Abstract

AIM—To investigate the relation between common acid-base parameters and blood lactate concentrations and their prognostic importance in sick, ventilated neonates. METHODS—Two hundred and seventy eight serial simultaneous measurements of arterial acid-base status and blood lactate concentrations were carried out in 75 mechanically ventilated neonates with indwelling arterial catheters (gestational age and birthweight, median (range) - 29 (23-40) weeks, and 1340 (550-4080) g, respectively). RESULTS—There were no correlations between arterial blood lactate and pH and base excess within subjects (r=0.07 and r= -0.06, respectively) and only weakly positive but clinically irrelevant positive correlations between subjects (r=0.28 and r=0.27) in this group. Even in those infants who had not received any bicarbonate before their initial measurements (n=48), there were no correlations between initial blood lactate concentrations and pH (r=0.27), base excess (r=0.17), or serum bicarbonate concentrations (r=-0.18). There was no relation between peak lactate concentration (PLC) and base excess (r=0.16), and only a weak correlation between peak lactate concentration (PLC) and pH (r=0.28). Negative base excess was an insensitive indicator of raised lactate concentrations. Only two out of 33 (6%) instances of hyperlactataemia (lactate >2.5 mmol/l) would have been identified with a base excess <-10 mmol/l as a cutoff. Lower cutoff values of base excess or pH performed no better. Raised lactate concentrations were associated with increased mortality at all levels. While six of 53 (11%) infants with a PLC <2.5 mmol/l died, this proportion increased to four of 15 (27%) with a PLC between 2.5-5.0 mmol/l, and four of seven (57%) with a PLC >5.0 mmol/l. Infants showing little rise or a substantial fall in blood lactate fared better than those with persistently raised values. A clinically important increase in blood lactate preceded the development of clinical markers of deterioration and complications in six infants. CONCLUSIONS—Contrary to popular belief, pH or base excess cannot be used as proxy measures for blood lactate concentration, and independent measurements of the latter are needed. Blood lactate concentrations may provide an early warning signal and important prognostic information in ill, ventilated neonates. In this regard, serial measurements of blood lactate are more useful than a single value. Keywords: blood lactate; base excess; pH; neonatal intensive care.

Full Text

The Full Text of this article is available as a PDF (150.6 KB).

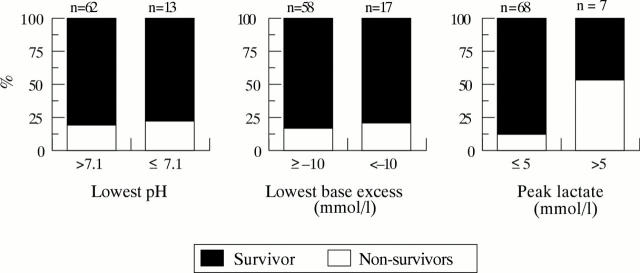

Figure 1 .

Correlations of arterial blood pH and base excess with blood lactate concentrations

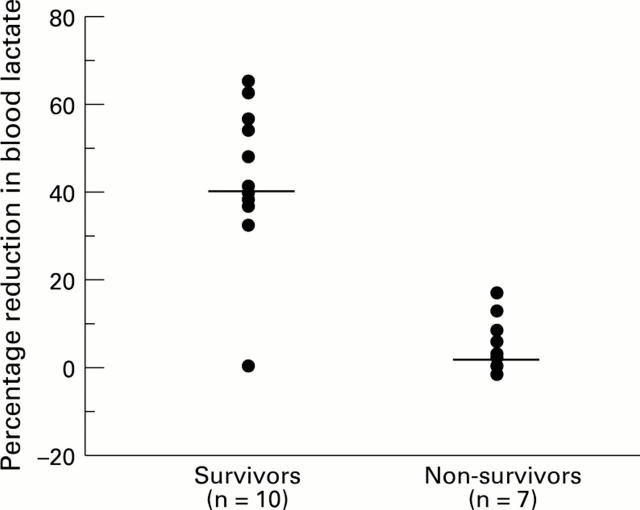

Figure 2 .

