Abstract

AIM—To investigate full field monocular optokinetic nystagmus (OKN) in patients with age-related maculopathy (ARM) and relative central scotoma. METHODS—Six patients aged 59-88 years with bilateral ARM and an aged-matched control group of six patients aged 54-83 years were examined. Visual fields were assessed with a Humphrey field analyser using the threshold 30-1 routine. Monocular full field horizontal optokinetic stimuli were presented on a hemicylindrical screen subtending 172° horizontally and 50° vertically. The stimulus was a projected random dot pattern and three stimulus velocities were used, 30, 50, and 70°/s in both nasalward and temporalward directions. Each trial lasted between 30 and 40 seconds and eye movements were monitored using infrared oculography. RESULTS—The ARM patients had relative central scotomas with an average depth of 10 dB. Neither the ARM nor the age-matched groups displayed any directional preponderance or a buildup of the slow phase eye velocity with time. No statistically significant difference in the gain was found between the two groups (p>0.05). CONCLUSIONS—Marked central field loss in ARM does not significantly impair OKN gain. This supports the view that complete central retinal integrity is by no means essential and that the peripheral retina provides an important input to the generation of OKN.

Full Text

The Full Text of this article is available as a PDF (116.6 KB).

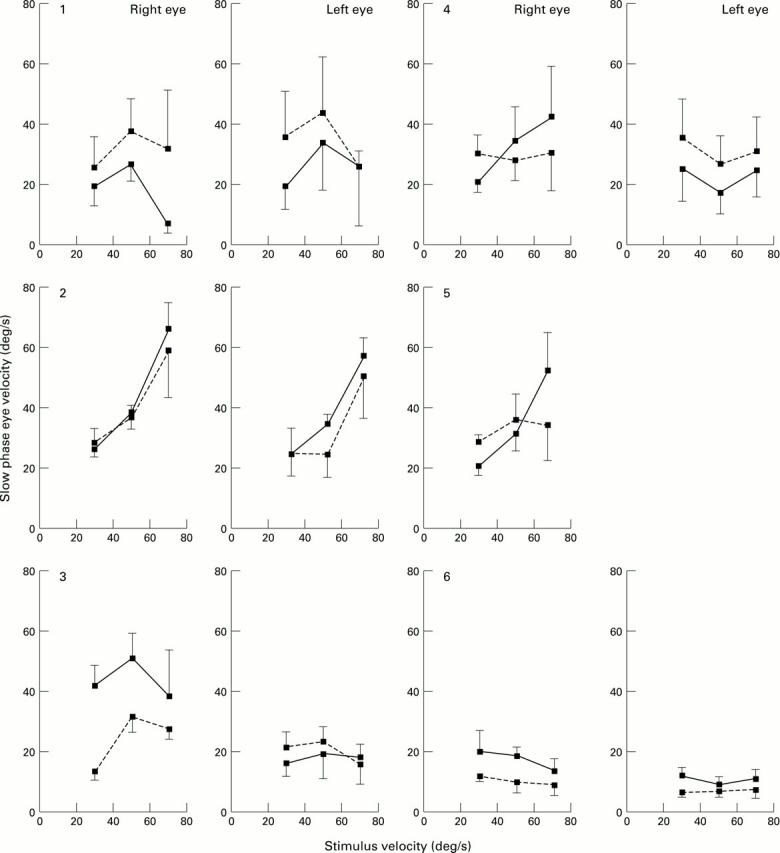

Figure 1 .

The relation between slow phase velocity and stimulus velocity for the right and left eye of each of six age-matched control patients for unidirectional optokinetic stimulation. Three stimulus velocities are illustrated: 30, 50, and 70°/s. The direction of the stimulus was either nasal-temporal (solid line) or temporal-nasal (broken line). The vertical bars indicate the standard deviation of the mean of 10 slow phases.

