Abstract

AIMS/BACKGROUND—In adult tissues the expression of tenascin-cytotactin (TN-C), an extracellular matrix glycoprotein, is limited to tumours and regions of continuous renewal. It is also transiently expressed in cutaneous and corneal wound healing. There are limited data regarding its expression in inflammation and scarring of the adult human cornea. In this study, TN-C expression patterns in normal, inflamed, and scarred human corneas have been examined. METHODS—Penetrating keratoplasty specimens were selected from cases of herpes simplex keratitis, herpes zoster ophthalmicus, rheumatoid arthritis ulceration, bacterial keratitis, rosacea keratitis, interstitial keratitis, and previous surgery so as to encompass varying degrees of active and chronic inflammation and scarring. TN-C in these and in normal corneas was immunodetected using TN2, a monoclonal antibody to human TN-C. RESULTS—There was no TN2 immunopositivity in normal corneas except at the corneoscleral interface. In pathological corneas, TN2 immunopositivity was localised in and around regions of active inflammation, fibrosis, and neovascularisation. TN2 positivity was less in acute inflammation than in active chronic inflammation. Mature, avascular scar tissue and epithelial downgrowth were TN2 negative. CONCLUSION—These results indicate that in the adult human cornea, TN-C expression is induced in regions of inflammation, fibrosis, and neovascularisation, but that expression is absent in mature, avascular scar tissue. This suggests a role for this glycoprotein in inflammation, healing, and extracellular matrix reorganisation of the cornea.

Full Text

The Full Text of this article is available as a PDF (191.5 KB).

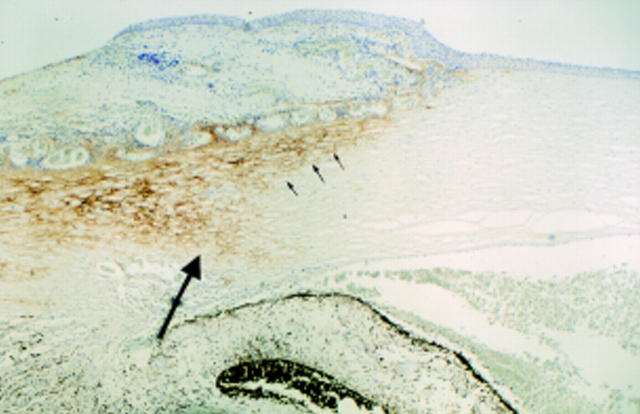

Figure 1 .

Normal cornea and corneoscleral interface. There is TN2 immunopositivity of the sclera (small arrows) including the scleral spur (large arrow). Corneal tissue is TN2 immunonegative (× 18).

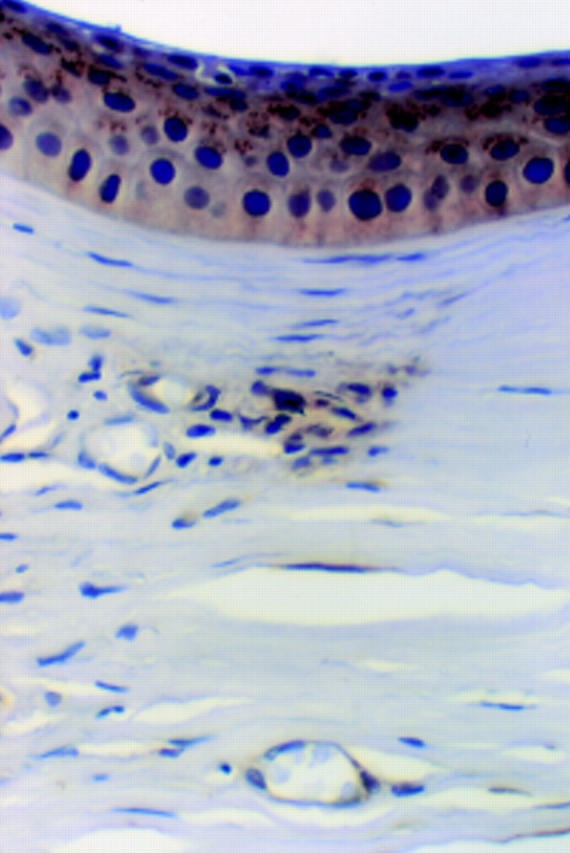

Figure 2 .

Bacterial keratitis, with ulcer and stromal abscess. Strong TN2 immunopositivity in and around the edges of the acutely inflamed tissue. The ulcer, epithelium, and stroma immediately adjacent are negative. There is also subepithelial TN2 immunopositivity in an area of epithelial lifting from oedematous stroma (small arrows) (× 38).

