Abstract

Parental height is frequently treated as a biological variable in studies of birth weight and childhood growth. Elimination of social variables from multivariate models including parental height as a biological variable leads researchers to conclude that social factors have no independent effect on the outcome. This paper challenges the treatment of parental height as a biological variable, drawing on extensive evidence for the determination of adult height through a complex interaction of genetic and social factors. The paper firstly seeks to establish the importance of social factors in the determination of height. The methodological problems associated with treatment of parental height as a purely biological variable are then discussed, illustrated by data from published studies and by analysis of data from the 1958 National Childhood Development Study (NCDS). The paper concludes that a framework for studying pathways to pregnancy and childhood outcomes needs to take account of the complexity of the relation between genetic and social factors and be able to account for the effects of multiple risk factors acting cumulatively across time and across generations. Illustrations of these approaches are given using NCDS data.

Full Text

The Full Text of this article is available as a PDF (127.2 KB).

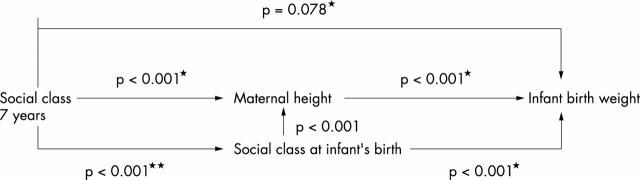

Figure 1 .

Preliminary path analysis from maternal social class at 7 years to infant's birth weight among 2922 NCDS cohort female members. *Linear regression model; **logistic regression model.

Selected References

These references are in PubMed. This may not be the complete list of references from this article.

- Alberman E., Filakti H., Williams S., Evans S. J., Emanuel I. Early influences on the secular change in adult height between the parents and children of the 1958 birth cohort. Ann Hum Biol. 1991 Mar-Apr;18(2):127–136. doi: 10.1080/03014469100001472. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arbuckle T. E., Sherman G. J. Comparison of the risk factors for pre-term delivery and intrauterine growth retardation. Paediatr Perinat Epidemiol. 1989 Apr;3(2):115–129. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3016.1989.tb00503.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brooke O. G., Anderson H. R., Bland J. M., Peacock J. L., Stewart C. M. Effects on birth weight of smoking, alcohol, caffeine, socioeconomic factors, and psychosocial stress. BMJ. 1989 Mar 25;298(6676):795–801. doi: 10.1136/bmj.298.6676.795. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Emanuel I., Filakti H., Alberman E., Evans S. J. Intergenerational studies of human birthweight from the 1958 birth cohort. 1. Evidence for a multigenerational effect. Br J Obstet Gynaecol. 1992 Jan;99(1):67–74. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-0528.1992.tb14396.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Golding J., Thomas P., Peters T. Does father's unemployment put the fetus at risk? Br J Obstet Gynaecol. 1986 Jul;93(7):704–710. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greulich W. W. Some secular changes in the growth of American-born and native Japanese children. Am J Phys Anthropol. 1976 Nov;45(3 Pt 2):553–568. doi: 10.1002/ajpa.1330450320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gulliford M. C., Chinn S., Rona R. J. Social environment and height: England and Scotland 1987 and 1988. Arch Dis Child. 1991 Feb;66(2):235–240. doi: 10.1136/adc.66.2.235. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harris B. Health, height, and history: an overview of recent developments in anthropometric history. Soc Hist Med. 1994 Aug;7(2):297–320. doi: 10.1093/shm/7.2.297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hennessy E., Alberman E. Intergenerational influences affecting birth outcome. I. Birthweight for gestational age in the children of the 1958 British birth cohort. Paediatr Perinat Epidemiol. 1998 Jul;12 (Suppl 1):45–60. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-3016.1998.0120s1045.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kiernan K. E. Who remains celibate? J Biosoc Sci. 1988 Jul;20(3):253–263. doi: 10.1017/s0021932000006593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Komlos J. Patterns of children's growth in east-central Europe in the eighteenth century. Ann Hum Biol. 1986 Jan-Feb;13(1):33–48. doi: 10.1080/03014468600008181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kramer M. S. Determinants of low birth weight: methodological assessment and meta-analysis. Bull World Health Organ. 1987;65(5):663–737. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kramer M. S., Goulet L., Lydon J., Séguin L., McNamara H., Dassa C., Platt R. W., Chen M. F., Gauthier H., Genest J. Socio-economic disparities in preterm birth: causal pathways and mechanisms. Paediatr Perinat Epidemiol. 2001 Jul;15 (Suppl 2):104–123. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-3016.2001.00012.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kramer M. S., Séguin L., Lydon J., Goulet L. Socio-economic disparities in pregnancy outcome: why do the poor fare so poorly? Paediatr Perinat Epidemiol. 2000 Jul;14(3):194–210. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-3016.2000.00266.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Logan S., Spencer N. Smoking and other health related behaviour in the social and environmental context. Arch Dis Child. 1996 Feb;74(2):176–179. doi: 10.1136/adc.74.2.176. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meis P. J., Michielutte R., Peters T. J., Wells H. B., Sands R. E., Coles E. C., Johns K. A. Factors associated with term low birthweight in Cardiff, Wales. Paediatr Perinat Epidemiol. 1997 Jul;11(3):287–297. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3016.1997.tb00006.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nordström M. L., Cnattingius S. Effects on birthweights of maternal education, socio-economic status, and work-related characteristics. Scand J Soc Med. 1996 Mar;24(1):55–61. doi: 10.1177/140349489602400109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reading R., Raybould S., Jarvis S. Deprivation, low birth weight, and children's height: a comparison between rural and urban areas. BMJ. 1993 Dec 4;307(6917):1458–1462. doi: 10.1136/bmj.307.6917.1458. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sheehan T. J. Stress and low birth weight: a structural modeling approach using real life stressors. Soc Sci Med. 1998 Nov;47(10):1503–1512. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(98)00236-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Susser M., Levin B. Ordeals for the fetal programming hypothesis. The hypothesis largely survives one ordeal but not another. BMJ. 1999 Apr 3;318(7188):885–886. doi: 10.1136/bmj.318.7188.885. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tuntiseranee P., Olsen J., Chongsuvivatwong V., Limbutara S. Socioeconomic and work related determinants of pregnancy outcome in southern Thailand. J Epidemiol Community Health. 1999 Oct;53(10):624–629. doi: 10.1136/jech.53.10.624. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Victora C. G., Huttly S. R., Barros F. C., Lombardi C., Vaughan J. P. Maternal education in relation to early and late child health outcomes: findings from a Brazilian cohort study. Soc Sci Med. 1992 Apr;34(8):899–905. doi: 10.1016/0277-9536(92)90258-r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whincup P. H., Cook D. G., Shaper A. G. Social class and height. BMJ. 1988 Oct 15;297(6654):980–981. doi: 10.1136/bmj.297.6654.980-c. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]