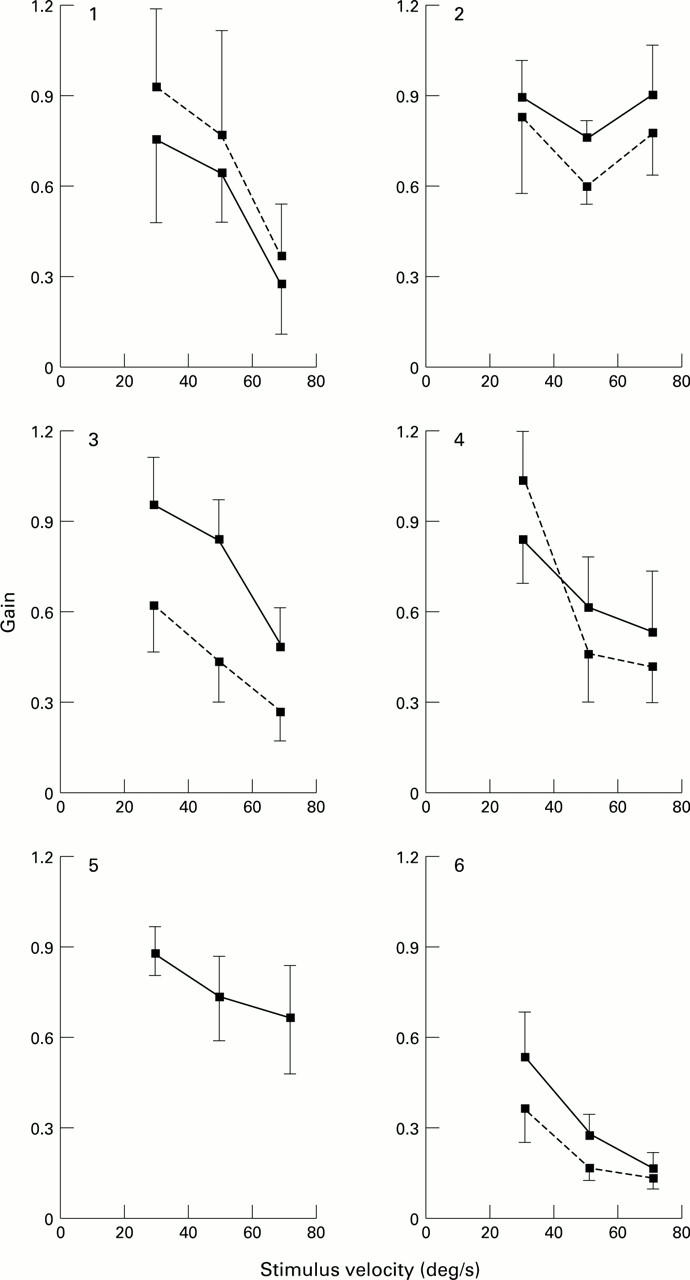

Figure 2 .

The relation between optokinetic gain and stimulus velocity for each of the six age-matched control patients. The direction of the stimulus was either nasal-temporal or temporal-nasal and the data of the optokinetic responses, elicited under both conditions, have been averaged for each patient's right (solid line) and left eye (broken line). Vertical bars represent the standard deviation of the mean of 20 slow phases (10 measurements for each of the two directions).

