Abstract

AIM—To demonstrate the usefulness of a recently developed technique of imaging fundus autofluorescence and to compare it with the results of fluorescein angiography in the diagnosis and staging of macular holes. METHODS—The intensity and distribution of fundus autofluorescence was studied in 51 patients with idiopathic macular holes and pseudoholes using a confocal laser scanning ophthalmoscope (cLSO) and the images were compared with those obtained by fundus fluorescein angiography. RESULTS—Autofluorescence imaging demonstrated bright fluorescence of macular holes with appearance similar to that obtained by fluorescein angiography. In contrast macular pseuodoholes showed no such autofluorescence. The attached operculum in stage 2 macular holes and the preretinal operculum in stage 3 macular holes showed focal decreased autofluorescence. The associated retinal elevation and the cuff of subretinal fluid were less fluorescent compared with the background autofluorescence of the normal fellow eyes. Following successful surgical treatment the autofluorescence of the macular holes was no longer visible. CONCLUSION—Autofluorescence imaging with the cLSO makes the assessment of macular holes possible with an accuracy comparable with that of fluorescein angiography. Being non-invasive and rapid, autofluorescence imaging may become a useful alternative to fluorescein angiography in the assessment and the differential diagnosis of full thickness macular holes. Keywords: fundus autofluorescence; macular hole; lipofuscin; retinal pigment epithelium; laser scanning ophthalmoscope

Full Text

The Full Text of this article is available as a PDF (232.6 KB).

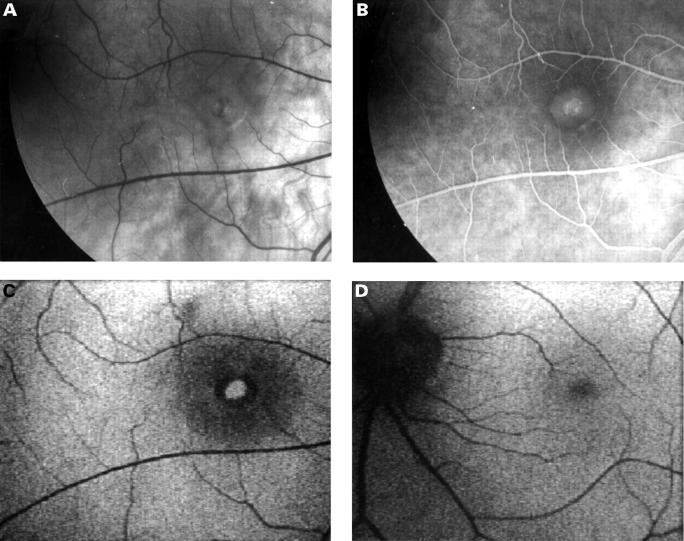

Figure 1 .

Fundus photograph of the right eye with a stage 1 full thickness macular hole (A). Note very mild hyperfluorescence in the mid phase of the fluorescein angiogram (B). Autofluorescence imaging shows an area of slightly increased fluorescence within the macular hole to the point of being equal to the autofluorescence of the surrounding parafoveal area (20° field) (C).

