Abstract

AIMS—To determine the quantitative relation between the major risk factors for microbial keratitis of previous ocular surface disease and contact lens wear and central and peripheral infiltration, often associated with ulceration, in order to establish a rational chemotherapeutic management algorithm. METHODS—Data from 55 patients were collected over a 10 month period. All cases of presumed microbial keratitis where corneal scrapes had been subjected to microbiological examination were included. Risk factor data and laboratory outcome were recorded. Antimicrobial regimens used to treat each patient were documented. RESULTS—57 episodes of presumed microbial keratitis were identified from 55 patients, 24 male and 31 female. There were 30 central infiltrates and 27 peripheral infiltrates of which 28 were culture positive (73% of central infiltrates, 22% of peripheral infiltrates). 26 patients had worn contact lenses of whom 12 had culture positive scrapes (9/14 for central infiltrates, 3/12 for peripheral infiltrates). 31 patients had an ocular surface disease of whom five previous herpes simplex virus keratitis patients developed secondary bacterial infection. Anterior chamber activity and an infiltrate size ⩾ 4 mm2 were more common with culture positive central infiltrates than peripheral infiltrates (χ2 test = 11.98, p<0.001). CONCLUSIONS—Predisposing factors for "presumed" microbial keratitis, either central or peripheral, were: ocular surface disease (26/57 = 45.6%), contact lens wear (26/57 = 45.6%), and previous trauma (5/57 = 8.8%). Larger ulceration (⩾4 mm2) with inflammation was more often associated with positive culture results for central infiltration. None of these four variables (contact lens wear, ocular surface disease, ulcer size, anterior chamber activity) were of intrinsic value in predicting if a peripheral infiltrate would yield identifiable micro-organisms. Successful management of presumed microbial keratitis is aided by a logical approach to therapy, with the use of a defined algorithm of first and second line broad spectrum antimicrobials, for application at each stage of the investigative and treatment process considering central and peripheral infiltration separately. Keywords: ulcerative keratitis; antimicrobials; ulcers

Full Text

The Full Text of this article is available as a PDF (212.7 KB).

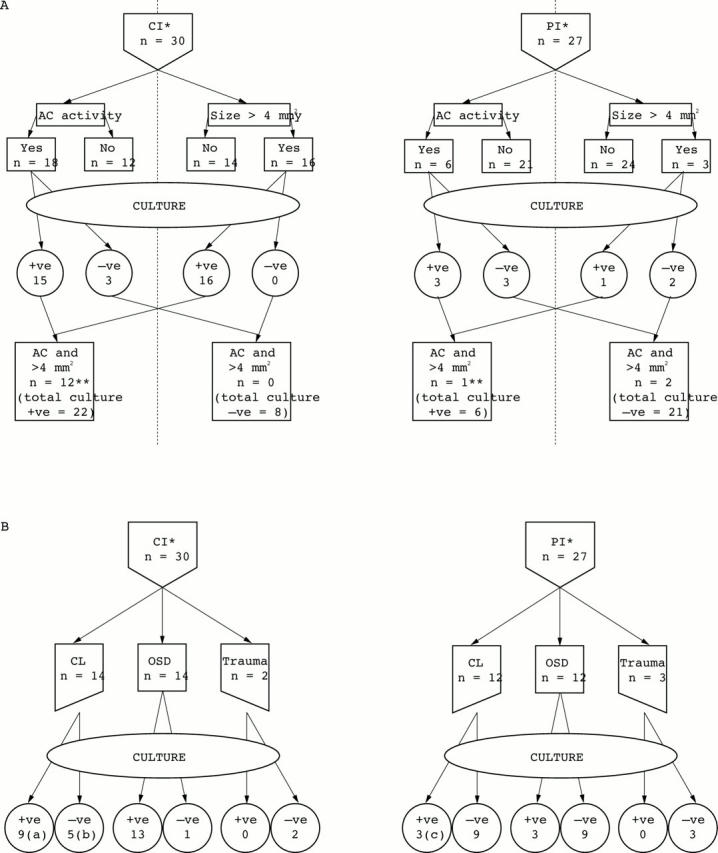

Figure 1 .

