Abstract

BACKGROUND/AIMS—A photostress recovery test was designed to differentiate macular diseases from optic nerve disorders, but recently an abnormal recovery time was reported in glaucoma. The purpose of this study was to search for the difference in abnormality of the photostress recovery test between glaucoma and idiopathic central serous chorioretinopathy (ICSC). METHODS—This study involved 21 normal subjects, 14 patients, with ICSC and 10 patients with primary open angle glaucoma (POAG). A scanning laser ophthalmoscope (SLO) was used with microperimetry for bleaching the test point and measuring the recovery of sensitivity. Photostress recovery time (SLO-PSRT) could be measured at extrafoveal points outside and inside the affected area. The initial sensitivity change and the time constant of recovery after bleaching were calculated by fitting an exponential equation to the data. RESULTS—In normal subjects, neither the initial sensitivity change nor the time constant were correlated with the location of the test point. In 14 patients with ICSC, the initial sensitivity change in the detached area was significantly smaller than that in the unaffected area which was not significantly different from that in the age matched normal subjects. The time constant in the detached area was significantly longer than that in the unaffected area, which was not significantly different from that in the normal subjects. In 10 patients with POAG, the initial sensitivity change inside and outside the scotoma was not significantly different from that of age matched normal subjects. The time constant inside the scotoma was significantly longer than that outside the scotoma, which was not significantly different from that of the age matched normal subjects. CONCLUSION—Both ICSC and POAG showed a prolonged time constant of recovery, but the initial sensitivity change was reduced only in ICSC. The difference in our results between ICSC and POAG may be caused by the difference of the retinal pathology. Further, the SLO-PSRT is very useful when the lesion is located outside the fovea. Keywords: glaucoma; idiopathic central serous chorioretinopathy; photostress recovery test; scanning laser ophthalmoscope

Full Text

The Full Text of this article is available as a PDF (162.8 KB).

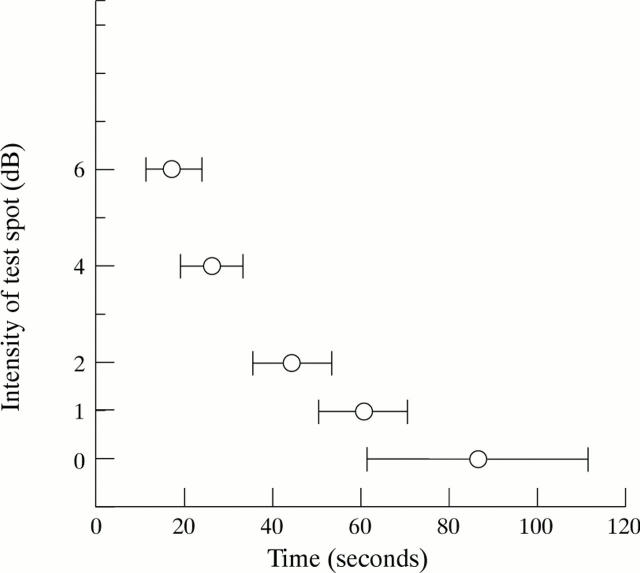

Figure 1 .

(A) The image on the fundus monitor of a SLO during extrafoveal bleaching. The area with stripes was covered with a Wratten filter. A cross indicates a fixating target and "A" indicates a testing point. (B) The image of the fundus monitor during foveal bleaching. Four crosses indicate fixating targets and "A" indicates a testing point.