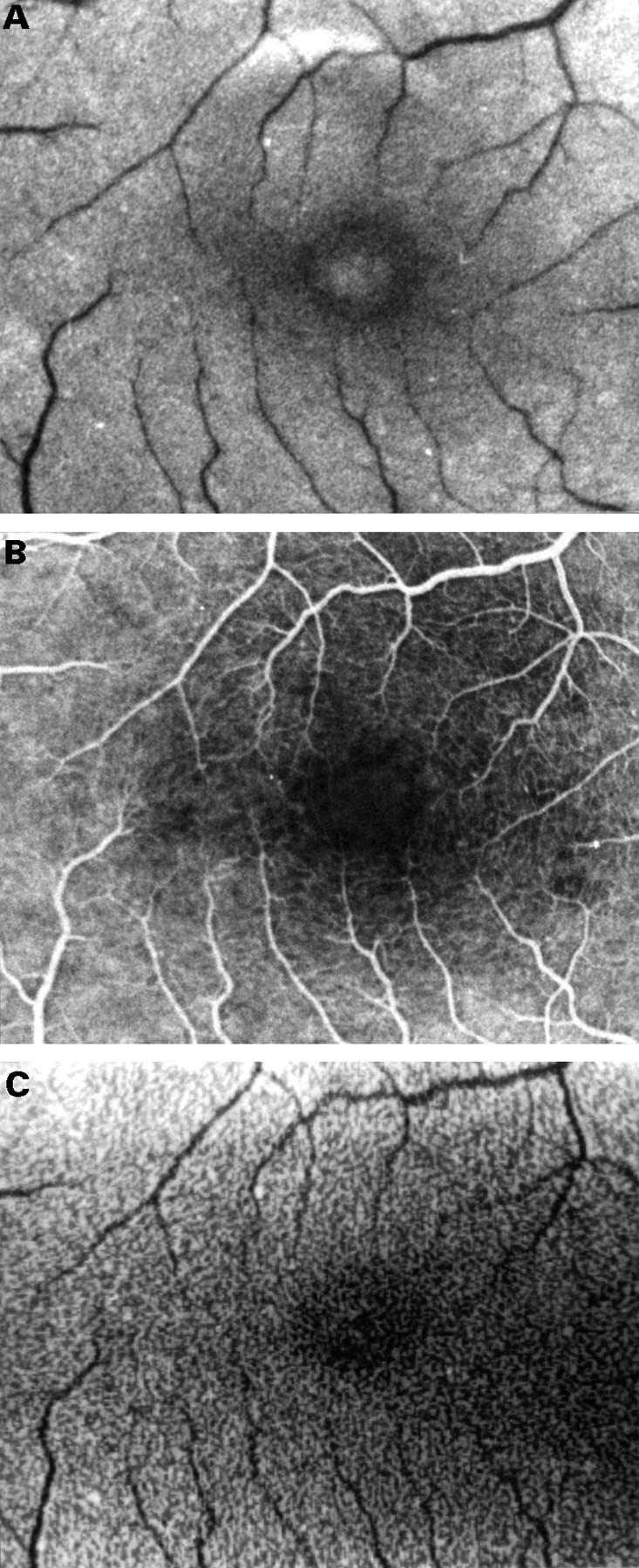

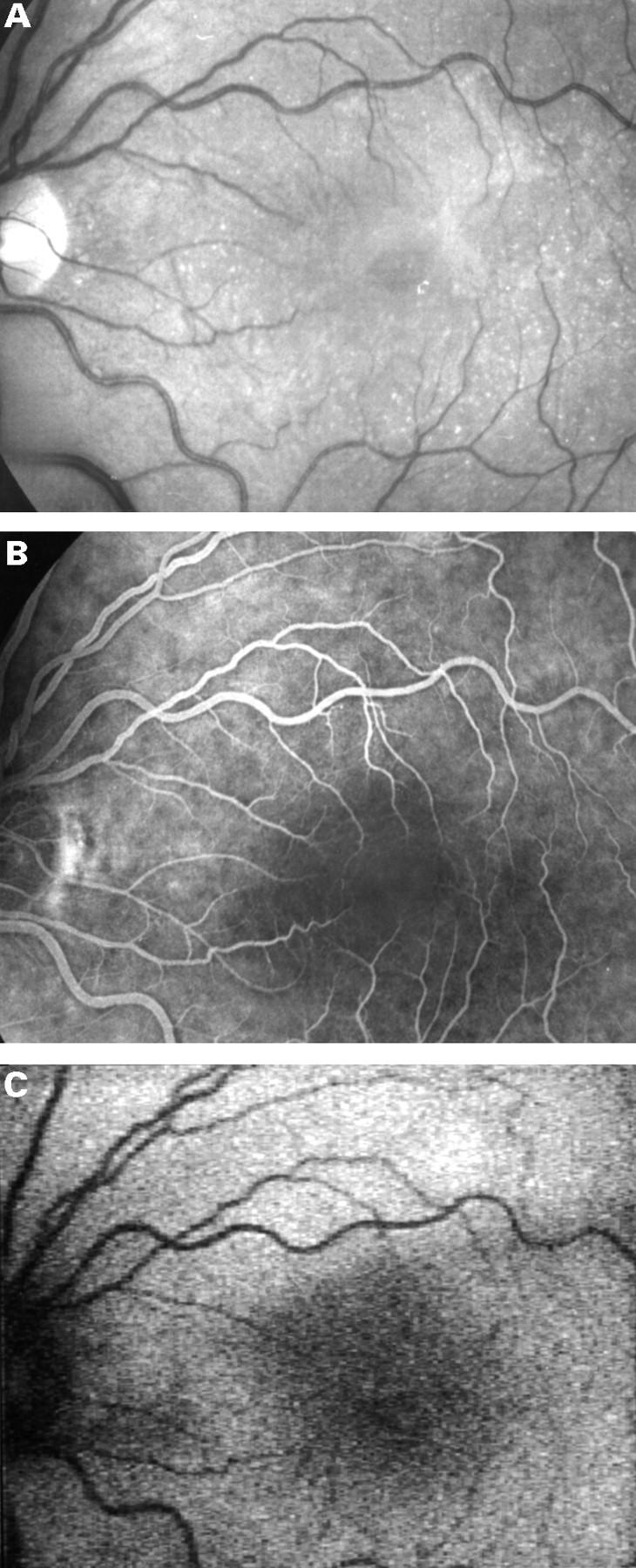

Figure 2 .

Fundus photograph of the right eye with a stage 2 full thickness macular hole (A). Fluorescein angiography shows a small window defect (B). Autofluorescence