Abstract

Aims: Hypoalbuminaemia has significance in adult critical illness as an independent predictor of mortality. In addition, the anion gap is predominantly due to the negative charge of albumin, thus hypoalbuminaemia may lead to its underestimation. We examine this phenomenon in critically ill children, documenting the incidence, early evolution, and prognosis of hypoalbuminaemia (<33 g/l), and quantify its influence on the anion gap.

Methods: Prospective descriptive study of 134 critically ill children in the paediatric intensive care unit (ICU). Paired arterial blood samples were taken at ICU admission and 24 hours later, from which blood gases, electrolytes, and albumin were measured. The anion gap (including potassium) was calculated and then corrected for albumin using Figge's formula.

Results: The incidence of admission hypoalbuminaemia was 57%, increasing to 76% at 24 hours. Neither admission hypoalbuminaemia, nor extreme hypoalbuminaemia (<20 g/l) predicted mortality; however, there was an association with increased median ICU stay (4.9 v 3.6 days). After correction for albumin the incidence of a raised anion gap (>18 mEq/l) increased from 28% to 44% in all samples (n = 263); this discrepancy was more pronounced in the 103 samples with metabolic acidosis (38% v 73%). Correction produced an average increase in the anion gap of 2.7 mEq/l (mean bias), with limits of agreement of ±3.7 mEq/l.

Conclusion: Admission hypoalbuminaemia is common in critical illness, but is not an independent predictor of mortality. However, failure to correct the anion gap for albumin may underestimate the true anion gap, producing error in the interpretation of acid-base abnormalities. This may have treatment implications.

Full Text

The Full Text of this article is available as a PDF (175.1 KB).

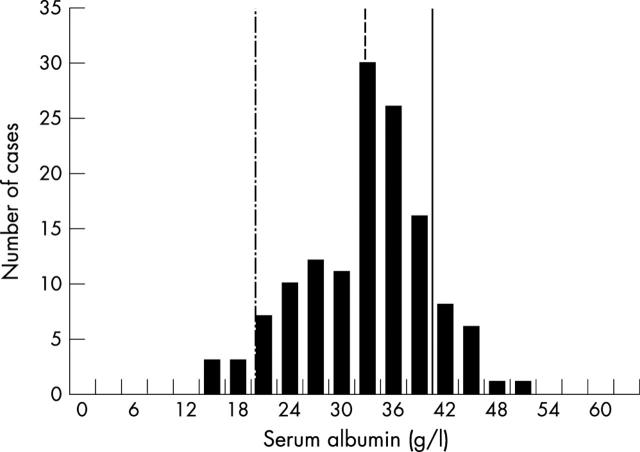

Figure 1.

Histogram of admission serum albumin concentration for all patients (n = 134). Lines indicate cut off values for normal albumin concentration (solid line), hypoalbuminaemia (dashed line), and extreme hypoalbuminaemia (dashed-dotted line).

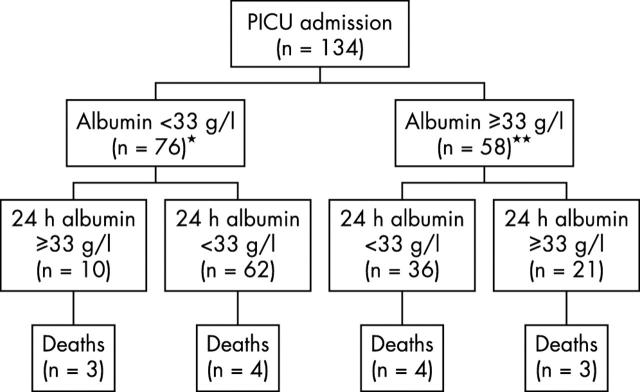

Figure 2.

Temporal profile of patients with (n = 76) and without admission hypoalbuminaemia (n = 58). *One death and three discharges from PICU before 24 hours; **one discharge from PICU before 24 hours.

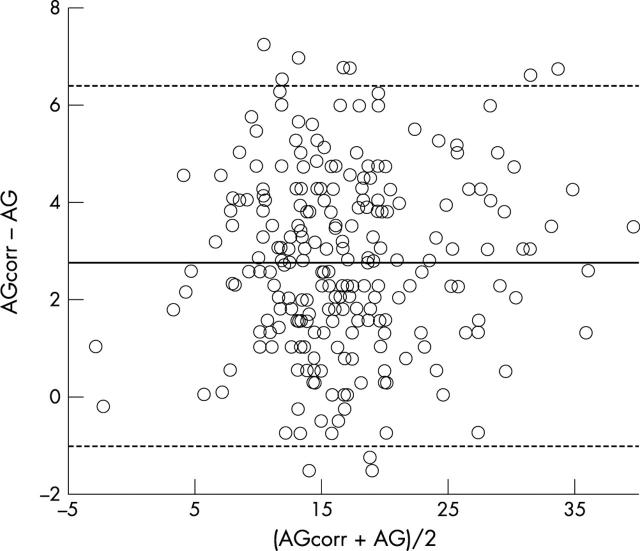

Figure 3.

Bland Altman plot for all samples (n = 263) comparing the corrected (AGcorr) and uncorrected anion gap (AG). Solid line represents the mean bias (2.7 mEq/l), dotted lines represent limits of agreement (-1.0 to 6.4 mEq/l).

