Abstract

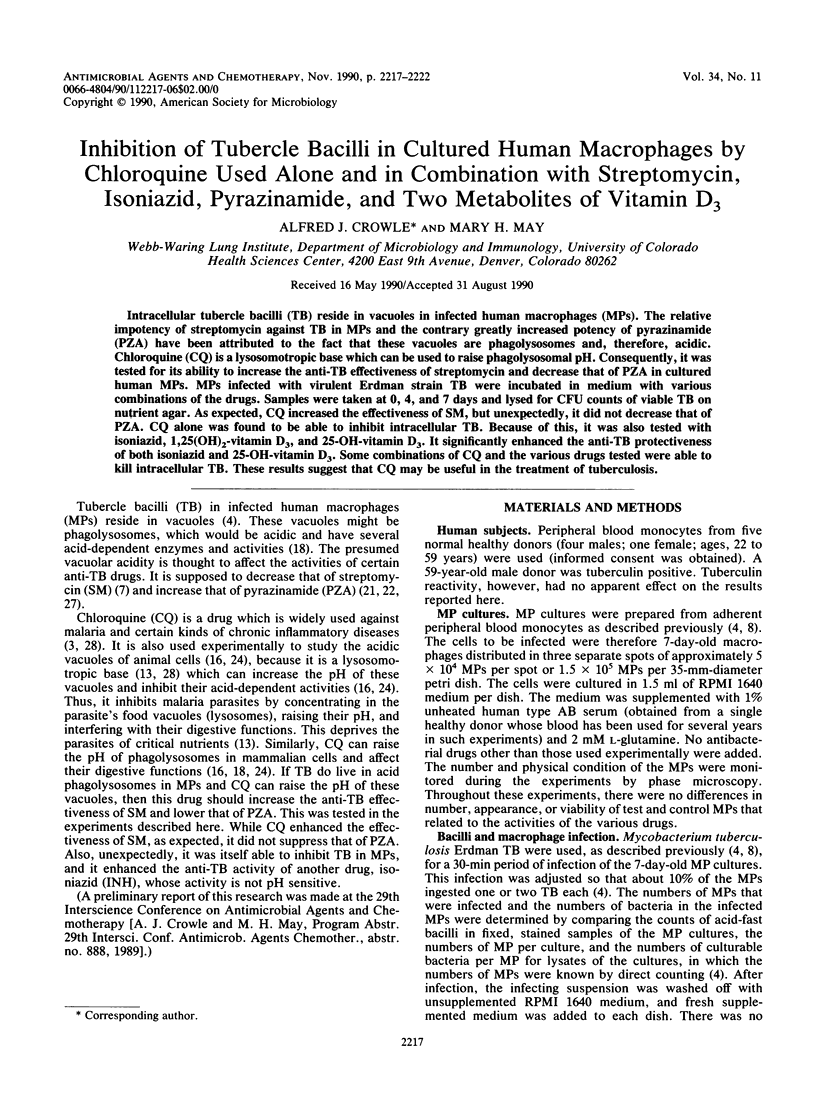

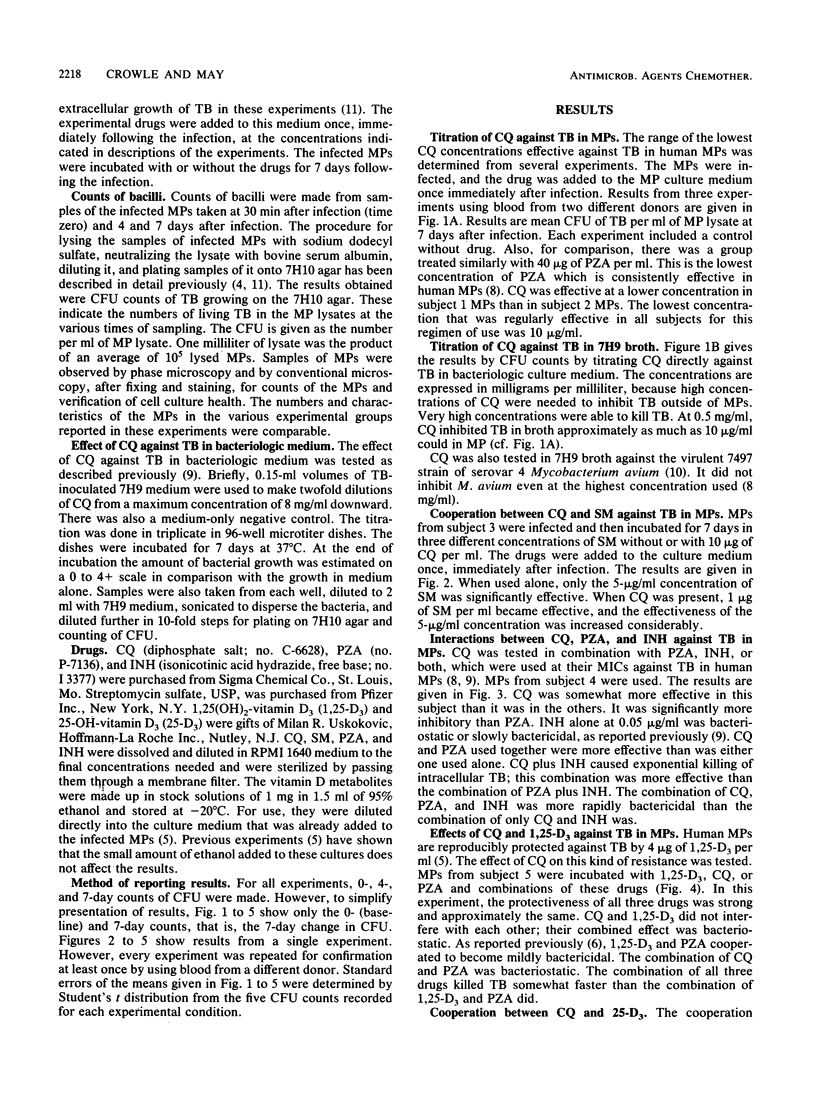

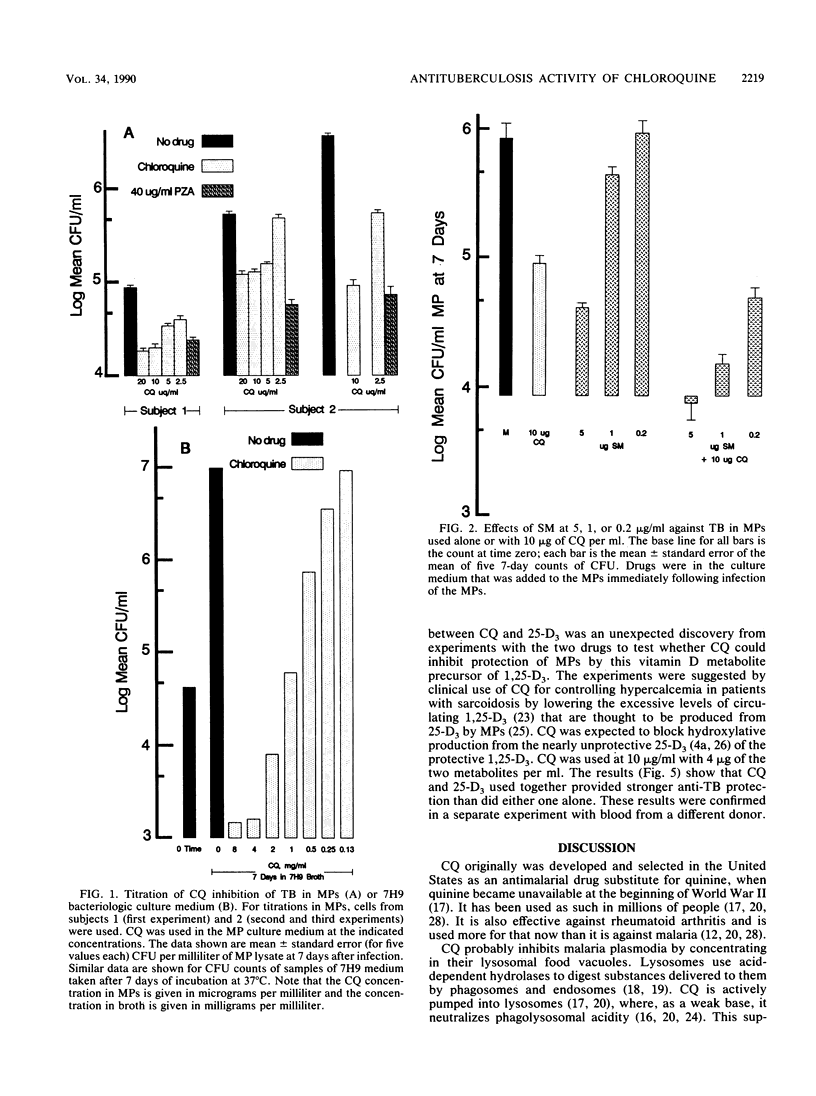

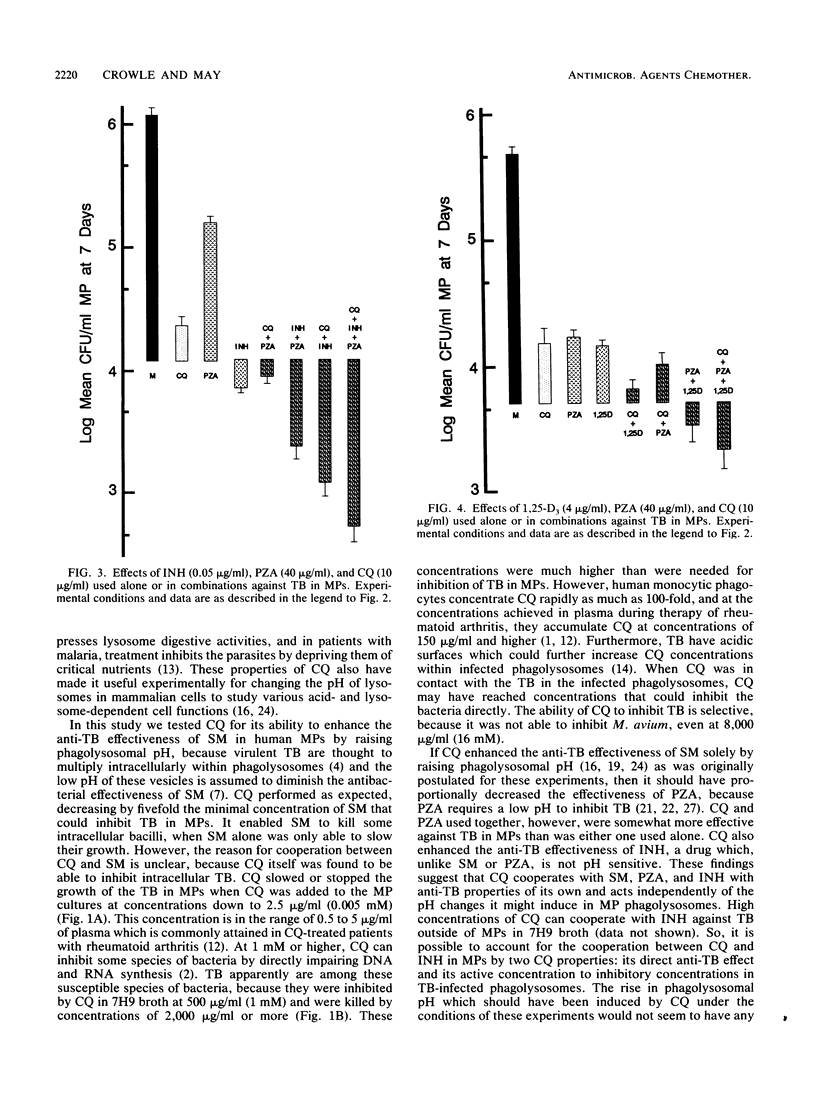

Intracellular tubercle bacilli (TB) reside in vacuoles in infected human macrophages (MPs). The relative impotency of streptomycin against TB in MPs and the contrary greatly increased potency of pyrazinamide (PZA) have been attributed to the fact that these vacuoles are phagolysosomes and, therefore, acidic. Chloroquine (CQ) is a lysomotropic base which can be used to raise phagolysosomal pH. Consequently, it was tested for its ability to increase the anti-TB effectiveness of streptomycin and decrease that of PZA in cultured human MPs. MPs infected with virulent Erdman strain TB were incubated in medium with various combinations of the drugs. Samples were taken at 0, 4, and 7 days and lysed for CFU counts of viable TB on nutrient agar. As expected, CQ increased the effectiveness of SM, but unexpectedly, it did not decrease that of PZA. CQ alone was found to be able to inhibit intracellular TB. Because of this, it was also tested with isoniazid, 1,25(OH)2-vitamin D3, and 25-OH-vitamin D3. It significantly enhanced the anti-TB protectiveness of both isoniazid and 25-OH-vitamin D3. Some combinations of CQ and the various drugs tested were able to kill intracellular TB. These results suggest that CQ may be useful in the treatment of tuberculosis.

Full text

PDF

Selected References

These references are in PubMed. This may not be the complete list of references from this article.