(A) Clinical signs: predictors of a positive culture result. (B) Predisposing risk factors for microbial keratitis.*CI = central infiltration; PI = peripheral infiltration. OCD = ocular surface disease. **Excludes all patients with Acanthamoeba and Vahlkampfia keratitis (since no infiltrate ⩾4 mm2). (a) Three extended wear contact lenses (one congenital cataract, 0.05 years; one chronic allergic keratoconjunctivitis; one band-shaped keratopathy: former two, S pneumoniae, latter, S aureus). (b) Two presentations due to contact lens associated keratopathy (CLAK). (c) One extended wear contact lens (exposure keratopathy due to S aureus).

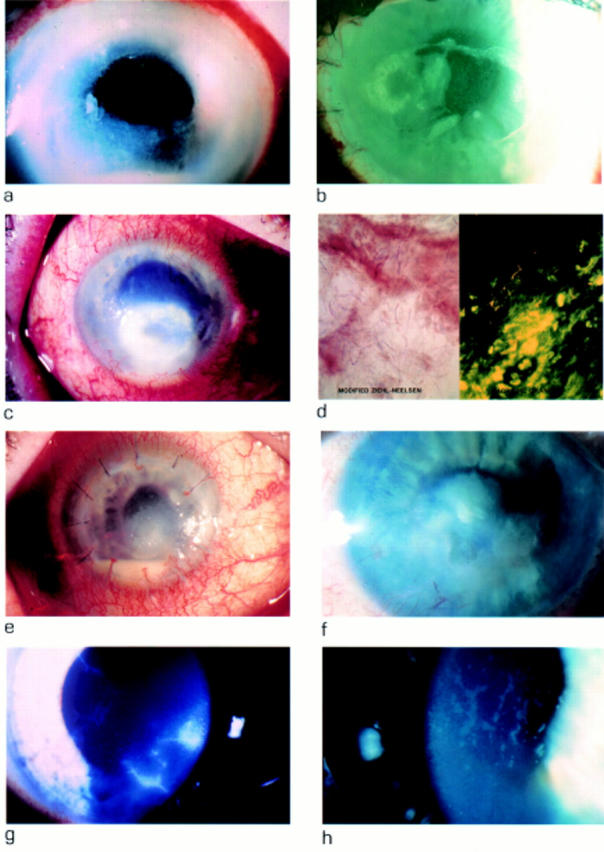

Figure 2 .

(a) Pseudomonas aeruginosa keratitis with central desmetocele. Infection from use of contaminated cosmetic eyedrops. (b) Sporotrichon keratitis in patient A, 4 months after penetrating keratoplasty. (c) Nocardia keratitis in patient with mild ocular cicatricial pemphigoid. (d) Modified Ziehl-Neelsen (left) and acridine orange (right) stains of corneal biopsy material from patient C showing presence of Nocardia species. (e) Staphylococcus aureus keratitis in patient C, 5 months after lamellar keratoplasty. (f) Acinetobacter haemolyticus keratitis in a patient with a history of severe herpes simplex keratitis and secondary corneal vascularisation. (g) Acanthamoeba keratitis in a soft contact lens wearer (FDA group 4) who used chlorine based disinfection and tap water for contact lens hygiene. (h) Contact lens associated keratitis (CLAK) in a soft contact lens wearer (FDA group 1) who used both hydrogen peroxide based disinfection and tap water for contact lens hygiene.

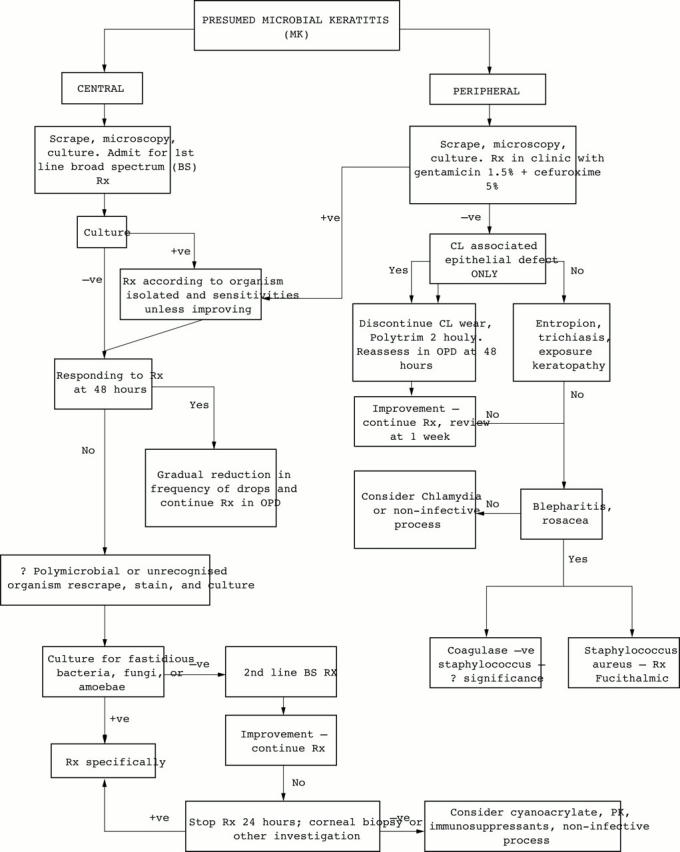

Figure 3 .