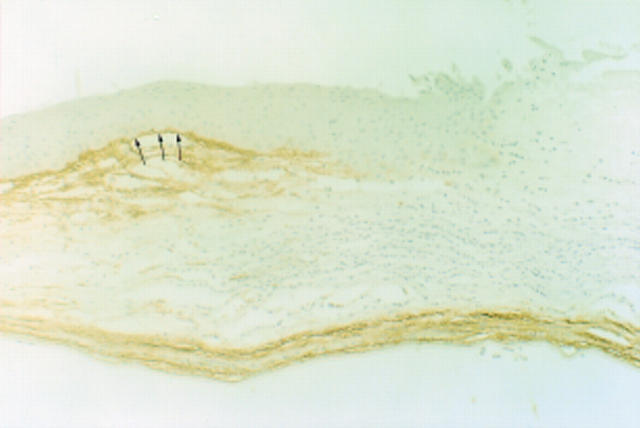

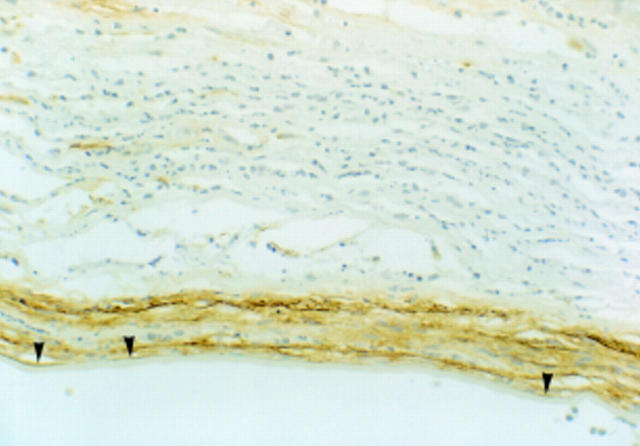

Figure 3 .

Bacterial keratitis, higher magnification. Occasional TN2 positive keratocytes are seen in the acutely inflamed area. However, the strongest TN2 immunoreaction is in the posterior stroma where there is a chronic inflammatory cell infiltrate, rather than in the acutely inflamed tissue of mid stroma. The chronic inflammatory cells are negative, but the stromal tissue is positive. Note that Descemet's membrane is negative, but there is a band of TN2 immunopositivity at the interface between posterior stroma and Descemet's membrane (arrowheads). Endothelium has been lost from this cornea (× 185).

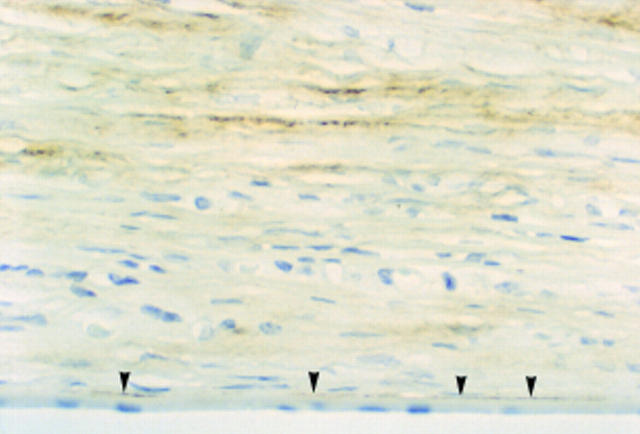

Figure 4 .

Herpes simplex keratitis cornea. There is stromal TN2 immunopositivity associated with chronic inflammation in the posterior stroma. Inflammatory cells are negative. Note that, as in Figure 3, there is also focal positivity at the interface between posterior stroma and Descement's membrane (arrowheads). Endothelium is intact (× 370).

Figure 5 .

Rheumatoid perforation with an area of epithelium bridging a stromal defect. There is diffuse, extracellular, stromal TN2 immunopositivity around the defect. The small amount of subepithelial tissue remaining beneath the undermined epithelium is also strongly positive (small arrows). Iris pigment (IP) is present as discrete deposits in the posterior stroma below and adjacent to the perforation. Very few inflammatory cells are present (× 38).

Figure 6 .

Previous surgery. There is patchy chronic inflammation and vascularisation. TN2 immunopositivity is present in the stroma where there is an aggregate of chronic inflammatory cells. Here, occasional lymphocytes have cytoplasmic membrane staining. Elsewhere, there is cytoplasmic labelling of some vascular endothelial cells. There is also granular cytoplasmic staining of epithelial cells overlying this area (× 450, oil immersion).