- Adelusi S. A., Salako L. A. Protein binding of chloroquine in the presence of aspirin. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 1982 Mar;13(3):451–452. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2125.1982.tb01402.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- COATNEY G. R. Pitfalls in a discovery: the chronicle of chloroquine. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 1963 Mar;12:121–128. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.1963.12.121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ciak J., Hahn F. E. Chloroquine: mode of action. Science. 1966 Jan 21;151(3708):347–349. doi: 10.1126/science.151.3708.347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crowle A. J., Ross E. J. Comparative abilities of various metabolites of vitamin D to protect cultured human macrophages against tubercle bacilli. J Leukoc Biol. 1990 Jun;47(6):545–550. doi: 10.1002/jlb.47.6.545. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crowle A. J., Ross E. J., May M. H. Inhibition by 1,25(OH)2-vitamin D3 of the multiplication of virulent tubercle bacilli in cultured human macrophages. Infect Immun. 1987 Dec;55(12):2945–2950. doi: 10.1128/iai.55.12.2945-2950.1987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crowle A. J., Salfinger M., May M. H. 1,25(OH)2-vitamin D3 synergizes with pyrazinamide to kill tubercle bacilli in cultured human macrophages. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1989 Feb;139(2):549–552. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm/139.2.549. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crowle A. J., Sbarbaro J. A., Judson F. N., Douvas G. S., May M. H. Inhibition by streptomycin of tubercle bacilli within cultured human macrophages. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1984 Nov;130(5):839–844. doi: 10.1164/arrd.1984.130.5.839. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crowle A. J., Sbarbaro J. A., May M. H. Effects of isoniazid and of ceforanide against virulent tubercle bacilli in cultured human macrophages. Tubercle. 1988 Mar;69(1):15–25. doi: 10.1016/0041-3879(88)90036-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crowle A. J., Sbarbaro J. A., May M. H. Inhibition by pyrazinamide of tubercle bacilli within cultured human macrophages. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1986 Nov;134(5):1052–1055. doi: 10.1164/arrd.1986.134.5.1052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crowle A. J., Tsang A. Y., Vatter A. E., May M. H. Comparison of 15 laboratory and patient-derived strains of Mycobacterium avium for ability to infect and multiply in cultured human macrophages. J Clin Microbiol. 1986 Nov;24(5):812–821. doi: 10.1128/jcm.24.5.812-821.1986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- French J. K., Hurst N. P., O'Donnell M. L., Betts W. H. Uptake of chloroquine and hydroxychloroquine by human blood leucocytes in vitro: relation to cellular concentrations during antirheumatic therapy. Ann Rheum Dis. 1987 Jan;46(1):42–45. doi: 10.1136/ard.46.1.42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geary T. G., Jensen J. B., Ginsburg H. Uptake of [3H]chloroquine by drug-sensitive and -resistant strains of the human malaria parasite Plasmodium falciparum. Biochem Pharmacol. 