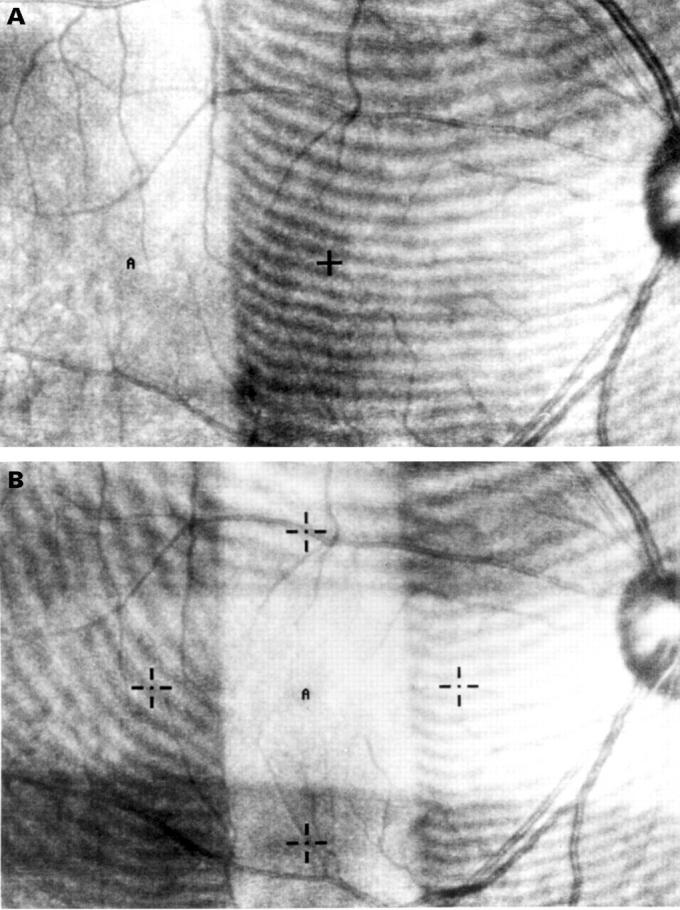

Figure 2 .

(A) Location of the testing points for 12 normal subjects. The recovery times were measured at the points, 7.5° temporally, nasally, above and below from the fovea, 15° temporally and at the fovea. (B) Location of the testing points in idiopathic central serous chorioretinopathy (ICSC) group. (C) Location of the testing points in primary open angle glaucoma (POAG) group.

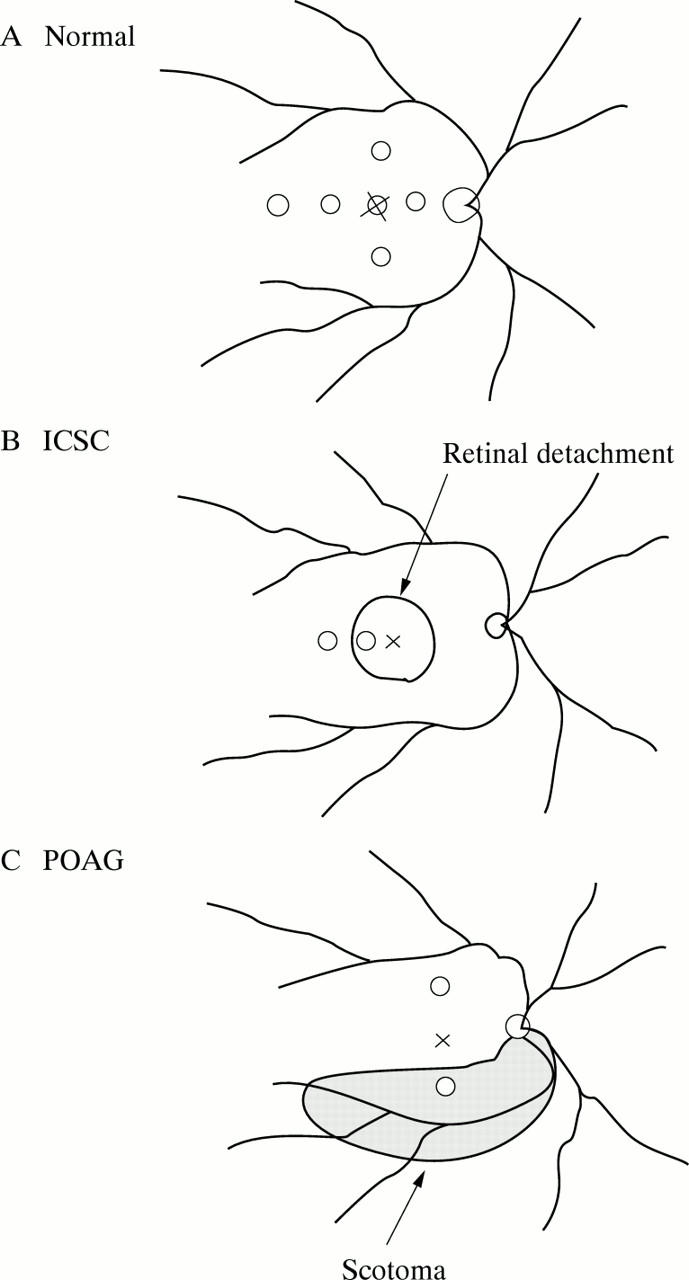

Figure 3 .

