Abstract

AIMS—To identify variations in posterior vitreous detachment (PVD) and establish a clinical classification system for PVD. METHODS—400 consecutive eyes were examined using biomicroscopy and vitreous photography and classified the PVD variations—complete PVD with collapse, complete PVD without collapse, partial PVD with thickened posterior vitreous cortex (TPVC), or partial PVD without TPVC. RESULTS—In each PVD type, the most frequently seen ocular pathologies were as follows: in complete PVD with collapse (186 eyes), age related changes without vitreoretinal diseases (77 eyes, 41.4%) and high myopia (55 eyes, 29.6%); in complete PVD without collapse (39 eyes), uveitis (23 eyes, 59.0%) and central retinal vein occlusion (8 eyes, 20.5%); in partial PVD with TPVC (64 eyes), proliferative diabetic retinopathy (30 eyes, 46.9%); and in partial PVD without TPVC (111 eyes), age related changes without vitreoretinal diseases (62 eyes, 55.9%). This PVD categorisation was significantly associated with the prevalence of each vitreoretinal disease (p<0.0001, χ2 test on contingency table). CONCLUSIONS—PVD variations can be classified into four types, which is clinically useful because each type corresponds well to specific vitreoretinal changes.

Full Text

The Full Text of this article is available as a PDF (176.4 KB).

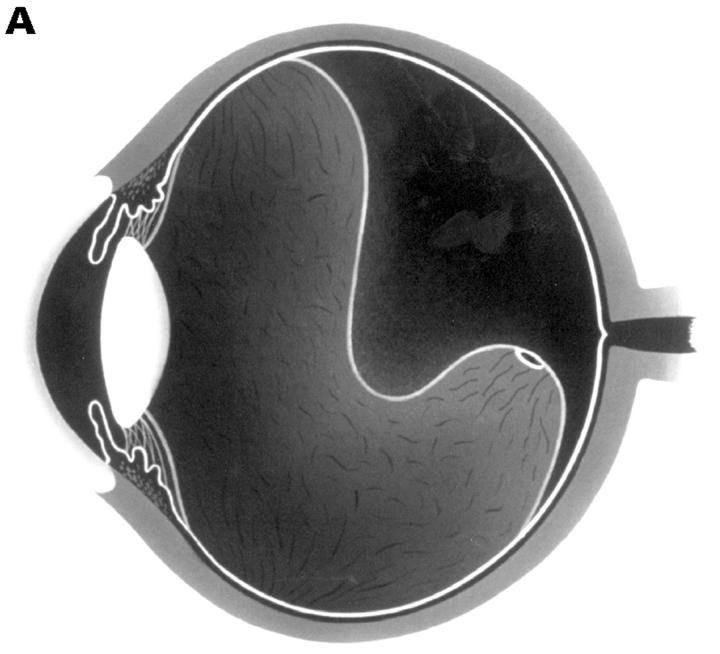

Figure 1 .

(A) Schematic sketch of complete posterior vitreous detachment (PVD) with collapse. The posterior vitreous cortex has a characteristically sigmoidal shape. (B) In a patient who complained of floaters in his visual field, the biomicroscopic vitreous examination revealed complete PVD. The vitreous gel was mildly condensed and, with ocular movement, the posterior vitreous cortex (arrows) oscillated in a smooth, wavy motion. This case was classified as complete PVD with collapse.