Inpatient mortality in relation to the lowest pH (7.1; P*=0.716), worst base excess (-10 mmol/l; P*=0.734), and peak blood lactate concentrations (5 mmol/l; P*=0.026) * Fisher's exact test

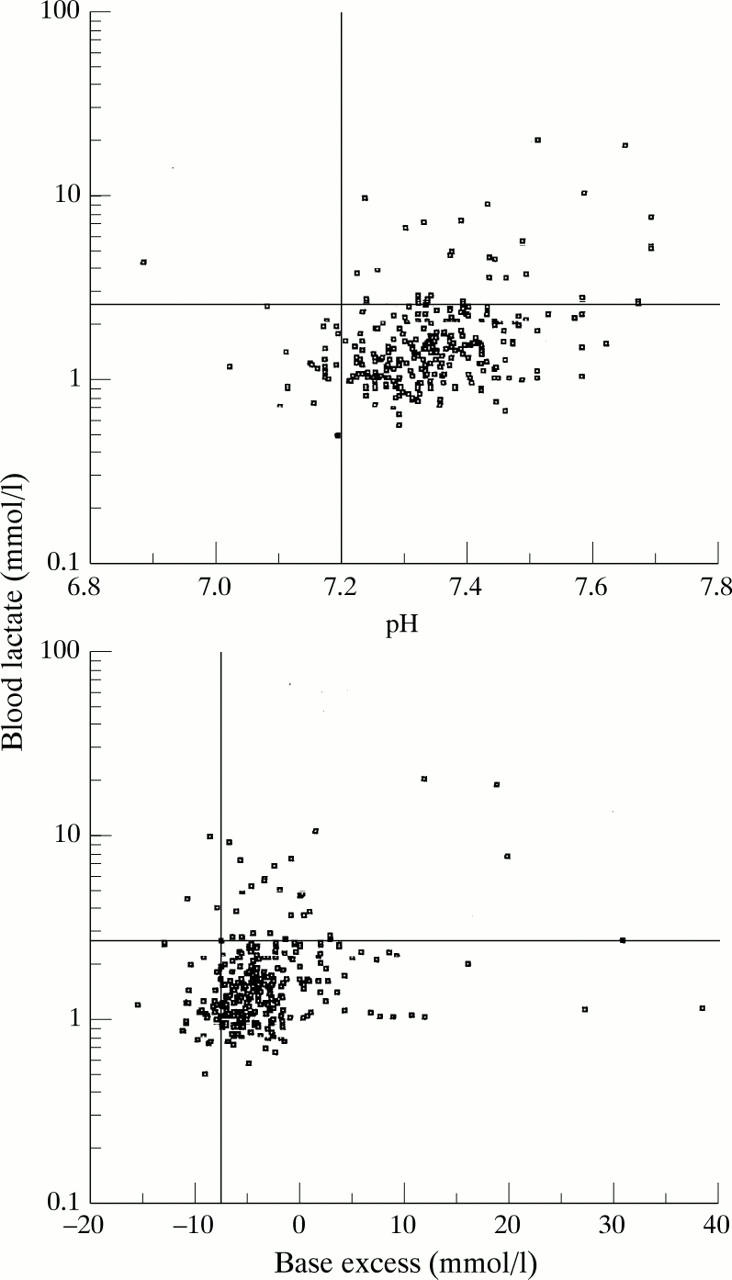

Figure 3 .

Per cent reduction in blood lactate concentrations in survivors and non-survivors after becoming hyperlactataemic ( blood lactate > 2.5 mmol/l) Median value for each group shown. Mann-Whitney U test showed that the two groups were significantly different from each other (P=0.008).

Selected References

These references are in PubMed. This may not be the complete list of references from this article.

