Abstract

Background: Maternal subclinical hypothyroidism is a cause of poor neurodevelopment outcome in the offspring. Although iodine deficiency is the most common cause of hypothyroidism world wide, there are no screening programmes for it in the United Kingdom where the population is assumed to be iodine replete.

Objective: To determine the prevalence of reduced iodine intake by measuring urinary iodide concentrations in pregnant and non-pregnant women from the north east of England.

Methods: Urinary iodide excretion (UIE) rate was estimated using inductively coupled mass spectrometry in 227 women at 15 weeks gestation and in 227 non-pregnant age matched controls. A reduced intake of iodine is indicated by a concentration in urine of less than 50 µg/l or less than 0.05 µg iodine/mmol creatinine.

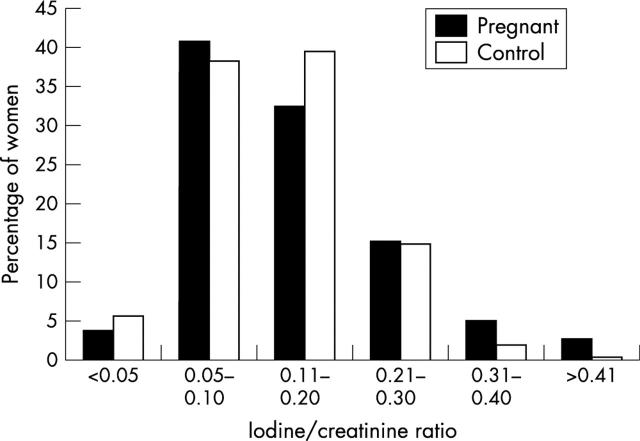

Results: Eight (3.5%) pregnant women and 13 (5.7%) controls had a reduced iodine/creatinine ratio. These values were higher when UIE was expressed as iodine concentration: 16 (7%) and 20 (8.8%) respectively. Ninety (40%) of the pregnant women had a UIE of 0.05–0.10, which is consistent with borderline deficiency.

Conclusion: In this study, 3.5% of pregnant women had evidence of iodine deficiency, and 40% may be borderline deficient. Larger scale studies are required to estimate the true prevalence of iodine deficiency in the United Kingdom.

Full Text

The Full Text of this article is available as a PDF (90.8 KB).

Figure 1.

Distribution of iodine/creatinine ratio. A ratio of 0.05 shows iodine deficiency, and 0.05–0.10 is borderline.

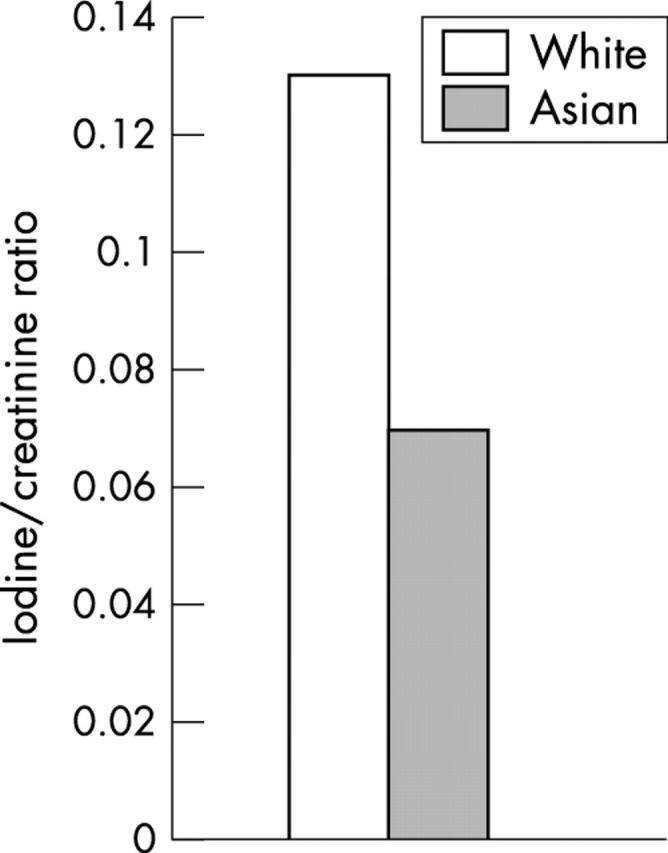

Figure 2.