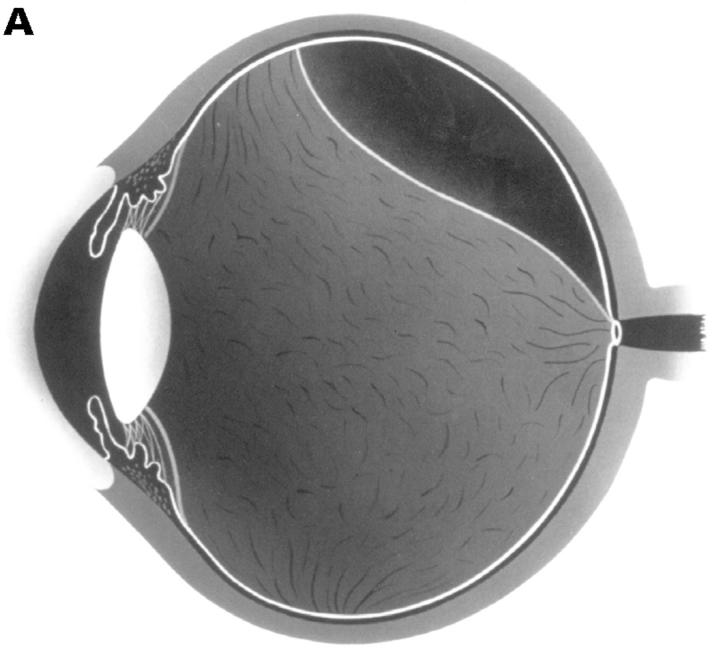

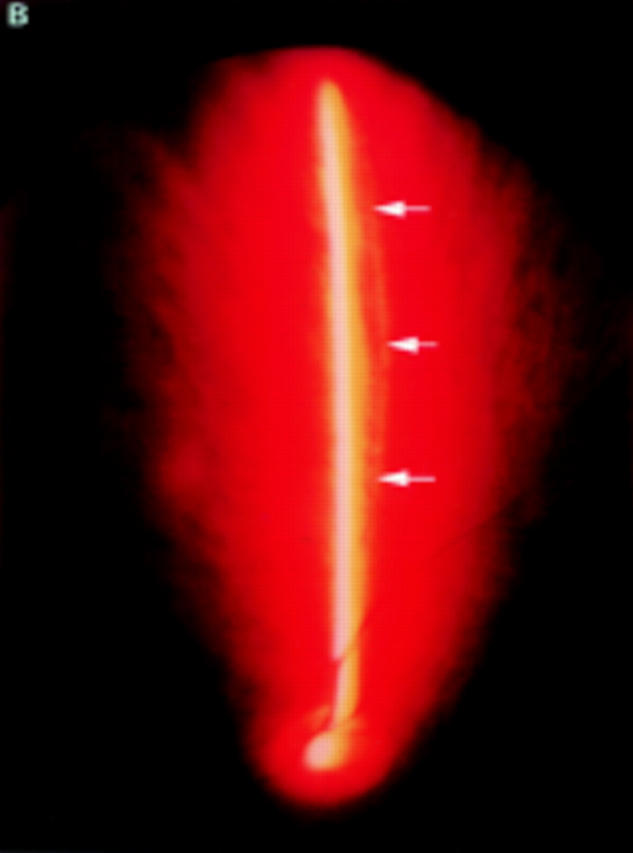

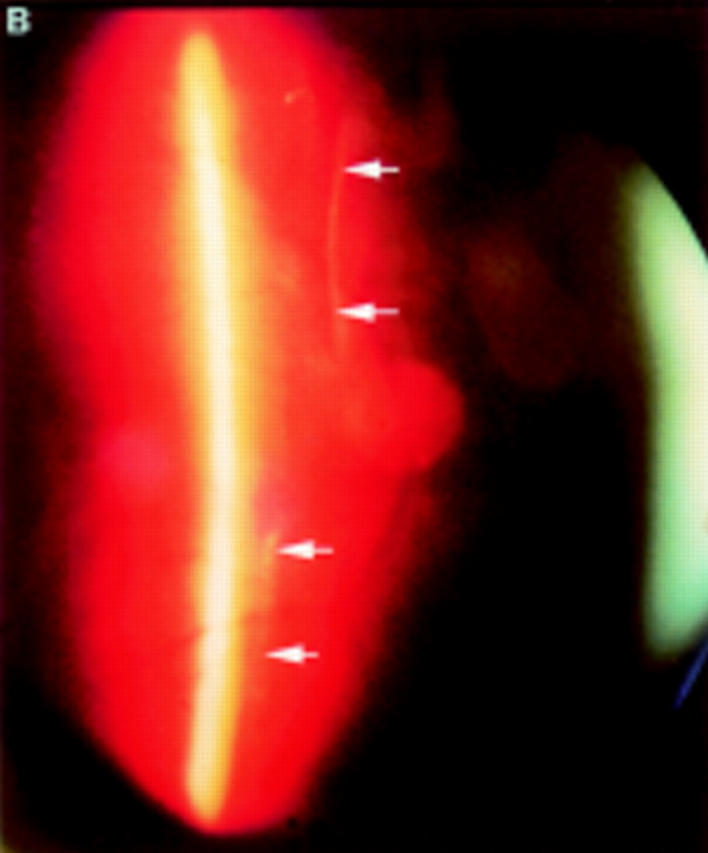

Figure 2 .

(A) Schematic sketch of complete posterior vitreous detachment (PVD) without collapse. The posterior vitreous cortex is convex and shallowly detached. (B) In a patient with uveitis, the posterior vitreous cortex (arrows) is shallowly detached from the retina; vitreous opacities are observed in the vitreous gel and the posterior vitreous cortex is convex. The vitreous gel is condensed and has minimal mobility even with rapid ocular movement. This case was classified as complete PVD without collapse.