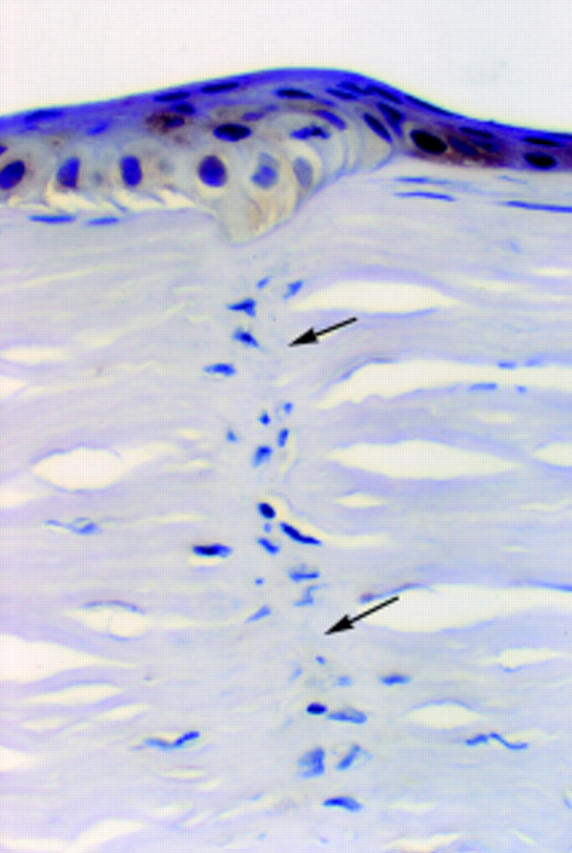

Figure 7 .

Healed 2 year old surgical incision. There is minimal fibroblastic reaction and no vascularisation or inflammation. TN2 immunoreaction is negative in the mature scar tissue (arrows). There is faint granular TN2 immunopositivity in the epithelium above the scar (× 450, oil immersion).

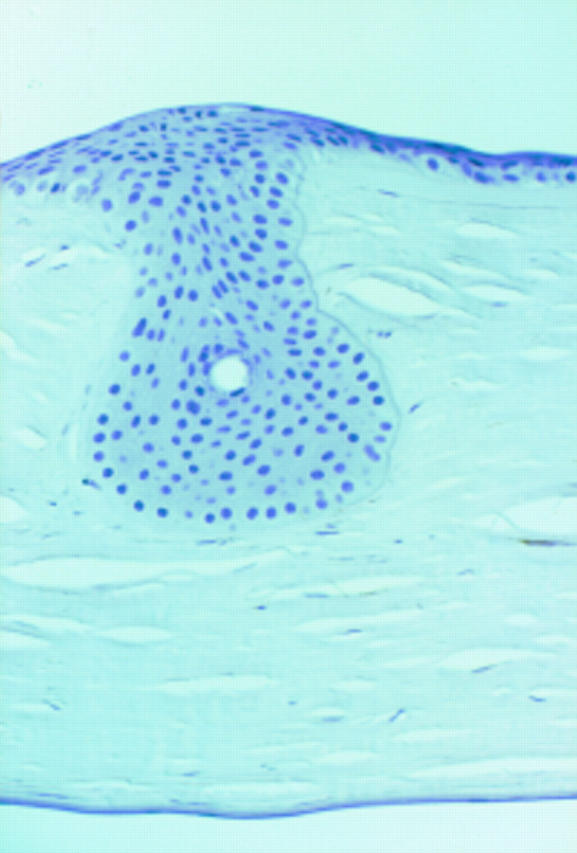

Figure 8 .

Epithelial downgrowth that fills a previous relaxing incision. TN2 immunoreaction is negative in both stroma and epithelium (× 180, differential interference contrast (DIC)).

Selected References

These references are in PubMed. This may not be the complete list of references from this article.