- Adams J., 2nd, Hazard P. Comparison of blood lactate concentrations in arterial and peripheral venous blood. Crit Care Med. 1988 Sep;16(9):913–914. doi: 10.1097/00003246-198809000-00021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aduen J., Bernstein W. K., Khastgir T., Miller J., Kerzner R., Bhatiani A., Lustgarten J., Bassin A. S., Davison L., Chernow B. The use and clinical importance of a substrate-specific electrode for rapid determination of blood lactate concentrations. JAMA. 1994 Dec 7;272(21):1678–1685. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aduen J., Bernstein W. K., Miller J., Kerzner R., Bhatiani A., Davison L., Chernow B. Relationship between blood lactate concentrations and ionized calcium, glucose, and acid-base status in critically ill and noncritically ill patients. Crit Care Med. 1995 Feb;23(2):246–252. doi: 10.1097/00003246-199502000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alberti K. G., Cuthbert C. The hydrogen ion in normal metabolism: a review. Ciba Found Symp. 1982;87:1–19. doi: 10.1002/9780470720691.ch1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BRODER G., WEIL M. H. EXCESS LACTATE: AN INDEX OF REVERSIBILITY OF SHOCK IN HUMAN PATIENTS. Science. 1964 Mar 27;143(3613):1457–1459. doi: 10.1126/science.143.3613.1457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beca J. P., Scopes J. W. Serial determinations of blood lactate in respiratory distress syndrome. Arch Dis Child. 1972 Aug;47(254):550–557. doi: 10.1136/adc.47.254.550. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cady L. D., Jr, Weil M. H., Afifi A. A., Michaels S. F., Liu V. Y., Shubin H. Quantitation of severity of critical illness with special reference to blood lactate. Crit Care Med. 1973 Mar-Apr;1(2):75–80. doi: 10.1097/00003246-197303000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheung P. Y., Finer N. N. Plasma lactate concentration as a predictor of death in neonates with severe hypoxemia requiring extracorporeal membrane oxygenation. J Pediatr. 1994 Nov;125(5 Pt 1):763–768. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3476(94)70076-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheung P. Y., Robertson C. M., Finer N. N. Plasma lactate as a predictor of early childhood neurodevelopmental outcome of neonates with severe hypoxaemia requiring extracorporeal membrane oxygenation. Arch Dis Child Fetal Neonatal Ed. 1996 Jan;74(1):F47–F50. doi: 10.1136/fn.74.1.f47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fitzgerald M. J., Goto M., Myers T. F., Zeller W. P. Early metabolic effects of sepsis in the preterm infant: lactic acidosis and increased glucose requirement. J Pediatr. 1992 Dec;121(6):951–955. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3476(05)80350-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Graven S. N., Criscuolo D., Holcomb T. M. Blood lactate in the respiratory distress syndrome: significance in prognosis. Am J Dis Child. 1965 Dec;110(6):614–617. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.1965.02090030642004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gutierrez G., Hurtado F. J., Gutierrez A. M., Fernandez E. Net uptake of lactate by rabbit hindlimb during hypoxia. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1993 Nov;148(5):1204–1209. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm/148.5.1204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hawdon J. M., Ward Platt M. P., Aynsley-Green A. Patterns of metabolic adaptation for preterm and term infants in the first neonatal week. Arch Dis Child. 1992 Apr;67(4 Spec No):357–365. doi: 10.1136/adc.67.4_spec_no.357. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Izraeli S., Ben-Sira L., Harell D., Naor N., Ballin A., Davidson S. Lactic acid as a predictor for erythrocyte transfusion in healthy preterm infants with anemia of prematurity. J Pediatr. 1993 Apr;122(4):629–631. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3476(05)83551-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koch G., Wendel H. Adjustment of arterial blood gases and acid base balance in the normal newborn infant during the first week of life. Biol Neonat. 1968;12(3):136–161. doi: 10.1159/000240100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kruse J. A., Zaidi S. A., Carlson R. W. Significance of blood lactate levels in critically ill patients with liver disease. Am J Med. 1987 Jul;83(1):77–82. doi: 10.1016/0002-9343(87)90500-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mainwood G. W., Worsley-Brown P. The effects of extracellular pH and buffer concentration on the efflux of lactate from frog sartorius muscle. J Physiol. 