imaging shows increased fluorescence centrally. The less fluorescent zone within the macular hole in the superior-nasal part may represent a partially attached operculum (20° field) (C).

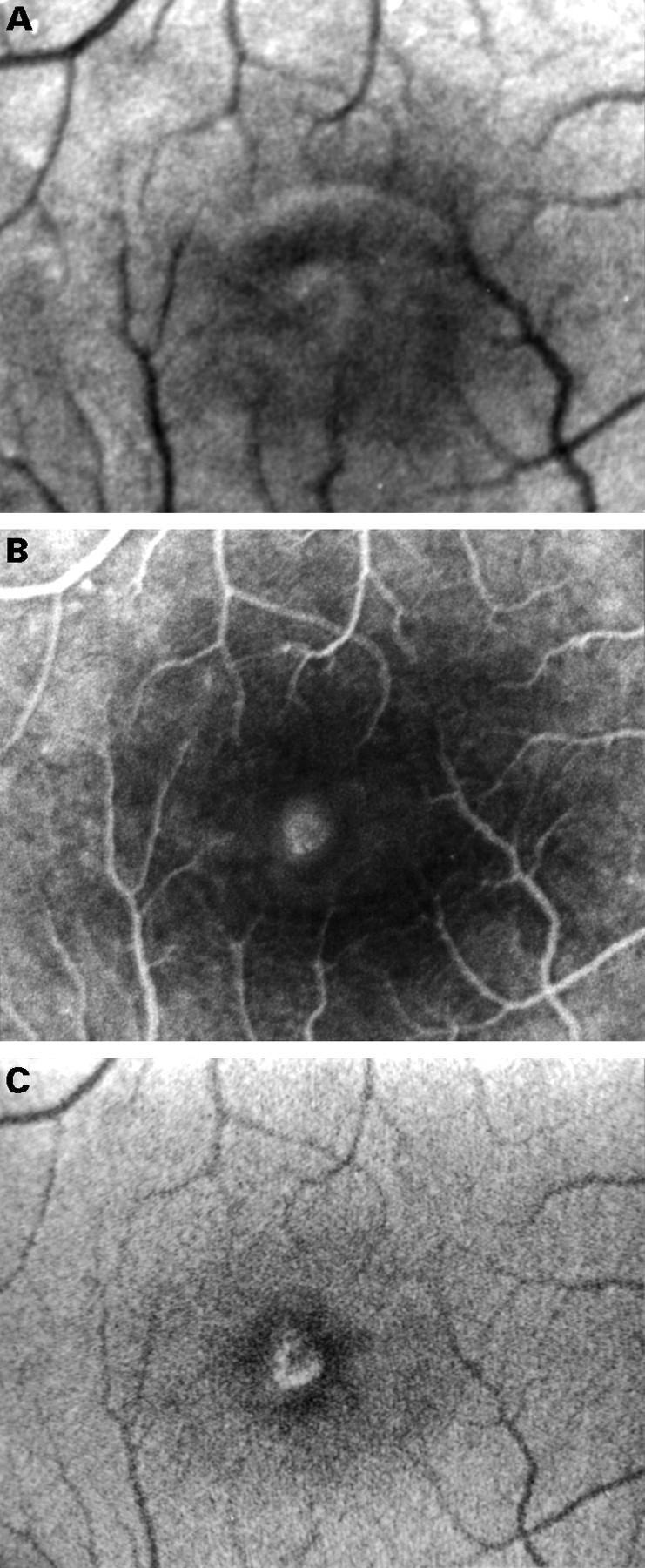

Figure 3 .

