Abstract

Background: The effects of maternal phenylalanine on the fetus include facial dysmorphism, microcephaly, intrauterine growth retardation, developmental delay, and congenital heart disease.

Aims: To evaluate the impact of phenylalanine restricted diet in pregnant women with phenylketonuria (PKU) on their offspring.

Methods: Data on virtually all pregnancies of women with PKU in the United Kingdom between 1978 and 1997 were reported to the United Kingdom PKU Registry. The effect of the use and timing in relation to pregnancy of a phenylalanine restricted diet on birth weight, birth head circumference, the presence or absence of congenital heart disease (CHD), 4 year developmental quotient, and 8 year intelligence quotient were examined.

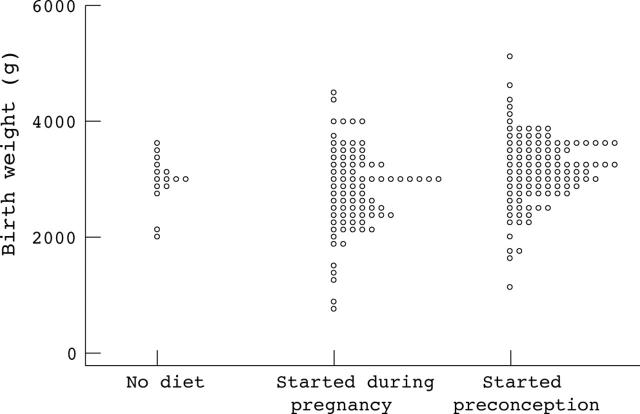

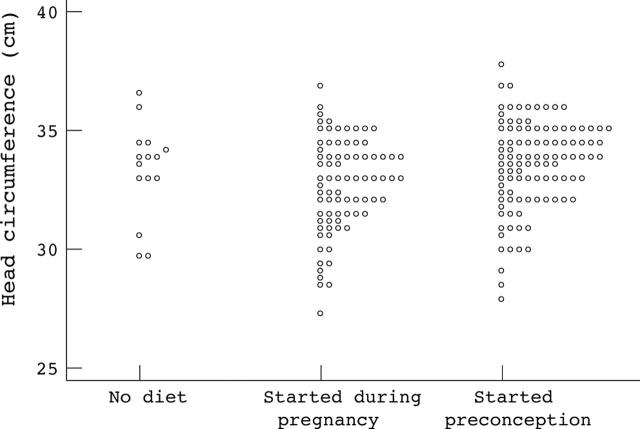

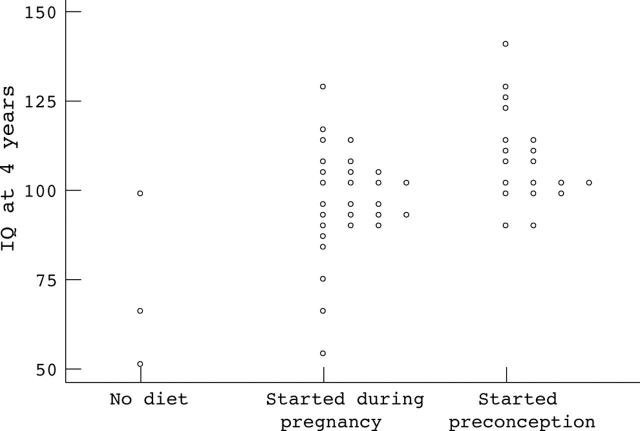

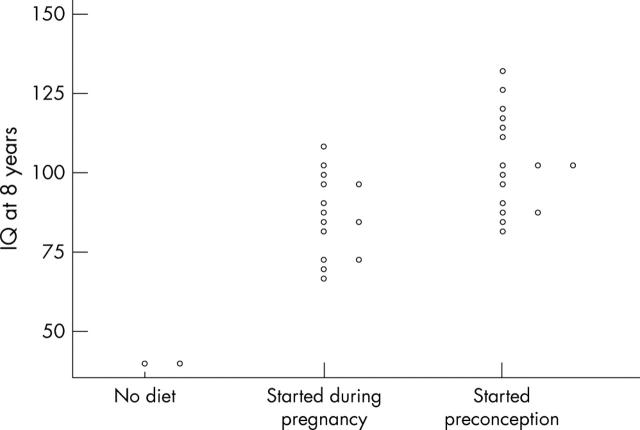

Results: A total of 228 pregnancies resulted in live births (seven twin pregnancies were excluded). In 110 (50%), diet started before conception. For this group mean (SD) birth weight was 3160 (612) g, birth head circumference 33.6 (1.9) cm, 4 year DQ 108.9 (13.2), 8 year IQ 103.4 (15.6), and incidence of CHD was 2.4%. In comparison, for those born where treatment was started during pregnancy (n = 91), birth weight was 2818 (711) g, birth head circumference 32.7 (2.0) cm, 4 year DQ 96.8 (15.0), 8 year IQ 86.5 (13.0), and incidence of CHD was 17%. Month-by-month regression analyses suggested that metabolic control by 12–16 weeks gestation had most influence on outcome.

