Abstract

Background: Previous studies suggest that high risk and low birthweight babies have better outcomes if born in hospitals with level III neonatal intensive care units. Relations between obstetric care, particularly intrapartum interventions and perinatal outcomes, are less well understood, however.

Objective: To investigate effects of obstetric, paediatric, and demographic factors on rates of hospital stillbirths and neonatal mortality.

Methods: Cross sectional data on all 65 maternity units in all Thames Regions, 1994–1996, covering 540 834 live births and stillbirths. Hospital level analyses investigated associations between staffing rates (consultant/junior paediatricians, consultant/junior obstetricians, midwives), facilities (consultant obstetrician/anaesthetist sessions, delivery beds, special care baby unit, neonatal intensive care unit cots, etc), interventions (vaginal births, caesarean sections, forceps, epidurals, inductions, general anaesthetic), parental data (parity, maternal age, social class, deprivation, multiple births), and birthweight standardised stillbirth rates and neonatal mortality.

Results: Unifactorial analyses showed consistent negative associations between measures of obstetric intervention and stillbirth rates. Some measures of staffing, facilities, and parental data also showed significant associations. Scores for interventional, organisational, and parental variables were derived for multifactorial analysis to overcome the statistical problems caused by high intercorrelations between variables. A higher intervention score and higher number of consultant obstetricians per 1000 births were both independently and significantly associated with lower stillbirth rates. Organisational and parental factors were not significant after adjustment. Only Townsend deprivation score was significantly associated with neonatal mortality (positive correlation).

Conclusions: Birthweight adjusted stillbirth rates were significantly lower in units that took a more interventionalist approach and in those with higher levels of consultant obstetric staffing. There were no apparent associations between neonatal death rates and the hospital factors measured here.

Full Text

The Full Text of this article is available as a PDF (232.9 KB).

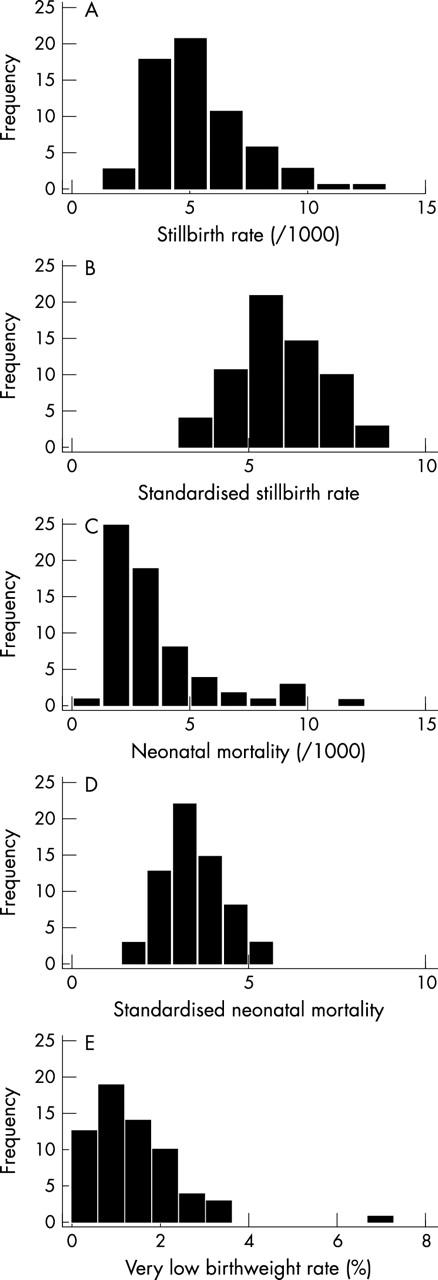

Figure 1 .

Histograms of the crude (A) and standardised (B) stillbirth rates and crude (C) and standardised (D) neonatal mortality and the very low birthweight (< 1500 g) rates (E), Thames hospitals, 1994–1996 (n = 64).

Selected References

These references are in PubMed. This may not be the complete list of references from this article.

