Abstract

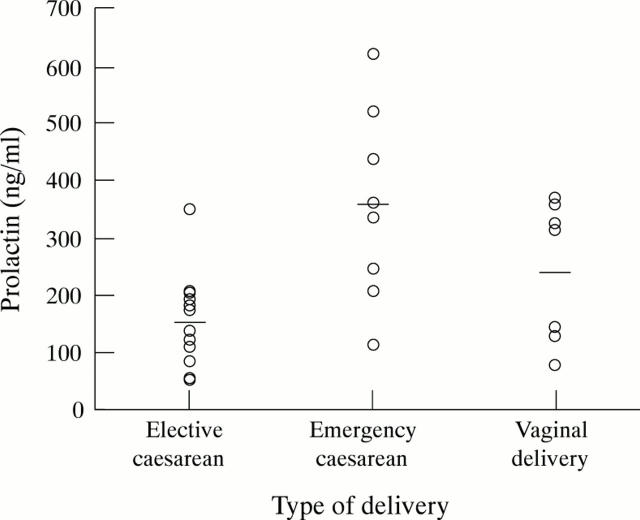

The umbilical venous plasma prolactin concentrations of three groups of term infants were compared immediately after birth. Samples were taken following seven vaginal deliveries, eight emergency caesarean sections performed during labour, and 12 elective caesarean sections before labour. Mean concentrations of prolactin were significantly lower in the elective caesarean section group compared with the labour groups. This result indicates that the fetal hypothalamic-pituitary axis is stimulated during labour which could explain the increase in plasma prolactin concentrations at birth. Keywords: caesarean section; labour; prolactin

Full Text

The Full Text of this article is available as a PDF (61.3 KB).

Figure 1 .

Plasma prolactin concentrations in infants born vaginally or by caesarean section subjected (emergency) or not (elective) to labour. Horizontal lines indicate mean values; each patient is represented by an individual symbol.

Selected References

These references are in PubMed. This may not be the complete list of references from this article.

- Australian collaborative trial of antenatal thyrotropin-releasing hormone (ACTOBAT) for prevention of neonatal respiratory disease. Lancet. 1995 Apr 8;345(8954):877–882. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bird J. A., Spencer J. A., Mould T., Symonds M. E. Endocrine and metabolic adaptation following caesarean section or vaginal delivery. Arch Dis Child Fetal Neonatal Ed. 1996 Mar;74(2):F132–F134. doi: 10.1136/fn.74.2.f132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Christensson K., Siles C., Cabrera T., Belaustequi A., de la Fuente P., Lagercrantz H., Puyol P., Winberg J. Lower body temperatures in infants delivered by caesarean section than in vaginally delivered infants. Acta Paediatr. 1993 Feb;82(2):128–131. doi: 10.1111/j.1651-2227.1993.tb12622.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clarke L., Heasman L., Firth K., Symonds M. E. Influence of route of delivery and ambient temperature on thermoregulation in newborn lambs. Am J Physiol. 1997 Jun;272(6 Pt 2):R1931–R1939. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.1997.272.6.R1931. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dauncey M. J., Gilmour R. S. Regulatory factors in the control of muscle development. Proc Nutr Soc. 1996 Mar;55(1B):543–559. doi: 10.1079/pns19960047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kelly P. A., Djiane J., Postel-Vinay M. C., Edery M. The prolactin/growth hormone receptor family. Endocr Rev. 1991 Aug;12(3):235–251. doi: 10.1210/edrv-12-3-235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liggins G. C. Thyrotrophin-releasing hormone (TRH) and lung maturation. Reprod Fertil Dev. 1995;7(3):443–450. doi: 10.1071/rd9950443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lucas A., Baker B. A., Cole T. J. Plasma prolactin and clinical outcome in preterm infants. Arch Dis Child. 1990 Sep;65(9):977–983. doi: 10.1136/adc.65.9.977. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morrison J. J., Rennie J. M., Milton P. J. Neonatal respiratory morbidity and mode of delivery at term: influence of timing of elective caesarean section. Br J Obstet Gynaecol. 1995 Feb;102(2):101–106. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-0528.1995.tb09060.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Phillips I. D., Anthony R. V., Butler T. G., Ross J. T., McMillen I. C. Hepatic prolactin receptor gene expression increases in the sheep fetus before birth and after cortisol infusion. Endocrinology. 1997 Mar;138(3):1351–1354. doi: 10.1210/endo.138.3.5102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Phillips I. D., Fielke S. L., Young I. R., McMillen I. C. The relative roles of the hypothalamus and cortisol in the control of prolactin gene expression in the anterior pituitary of the sheep fetus. J Neuroendocrinol. 1996 Dec;8(12):929–933. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2826.1996.tb00823.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Royster M., Driscoll P., Kelly P. A., Freemark M. The prolactin receptor in the fetal rat: cellular localization of messenger ribonucleic acid, immunoreactive protein, and ligand-binding activity and induction of expression in late gestation. Endocrinology. 1995 Sep;136(9):3892–3900. doi: 10.1210/endo.136.9.7649097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomas A. L., Jack P. M., Manns J. G., Nathanielsz P. W. Effect of synthetic thyrotrophin releasing hormone on thyrotrophin and prolactin concentractions in the peripheral plasma of the pregnant ewe, lamb fetus and neonatal lamb. Biol Neonate. 1975;26(1-2):109–116. doi: 10.1159/000240722. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Varvarigou A., Vagenakis A. G., Makri M., Beratis N. G. Growth hormone, insulin-like growth factor-I and prolactin in small for gestational age neonates. Biol Neonate. 1994;65(2):94–102. doi: 10.1159/000244034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Varvarigou A., Vagenakis A. G., Makri M., Frimas C., Beratis N. G. Prolactin and growth hormone in perinatal asphyxia. Biol Neonate. 1996;69(2):76–83. doi: 10.1159/000244281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]