Conclusions: Many features of the maternal PKU syndrome are preventable by starting a phenylalanine restricted diet. Women with PKU and their carers must be aware of the risks and should start the diet before conception, or as soon after as possible.

Full Text

The Full Text of this article is available as a PDF (88.5 KB).

Figure 1.

Birth weight of infants born to women with phenylketonuria according to timing of dietary intervention.

Figure 2.

Birth head circumference of infants born to women with phenylketonuria according to timing of dietary intervention.

Figure 3.

McCarthy Developmental Quotients at 4 years in infants born to women with phenylketonuria according to timing of dietary intervention.

Figure 4.

WISC-R Intelligence Quotients at 8 years in infants born to women with phenylketonuria according to timing of dietary intervention.

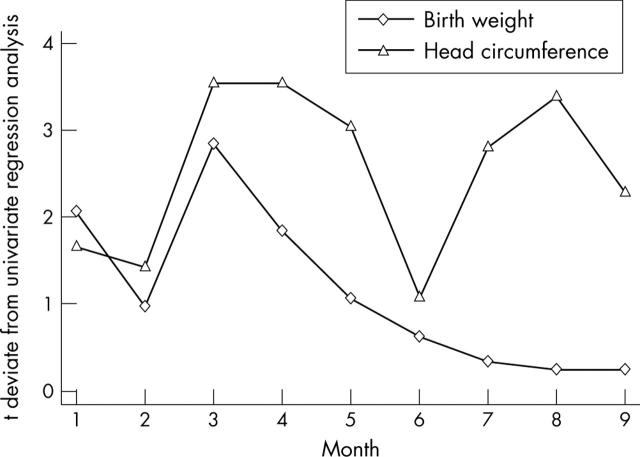

Figure 5.

t deviate values for birth weight and birth head circumference analysed month-by-month for infants born to women with phenylketonuria.

Selected References

These references are in PubMed. This may not be the complete list of references from this article.

- Burgard P., Bremer H. J., Bührdel P., Clemens P. C., Mönch E., Przyrembel H., Trefz F. K., Ullrich K. Rationale for the German recommendations for phenylalanine level control in phenylketonuria 1997. Eur J Pediatr. 1999 Jan;158(1):46–54. doi: 10.1007/s004310051008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- From the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Barriers to dietary control among pregnant women with phenylketonuria--United States, 1998-2000. JAMA. 2002 Mar 13;287(10):1258–1259. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- GUTHRIE R., SUSI A. A SIMPLE PHENYLALANINE METHOD FOR DETECTING PHENYLKETONURIA IN LARGE POPULATIONS OF NEWBORN INFANTS. Pediatrics. 1963 Sep;32:338–343. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koch R., Friedman E., Azen C., Hanley W., Levy H., Matalon R., Rouse B., Trefz F., Waisbren S., Michals-Matalon K. The International Collaborative Study of Maternal Phenylketonuria: status report 1998. Eur J Pediatr. 2000 Oct;159 (Suppl 2):S156–S160. doi: 10.1007/pl00014383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koch Richard, Hanley William, Levy Harvey, Matalon Kim, Matalon Reuben, Rouse Bobbye, Trefz Frederick, Güttler Flemming, Azen Colleen, Platt Larry. The Maternal Phenylketonuria International Study: 1984-2002. Pediatrics. 2003 Dec;112(6 Pt 2):1523–1529. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee P. J. Comments on the International Collaborative Study of Maternal Phenylketonuria: status report 1998. Eur J Pediatr. 2000 Oct;159 (Suppl 2):S161–S162. doi: 10.1007/pl00014384. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacDonald A., Rylance G. W., Asplin D., Hall S. K., Booth I. W. Does a single plasma phenylalanine predict quality of control in phenylketonuria? Arch Dis Child. 1998 Feb;78(2):122–126. doi: 10.1136/adc.78.2.122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith I., Glossop J., Beasley M. Fetal damage due to maternal phenylketonuria: effects of dietary treatment and maternal phenylalanine concentrations around the time of conception (an interim report from the UK Phenylketonuria Register). J Inherit Metab Dis. 1990;13(4):651–657. doi: 10.1007/BF01799520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Surtees R., Blau N. The neurochemistry of phenylketonuria. Eur J Pediatr. 2000 Oct;159 (Suppl 2):S109–S113. doi: 10.1007/pl00014370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]