Abstract

BACKGROUND/AIMS—A simulation model of the human eye was developed. It was applied to the determination of the physical and mechanical conditions of impacting foreign bodies causing intraocular foreign body (IOFB) injuries. METHODS—Modules of the Hypermesh (Altair Engineering, Tokyo, Japan) were used for solid modelling, geometric construction, and finite element mesh creation based on information obtained from cadaver eyes. The simulations were solved by a supercomputer using the finite element analysis (FEA) program PAM-CRASH (Nihon ESI, Tokyo, Japan). It was assumed that rupture occurs at a strain of 18.0% in the cornea and 6.8% in the sclera and at a stress of 9.4 MPa for both cornea and sclera. Blunt-shaped missiles were shot and set to impact on the surface of the cornea or sclera at velocities of 30 and 60 m/s, respectively. RESULTS—According to the simulation, the sizes of missile above which corneal rupture occurred at velocities of 30 and 60 m/s were 1.95 and 0.82 mm. The missile sizes causing scleral rupture were 0.95 and 0.75 mm at velocities of 30 and 60 m/s. CONCLUSIONS—These results suggest that this FEA model has potential usefulness as a simulation tool for ocular injury and it may provide useful information for developing protective measures against industrial and traffic ocular injuries.

Full Text

The Full Text of this article is available as a PDF (157.8 KB).

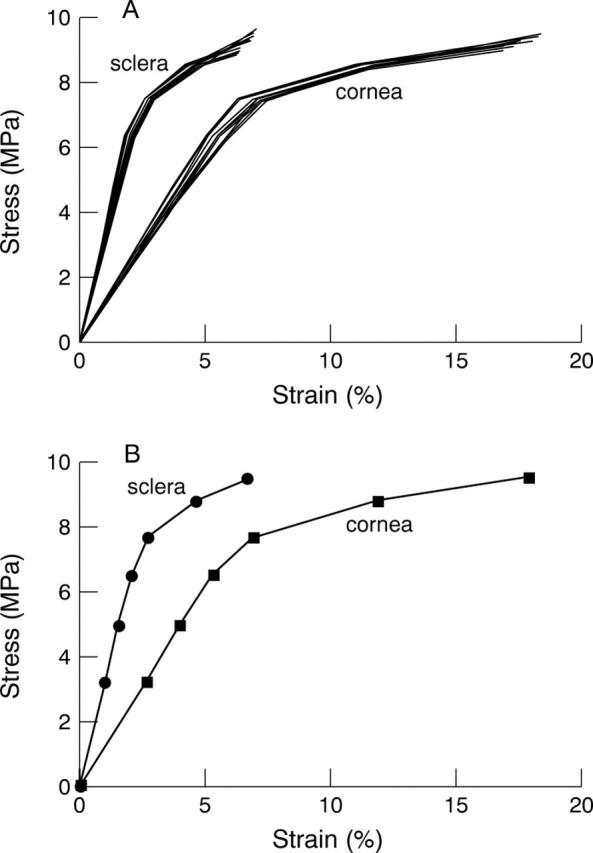

Figure 1 .

Stress-strain curves for cornea and sclera. Each line represents the value from 12 corneal or scleral samples (A). Stress-strain curve for the simulation model is derived from experimental values and the data of past reports. Penetrating ocular injury is assumed to occur at a strain of 18.0% in cornea and 6.8% in sclera (B).

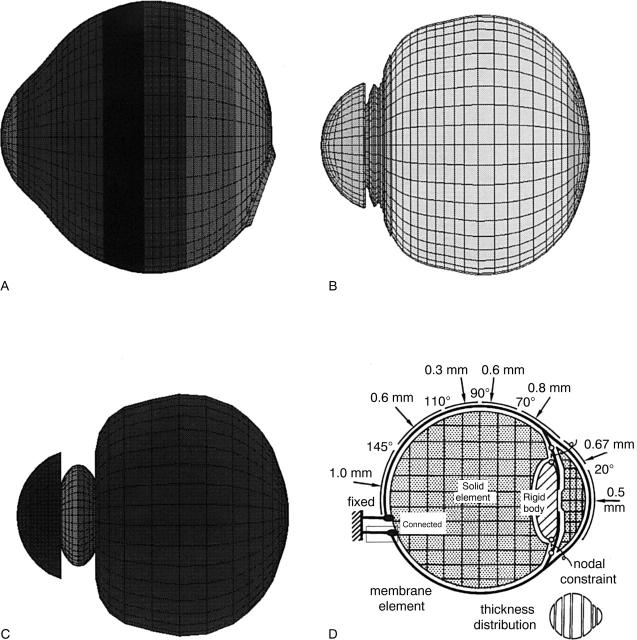

Figure 2 .

Meshing principles of the eye. The model of the human eye is composed of three layers, outer (A; cornea and sclera (superficial layer)), middle (B; cornea and sclera (deep layer), iris, ciliary body, choroid, and retina), and inner (C; aqueous humour, lens, and vitreous). Mesh principle in the cross sectional view is indicated (D).

