Full Text

The Full Text of this article is available as a PDF (163.8 KB).

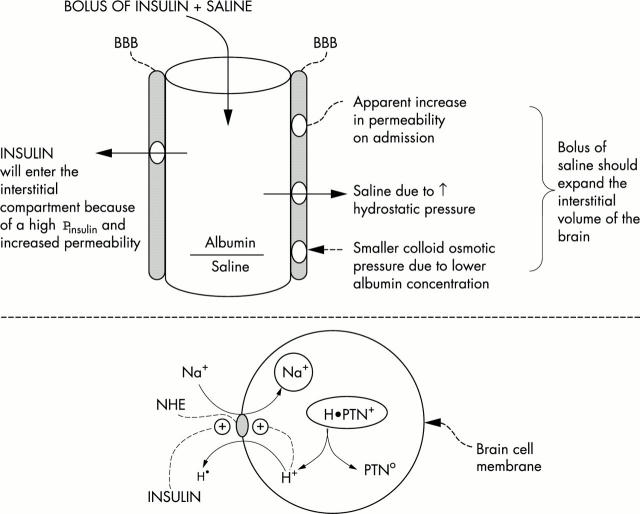

Figure 1 .

Early risk factors for the development of cerebral oedema. The top portion depicts the BBB that may be less restrictive early in therapy for DKA. Hence a bolus of saline could expand the intracranial interstitial volume. A bolus of insulin could expand the intracerebral ICF volume by converting the inactive form of NHE to its active form (bottom portion)—this causes Na+ to enter and H+ to exit from cells. One ultimate source of H+ in the ICF is from macromolecules (proteins designated H•PTN+). The net result is the electroneutral and stoichiometric exchange of cations (a gain of monovalent Na+ and the change in protein charge form a cationic to a less cationic form, depicted in the ICF ovals).

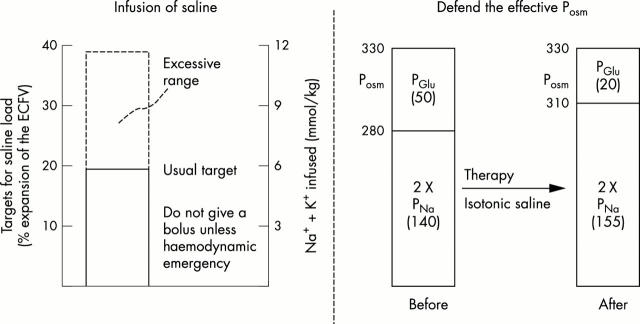

Figure 2 .

Late risk factors for the development of cerebral oedema. The risk associated with an infusion of too large a volume of saline (left portion) is expansion of the interstitial volume of the brain. If this occurs, the patient may develop an increased ICP even if there is a less severe degree of brain cell swelling. As shown in the right portion, a rise in PNa is needed to prevent a fall in the effective Posm when there is a fall in PGlu. The PNa must be >140 mmol/l if the PNa on admission is close to 140 mmol/l.

Selected References

These references are in PubMed. This may not be the complete list of references from this article.