The recovery times to test spots of five intensities at 7.5° temporal point in normal subjects.

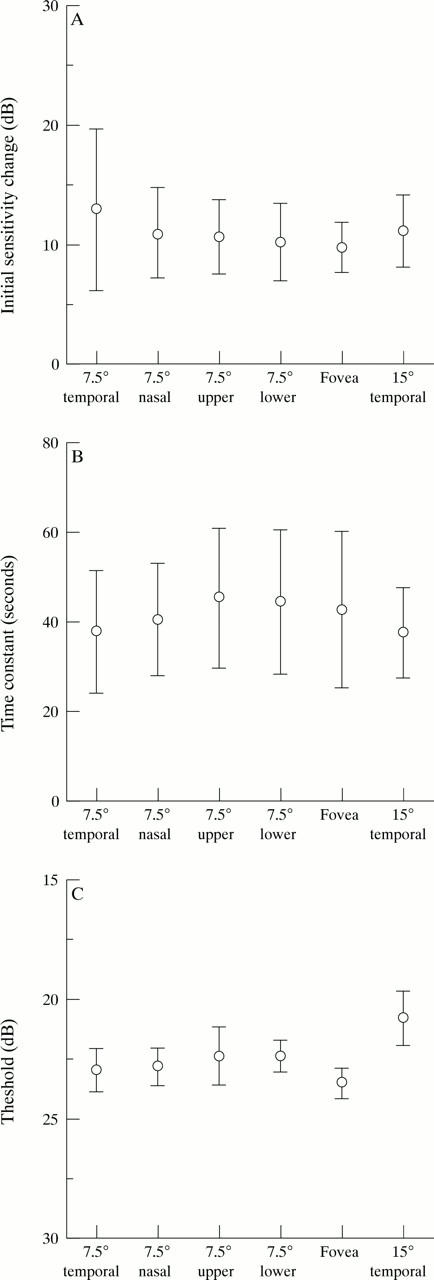

Figure 4 .

The initial sensitivity change(A), the time constant (B), and the threshold for the red target (C) at six points in 12 normal subjects.