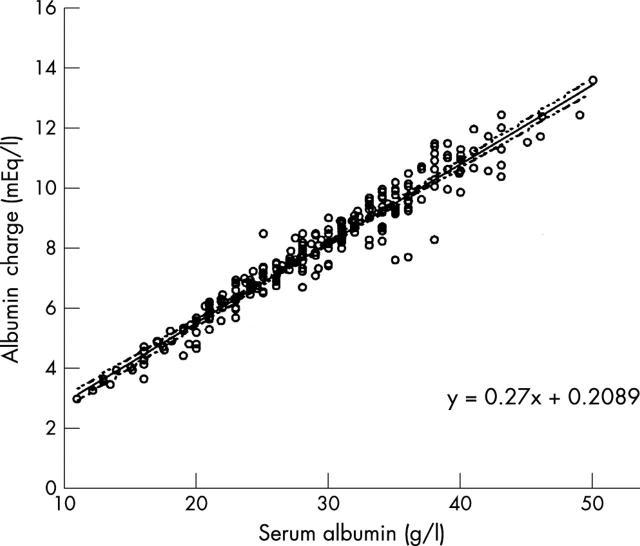

Figure 4.

Regression plot for the serum albumin concentration and albumin charge derived from Stewart's strong ion theory. The slope of the line is 0.27. Dotted lines represent 95% confidence intervals.

Selected References

These references are in PubMed. This may not be the complete list of references from this article.

- Blunt M. C., Nicholson J. P., Park G. R. Serum albumin and colloid osmotic pressure in survivors and nonsurvivors of prolonged critical illness. Anaesthesia. 1998 Aug;53(8):755–761. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2044.1998.00488.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cogo Paola E., Carnielli Virgilio P., Rosso Federica, Cesarone Arianna, Giordano Giuseppe, Faggian Diego, Plebani Mario, Barreca Antonina, Zacchello Franco. Protein turnover, lipolysis, and endogenous hormonal secretion in critically ill children. Crit Care Med. 2002 Jan;30(1):65–70. doi: 10.1097/00003246-200201000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Durward A., Skellett S., Mayer A., Taylor D., Tibby S. M., Murdoch I. A. The value of the chloride: sodium ratio in differentiating the aetiology of metabolic acidosis. Intensive Care Med. 2001 May;27(5):828–835. doi: 10.1007/s001340100915. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fencl V., Jabor A., Kazda A., Figge J. Diagnosis of metabolic acid-base disturbances in critically ill patients. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2000 Dec;162(6):2246–2251. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.162.6.9904099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Figge J., Jabor A., Kazda A., Fencl V. Anion gap and hypoalbuminemia. Crit Care Med. 1998 Nov;26(11):1807–1810. doi: 10.1097/00003246-199811000-00019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fleck A., Raines G., Hawker F., Trotter J., Wallace P. I., Ledingham I. M., Calman K. C. Increased vascular permeability: a major cause of hypoalbuminaemia in disease and injury. Lancet. 1985 Apr 6;1(8432):781–784. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(85)91447-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foley E. F., Borlase B. C., Dzik W. H., Bistrian B. R., Benotti P. N. Albumin supplementation in the critically ill. A prospective, randomized trial. Arch Surg. 1990 Jun;125(6):739–742. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.1990.01410180063012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Golub R., Sorrento J. J., Jr, Cantu R., Jr, Nierman D. M., Moideen A., Stein H. D. Efficacy of albumin supplementation in the surgical intensive care unit: a prospective, randomized study. Crit Care Med. 1994 Apr;22(4):613–619. doi: 10.1097/00003246-199404000-00017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hatherill M., Sajjanhar T., Tibby S. M., Champion M. P., Anderson D., Marsh M. J., Murdoch I. A. Serum lactate as a predictor of mortality after paediatric cardiac surgery. Arch Dis Child. 1997 Sep;77(3):235–238. doi: 10.1136/adc.77.3.235. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klonoff-Cohen H., Barrett-Connor E. L., Edelstein S. L. Albumin levels as a predictor of mortality in the healthy elderly. J Clin Epidemiol. 1992 Mar;45(3):207–212. doi: 10.1016/0895-4356(92)90080-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moomey C. B., Jr, Melton S. M., Croce M. A., Fabian T. C., Proctor K. G. Prognostic value of blood lactate, base deficit, and oxygen-derived variables in an LD50 model of penetrating trauma. Crit Care Med. 1999 Jan;27(1):154–161. doi: 10.1097/00003246-199901000-00044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nicholson J. P., Wolmarans M. R., Park G. R. The role of albumin in critical illness. Br J Anaesth. 2000 Oct;85(4):599–610. doi: 10.1093/bja/85.4.599. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rady M. Y., Ryan T. Perioperative predictors of extubation failure and the effect on clinical outcome after cardiac surgery. Crit Care Med. 1999 Feb;27(2):340–347. doi: 10.1097/00003246-199902000-00041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reilly R. F., Anderson R. J. Interpreting the anion gap. Crit Care Med. 1998 Nov;26(11):1771–1772. doi: 10.1097/00003246-199811000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reinhardt G. F., Myscofski J. W., Wilkens D. B., Dobrin P. B., Mangan J. E., Jr, Stannard R. T. Incidence and mortality of hypoalbuminemic patients in hospitalized veterans. JPEN J Parenter Enteral Nutr. 1980 Jul-Aug;4(4):357–359. doi: 10.1177/014860718000400404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shann F., Pearson G., Slater A., Wilkinson K. Paediatric index of mortality (PIM): a mortality prediction model for children in intensive care. Intensive Care Med. 1997 Feb;23(2):201–207. doi: 10.1007/s001340050317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stewart P. A. Independent and dependent variables of acid-base control. Respir Physiol. 1978 Apr;33(1):9–26. doi: 10.1016/0034-5687(78)90079-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stewart P. A. Modern quantitative acid-base chemistry. Can J Physiol Pharmacol. 1983 Dec;61(12):1444–1461. doi: 10.1139/y83-207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilkes P. Hypoproteinemia, strong-ion difference, and acid-base status in critically ill patients. J Appl Physiol (1985) 1998 May;84(5):1740–1748. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1998.84.5.1740. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]