- Balza E., Siri A., Ponassi M., Caocci F., Linnala A., Virtanen I., Zardi L. Production and characterization of monoclonal antibodies specific for different epitopes of human tenascin. FEBS Lett. 1993 Oct 11;332(1-2):39–43. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(93)80479-e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Betz P., Nerlich A., Tübel J., Penning R., Eisenmenger W. Localization of tenascin in human skin wounds--an immunohistochemical study. Int J Legal Med. 1993;105(6):325–328. doi: 10.1007/BF01222116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bourdon M. A., Wikstrand C. J., Furthmayr H., Matthews T. J., Bigner D. D. Human glioma-mesenchymal extracellular matrix antigen defined by monoclonal antibody. Cancer Res. 1983 Jun;43(6):2796–2805. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Braun T., Rudnicki M. A., Arnold H. H., Jaenisch R. Targeted inactivation of the muscle regulatory gene Myf-5 results in abnormal rib development and perinatal death. Cell. 1992 Oct 30;71(3):369–382. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(92)90507-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brookfield J. Can genes be truly redundant? Curr Biol. 1992 Oct;2(10):553–554. doi: 10.1016/0960-9822(92)90036-a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Canfield A. E., Schor A. M. Evidence that tenascin and thrombospondin-1 modulate sprouting of endothelial cells. J Cell Sci. 1995 Feb;108(Pt 2):797–809. doi: 10.1242/jcs.108.2.797. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chiquet-Ehrismann R. Anti-adhesive molecules of the extracellular matrix. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 1991 Oct;3(5):800–804. doi: 10.1016/0955-0674(91)90053-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chiquet-Ehrismann R., Hagios C., Matsumoto K. The tenascin gene family. Perspect Dev Neurobiol. 1994;2(1):3–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chiquet-Ehrismann R., Mackie E. J., Pearson C. A., Sakakura T. Tenascin: an extracellular matrix protein involved in tissue interactions during fetal development and oncogenesis. Cell. 1986 Oct 10;47(1):131–139. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(86)90374-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crossin K. L. Cytotactin binding: inhibition of stimulated proliferation and intracellular alkalinization in fibroblasts. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1991 Dec 15;88(24):11403–11407. doi: 10.1073/pnas.88.24.11403. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- End P., Panayotou G., Entwistle A., Waterfield M. D., Chiquet M. Tenascin: a modulator of cell growth. Eur J Biochem. 1992 Nov 1;209(3):1041–1051. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1992.tb17380.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Erickson H. P., Bourdon M. A. Tenascin: an extracellular matrix protein prominent in specialized embryonic tissues and tumors. Annu Rev Cell Biol. 1989;5:71–92. doi: 10.1146/annurev.cb.05.110189.000443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Erickson H. P., Inglesias J. L. A six-armed oligomer isolated from cell surface fibronectin preparations. Nature. 1984 Sep 20;311(5983):267–269. doi: 10.1038/311267a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grumet M., Hoffman S., Crossin K. L., Edelman G. M. Cytotactin, an extracellular matrix protein of neural and non-neural tissues that mediates glia-neuron interaction. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1985 Dec;82(23):8075–8079. doi: 10.1073/pnas.82.23.8075. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hemesath T. J., Marton L. S., Stefansson K. Inhibition of T cell activation by the extracellular matrix protein tenascin. J Immunol. 1994 Jun 1;152(11):5199–5207. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joshi P., Chung C. Y., Aukhil I., Erickson H. P. Endothelial cells adhere to the RGD domain and the fibrinogen-like terminal knob of tenascin. J Cell Sci. 1993 Sep;106(Pt 1):389–400. doi: 10.1242/jcs.106.1.389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joyner A. L., Herrup K., Auerbach B. A., Davis C. A., Rossant J. Subtle cerebellar phenotype in mice homozygous for a targeted deletion of the En-2 homeobox. Science. 1991 Mar 8;251(4998):1239–1243. doi: 10.1126/science.1672471. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaplony A., Zimmermann D. R., Fischer R. W., Imhof B. A., Odermatt B. F., Winterhalter K. H., Vaughan L. Tenascin Mr 220,000 isoform expression correlates with corneal cell migration. Development. 1991 Jun;112(2):605–614. doi: 10.1242/dev.112.2.605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kruse J., Keilhauer G., Faissner A., Timpl R., Schachner M. The J1 glycoprotein--a novel nervous system cell adhesion molecule of the L2/HNK-1 family. Nature. 1985 Jul 11;316(6024):146–148. doi: 10.1038/316146a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Latvala T., Tervo K., Mustonen R., Tervo T. Expression of cellular fibronectin and tenascin in the rabbit cornea after excimer laser photorefractive keratectomy: a 12 month study. Br J Ophthalmol. 1995 Jan;79(1):65–69. doi: 10.1136/bjo.79.1.65. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mackie E. J., Halfter W., Liverani D. Induction of tenascin in healing wounds. J Cell Biol. 1988 Dec;107(6 Pt 2):2757–2767. doi: 10.1083/jcb.107.6.2757. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rothe J., Lesslauer W., Lötscher H., Lang Y., Koebel P., Köntgen F., Althage A., Zinkernagel R., Steinmetz M., Bluethmann H. Mice lacking the tumour necrosis factor receptor 1 are resistant to TNF-mediated toxicity but highly susceptible to infection by Listeria monocytogenes. Nature. 1993 Aug 26;364(6440):798–802. doi: 10.1038/364798a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rudnicki M. A., Braun T., Hinuma S., Jaenisch R. Inactivation of MyoD in mice leads to up-regulation of the myogenic HLH gene Myf-5 and results in apparently normal muscle development. Cell. 1992 Oct 30;71(3):383–390. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(92)90508-a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rüegg C. R., Chiquet-Ehrismann R., Alkan S. S. Tenascin, an extracellular matrix protein, exerts immunomodulatory activities. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1989 Oct;86(19):7437–7441. doi: 10.1073/pnas.86.19.7437. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saga Y., Yagi T., Ikawa Y., Sakakura T., Aizawa S. Mice develop normally without tenascin. Genes Dev. 1992 Oct;6(10):1821–1831. doi: 10.1101/gad.6.10.1821. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sakakura T., Kusano I. Tenascin in tissue perturbation repair. Acta Pathol Jpn. 1991 Apr;41(4):247–258. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1827.1991.tb03352.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schenk S., Bruckner-Tuderman L., Chiquet-Ehrismann R. Dermo-epidermal separation is associated with induced tenascin expression in human skin. Br J Dermatol. 1995 Jul;133(1):13–22. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.1995.tb02486.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siri A., Carnemolla B., Saginati M., Leprini A., Casari G., Baralle F., Zardi L. Human tenascin: primary structure, pre-mRNA splicing patterns and localization of the epitopes recognized by two monoclonal antibodies. Nucleic Acids Res. 1991 Feb 11;19(3):525–531. doi: 10.1093/nar/19.3.525. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smithies O. Animal models of human genetic diseases. Trends Genet. 1993 Apr;9(4):112–116. doi: 10.1016/0168-9525(93)90204-u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spring J., Beck K., Chiquet-Ehrismann R. Two contrary functions of tenascin: dissection of the active sites by recombinant tenascin fragments. Cell. 1989 Oct 20;59(2):325–334. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(89)90294-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sriramarao P., Mendler M., Bourdon M. A. Endothelial cell attachment and spreading on human tenascin is mediated by alpha 2 beta 1 and alpha v beta 3 integrins. J Cell Sci. 1993 Aug;105(Pt 4):1001–1012. doi: 10.1242/jcs.105.4.1001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tervo K., van Setten G. B., Beuerman R. W., Virtanen I., Tarkkanen A., Tervo T. Expression of tenascin and cellular fibronectin in the rabbit cornea after anterior keratectomy. Immunohistochemical study of wound healing dynamics. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 1991 Oct;32(11):2912–2918. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tervo T., van Setten G. B., Lehto I., Tervo K., Tarkkanen A., Virtanen I. Immunohistochemical demonstration of tenascin in the normal human limbus with special reference to trabeculectomy. Ophthalmic Res. 1990;22(2):128–133. doi: 10.1159/000267012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tremble P., Chiquet-Ehrismann R., Werb Z. The extracellular matrix ligands fibronectin and tenascin collaborate in regulating collagenase gene expression in fibroblasts. Mol Biol Cell. 1994 Apr;5(4):439–453. doi: 10.1091/mbc.5.4.439. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Uusitalo M. Immunohistochemical localization of chondroitin sulfate proteoglycan and tenascin in the human eye compared with the HNK-1 epitope. Graefes Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol. 1994 Nov;232(11):657–665. doi: 10.1007/BF00171380. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wallace W. A., Howie S. E., Lamb D., Salter D. M. Tenascin immunoreactivity in cryptogenic fibrosing alveolitis. J Pathol. 1995 Apr;175(4):415–420. doi: 10.1002/path.1711750409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zagzag D., Friedlander D. R., Dosik J., Chikramane S., Chan W., Greco M. A., Allen J. C., Dorovini-Zis K., Grumet M. Tenascin-C expression by angiogenic vessels in human astrocytomas and by human brain endothelial cells in vitro. Cancer Res. 1996 Jan 1;56(1):182–189. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zagzag D., Friedlander D. R., Miller D. C., Dosik J., Cangiarella J., Kostianovsky M., Cohen H., Grumet M., Greco M. A. Tenascin expression in astrocytomas correlates with angiogenesis. Cancer Res. 1995 Feb 15;55(4):907–914. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Setten G. B., Koch J. W., Tervo K., Lang G. K., Tervo T., Naumann G. O., Kolkmeier J., Virtanen I., Tarkkanen A. Expression of tenascin and fibronectin in the rabbit cornea after excimer laser surgery. Graefes Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol. 1992;230(2):178–183. doi: 10.1007/BF00164660. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]