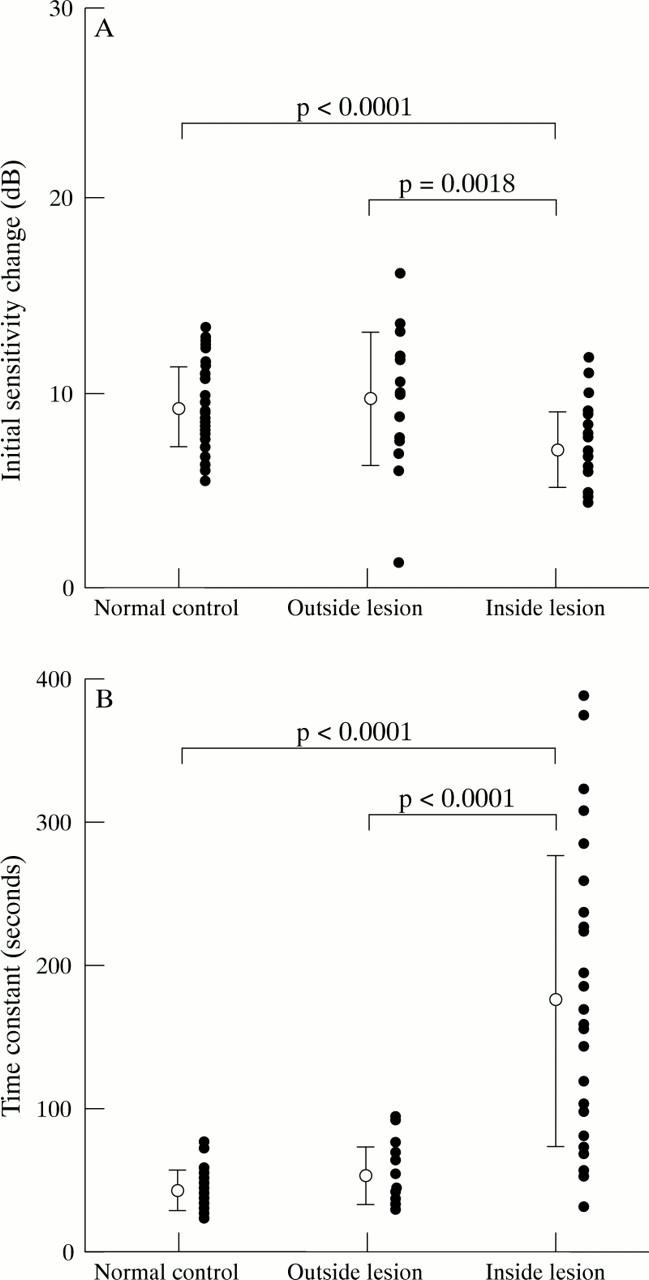

Figure 5 .

The initial sensitivity change (A) and the time constant (B) in normal control group, and outside and inside the lesion in ICSC group. The closed circles indicate individual datum points.

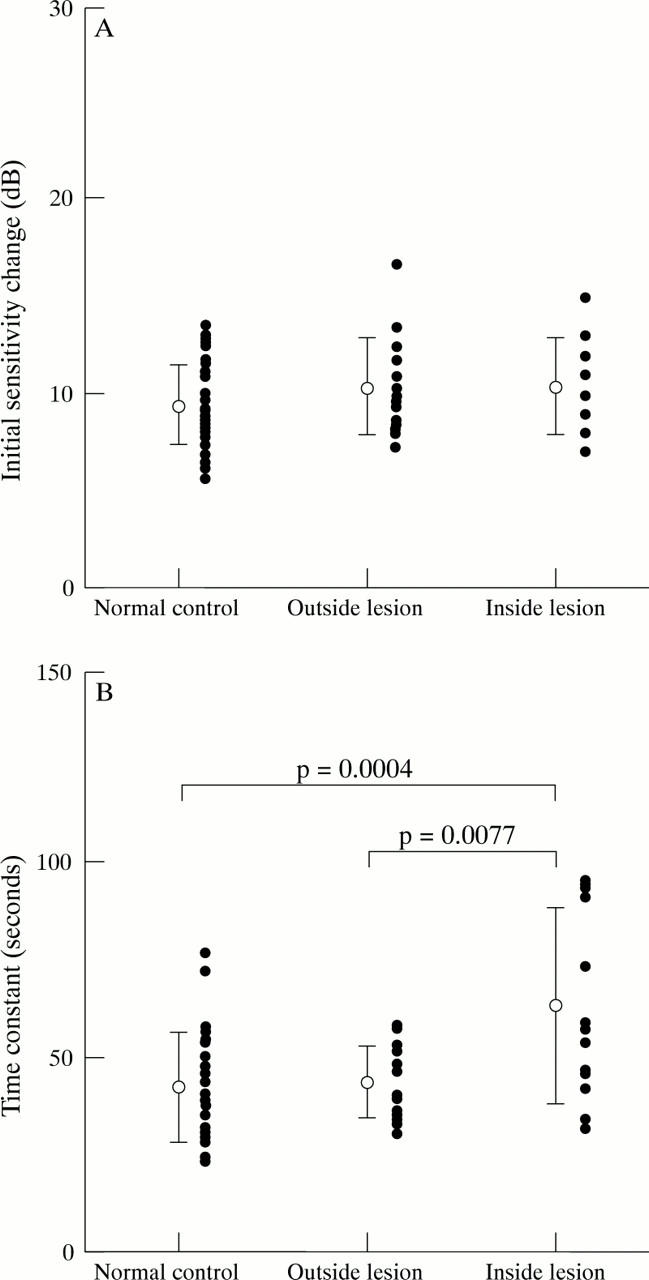

Figure 6 .