1986 Nov 1;35(21):3805–3812. doi: 10.1016/0006-2952(86)90668-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hart P. D., Young M. R., Gordon A. H., Sullivan K. H. Inhibition of phagosome-lysosome fusion in macrophages by certain mycobacteria can be explained by inhibition of lysosomal movements observed after phagocytosis. J Exp Med. 1987 Oct 1;166(4):933–946. doi: 10.1084/jem.166.4.933. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jensen P. E. Protein synthesis in antigen processing. J Immunol. 1988 Oct 15;141(8):2545–2550. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knox J. M., Owens D. W. The chloroquine mystery. Arch Dermatol. 1966 Aug;94(2):205–214. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kornfeld S. Trafficking of lysosomal enzymes. FASEB J. 1987 Dec;1(6):462–468. doi: 10.1096/fasebj.1.6.3315809. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krogstad D. J., Schlesinger P. H. Acid-vesicle function, intracellular pathogens, and the action of chloroquine against Plasmodium falciparum. N Engl J Med. 1987 Aug 27;317(9):542–549. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198708273170905. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mackenzie A. H. Pharmacologic actions of 4-aminoquinoline compounds. Am J Med. 1983 Jul 18;75(1A):5–10. doi: 10.1016/0002-9343(83)91264-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McDERMOTT W., TOMPSETT R. Activation of pyrazinamide and nicotinamide in acidic environments in vitro. Am Rev Tuberc. 1954 Oct;70(4):748–754. doi: 10.1164/art.1954.70.4.748. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mitchison D. A. The action of antituberculosis drugs in short-course chemotherapy. Tubercle. 1985 Sep;66(3):219–225. doi: 10.1016/0041-3879(85)90040-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O'Leary T. J., Jones G., Yip A., Lohnes D., Cohanim M., Yendt E. R. The effects of chloroquine on serum 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D and calcium metabolism in sarcoidosis. N Engl J Med. 1986 Sep 18;315(12):727–730. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198609183151203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poole B., Ohkuma S. Effect of weak bases on the intralysosomal pH in mouse peritoneal macrophages. J Cell Biol. 1981 Sep;90(3):665–669. doi: 10.1083/jcb.90.3.665. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reichel H., Koeffler H. P., Bishop J. E., Norman A. W. 25-Hydroxyvitamin D3 metabolism by lipopolysaccharide-stimulated normal human macrophages. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1987 Jan;64(1):1–9. doi: 10.1210/jcem-64-1-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rook G. A., Steele J., Fraher L., Barker S., Karmali R., O'Riordan J., Stanford J. Vitamin D3, gamma interferon, and control of proliferation of Mycobacterium tuberculosis by human monocytes. Immunology. 1986 Jan;57(1):159–163. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steele M. A., Des Prez R. M. The role of pyrazinamide in tuberculosis chemotherapy. Chest. 1988 Oct;94(4):845–850. doi: 10.1378/chest.94.4.845. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Titus E. O. Recent developments in the understanding of the pharmacokinetics and mechanism of action of chloroquine. Ther Drug Monit. 1989;11(4):369–379. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Webb A. R., Holick M. F. The role of sunlight in the cutaneous production of vitamin D3. Annu Rev Nutr. 1988;8:375–399. doi: 10.1146/annurev.nu.08.070188.002111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]