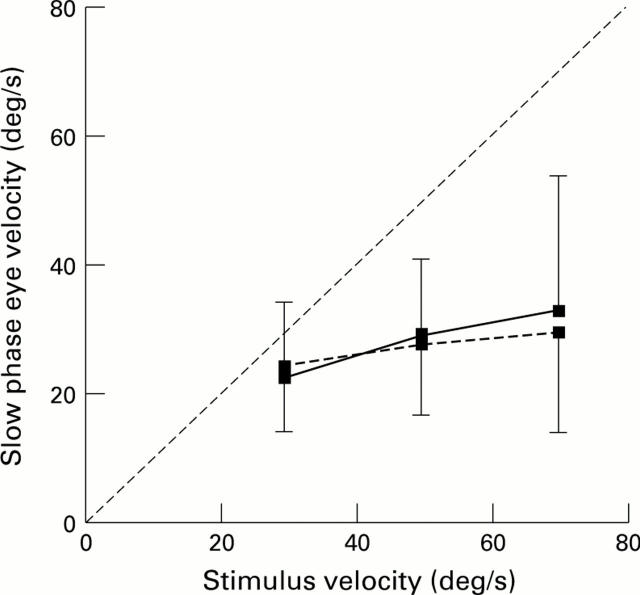

Figure 3 .

The relation between slow phase velocity and stimulus velocity for the right and left eye of each patient with ARM under unidirectional optokinetic stimulation. Three stimulus velocities are illustrated: 30, 50, and 70°/s. The direction of the stimulus was either nasal-temporal (solid line) or temporal-nasal (broken line). The vertical bars indicate the standard deviation of the mean of 10 slow phases. The left eye of patient No 5 was not examined.

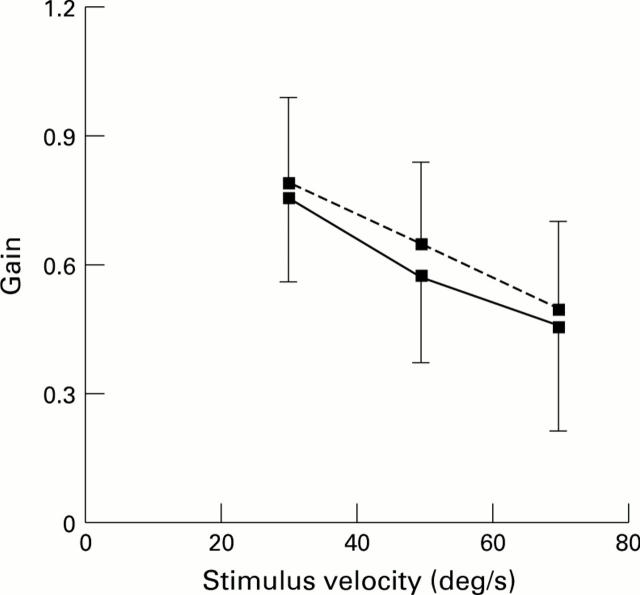

Figure 4 .

The relation between optokinetic gain and stimulus velocity for each of the six patients with ARM. The direction of the stimulus was either nasal-temporal or temporal-nasal and the data of the optokinetic responses, elicited under both conditions, have been averaged for each patient's right (solid line) and left eye (broken line). Vertical bars represent the standard deviation of the mean of 20 slow phases (10 measurements for each of the two directions) The left eye of patient No 5 was not examined.