The initial sensitivity change (A) and the time constant (B) in normal control group, and outside and inside the lesion in POAG group. The closed circles indicate individual datum points.

Selected References

These references are in PubMed. This may not be the complete list of references from this article.

- Alvis D. L. Electroretinographic changes in controlled chronic open-angle glaucoma. Am J Ophthalmol. 1966 Jan;61(1):121–131. doi: 10.1016/0002-9394(66)90756-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BAKER H. D., RUSHTON W. A. THE RED-SENSITIVE PIGMENT IN NORMAL CONES. J Physiol. 1965 Jan;176:56–72. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1965.sp007535. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CHILARIS G. A. Recovery time after macular illumination as a diagnostic and prognostic test. Am J Ophthalmol. 1962 Feb;53:311–314. doi: 10.1016/0002-9394(62)91181-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DOWLING J. E. Chemistry of visual adaptation in the rat. Nature. 1960 Oct 8;188:114–118. doi: 10.1038/188114a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dineen J. T., Hendrickson A. E. Age correlated differences in the amount of retinal degeneration after striate cortex lesions in monkeys. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 1981 Nov;21(5):749–752. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duncker G., Krastel H. Ocular digitalis effects in normal subjects. Lens Eye Toxic Res. 1990;7(3-4):281–303. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eisner A. Multiple components in photopic dark adaptation. J Opt Soc Am A. 1986 May;3(5):655–666. doi: 10.1364/josaa.3.000655. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fazio D. T., Heckenlively J. R., Martin D. A., Christensen R. E. The electroretinogram in advanced open-angle glaucoma. Doc Ophthalmol. 1986 Jun 16;63(1):45–54. doi: 10.1007/BF00153011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Franchi A., Magni R., Lodigiani L., Cordella M. VEP pattern after photostress: an index of macular function. Graefes Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol. 1987;225(4):291–294. doi: 10.1007/BF02150151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glaser J. S., Savino P. J., Sumers K. D., McDonald S. A., Knighton R. W. The photostress recovery test in the clinical assessment of visual function. Am J Ophthalmol. 1977 Feb;83(2):255–260. doi: 10.1016/0002-9394(77)90624-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guyer D. R., Yannuzzi L. A., Slakter J. S., Sorenson J. A., Ho A., Orlock D. Digital indocyanine green videoangiography of central serous chorioretinopathy. Arch Ophthalmol. 1994 Aug;112(8):1057–1062. doi: 10.1001/archopht.1994.01090200063023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harnois C., Malenfant M., Dupont A., Labrie F. Ocular toxicity of Anandron in patients treated for prostatic cancer. Br J Ophthalmol. 1986 Jun;70(6):471–473. doi: 10.1136/bjo.70.6.471. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayashi K., Hasegawa Y., Tokoro T. Indocyanine green angiography of central serous chorioretinopathy. Int Ophthalmol. 1986 Apr;9(1):37–41. doi: 10.1007/BF00225936. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hollins M., Alpern M. Dark adaptation and visual pigment regeneration in human cones. J Gen Physiol. 1973 Oct;62(4):430–447. doi: 10.1085/jgp.62.4.430. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jonas J. B., Zäch F. M., Naumann G. O. Dark adaptation in glaucomatous and nonglaucomatous optic nerve atrophy. Graefes Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol. 1990;228(4):321–325. doi: 10.1007/BF00920055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kawasaki K., Mukoh S., Yonemura D., Fujii S., Segawa Y. Acetazolamide-induced changes of the membrane potentials of the retinal pigment epithelial cell. Doc Ophthalmol. 1986 Nov 15;63(4):375–381. doi: 10.1007/BF00220229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lakowski R., Drance S. M., Goldthwaite D. Chromatic extrafoveal dark adaptation function in normal and glaucomatous eyes. Mod Probl Ophthalmol. 1976;17:304–310. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lovasik J. V. An electrophysiological investigation of the macular photostress test. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 1983 Apr;24(4):437–441. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MAGDER H. Test for central serous retinopathy based on clinical observations and trial. Am J Ophthalmol. 