Abstract

Background and aims: The incidence of complement abnormalities in the UK is not known. It is suggested in at least three major paediatric textbooks to test for abnormalities of the complement system following meningococcal disease (MCD).

Methods: Over a four year period, surviving children with a diagnosis of MCD had complement activity assessed. A total of 297 children, aged 2 months to 16 years were screened.

Results: All children except one had disease caused by B or C serogroups. One child, with group B meningococcal septicaemia (complicated by disseminated intravascular coagulation and who required ventilation and inotropic support) was complement deficient. C2 deficiency was subsequently diagnosed. She had other major pointers towards an immunological abnormality prior to her MCD.

Conclusion: It is unnecessary to screen all children routinely following MCD if caused by group B or C infection. However, it is important to assess the previous health of the child and to investigate appropriately if there have been previous suspicious infections, abnormal course of infective illnesses, or if this is a repeated episode of neisserial infection.

Full Text

The Full Text of this article is available as a PDF (84.3 KB).

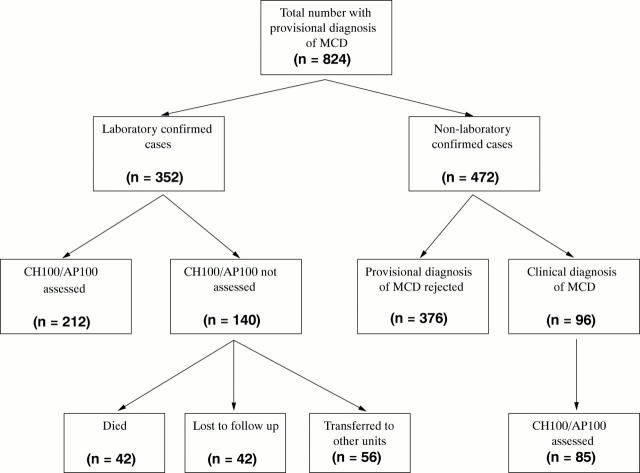

Figure 1 .

Breakdown of numbers of children with a provisional diagnosis of MCD who were then screened for abnormalities of the complement system. Only one of these children was complement deficient.

Selected References

These references are in PubMed. This may not be the complete list of references from this article.

- Derkx H. H., Kuijper E. J., Fijen C. A., Jak M., Dankert J., van Deventer S. J. Inherited complement deficiency in children surviving fulminant meningococcal septic shock. Eur J Pediatr. 1995 Sep;154(9):735–738. doi: 10.1007/BF02276718. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ellison R. T., 3rd, Kohler P. F., Curd J. G., Judson F. N., Reller L. B. Prevalence of congenital or acquired complement deficiency in patients with sporadic meningocococcal disease. N Engl J Med. 1983 Apr 21;308(16):913–916. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198304213081601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Figueroa J., Andreoni J., Densen P. Complement deficiency states and meningococcal disease. Immunol Res. 1993;12(3):295–311. doi: 10.1007/BF02918259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fijen C. A., Kuijper E. J., Hannema A. J., Sjöholm A. G., van Putten J. P. Complement deficiencies in patients over ten years old with meningococcal disease due to uncommon serogroups. Lancet. 1989 Sep 9;2(8663):585–588. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(89)90712-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fijen C. A., Kuijper E. J., Tjia H. G., Daha M. R., Dankert J. Complement deficiency predisposes for meningitis due to nongroupable meningococci and Neisseria-related bacteria. Clin Infect Dis. 1994 May;18(5):780–784. doi: 10.1093/clinids/18.5.780. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fijen C. A., Kuijper E. J., te Bulte M. T., Daha M. R., Dankert J. Assessment of complement deficiency in patients with meningococcal disease in The Netherlands. Clin Infect Dis. 1999 Jan;28(1):98–105. doi: 10.1086/515075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tedesco F., Nürnberger W., Perissutti S. Inherited deficiencies of the terminal complement components. Int Rev Immunol. 1993;10(1):51–64. doi: 10.3109/08830189309051171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Truedsson L., Sjöholm A. G., Laurell A. B. Screening for deficiencies in the classical and alternative pathways of complement by hemolysis in gel. Acta Pathol Microbiol Scand C. 1981 Jun;89(3):161–166. doi: 10.1111/j.1699-0463.1981.tb02680.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]