Fundus photograph and fluorescein angiogram of the right eye with a stage 4 full thickness macular hole (A, B). Autofluorescence imaging shows increased autofluorescence centrally corresponding to the macular hole and a ring of decreased autofluorescence corresponding to the cuff of subretinal fluid. The shallow subretinal fluid which extends beyond the cuff is seen as an area of decreased autofluorescence surrounding the cuff of the hole (40° field) (C). The contralateral normal eye shows even autofluorescence (D).

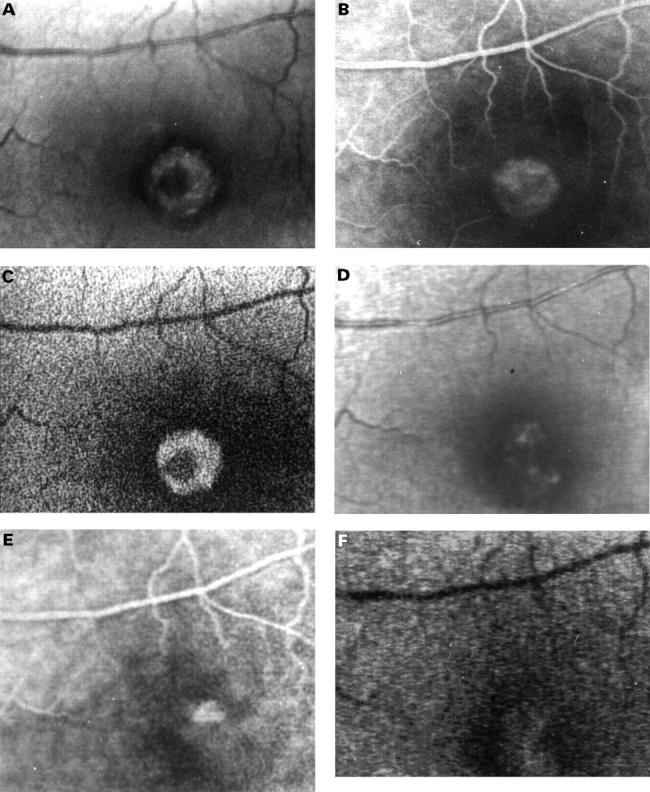

Figure 4 .

Fundus photograph and fluorescein angiogram of the right eye of a patient with a stage 3 full thickness macular hole who subsequently underwent macular hole surgery (A, B). Preoperatively autofluorescence imaging shows increased autofluorescence centrally corresponding to the macular hole and a ring of decreased autofluorescence corresponding to the cuff of subretinal fluid and to the retinal elevation which extends beyond the cuff. The operculum appears as a dark structure on autofluorescence imaging (20° field) (C). The postoperative fundus photograph and fluorescein angiogram demonstrates the closure of the macular hole though there is a small pigment epithelial defect centrally (D, E). On autofluorescence imaging the central hyperfluorescence is no longer visible, demonstrating the closure of the macular hole. The hypofluorescence corresponding to the cuff disappeared too, suggesting flattening of the neurosensory detachment (20° field) (F).

Figure 5 .

Fundus photograph of the left eye of a patient with a macular pseudohole (A). Fluorescein angiography shows no window defect (B) and autofluorescence imaging shows normal fluorescence confirming that there is no full thickness retinal defect (C).

Selected References

These references are in PubMed. This may not be the complete list of references from this article.