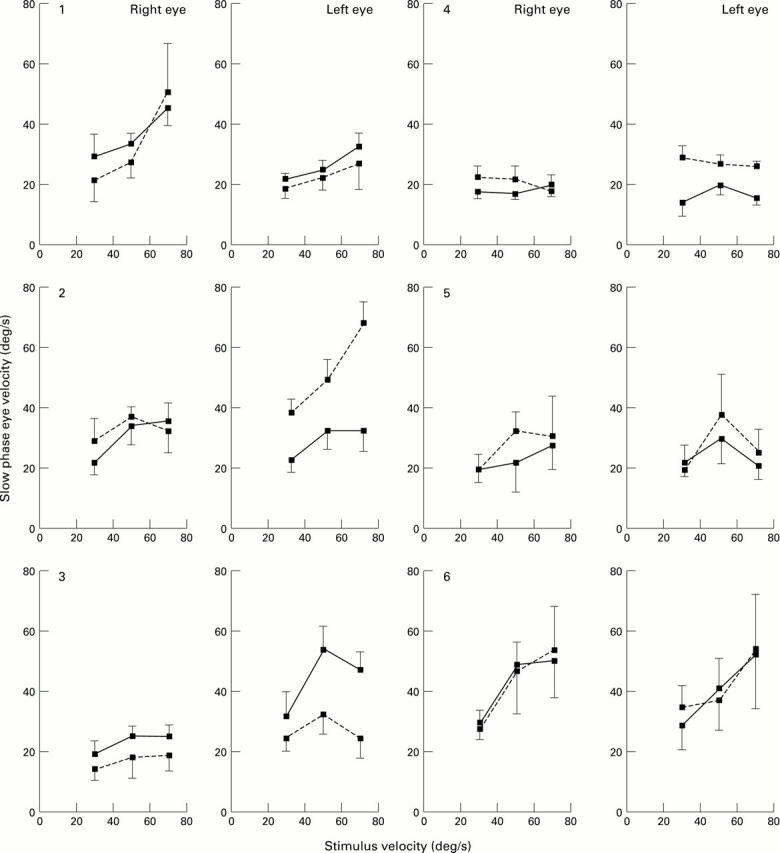

Figure 5 .

The relation between the mean slow phase eye velocity and stimulus velocity of the six patients with ARM, for nasal-temporal (solid line) and temporal-nasal (broken line) directions. Vertical bars indicate the standard deviation of the mean which is made up of the 11 ARM eyes tested. The line at 45° to the two coordinates represents a gain of unity.

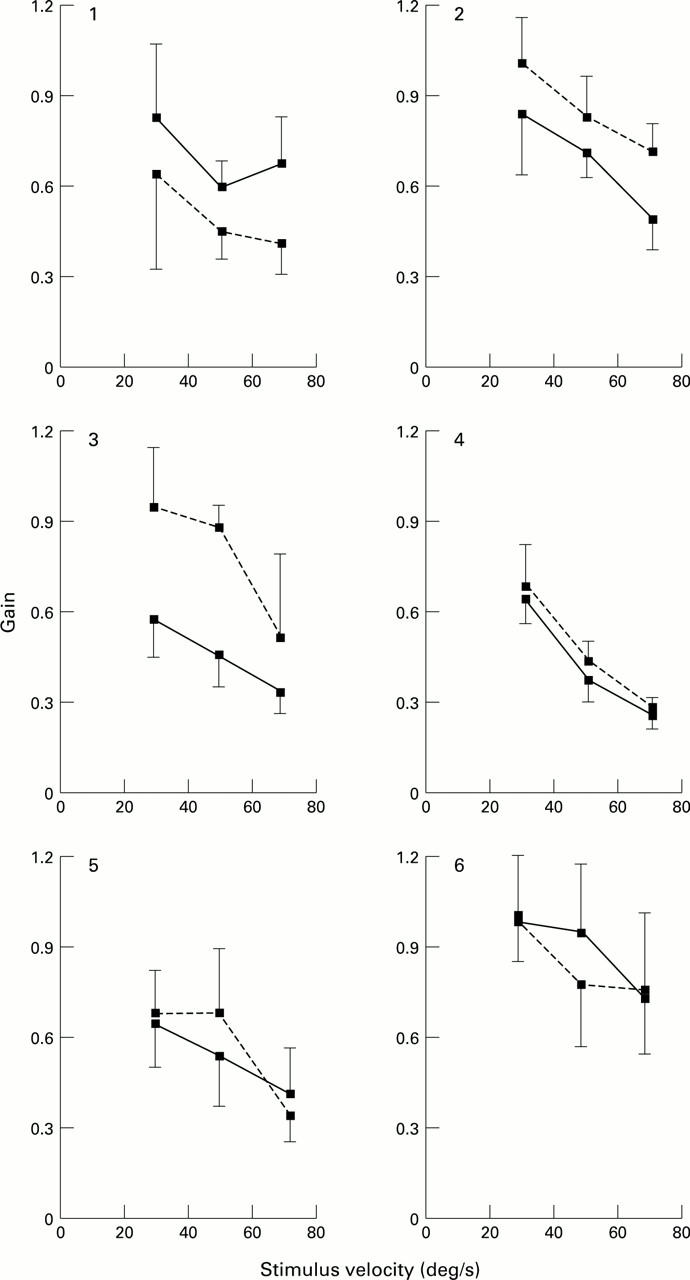

Figure 6 .

