blood (range 2.2 x 104 to 1.6 x 108). Bacterial load was significantly higher in patients with severe (8.4 x 106) compared to milder disease (1.1 x 106, p = 0.018). This difference was greater in septicaemic patients (median 1.6 x 107 versus 9.2 x 105, p < 0.001). Bacterial loads were significantly higher in patients that died (p = 0.017). Admission bacterial load was independent of the duration of clinical symptoms prior to admission, with no difference between the duration of symptoms in mild or severe cases (median, 10.5 and 11 hours respectively). Bacterial loads were independent of DNA elimination rates following treatment.

Conclusion: Patients with MCD have higher bacterial loads than previously determined with quantitative culture methods. Admission bacterial load is significantly higher in patients with severe disease (GMSPS ≥8) and maximum load is highest in those who die. Bacterial load is independent of the duration of clinical symptoms or the decline in DNA load.

Full Text

The Full Text of this article is available as a PDF (95.5 KB).

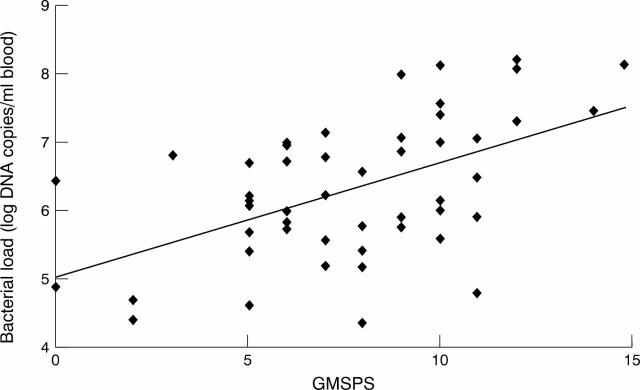

Figure 1 .

Correlation between admission bacterial loads and maximum GMSPS.

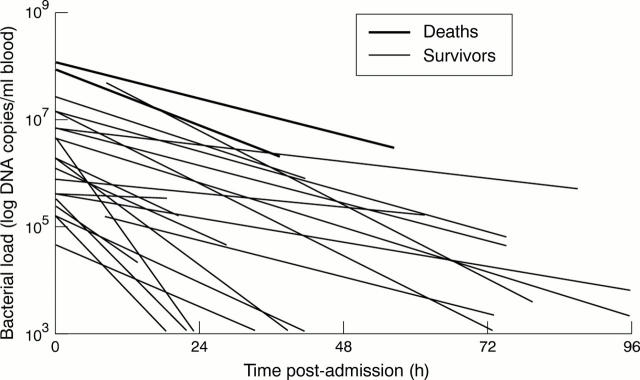

Figure 2 .

Linear regression analysis showing decline in bacterial DNA load from sequential EDTA samples.

Selected References

These references are in PubMed. This may not be the complete list of references from this article.

- Guiver M., Borrow R., Marsh J., Gray S. J., Kaczmarski E. B., Howells D., Boseley P., Fox A. J. Evaluation of the Applied Biosystems automated Taqman polymerase chain reaction system for the detection of meningococcal DNA. FEMS Immunol Med Microbiol. 2000 Jun;28(2):173–179. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-695X.2000.tb01473.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guiver M., Fox A. J., Mutton K., Mogulkoc N., Egan J. Evaluation of CMV viral load using TaqMan CMV quantitative PCR and comparison with CMV antigenemia in heart and lung transplant recipients. Transplantation. 2001 Jun 15;71(11):1609–1615. doi: 10.1097/00007890-200106150-00021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hart C. A., Cuevas L. E. Meningococcal disease in Africa. Ann Trop Med Parasitol. 1997 Oct;91(7):777–785. doi: 10.1080/00034989760536. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jefferies C., Lennon D., Stewart J., Martin D. Meningococcal disease in Auckland, July 1992 - June 1994. N Z Med J. 1999 Apr 9;112(1085):115–117. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Read R. C., Camp N. J., di Giovine F. S., Borrow R., Kaczmarski E. B., Chaudhary A. G., Fox A. J., Duff G. W. An interleukin-1 genotype is associated with fatal outcome of meningococcal disease. J Infect Dis. 2000 Oct 9;182(5):1557–1560. doi: 10.1086/315889. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sobanski M. A., Barnes R. A., Gray S. J., Carr A. D., Kaczmarski E. B., O'Rourke A., Murphy K., Cafferkey M., Ellis R. W., Pidcock K. Measurement of serum antigen concentration by ultrasound-enhanced immunoassay and correlation with clinical outcome in meningococcal disease. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. 2000 Apr;19(4):260–266. doi: 10.1007/s100960050473. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sullivan T. D., LaScolea L. J., Jr, Neter E. Relationship between the magnitude of bacteremia in children and the clinical disease. Pediatrics. 1982 Jun;69(6):699–702. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomson A. P., Sills J. A., Hart C. A. Validation of the Glasgow Meningococcal Septicemia Prognostic Score: a 10-year retrospective survey. Crit Care Med. 1991 Jan;19(1):26–30. doi: 10.1097/00003246-199101000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Uronen H., Williams A. J., Dixon G., Andersen S. R., Van Der Ley P., Van Deuren M., Callard R. E., Klein N. Gram-negative bacteria induce proinflammatory cytokine production by monocytes in the absence of lipopolysaccharide (LPS). Clin Exp Immunol. 2000 Dec;122(3):312–315. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2249.2000.01409.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Westendorp R. G., Hottenga J. J., Slagboom P. E. Variation in plasminogen-activator-inhibitor-1 gene and risk of meningococcal septic shock. Lancet. 1999 Aug 14;354(9178):561–563. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(98)09376-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Westendorp R. G., Langermans J. A., Huizinga T. W., Elouali A. H., Verweij C. L., Boomsma D. I., Vandenbroucke J. P., Vandenbrouke J. P. Genetic influence on cytokine production and fatal meningococcal disease. Lancet. 1997 Jan 18;349(9046):170–173. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(96)06413-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zwahlen A., Waldvogel F. A. Magnitude of bacteremia and complement activation during Neisseria meningitidis infection: study of two co-primary cases with different clinical presentations. Eur J Clin Microbiol. 1984 Oct;3(5):439–441. doi: 10.1007/BF02017367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Deuren M., van der Ven-Jongekrijg J., Bartelink A. K., van Dalen R., Sauerwein R. W., van der Meer J. W. Correlation between proinflammatory cytokines and antiinflammatory mediators and the severity of disease in meningococcal infections. J Infect Dis. 1995 Aug;172(2):433–439. doi: 10.1093/infdis/172.2.433. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]