- Danowski T. S., Peters J. H., Rathbun J. C., Quashnock J. M., Greenman L. STUDIES IN DIABETIC ACIDOSIS AND COMA, WITH PARTICULAR EMPHASIS ON THE RETENTION OF ADMINISTERED POTASSIUM. J Clin Invest. 1949 Jan;28(1):1–9. doi: 10.1172/JCI102037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davids M. R., Edoute Y., Stock S., Halperin M. L. Severe degree of hyperglycaemia: insights from integrative physiology. QJM. 2002 Feb;95(2):113–124. doi: 10.1093/qjmed/95.2.113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Durr J. A., Hoffman W. H., Sklar A. H., el Gammal T., Steinhart C. M. Correlates of brain edema in uncontrolled IDDM. Diabetes. 1992 May;41(5):627–632. doi: 10.2337/diab.41.5.627. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edge J. A. Cerebral oedema during treatment of diabetic ketoacidosis: are we any nearer finding a cause? Diabetes Metab Res Rev. 2000 Sep-Oct;16(5):316–324. doi: 10.1002/1520-7560(2000)9999:9999<::aid-dmrr143>3.0.co;2-r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Felner E. I., White P. C. Improving management of diabetic ketoacidosis in children. Pediatrics. 2001 Sep;108(3):735–740. doi: 10.1542/peds.108.3.735. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glaser N., Barnett P., McCaslin I., Nelson D., Trainor J., Louie J., Kaufman F., Quayle K., Roback M., Malley R. Risk factors for cerebral edema in children with diabetic ketoacidosis. The Pediatric Emergency Medicine Collaborative Research Committee of the American Academy of Pediatrics. N Engl J Med. 2001 Jan 25;344(4):264–269. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200101253440404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hale P. M., Rezvani I., Braunstein A. W., Lipman T. H., Martinez N., Garibaldi L. Factors predicting cerebral edema in young children with diabetic ketoacidosis and new onset type I diabetes. Acta Paediatr. 1997 Jun;86(6):626–631. doi: 10.1111/j.1651-2227.1997.tb08946.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harris G. D., Fiordalisi I., Harris W. L., Mosovich L. L., Finberg L. Minimizing the risk of brain herniation during treatment of diabetic ketoacidemia: a retrospective and prospective study. J Pediatr. 1990 Jul;117(1 Pt 1):22–31. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3476(05)82439-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoffman W. H., Steinhart C. M., el Gammal T., Steele S., Cuadrado A. R., Morse P. K. Cranial CT in children and adolescents with diabetic ketoacidosis. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 1988 Jul-Aug;9(4):733–739. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Inward C. D., Chambers T. L. Fluid management in diabetic ketoacidosis. Arch Dis Child. 2002 Jun;86(6):443–444. doi: 10.1136/adc.86.6.443. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Juel C., Halestrap A. P. Lactate transport in skeletal muscle - role and regulation of the monocarboxylate transporter. J Physiol. 1999 Jun 15;517(Pt 3):633–642. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.1999.0633s.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kamel K. S., Cheema-Dhadli S., Halperin F. A., Vasudevan S., Halperin M. L. Anion gap: may the anions restricted to the intravascular space undergo modification in their valence? Nephron. 1996;73(3):382–389. doi: 10.1159/000189097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krane E. J., Rockoff M. A., Wallman J. K., Wolfsdorf J. I. Subclinical brain swelling in children during treatment of diabetic ketoacidosis. N Engl J Med. 1985 May 2;312(18):1147–1151. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198505023121803. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mahoney C. A. Extreme gestational starvation ketoacidosis: case report and review of pathophysiology. Am J Kidney Dis. 1992 Sep;20(3):276–280. doi: 10.1016/s0272-6386(12)80701-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moore R. D. Stimulation of Na:H exchange by insulin. Biophys J. 1981 Feb;33(2):203–210. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(81)84881-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roscoe J. M., Halperin M. L., Rolleston F. S., Goldstein M. B. Hyperglycemia-induced hyponatremia: metabolic considerations in calculation of serum sodium depression. Can Med Assoc J. 1975 Feb 22;112(4):452–453. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosenbloom A. L. Intracerebral crises during treatment of diabetic ketoacidosis. Diabetes Care. 1990 Jan;13(1):22–33. doi: 10.2337/diacare.13.1.22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SWAN R. C., PITTS R. F. Neutralization of infused acid by nephrectomized dogs. J Clin Invest. 1955 Feb;34(2):205–212. doi: 10.1172/JCI103073. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soleimani M., Singh G. Physiologic and molecular aspects of the Na+/H+ exchangers in health and disease processes. J Investig Med. 1995 Oct;43(5):419–430. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van der Meulen J. A., Klip A., Grinstein S. Possible mechanism for cerebral oedema in diabetic ketoacidosis. Lancet. 1987 Aug 8;2(8554):306–308. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(87)90892-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vasuvattakul S., Warner L. C., Halperin M. L. Quantitative role of the intracellular bicarbonate buffer system in response to an acute acid load. Am J Physiol. 1992 Feb;262(2 Pt 2):R305–R309. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.1992.262.2.R305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yip C. C., Moule M. L., Yeung C. W. Characterization of insulin receptor subunits in brain and other tissues by photoaffinity labeling. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1980 Oct 31;96(4):1671–1678. doi: 10.1016/0006-291x(80)91366-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]