Iodine/creatinine ratio for Asian and white women.

Figure 3.

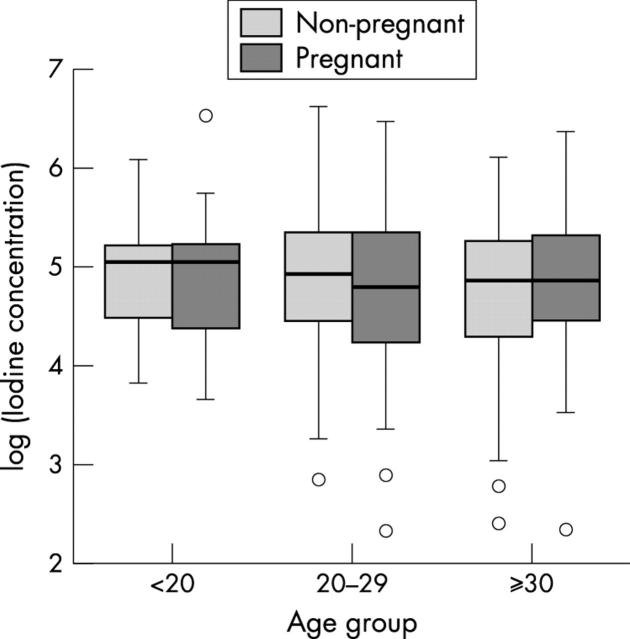

Box plots of log (urinary iodine concentration).

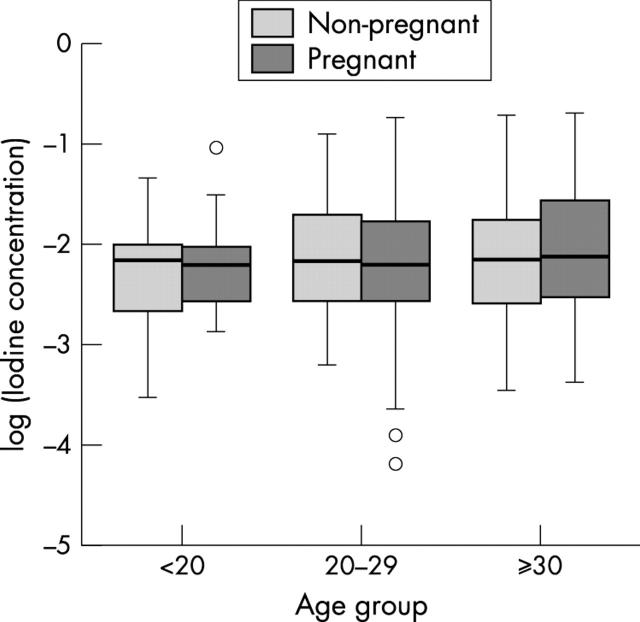

Figure 4.

Box plots of log (urinary iodine/creatinine ratio).

Selected References

These references are in PubMed. This may not be the complete list of references from this article.

