Abstract

AIM—The management of suppurative keratitis due to filamentous fungi presents severe problems in tropical countries. The aim was to demonstrate the efficacy of chlorhexidine 0.2% drops as an inexpensive antimicrobial agent, which could be widely distributed for fungal keratitis. METHODS—Successive patients presenting to the Chittagong Eye Institute and Training Complex with corneal ulcers were admitted to the trial when fungal hyphae had been seen on microscopy. They were randomised to drop treatment with chlorhexidine gluconate 0.2% or the standard local treatment natamycin 2.5%. The diameters, depths, and other features of the ulcers were measured and photographed at regular intervals. The outcome measures were healing at 21 days and presence or absence of toxicity. If there was not a favourable response at 5 days, "treatment failure" was recorded and the treatment was changed to one or more of three options, which included econazole 1% in the latter part of the trial. RESULTS—71 patients were recruited to the trial, of which 35 were randomised to chlorhexidine and 36 to natamycin. One allocated to natamycin grew bacteria and therefore was excluded from the analysis. None of the severe ulcers was fully healed at 21 days of treatment, but three of those allocated to chlorhexidine eventually healed in times up to 60 days. Of the non-severe ulcers, 66.7% were healed at 21 days with chlorhexidine and 36.0% with natamycin, a relative efficacy (RE) of 1.85 (CL 1.01-3.39, p = 0.04). If those ulcers were excluded where fungi were seen in the scraping but did not grow on culture, the estimated efficacy ratio does not change but becomes less precise because of smaller numbers. Equal numbers of Aspergillus (22) and Fusarium (22) were grown. The Aspergillus were the most resistant to either primary treatment. CONCLUSIONS—Chlorhexidine may have potential as an inexpensive topical agent for fungal keratitis and warrants further assessment as a first line treatment in situations where microbiological facilities and a range of antifungal agents are not available. Keywords: fungal keratitis; corneal ulcers; chlorhexidine; Bangladesh

Full Text

The Full Text of this article is available as a PDF (165.8 KB).

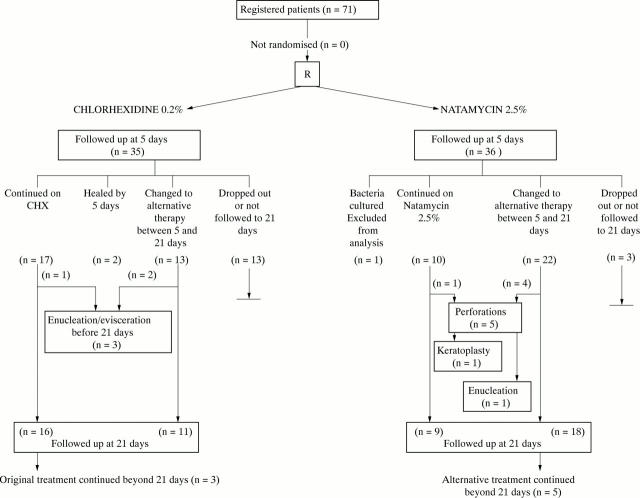

Figure 1 .

Flow of patients through the various stages of the trial.

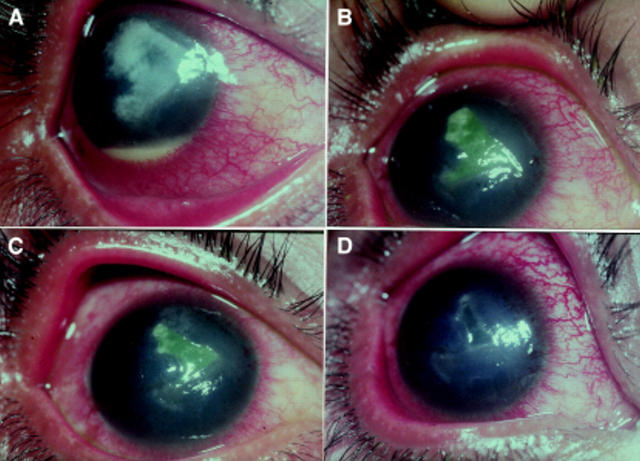

Figure 2 .

Serial photographs of healing of ulcer, classified as severe, by 0.2% chlorhexidine. Study no 25, 15 year old male student, secondary to injury with fingernail. Fungus identified was Fusarium sp. (A) At presentation, with hypopyon, (B) 5th day, (C) 7th day, (D) 10th day, residual epithelial defect. Fully healed on day 26.