- Bakketeig L. S., Hoffman H. J., Sternthal P. M. Obstetric service and perinatal mortality in Norway. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand Suppl. 1978;77:3–19. doi: 10.3109/00016347809157954. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chamberlain G. Background to perinatal health. Lancet. 1979 Nov 17;2(8151):1061–1063. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(79)92454-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cole S. K., Macfarlane A. Safety and place of birth in Scotland. J Public Health Med. 1995 Mar;17(1):17–24. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Field D., Draper E. S. Survival and place of delivery following preterm birth: 1994-96. Arch Dis Child Fetal Neonatal Ed. 1999 Mar;80(2):F111–F114. doi: 10.1136/fn.80.2.f111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Finnström O., Olausson P. O., Sedin G., Serenius F., Svenningsen N., Thiringer K., Tunell R., Wennergren M., Wesström G. The Swedish national prospective study on extremely low birthweight (ELBW) infants. Incidence, mortality, morbidity and survival in relation to level of care. Acta Paediatr. 1997 May;86(5):503–511. doi: 10.1111/j.1651-2227.1997.tb08921.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Florey C. D., Taylor D. J. The relation between antenatal care and birth weight. Rev Epidemiol Sante Publique. 1994;42(3):191–197. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fresson J., Guillemin F., André M., Abdouch A., Fontaine B., Vert P. Influence du mode de transfert sur le devenir à court terme des enfants à haut risque périnatal. Arch Pediatr. 1997 Mar;4(3):219–226. doi: 10.1016/s0929-693x(97)87234-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hellier J. L., Goldstein H. The use of birthweight and gestation to assess perinatal mortality risk. J Epidemiol Community Health. 1979 Sep;33(3):183–185. doi: 10.1136/jech.33.3.183. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horbar J. D., Badger G. J., Lewit E. M., Rogowski J., Shiono P. H. Hospital and patient characteristics associated with variation in 28-day mortality rates for very low birth weight infants. Vermont Oxford Network. Pediatrics. 1997 Feb;99(2):149–156. doi: 10.1542/peds.99.2.149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joffe M., Chapple J., Paterson C., Beard R. W. What is the optimal caesarean section rate? An outcome based study of existing variation. J Epidemiol Community Health. 1994 Aug;48(4):406–411. doi: 10.1136/jech.48.4.406. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Powell S. L., Holt V. L., Hickok D. E., Easterling T., Connell F. A. Recent changes in delivery site of low-birth-weight infants in Washington: impact on birth weight-specific mortality. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1995 Nov;173(5):1585–1592. doi: 10.1016/0002-9378(95)90653-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richardson D. K., Gray J. E., Gortmaker S. L., Goldmann D. A., Pursley D. M., McCormick M. C. Declining severity adjusted mortality: evidence of improving neonatal intensive care. Pediatrics. 1998 Oct;102(4 Pt 1):893–899. doi: 10.1542/peds.102.4.893. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shearer E. L. Cesarean section: medical benefits and costs. Soc Sci Med. 1993 Nov;37(10):1223–1231. doi: 10.1016/0277-9536(93)90334-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stilwell J., Szczepura A., Mugford M. Factors affecting the outcome of maternity care. 1. Relationship between staffing and perinatal deaths at the hospital of birth. J Epidemiol Community Health. 1988 Jun;42(2):157–169. doi: 10.1136/jech.42.2.157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strobino D. M., Ensminger M. E., Kim Y. J., Nanda J. Mechanisms for maternal age differences in birth weight. Am J Epidemiol. 1995 Sep 1;142(5):504–514. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a117668. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tucker Janet, UK Neonatal Staffing Study Group Patient volume, staffing, and workload in relation to risk-adjusted outcomes in a random stratified sample of UK neonatal intensive care units: a prospective evaluation. Lancet. 2002 Jan 12;359(9301):99–107. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(02)07366-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilkinson C., McIlwaine G., Boulton-Jones C., Cole S. Is a rising caesarean section rate inevitable? Br J Obstet Gynaecol. 1998 Jan;105(1):45–52. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-0528.1998.tb09349.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yeast J. D., Poskin M., Stockbauer J. W., Shaffer S. Changing patterns in regionalization of perinatal care and the impact on neonatal mortality. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1998 Jan;178(1 Pt 1):131–135. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9378(98)70639-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]