The effect of full field unidirectional stimulus motion on the averaged gain for the age-matched control (broken line) and age-related maculopathy (ARM) (solid line) patient groups. Vertical bars indicate the standard deviation of the mean for the control and ARM groups.

Selected References

These references are in PubMed. This may not be the complete list of references from this article.

- Abadi R. V., Dickinson C. M. The influence of preexisting oscillations on the binocular optokinetic response. Ann Neurol. 1985 Jun;17(6):578–586. doi: 10.1002/ana.410170609. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Abadi R. V., Pascal E. The effects of simultaneous central and peripheral field motion on the optokinetic response. Vision Res. 1991;31(12):2219–2225. doi: 10.1016/0042-6989(91)90174-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baloh R. W., Jacobson K. M., Socotch T. M. The effect of aging on visual-vestibuloocular responses. Exp Brain Res. 1993;95(3):509–516. doi: 10.1007/BF00227144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baloh R. W., Yee R. D., Honrubia V. Optokinetic asymmetry in patients with maldeveloped foveas. Brain Res. 1980 Mar 17;186(1):211–216. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(80)90268-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bressler N. M., Bressler S. B., Fine S. L. Age-related macular degeneration. Surv Ophthalmol. 1988 May-Jun;32(6):375–413. doi: 10.1016/0039-6257(88)90052-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheng M., Outerbridge J. S. Optokinetic nystagmus during selective retinal stimulation. Exp Brain Res. 1975 Aug 14;23(2):129–139. doi: 10.1007/BF00235455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chiba Y., Furuya N. [Aging and reference values of the parameters in optokinetic nystagmus]. Nihon Jibiinkoka Gakkai Kaiho. 1989 Sep;92(9):1416–1423. doi: 10.3950/jibiinkoka.92.1416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dickinson C. M., Abadi R. V. Pursuit and optokinetic responses in latent/manifest latent nystagmus. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 1990 Aug;31(8):1599–1614. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dubois M. F., Collewijn H. Optokinetic reactions in man elicited by localized retinal motion stimuli. Vision Res. 1979;19(10):1105–1115. doi: 10.1016/0042-6989(79)90005-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dubois M. F., Collewijn H. Optokinetic reactions in man elicited by localized retinal motion stimuli. Vision Res. 1979;19(10):1105–1115. doi: 10.1016/0042-6989(79)90005-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gresty M., Halmagyi M. Following eye movements on the absence of central vision. Acta Otolaryngol. 1979 May-Jun;87(5-6):477–483. doi: 10.3109/00016487909126455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Halmagyi G. M., Gresty M. A., Leech J. Reversed optokinetic nystagmus (OKN): mechanism and clinical significance. Ann Neurol. 1980 May;7(5):429–435. doi: 10.1002/ana.410070507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harris L. R., Lewis T. L., Maurer D. Brain stem and cortical contributions to the generation of horizontal optokinetic eye movements in humans. Vis Neurosci. 1993 Mar-Apr;10(2):247–259. doi: 10.1017/s0952523800003655. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Howard I. P., Ohmi M. The efficiency of the central and peripheral retina in driving human optokinetic nystagmus. Vision Res. 1984;24(9):969–976. doi: 10.1016/0042-6989(84)90072-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Magnusson M., Pyykkö I., Jäntti V. Effect of alertness and visual attention on optokinetic nystagmus in humans. Am J Otolaryngol. 1985 Nov-Dec;6(6):419–425. doi: 10.1016/s0196-0709(85)80020-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Naegele J. R., Held R. The postnatal development of monocular optokinetic nystagmus in infants. Vision Res. 1982;22(3):341–346. doi: 10.1016/0042-6989(82)90149-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Norcia A. M., Garcia H., Humphry R., Holmes A., Hamer R. D., Orel-Bixler D. Anomalous motion VEPs in infants and in infantile esotropia. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 1991 Feb;32(2):436–439. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pola J., Wyatt H. J. The role of attention and cognitive processes. Rev Oculomot Res. 1993;5:371–392. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramachandran V. S., Gregory R. L. Perceptual filling in of artificially induced scotomas in human vision. Nature. 1991 Apr 25;350(6320):699–702. doi: 10.1038/350699a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sarks S. H. Ageing and degeneration in the macular region: a clinico-pathological study. Br J Ophthalmol. 1976 May;60(5):324–341. doi: 10.1136/bjo.60.5.324. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schor C. M., Levi D. M. Disturbances of small-field horizontal and vertical optokinetic nystagmus in amblyopia. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 1980 Jun;19(6):668–683. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schor C. M., Narayan V., Westall C. Postnatal development of optokinetic after nystagmus in human infants. Vision Res. 1983;23(12):1643–1647. doi: 10.1016/0042-6989(83)90178-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sergent J. An investigation into perceptual completion in blind areas of the visual field. Brain. 1988 Apr;111(Pt 2):347–373. doi: 10.1093/brain/111.2.347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simons B., Büttner U. The influence of age on optokinetic nystagmus. Eur Arch Psychiatry Neurol Sci. 1985;234(6):369–373. doi: 10.1007/BF00386053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swann P. G., Lovie-Kitchin J. E. Age-related maculopathy. I: A review of its morphology and effects on visual function. Ophthalmic Physiol Opt. 1990 Apr;10(2):149–158. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-1313.1990.tb00969.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ura M., Pfaltz C. R., Allum J. H. The effect of age on the visuo- and vestibulo-ocular reflexes of elderly patients with vertigo. Acta Otolaryngol Suppl. 1991;481:399–402. doi: 10.3109/00016489109131431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Die G. C., Collewijn H. Control of human optokinetic nystagmus by the central and peripheral retina: effects of partial visual field masking, scotopic vision and central retinal scotomata. Brain Res. 1986 Sep 24;383(1-2):185–194. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(86)90019-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wattam-Bell J. The development of maximum displacement limits for discrimination of motion direction in infancy. Vision Res. 1992 Apr;32(4):621–630. doi: 10.1016/0042-6989(92)90178-l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Westall C. A., Schor C. M. Asymmetries of optokinetic nystagmus in amblyopia: the effect of selected retinal stimulation. Vision Res. 1985;25(10):1431–1438. doi: 10.1016/0042-6989(85)90221-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yee R. D., Baloh R. W., Honrubia V. Eye movement abnormalities in rod monochromacy. Ophthalmology. 1981 Oct;88(10):1010–1018. doi: 10.1016/s0161-6420(81)80029-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Young R. W. Pathophysiology of age-related macular degeneration. Surv Ophthalmol. 1987 Mar-Apr;31(5):291–306. doi: 10.1016/0039-6257(87)90115-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zackon D. H., Sharpe J. A. Smooth pursuit in senescence. Effects of target acceleration and velocity. Acta Otolaryngol. 1987 Sep-Oct;104(3-4):290–297. doi: 10.3109/00016488709107331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Die G., Collewijn H. Optokinetic nystagmus in man. Role of central and peripheral retina and occurrence of asymmetries. Hum Neurobiol. 1982;1(2):111–119. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Hof-van Duin J., Mohn G. Monocular and binocular optokinetic nystagmus in humans with defective stereopsis. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 1986 Apr;27(4):574–583. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]