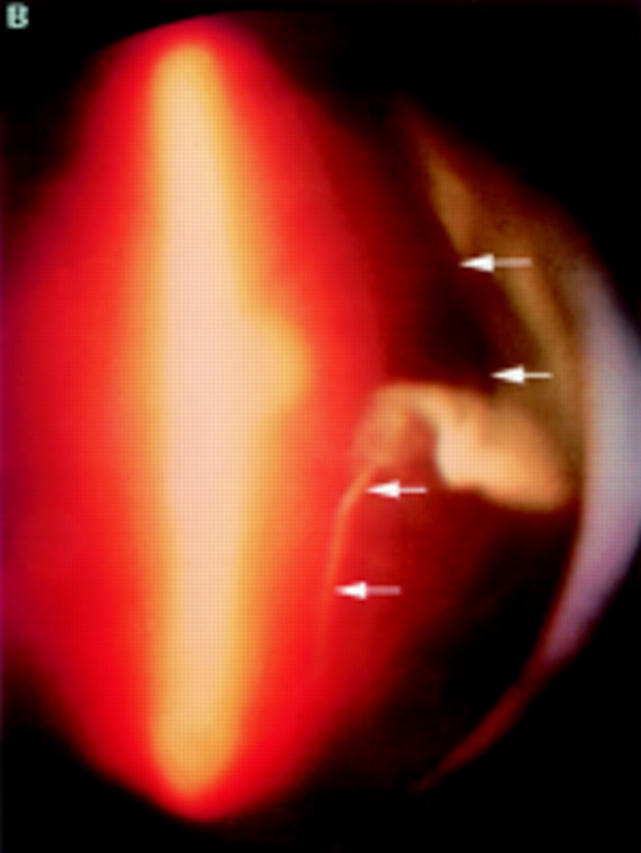

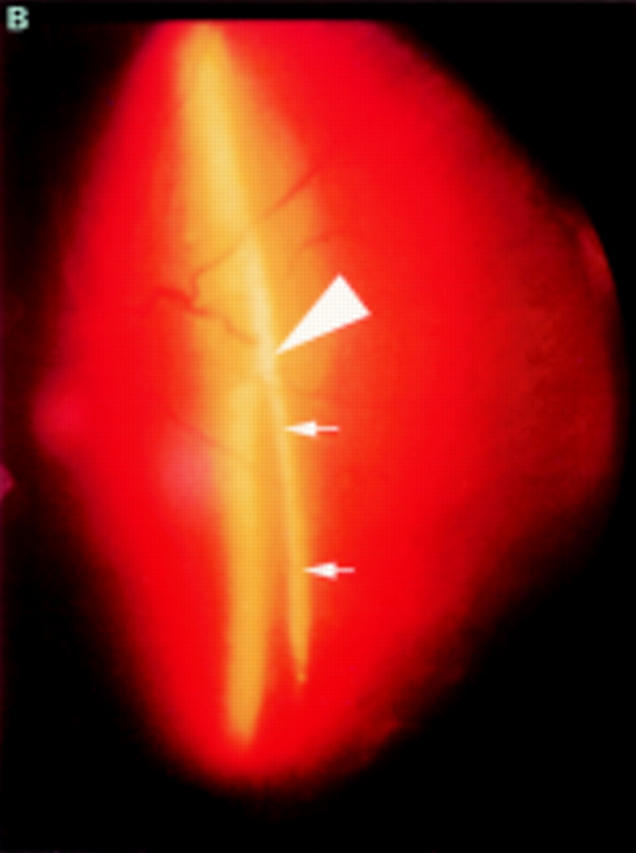

Figure 3 .

(A) Schematic sketch of partial posterior vitreous detachment (PVD) with a thickened posterior vitreous cortex (TPVC), which exhibits minimal movement with ocular movement. (B) In a patient with proliferative diabetic retinopathy, the fundus examination by indirect ophthalmoscopy revealed tractional retinal detachment. Biomicroscopic vitreous examination revealed vitreous traction upon the detached retina (arrowhead) with a condensed posterior vitreous cortex (arrows). This case was classified as partial PVD with TPVC.

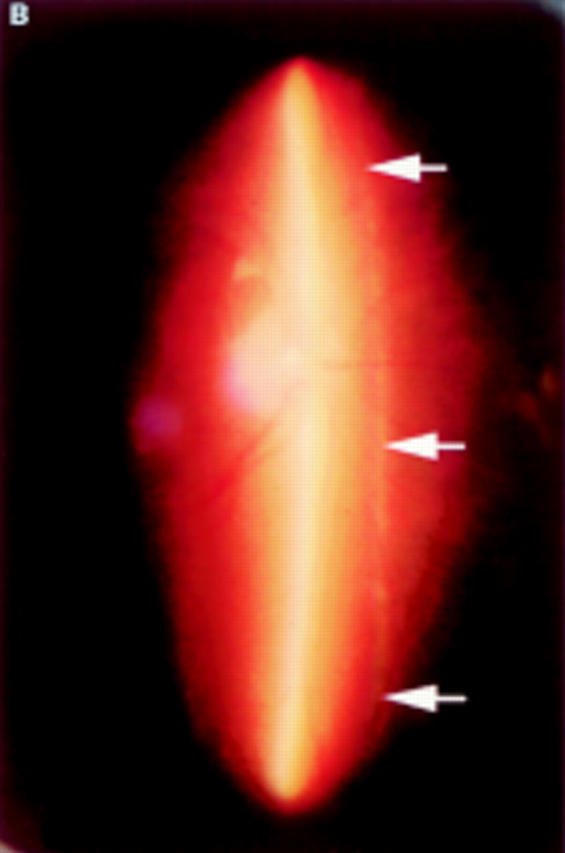

Figure 4 .

(A) Schematic sketch of partial posterior vitreous detachment (PVD) without a thickened posterior vitreous cortex (TPVC), which exhibits some mobility with ocular movement. (B) In a patient who complained of flashes in his right eye, the fundus examination by indirect ophthalmoscopy did not reveal retinal disease. The biomicroscopic vitreous examination showed localised PVD in the upper quadrants of the right eye. The vitreous gel was moderately liquefied, and with ocular movement, the posterior vitreous cortex (arrows) was not condensed and had a smooth, wavy motion. This case was classified as partial PVD without TPVC.

Figure 5 .