- Delori F. C., Dorey C. K., Staurenghi G., Arend O., Goger D. G., Weiter J. J. In vivo fluorescence of the ocular fundus exhibits retinal pigment epithelium lipofuscin characteristics. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 1995 Mar;36(3):718–729. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fish R. H., Anand R., Izbrand D. J. Macular pseudoholes. Clinical features and accuracy of diagnosis. Ophthalmology. 1992 Nov;99(11):1665–1670. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fisher Y. L., Slakter J. S., Yannuzzi L. A., Guyer D. R. A prospective natural history study and kinetic ultrasound evaluation of idiopathic macular holes. Ophthalmology. 1994 Jan;101(1):5–11. doi: 10.1016/s0161-6420(94)31356-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Funata M., Wendel R. T., de la Cruz Z., Green W. R. Clinicopathologic study of bilateral macular holes treated with pars plana vitrectomy and gas tamponade. Retina. 1992;12(4):289–298. doi: 10.1097/00006982-199212040-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gass J. D. Idiopathic senile macular hole. Its early stages and pathogenesis. Arch Ophthalmol. 1988 May;106(5):629–639. doi: 10.1001/archopht.1988.01060130683026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glaser B. M., Michels R. G., Kuppermann B. D., Sjaarda R. N., Pena R. A. Transforming growth factor-beta 2 for the treatment of full-thickness macular holes. A prospective randomized study. Ophthalmology. 1992 Jul;99(7):1162–1173. doi: 10.1016/s0161-6420(92)31837-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hee M. R., Puliafito C. A., Wong C., Duker J. S., Reichel E., Schuman J. S., Swanson E. A., Fujimoto J. G. Optical coherence tomography of macular holes. Ophthalmology. 1995 May;102(5):748–756. doi: 10.1016/s0161-6420(95)30959-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson R. N., Gass J. D. Idiopathic macular holes. Observations, stages of formation, and implications for surgical intervention. Ophthalmology. 1988 Jul;95(7):917–924. doi: 10.1016/s0161-6420(88)33075-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kelly N. E., Wendel R. T. Vitreous surgery for idiopathic macular holes. Results of a pilot study. Arch Ophthalmol. 1991 May;109(5):654–659. doi: 10.1001/archopht.1991.01080050068031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liggett P. E., Skolik D. S., Horio B., Saito Y., Alfaro V., Mieler W. Human autologous serum for the treatment of full-thickness macular holes. A preliminary study. Ophthalmology. 1995 Jul;102(7):1071–1076. doi: 10.1016/s0161-6420(95)30909-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martinez J., Smiddy W. E., Kim J., Gass J. D. Differentiating macular holes from macular pseudoholes. Am J Ophthalmol. 1994 Jun 15;117(6):762–767. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9394(14)70319-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smiddy W. E., Glaser B. M., Green W. R., Connor T. B., Jr, Roberts A. B., Lucas R., Sporn M. B. Transforming growth factor beta. A biologic chorioretinal glue. Arch Ophthalmol. 1989 Apr;107(4):577–580. doi: 10.1001/archopht.1989.01070010591036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thompson J. T., Hiner C. J., Glaser B. M., Gordon A. J., Murphy R. P., Sjaarda R. N. Fluorescein angiographic characteristics of macular holes before and after vitrectomy with transforming growth factor beta-2. Am J Ophthalmol. 1994 Mar 15;117(3):291–301. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9394(14)73135-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van de Velde F. J., Timberlake G. T., Jalkh A. E., Schepens C. L. La micropérimétrie statique avec l'ophtalmoscope à balayage laser. Ophtalmologie. 1990 May-Jun;4(3):291–294. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watzke R. C., Allen L. Subjective slitbeam sign for macular disease. Am J Ophthalmol. 1969 Sep;68(3):449–453. doi: 10.1016/0002-9394(69)90712-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wells J. A., Gregor Z. J. Surgical treatment of full-thickness macular holes using autologous serum. Eye (Lond) 1996;10(Pt 5):593–599. doi: 10.1038/eye.1996.136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yannuzzi L. A., Rohrer K. T., Tindel L. J., Sobel R. S., Costanza M. A., Shields W., Zang E. Fluorescein angiography complication survey. Ophthalmology. 1986 May;93(5):611–617. doi: 10.1016/s0161-6420(86)33697-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Bustros S. Vitrectomy for prevention of macular holes. Results of a randomized multicenter clinical trial. Vitrectomy for Prevention of Macular Hole Study Group. Ophthalmology. 1994 Jun;101(6):1055–1060. doi: 10.1016/s0161-6420(94)31218-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- von Rückmann A., Fitzke F. W., Bird A. C. Fundus autofluorescence in age-related macular disease imaged with a laser scanning ophthalmoscope. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 1997 Feb;38(2):478–486. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]