Chemotherapeutic algorithm for the management of presumed microbial keratitis.

Selected References

These references are in PubMed. This may not be the complete list of references from this article.

- Aitken D., Hay J., Kinnear F. B., Kirkness C. M., Lee W. R., Seal D. V. Amebic keratitis in a wearer of disposable contact lenses due to a mixed Vahlkampfia and Hartmannella infection. Ophthalmology. 1996 Mar;103(3):485–494. doi: 10.1016/s0161-6420(96)30667-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Allan B. D., Dart J. K. Strategies for the management of microbial keratitis. Br J Ophthalmol. 1995 Aug;79(8):777–786. doi: 10.1136/bjo.79.8.777. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aristimuño B., Nirankari V. S., Hemady R. K., Rodrigues M. M. Spontaneous ulcerative keratitis in immunocompromised patients. Am J Ophthalmol. 1993 Feb 15;115(2):202–208. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9394(14)73924-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aronson S. B., Moore T. E., Jr Corticosteroid therapy in central stromal keratitis. Am J Ophthalmol. 1969 Jun;67(6):873–896. doi: 10.1016/0002-9394(69)90082-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Asbell P., Stenson S. Ulcerative keratitis. Survey of 30 years' laboratory experience. Arch Ophthalmol. 1982 Jan;100(1):77–80. doi: 10.1001/archopht.1982.01030030079005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bates A. K., Morris R. J., Stapleton F., Minassian D. C., Dart J. K. 'Sterile' corneal infiltrates in contact lens wearers. Eye (Lond) 1989;3(Pt 6):803–810. doi: 10.1038/eye.1989.124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benson W. H., Lanier J. D. Comparison of techniques for culturing corneal ulcers. Ophthalmology. 1992 May;99(5):800–804. doi: 10.1016/s0161-6420(92)31897-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Binder P. S., Rasmussen D. M., Gordon M. Keratoconjunctivitis and soft contact lens solutions. Arch Ophthalmol. 1981 Jan;99(1):87–90. doi: 10.1001/archopht.1981.03930010089009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chander J., Sharma A. Prevalence of fungal corneal ulcers in northern India. Infection. 1994 May-Jun;22(3):207–209. doi: 10.1007/BF01716706. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clinch T. E., Palmon F. E., Robinson M. J., Cohen E. J., Barron B. A., Laibson P. R. Microbial keratitis in children. Am J Ophthalmol. 1994 Jan 15;117(1):65–71. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9394(14)73016-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cruz O. A., Sabir S. M., Capo H., Alfonso E. C. Microbial keratitis in childhood. Ophthalmology. 1993 Feb;100(2):192–196. doi: 10.1016/s0161-6420(93)31671-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dunlop A. A., Wright E. D., Howlader S. A., Nazrul I., Husain R., McClellan K., Billson F. A. Suppurative corneal ulceration in Bangladesh. A study of 142 cases examining the microbiological diagnosis, clinical and epidemiological features of bacterial and fungal keratitis. Aust N Z J Ophthalmol. 1994 May;22(2):105–110. doi: 10.1111/j.1442-9071.1994.tb00775.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ficker L., Kirkness C., McCartney A., Seal D. Microbial keratitis--the false negative. Eye (Lond) 1991;5(Pt 5):549–559. doi: 10.1038/eye.1991.97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goodall K., Brahma A., Ridgway A. Acanthamoeba keratitis: masquerading as adenoviral keratitis. Eye (Lond) 1996;10(Pt 5):643–644. doi: 10.1038/eye.1996.148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Groden L. R., Brinser J. H. Outpatient treatment of microbial corneal ulcers. Arch Ophthalmol. 1986 Jan;104(1):84–86. doi: 10.1001/archopht.1986.01050130094028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hagan M., Wright E., Newman M., Dolin P., Johnson G. Causes of suppurative keratitis in Ghana. Br J Ophthalmol. 1995 Nov;79(11):1024–1028. doi: 10.1136/bjo.79.11.1024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hay J., Kirkness C. M., Seal D. V., Wright P. Drug resistance and Acanthamoeba keratitis: the quest for alternative antiprotozoal chemotherapy. Eye (Lond) 1994;8(Pt 5):555–563. doi: 10.1038/eye.1994.137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heathcote J. G., McCartney A. C., Rice N. S., Peacock J., Seal D. V. Endophthalmitis caused by exogenous nocardial infection in a patient with Sjögren's syndrome. Can J Ophthalmol. 