1960 Jan;49:147–150. doi: 10.1016/0002-9394(60)92674-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ogata H. [Electrophysiological study on glaucoma. Part I. Electroretinogram in primary glaucoma (author's transl)]. Nippon Ganka Gakkai Zasshi. 1976 Nov 10;80(11):1555–1564. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Panda S., Jonas J. B. Decreased photoreceptor count in human eyes with secondary angle-closure glaucoma. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 1992 Jul;33(8):2532–2536. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parisi V., Bucci M. G. Visual evoked potentials after photostress in patients with primary open-angle glaucoma and ocular hypertension. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 1992 Feb;33(2):436–442. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quigley H. A., Addicks E. M., Green W. R., Maumenee A. E. Optic nerve damage in human glaucoma. II. The site of injury and susceptibility to damage. Arch Ophthalmol. 1981 Apr;99(4):635–649. doi: 10.1001/archopht.1981.03930010635009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quigley H. A., Addicks E. M., Green W. R. Optic nerve damage in human glaucoma. III. Quantitative correlation of nerve fiber loss and visual field defect in glaucoma, ischemic neuropathy, papilledema, and toxic neuropathy. Arch Ophthalmol. 1982 Jan;100(1):135–146. doi: 10.1001/archopht.1982.01030030137016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quigley H. A., Miller N. R., George T. Clinical evaluation of nerve fiber layer atrophy as an indicator of glaucomatous optic nerve damage. Arch Ophthalmol. 1980 Sep;98(9):1564–1571. doi: 10.1001/archopht.1980.01020040416003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quigley H. A., Sanchez R. M., Dunkelberger G. R., L'Hernault N. L., Baginski T. A. Chronic glaucoma selectively damages large optic nerve fibers. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 1987 Jun;28(6):913–920. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- RUSHTON W. A. Rhodopsin measurement and dark-adaptation in a subject deficient in cone vision. J Physiol. 1961 Apr;156:193–205. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1961.sp006668. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saito A., Miyake Y., Wang J. X., Yagasaki K., Matsumoto Y., Horio N., Horiguchi M. [Foveal cone densitometer and changes in foveal cone pigments with aging]. Nippon Ganka Gakkai Zasshi. 1995 Feb;99(2):212–219. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Severin S. L., Tour R. L., Kershaw R. H. Macular function and the photostress test 1. Arch Ophthalmol. 1967 Jan;77(1):2–7. doi: 10.1001/archopht.1967.00980020004002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Severin S. L., Tour R. L., Kershaw R. H. Macular function and the photostress test 2. Arch Ophthalmol. 1967 Feb;77(2):163–167. doi: 10.1001/archopht.1967.00980020165004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sherman M. D., Henkind P. Photostress recovery in chronic open angle glaucoma. Br J Ophthalmol. 1988 Sep;72(9):641–645. doi: 10.1136/bjo.72.9.641. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wolfensberger T. J., Mahieu I., Jarvis-Evans J., Boulton M., Carter N. D., Nógrádi A., Hollande E., Bird A. C. Membrane-bound carbonic anhydrase in human retinal pigment epithelium. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 1994 Aug;35(9):3401–3407. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu G., Weiter J. J., Santos S., Ginsburg L., Villalobos R. The macular photostress test in diabetic retinopathy and age-related macular degeneration. Arch Ophthalmol. 1990 Nov;108(11):1556–1558. doi: 10.1001/archopht.1990.01070130058030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zabriskie N. A., Kardon R. H. The pupil photostress test. Ophthalmology. 1994 Jun;101(6):1122–1130. doi: 10.1016/s0161-6420(94)31211-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zuege P., Drance S. M. Studies of dark adaptation of discrete paracentral retinal areas in glaucomatous subjects. Am J Ophthalmol. 1967 Jul;64(1):56–63. doi: 10.1016/0002-9394(67)93343-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Meel G. J., Smith V. C., Pokorny J., van Norren D. Foveal densitometry in central serous choroidopathy. Am J Ophthalmol. 1984 Sep 15;98(3):359–368. doi: 10.1016/0002-9394(84)90329-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]