- Andersen S., Pedersen K. M., Pedersen I. B., Laurberg P. Variations in urinary iodine excretion and thyroid function. A 1-year study in healthy men. Eur J Endocrinol. 2001 May;144(5):461–465. doi: 10.1530/eje.0.1440461. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bongers-Schokking J. J., Koot H. M., Wiersma D., Verkerk P. H., de Muinck Keizer-Schrama S. M. Influence of timing and dose of thyroid hormone replacement on development in infants with congenital hypothyroidism. J Pediatr. 2000 Mar;136(3):292–297. doi: 10.1067/mpd.2000.103351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brent G. A. Maternal thyroid function: interpretation of thyroid function tests in pregnancy. Clin Obstet Gynecol. 1997 Mar;40(1):3–15. doi: 10.1097/00003081-199703000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Delange F., Wolff P., Gnat D., Dramaix M., Pilchen M., Vertongen F. Iodine deficiency during infancy and early childhood in Belgium: does it pose a risk to brain development? Eur J Pediatr. 2001 Apr;160(4):251–254. doi: 10.1007/s004310000707. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dunn J. T. Endemic goiter and cretinism: an update on iodine status. J Pediatr Endocrinol Metab. 2001;14 (Suppl 6):1469–1473. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giannessi D., Andreassi M. G., Del Ry S., Clerico A., Colombo M. G., Dini N. Possibility of age regulation of the natriuretic peptide C-receptor in human platelets. J Endocrinol Invest. 2001 Jan;24(1):8–16. doi: 10.1007/BF03343802. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glinoer D., De Nayer P., Delange F., Lemone M., Toppet V., Spehl M., Grün J. P., Kinthaert J., Lejeune B. A randomized trial for the treatment of mild iodine deficiency during pregnancy: maternal and neonatal effects. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1995 Jan;80(1):258–269. doi: 10.1210/jcem.80.1.7829623. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haddow J. E., Palomaki G. E., Allan W. C., Williams J. R., Knight G. J., Gagnon J., O'Heir C. E., Mitchell M. L., Hermos R. J., Waisbren S. E. Maternal thyroid deficiency during pregnancy and subsequent neuropsychological development of the child. N Engl J Med. 1999 Aug 19;341(8):549–555. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199908193410801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hollowell J. G., Staehling N. W., Hannon W. H., Flanders D. W., Gunter E. W., Maberly G. F., Braverman L. E., Pino S., Miller D. T., Garbe P. L. Iodine nutrition in the United States. Trends and public health implications: iodine excretion data from National Health and Nutrition Examination Surveys I and III (1971-1974 and 1988-1994) J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1998 Oct;83(10):3401–3408. doi: 10.1210/jcem.83.10.5168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morreale de Escobar G., Obregón M. J., Escobar del Rey F. Is neuropsychological development related to maternal hypothyroidism or to maternal hypothyroxinemia? J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2000 Nov;85(11):3975–3987. doi: 10.1210/jcem.85.11.6961. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pardede L. V., Hardjowasito W., Gross R., Dillon D. H., Totoprajogo O. S., Yosoprawoto M., Waskito L., Untoro J. Urinary iodine excretion is the most appropriate outcome indicator for iodine deficiency at field conditions at district level. J Nutr. 1998 Jul;128(7):1122–1126. doi: 10.1093/jn/128.7.1122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pedersen K. M., Laurberg P., Iversen E., Knudsen P. R., Gregersen H. E., Rasmussen O. S., Larsen K. R., Eriksen G. M., Johannesen P. L. Amelioration of some pregnancy-associated variations in thyroid function by iodine supplementation. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1993 Oct;77(4):1078–1083. doi: 10.1210/jcem.77.4.8408456. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pop V. J., van Baar A. L., Vulsma T. Should all pregnant women be screened for hypothyroidism? Lancet. 1999 Oct 9;354(9186):1224–1225. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(99)00331-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Porterfield S. P., Hendrich C. E. The role of thyroid hormones in prenatal and neonatal neurological development--current perspectives. Endocr Rev. 1993 Feb;14(1):94–106. doi: 10.1210/edrv-14-1-94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rasmussen L. B., Ovesen L., Christiansen E. Day-to-day and within-day variation in urinary iodine excretion. Eur J Clin Nutr. 1999 May;53(5):401–407. doi: 10.1038/sj.ejcn.1600762. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomson C. D., Woodruffe S., Colls A. J., Joseph J., Doyle T. C. Urinary iodine and thyroid status of New Zealand residents. Eur J Clin Nutr. 2001 May;55(5):387–392. doi: 10.1038/sj.ejcn.1601170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tillotson S. L., Fuggle P. W., Smith I., Ades A. E., Grant D. B. Relation between biochemical severity and intelligence in early treated congenital hypothyroidism: a threshold effect. BMJ. 1994 Aug 13;309(6952):440–445. doi: 10.1136/bmj.309.6952.440. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]