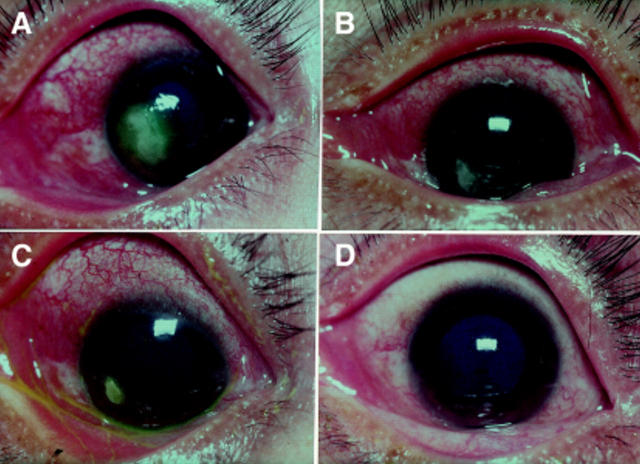

Figure 3 .

Serial photographs of healing of ulcer by 0.2% chlorhexidine. Study no 4, 45 year old female farmer, no history of injury. Fungus identified was Fusarium sp. (A) Ulcer at presentation, (B) fifth day, (C) 7th day. (D) Ulcer healed on 17th day.

Selected References

These references are in PubMed. This may not be the complete list of references from this article.

- Dunlop A. A., Wright E. D., Howlader S. A., Nazrul I., Husain R., McClellan K., Billson F. A. Suppurative corneal ulceration in Bangladesh. A study of 142 cases examining the microbiological diagnosis, clinical and epidemiological features of bacterial and fungal keratitis. Aust N Z J Ophthalmol. 1994 May;22(2):105–110. doi: 10.1111/j.1442-9071.1994.tb00775.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gasset A. R., Ishii Y. Cytotoxicity of chlorhexidine. Can J Ophthalmol. 1975 Jan;10(1):98–100. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hagan M., Wright E., Newman M., Dolin P., Johnson G. Causes of suppurative keratitis in Ghana. Br J Ophthalmol. 1995 Nov;79(11):1024–1028. doi: 10.1136/bjo.79.11.1024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamill M. B., Osato M. S., Wilhelmus K. R. Experimental evaluation of chlorhexidine gluconate for ocular antisepsis. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1984 Dec;26(6):793–796. doi: 10.1128/aac.26.6.793. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hay J., Kirkness C. M., Seal D. V., Wright P. Drug resistance and Acanthamoeba keratitis: the quest for alternative antiprotozoal chemotherapy. Eye (Lond) 1994;8(Pt 5):555–563. doi: 10.1038/eye.1994.137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liesegang T. J., Forster R. K. Spectrum of microbial keratitis in South Florida. Am J Ophthalmol. 1980 Jul;90(1):38–47. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9394(14)75075-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin M. J., Rahman M. R., Johnson G. J., Srinivasan M., Clayton Y. M. Mycotic keratitis: susceptibility to antiseptic agents. Int Ophthalmol. 1995;19(5):299–302. doi: 10.1007/BF00130925. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nisbet I. T., Graham D. M., Spicer P. E., Tibbs G. J. Chlorhexidine as an effective agent against Chlamydia trachomatis in vitro and in vivo. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1979 Dec;16(6):855–857. doi: 10.1128/aac.16.6.855. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rahman M. R., Minassian D. C., Srinivasan M., Martin M. J., Johnson G. J. Trial of chlorhexidine gluconate for fungal corneal ulcers. Ophthalmic Epidemiol. 1997 Sep;4(3):141–149. doi: 10.3109/09286589709115721. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seal D., Hay J., Kirkness C., Morrell A., Booth A., Tullo A., Ridgway A., Armstrong M. Successful medical therapy of Acanthamoeba keratitis with topical chlorhexidine and propamidine. Eye (Lond) 1996;10(Pt 4):413–421. doi: 10.1038/eye.1996.92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomas P. A. Mycotic keratitis--an underestimated mycosis. J Med Vet Mycol. 1994;32(4):235–256. doi: 10.1080/02681219480000321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams G., Billson F., Husain R., Howlader S. A., Islam N., McClellan K. Microbiological diagnosis of suppurative keratitis in Bangladesh. Br J Ophthalmol. 1987 Apr;71(4):315–321. doi: 10.1136/bjo.71.4.315. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams G., McClellan K., Billson F. Suppurative keratitis in rural Bangladesh: the value of gram stain in planning management. Int Ophthalmol. 1991 Mar;15(2):131–135. doi: 10.1007/BF00224467. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]