1990 Feb;25(1):29–33. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hemady R. K. Microbial keratitis in patients infected with the human immunodeficiency virus. Ophthalmology. 1995 Jul;102(7):1026–1030. doi: 10.1016/s0161-6420(95)30917-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holden B. A., La Hood D., Grant T., Newton-Howes J., Baleriola-Lucas C., Willcox M. D., Sweeney D. F. Gram-negative bacteria can induce contact lens related acute red eye (CLARE) responses. CLAO J. 1996 Jan;22(1):47–52. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hyndiuk R. A., Eiferman R. A., Caldwell D. R., Rosenwasser G. O., Santos C. I., Katz H. R., Badrinath S. S., Reddy M. K., Adenis J. P., Klauss V. Comparison of ciprofloxacin ophthalmic solution 0.3% to fortified tobramycin-cefazolin in treating bacterial corneal ulcers. Ciprofloxacin Bacterial Keratitis Study Group. Ophthalmology. 1996 Nov;103(11):1854–1863. doi: 10.1016/s0161-6420(96)30416-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Illingworth C. D., Cook S. D., Karabatsas C. H., Easty D. L. Acanthamoeba keratitis: risk factors and outcome. Br J Ophthalmol. 1995 Dec;79(12):1078–1082. doi: 10.1136/bjo.79.12.1078. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones D. B. Decision-making in the management of microbial keratitis. Ophthalmology. 1981 Aug;88(8):814–820. doi: 10.1016/s0161-6420(81)34943-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kennedy S. M., Devine P., Hurley C., Ooi Y. S., Collum L. M. Corneal infection associated with Hartmannella vermiformis in contact-lens wearer. Lancet. 1995 Sep 2;346(8975):637–638. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ledee D. R., Hay J., Byers T. J., Seal D. V., Kirkness C. M. Acanthamoeba griffini. Molecular characterization of a new corneal pathogen. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 1996 Mar;37(4):544–550. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee P., Green W. R. Corneal biopsy. Indications, techniques, and a report of a series of 87 cases. Ophthalmology. 1990 Jun;97(6):718–721. doi: 10.1016/s0161-6420(90)32517-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liesegang T. J., Forster R. K. Spectrum of microbial keratitis in South Florida. Am J Ophthalmol. 1980 Jul;90(1):38–47. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9394(14)75075-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin M. J., Rahman M. R., Johnson G. J., Srinivasan M., Clayton Y. M. Mycotic keratitis: susceptibility to antiseptic agents. Int Ophthalmol. 1995;19(5):299–302. doi: 10.1007/BF00130925. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McLeod S. D., DeBacker C. M., Viana M. A. Differential care of corneal ulcers in the community based on apparent severity. Ophthalmology. 1996 Mar;103(3):479–484. doi: 10.1016/s0161-6420(96)30668-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miño de Kaspar H., Zoulek G., Paredes M. E., Alborno R., Medina D., Centurion de Morinigo M., Ortiz de Fresco M., Aguero F. Mycotic keratitis in Paraguay. Mycoses. 1991 May-Jun;34(5-6):251–254. doi: 10.1111/j.1439-0507.1991.tb00653.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mondino B. J., Groden L. R. Conjunctival hyperemia and corneal infiltrates with chemically disinfected soft contact lenses. Arch Ophthalmol. 1980 Oct;98(10):1767–1770. doi: 10.1001/archopht.1980.01020040619005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O'Brien T. P., Maguire M. G., Fink N. E., Alfonso E., McDonnell P. Efficacy of ofloxacin vs cefazolin and tobramycin in the therapy for bacterial keratitis. Report from the Bacterial Keratitis Study Research Group. Arch Ophthalmol. 1995 Oct;113(10):1257–1265. doi: 10.1001/archopht.1995.01100100045026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ormerod L. D. Causation and management of microbial keratitis in subtropical Africa. Ophthalmology. 