Abstract

AIMS/BACKGROUND—This investigation determined eye care utilisation patterns in a rural county in Ireland. Population based estimates of visual impairment and glaucoma were available, so the two studies will optimise planning for eye care services for the county. METHODS—Roscommon has a population of 55 000 served by one ophthalmologist and two optometrists. Data were collected on all outpatient visits for all providers for a 3 month period. Information was abstracted on demographics, presenting and final diagnoses. Expected number of visits for glaucoma were calculated using the population structure and rates of glaucoma, and assuming one visit per year per glaucoma patient. RESULTS—1398 patients had a total of 1442 visits in 3 months. A third of the visits were to optometrists, and all but 21 visits were for normal eye examinations or glasses. The majority of children aged less than 16 years, and people older than 60 years were seen by the ophthalmologist. Among children, 81% of all visits were to the ophthalmologist and 92% were classified as a normal examination. Only an estimated 188 visits per year for glaucoma were observed, compared with 1100 expected. CONCLUSION—In this rural county, many of the visits to the ophthalmologist were for normal eye examination, particularly among children. Screening algorithms which would free the ophthalmologist to see more complicated problems could be considered. There is an underutilisation of services by glaucoma patients. Reasons for this are described.

Full Text

The Full Text of this article is available as a PDF (116.5 KB).

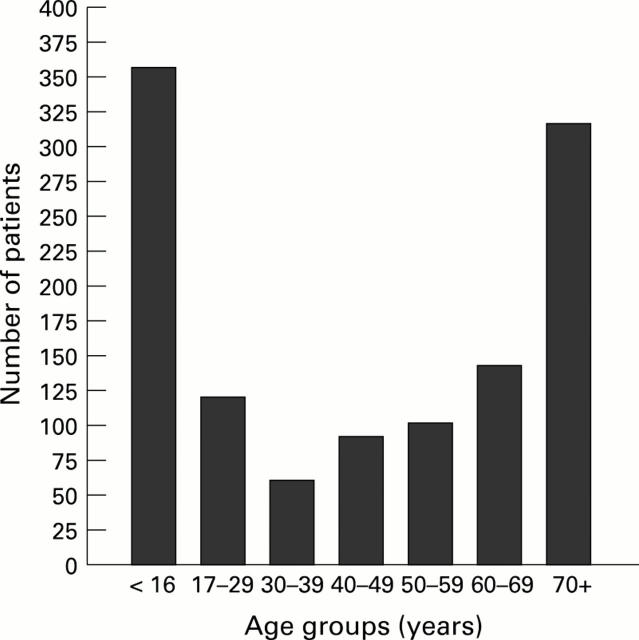

Figure 1 .

Age distribution of 1398 patients seeking eye care in Roscommon County.

Selected References

These references are in PubMed. This may not be the complete list of references from this article.

- Brilliant G. E., Brilliant L. B. Using social epidemiology to understand who stays blind and who gets operated for cataract in a rural setting. Soc Sci Med. 1985;21(5):553–558. doi: 10.1016/0277-9536(85)90040-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coffey M., Reidy A., Wormald R., Xian W. X., Wright L., Courtney P. Prevalence of glaucoma in the west of Ireland. Br J Ophthalmol. 1993 Jan;77(1):17–21. doi: 10.1136/bjo.77.1.17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dielemans I., Vingerling J. R., Wolfs R. C., Hofman A., Grobbee D. E., de Jong P. T. The prevalence of primary open-angle glaucoma in a population-based study in The Netherlands. The Rotterdam Study. Ophthalmology. 1994 Nov;101(11):1851–1855. doi: 10.1016/s0161-6420(94)31090-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gupta S. K., Murthy G. V. Where do persons with blindness caused by cataracts in rural areas of India seek treatment and why? Arch Ophthalmol. 1995 Oct;113(10):1337–1340. doi: 10.1001/archopht.1995.01100100125046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Javitt J. C., Chiang Y. P. Preparing for managed competition. Utilization of ambulatory eye care visits to ophthalmologists. Arch Ophthalmol. 1993 Aug;111(8):1034–1035. doi: 10.1001/archopht.1993.01090080030012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Javitt J. C. Preventing blindness in Americans: the need for eye health education. Surv Ophthalmol. 1995 Jul-Aug;40(1):41–44. doi: 10.1016/s0039-6257(95)80045-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klein B. E., Klein R., Sponsel W. E., Franke T., Cantor L. B., Martone J., Menage M. J. Prevalence of glaucoma. The Beaver Dam Eye Study. Ophthalmology. 1992 Oct;99(10):1499–1504. doi: 10.1016/s0161-6420(92)31774-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leibowitz H. M., Krueger D. E., Maunder L. R., Milton R. C., Kini M. M., Kahn H. A., Nickerson R. J., Pool J., Colton T. L., Ganley J. P. The Framingham Eye Study monograph: An ophthalmological and epidemiological study of cataract, glaucoma, diabetic retinopathy, macular degeneration, and visual acuity in a general population of 2631 adults, 1973-1975. Surv Ophthalmol. 1980 May-Jun;24(Suppl):335–610. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lindblom B., Thorburn W. Prevalence of visual field defects due to capsular and simple glaucoma in Hälsingland, Sweden. Acta Ophthalmol (Copenh) 1982 Jun;60(3):353–361. doi: 10.1111/j.1755-3768.1982.tb03025.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tielsch J. M., Sommer A., Katz J., Royall R. M., Quigley H. A., Javitt J. Racial variations in the prevalence of primary open-angle glaucoma. The Baltimore Eye Survey. JAMA. 1991 Jul 17;266(3):369–374. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tielsch J. M. The epidemiology and control of open angle glaucoma: a population-based perspective. Annu Rev Public Health. 1996;17:121–136. doi: 10.1146/annurev.pu.17.050196.001005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vernon S. A., Henry D. J., Cater L., Jones S. J. Screening for glaucoma in the community by non-ophthalmologically trained staff using semi automated equipment. Eye (Lond) 1990;4(Pt 1):89–97. doi: 10.1038/eye.1990.10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]