(A) Schematic sketch of another type of partial posterior vitreous detachment (PVD) without a thickened posterior vitreous cortex (TPVC). The vitreous gel was attached to the macular area through a round defect in the posterior vitreous cortex. (B) In a patient who complained of floaters in his visual field, the fundus examination by indirect ophthalmoscopy did not reveal retinal disease. The biomicroscopic vitreous examination revealed complete PVD except at the macular area. The vitreous gel remained attached to the macular area through a round defect in the posterior vitreous cortex. Upon ocular movement, the posterior vitreous cortex (arrows) was not condensed and had a smooth, wavy motion. This case also was classified as partial PVD without TPVC.

Selected References

These references are in PubMed. This may not be the complete list of references from this article.

- Akiba J., Kado M., Kakehashi A., Trempe C. L. Role of the vitreous in posterior segment neovascularization in central retinal vein occlusion. Ophthalmic Surg. 1991 Sep;22(9):498–502. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Akiba J., Kakehashi A., Arzabe C. W., Trempe C. L. Fellow eyes in idiopathic macular hole cases. Ophthalmic Surg. 1992 Sep;23(9):594–597. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Akiba J., Kakehashi A., Ueno N., Tano Y., Chakrabarti B. Serum-induced collagen gel contraction. Graefes Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol. 1995 Jul;233(7):430–434. doi: 10.1007/BF00180947. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Akiba J., Ueno N., Chakrabarti B. Molecular mechanisms of posterior vitreous detachment. Graefes Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol. 1993 Jul;231(7):408–412. doi: 10.1007/BF00919650. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Akiba J., Yoshida A., Trempe C. L. Risk of developing a macular hole. Arch Ophthalmol. 1990 Aug;108(8):1088–1090. doi: 10.1001/archopht.1990.01070100044031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chattopadhyay D., Akiba J., Ueno N., Chakrabarti B. Metal ion catalyzed liquefaction of vitreous by ascorbic acid: role of radicals and radical ions. Ophthalmic Res. 1992;24(1):1–7. doi: 10.1159/000267137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davis M. D. Vitreous contraction in proliferative diabetic retinopathy. Arch Ophthalmol. 1965 Dec;74(6):741–751. doi: 10.1001/archopht.1965.00970040743003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eisner G. Zur Anatomie des Glaskörpers. Albrecht Von Graefes Arch Klin Exp Ophthalmol. 1975;193(1):33–56. doi: 10.1007/BF00410525. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Faulborn J., Bowald S. Microproliferations in proliferative diabetic retinopathy and their relationship to the vitreous: corresponding light and electron microscopic studies. Graefes Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol. 1985;223(3):130–138. doi: 10.1007/BF02148888. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gass J. D. Idiopathic senile macular hole. Its early stages and pathogenesis. Arch Ophthalmol. 1988 May;106(5):629–639. doi: 10.1001/archopht.1988.01060130683026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hirokawa H., Jalkh A. E., Takahashi M., Takahashi M., Trempe C. L., Schepens C. L. Role of the vitreous in idiopathic preretinal macular fibrosis. Am J Ophthalmol. 1986 Feb 15;101(2):166–169. doi: 10.1016/0002-9394(86)90589-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jaffe N. S. Vitreous traction at the posterior pole of the fundus due to alterations in the vitreous posterior. Trans Am Acad Ophthalmol Otolaryngol. 1967 Jul-Aug;71(4):642–652. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jalkh A., Takahashi M., Topilow H. W., Trempe C. L., McMeel J. W. Prognostic value of vitreous findings in diabetic retinopathy. Arch Ophthalmol. 1982 Mar;100(3):432–434. doi: 10.1001/archopht.1982.01030030434009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kakehashi A., Akiba J., Trempe C. L. Vitreous photography with a +90-diopter double aspheric preset lens vs the El Bayadi-Kajiura preset lens. Arch Ophthalmol. 1991 Jul;109(7):962–965. doi: 10.1001/archopht.1991.01080070074038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kakehashi A., Akiba J., Ueno N., Chakrabarti B. Evidence for singlet oxygen-induced cross-links and aggregation of collagen. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1993 Nov 15;196(3):1440–1446. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1993.2413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kakehashi A., Ishiko S., Konno S., Akiba J., Kado M., Yoshida A. Observing the posterior vitreous by means of the scanning laser ophthalmoscope. Arch Ophthalmol. 1995 May;113(5):558–560. doi: 10.1001/archopht.1995.01100050020015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kakehashi A., Schepens C. L., Trempe C. L. Vitreomacular observations. I. Vitreomacular adhesion and hole in the premacular hyaloid. Ophthalmology. 1994 Sep;101(9):1515–1521. doi: 10.1016/s0161-6420(94)31140-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kakehashi A., Ueno N., Chakrabarti B. Molecular mechanisms of photochemically induced posterior vitreous detachment. Ophthalmic Res. 1994;26(1):51–59. doi: 10.1159/000267374. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kohno T., Sorgente N., Ishibashi T., Goodnight R., Ryan S. J. Immunofluorescent studies of fibronectin and laminin in the human eye. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 1987 Mar;28(3):506–514. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Larsson L., Osterlin S. Posterior vitreous detachment. A combined clinical and physiochemical study. Graefes Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol. 1985;223(2):92–95. doi: 10.1007/BF02150952. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sebag J. Abnormalities of human vitreous structure in diabetes. Graefes Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol. 1993 May;231(5):257–260. doi: 10.1007/BF00919101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sebag J. Age-related differences in the human vitreoretinal interface. Arch Ophthalmol. 1991 Jul;109(7):966–971. doi: 10.1001/archopht.1991.01080070078039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sebag J., Balazs E. A. Human vitreous fibres and vitreoretinal disease. Trans Ophthalmol Soc U K. 1985;104(Pt 2):123–128. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sebag J., Balazs E. A. Pathogenesis of cystoid macular edema: an anatomic consideration of vitreoretinal adhesions. Surv Ophthalmol. 1984 May;28 (Suppl):493–498. doi: 10.1016/0039-6257(84)90231-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sebag J., Buckingham B., Charles M. A., Reiser K. Biochemical abnormalities in vitreous of humans with proliferative diabetic retinopathy. Arch Ophthalmol. 1992 Oct;110(10):1472–1476. doi: 10.1001/archopht.1992.01080220134035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sebag J., Nie S., Reiser K., Charles M. A., Yu N. T. Raman spectroscopy of human vitreous in proliferative diabetic retinopathy. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 1994 Jun;35(7):2976–2980. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takahashi M., Trempe C. L., Maguire K., McMeel J. W. Vitreoretinal relationship in diabetic retinopathy. A biomicroscopic evaluation. Arch Ophthalmol. 1981 Feb;99(2):241–245. doi: 10.1001/archopht.1981.03930010243003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takahashi M., Trempe C. L., Schepens C. L. Biomicroscopic evaluation and photography of posterior vitreous detachment. Arch Ophthalmol. 1980 Apr;98(4):665–668. doi: 10.1001/archopht.1980.01020030659002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tolentino F. I., Lee P. F., Schepens C. L. Biomicroscopic study of vitreous cavity in diabetic retinopathy. Arch Ophthalmol. 1966 Feb;75(2):238–246. doi: 10.1001/archopht.1966.00970050240018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ueno N., Chakrabarti B. Liquefaction of human vitreous in model aphakic eyes by 300-nm UV photolysis: monitoring liquefaction by fluorescence. Curr Eye Res. 1990 May;9(5):487–492. doi: 10.3109/02713689008999614. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ueno N., Sebag J., Hirokawa H., Chakrabarti B. Effects of visible-light irradiation on vitreous structure in the presence of a photosensitizer. Exp Eye Res. 1987 Jun;44(6):863–870. doi: 10.1016/s0014-4835(87)80048-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]