1987 Dec;94(12):1662–1668. doi: 10.1016/s0161-6420(87)33235-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perry L. D., Brinser J. H., Kolodner H. Anaerobic corneal ulcers. Ophthalmology. 1982 Jun;89(6):636–642. doi: 10.1016/s0161-6420(82)34741-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pimenides D., Steele C. F., McGhee C. N., Bryce I. G. Deep corneal stromal opacities associated with long term contact lens wear. Br J Ophthalmol. 1996 Jan;80(1):21–24. doi: 10.1136/bjo.80.1.21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pyott A., Hay J., Seal D. Acanthamoeba keratitis: first recorded case from a Palestinian patient with trachoma. Br J Ophthalmol. 1996 Sep;80(9):849–849. doi: 10.1136/bjo.80.9.849. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Radford C. F., Bacon A. S., Dart J. K., Minassian D. C. Risk factors for acanthamoeba keratitis in contact lens users: a case-control study. BMJ. 1995 Jun 17;310(6994):1567–1570. doi: 10.1136/bmj.310.6994.1567. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raizman M. Corticosteroid therapy of eye disease. Fifty years later. Arch Ophthalmol. 1996 Aug;114(8):1000–1001. doi: 10.1001/archopht.1996.01100140208016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schein O. D., Wasson P. J., Boruchoff S. A., Kenyon K. R. Microbial keratitis associated with contaminated ocular medications. Am J Ophthalmol. 1988 Apr 15;105(4):361–365. doi: 10.1016/0002-9394(88)90298-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seal D. V., Hay J., Devonshire P., Kirkness C. M. Acanthamoeba and contact lens disinfection: should chlorine be discontinued? Br J Ophthalmol. 1993 Feb;77(2):128–128. doi: 10.1136/bjo.77.2.128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seal D. V., Hay J. Risk factors for acanthamoeba keratitis. Population study is required to confirm results. BMJ. 1995 Sep 23;311(7008):808–808. doi: 10.1136/bmj.311.7008.808a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seal D., Hay J., Kirkness C., Morrell A., Booth A., Tullo A., Ridgway A., Armstrong M. Successful medical therapy of Acanthamoeba keratitis with topical chlorhexidine and propamidine. Eye (Lond) 1996;10(Pt 4):413–421. doi: 10.1038/eye.1996.92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sharma S., Srinivasan M., George C. Acanthamoeba keratitis in non-contact lens wearers. Arch Ophthalmol. 1990 May;108(5):676–678. doi: 10.1001/archopht.1990.01070070062035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stapleton F., Dart J., Minassian D. Nonulcerative complications of contact lens wear. Relative risks for different lens types. Arch Ophthalmol. 1992 Nov;110(11):1601–1606. doi: 10.1001/archopht.1992.01080230101031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stein R. M., Clinch T. E., Cohen E. J., Genvert G. I., Arentsen J. J., Laibson P. R. Infected vs sterile corneal infiltrates in contact lens wearers. Am J Ophthalmol. 1988 Jun 15;105(6):632–636. doi: 10.1016/0002-9394(88)90056-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stern G. A., Buttross M. Use of corticosteroids in combination with antimicrobial drugs in the treatment of infectious corneal disease. Ophthalmology. 1991 Jun;98(6):847–853. doi: 10.1016/s0161-6420(91)32211-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suchecki J. K., Ehlers W. H., Donshik P. C. Peripheral corneal infiltrates associated with contact lens wear. CLAO J. 1996 Jan;22(1):41–46. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wahl J. C., Katz H. R., Abrams D. A. Infectious keratitis in Baltimore. Ann Ophthalmol. 1991 Jun;23(6):234–237. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilhelmus K. R., Gee L., Hauck W. W., Kurinij N., Dawson C. R., Jones D. B., Barron B. A., Kaufman H. E., Sugar J., Hyndiuk R. A. Herpetic Eye Disease Study. A controlled trial of topical corticosteroids for herpes simplex stromal keratitis. Ophthalmology. 1994 Dec;101(12):1883–1896. doi: 10.1016/s0161-6420(94)31087-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams G., Billson F., Husain R., Howlader S. A., Islam N., McClellan K. Microbiological diagnosis of suppurative keratitis in Bangladesh. Br J Ophthalmol. 1987 Apr;71(4):315–321. doi: 10.1136/bjo.71.4.315. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]