1975 Aug;250(1):1–22. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1975.sp011040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mecher C., Rackow E. C., Astiz M. E., Weil M. H. Unaccounted for anion in metabolic acidosis during severe sepsis in humans. Crit Care Med. 1991 May;19(5):705–711. doi: 10.1097/00003246-199105000-00018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mizock B. A., Falk J. L. Lactic acidosis in critical illness. Crit Care Med. 1992 Jan;20(1):80–93. doi: 10.1097/00003246-199201000-00020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murdoch I. A., Turner C., Dalton R. N. Arterial or mixed venous lactate measurement in critically ill children. Is there a difference? Acta Paediatr. 1994 Apr;83(4):412–413. doi: 10.1111/j.1651-2227.1994.tb18131.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nielsen J., Ytrebø L. M., Borud O. Lactate and pyruvate concentrations in capillary blood from newborns. Acta Paediatr. 1994 Sep;83(9):920–922. doi: 10.1111/j.1651-2227.1994.tb13171.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nimmo G. R., Grant I. S., Mackenzie S. J. Lactate and acid base changes in the critically ill. Postgrad Med J. 1991;67 (Suppl 1):S56–S61. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peretz D. I., Scott H. M., Duff J., Dossetor J. B., MacLean L. D., McGregor M. The significance of lacticacidemia in the shock syndrome. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 1965 Jul 31;119(3):1133–1141. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1965.tb47467.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rashkin M. C., Bosken C., Baughman R. P. Oxygen delivery in critically ill patients. Relationship to blood lactate and survival. Chest. 1985 May;87(5):580–584. doi: 10.1378/chest.87.5.580. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Record C. O., Iles R. A., Cohen R. D., Williams R. Acid-base and metabolic disturbances in fulminant hepatic failure. Gut. 1975 Feb;16(2):144–149. doi: 10.1136/gut.16.2.144. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Relman A. S. Metabolic consequences of acid-base disorders. Kidney Int. 1972 May;1(5):347–359. doi: 10.1038/ki.1972.46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rose J. E., Hickman C. S. Citric acid aerosol as a potential smoking cessation aid. Chest. 1987 Dec;92(6):1005–1008. doi: 10.1378/chest.92.6.1005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sestoft L., Bartels P. D. Biochemistry and differential diagnosis of metabolic acidoses. Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1983 Jul;12(2):287–302. doi: 10.1016/s0300-595x(83)80042-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ui M. A role of phosphofructokinase in pH-dependent regulation of glycolysis. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1966 Aug 24;124(2):310–322. doi: 10.1016/0304-4165(66)90194-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Biervliet J. P., Van Stekelenburg G. J., Duran M., Wadman S. K. Letter: Base excess and organic acidaemia. Lancet. 1974 Dec 21;2(7895):1518–1519. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(74)90260-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vincent J. L., Dufaye P., Berré J., Leeman M., Degaute J. P., Kahn R. J. Serial lactate determinations during circulatory shock. Crit Care Med. 1983 Jun;11(6):449–451. doi: 10.1097/00003246-198306000-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weil M. H., Afifi A. A. Experimental and clinical studies on lactate and pyruvate as indicators of the severity of acute circulatory failure (shock). Circulation. 1970 Jun;41(6):989–1001. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.41.6.989. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weil M. H., Michaels S., Rackow E. C. Comparison of blood lactate concentrations in central venous, pulmonary artery, and arterial blood. Crit Care Med. 1987 May;15(5):489–490. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu J., Payne W. W., Ifekwunigwe A., Stevens J. Biochemical status of healthy premature infants in the first 48 hours of life. Arch Dis Child. 1965 Oct;40(213):516–525. doi: 10.1136/adc.40.213.516. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zilva J. F. The origin of the acidosis in hyperlactataemia. Ann Clin Biochem. 1978 Jan;15(1):40–43. doi: 10.1177/000456327801500111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]