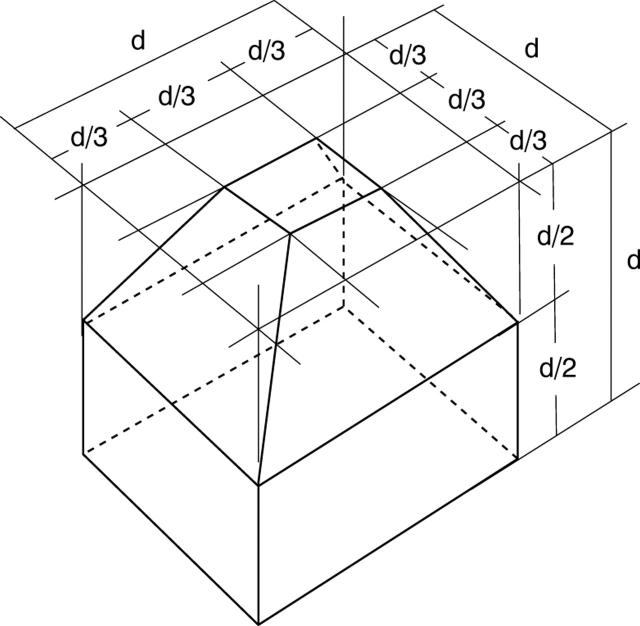

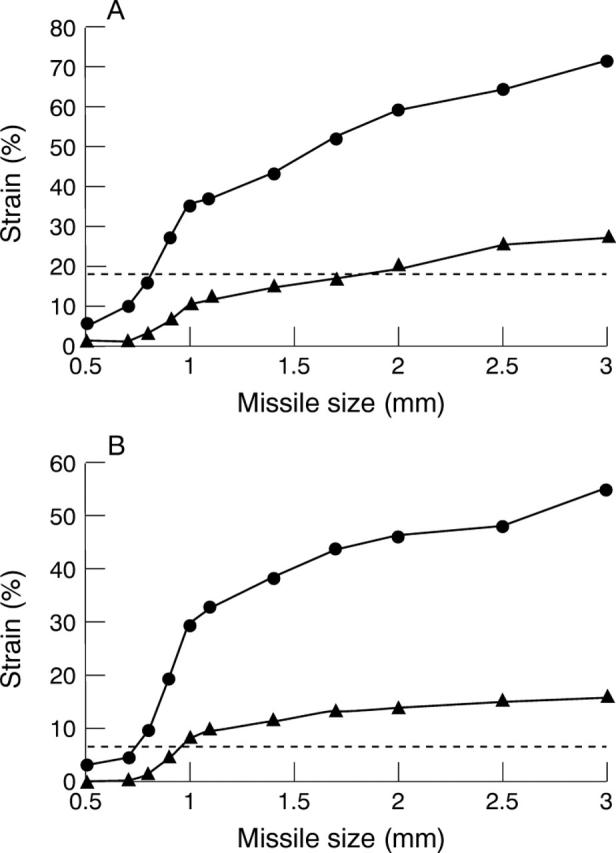

Figure 3 .

Missile shape. The missile shape used in the simulation is blunt. Size of the missile is indicated as d.

Figure 4 .

Axial strain and axial size curve of cornea (A) and sclera (B). The threshold of rupture is 18.0% for cornea and 6.8% for sclera as indicated by the broken line. The two conditions of different velocities of missiles, 30 m/s (H) and 60 m/s (J), are demonstrated.

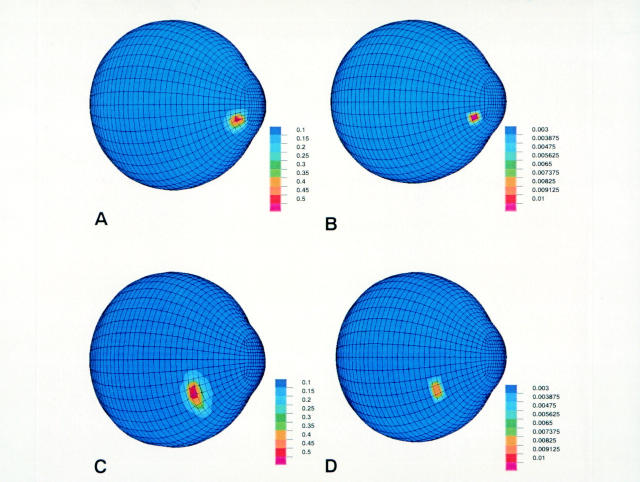

Figure 5 .

Example of missile impacts on cornea and sclera. Simulation in four situations, 3.0, 60, cornea (size (mm), velocity (m/s), impacted tissue) (A), 0.5, 60, cornea (B), 3.0, 60, sclera (C) and 0.5, 60, sclera (D), is displayed. Colour bar indicates axial strain. Rupture is represented in A and C.

Selected References

These references are in PubMed. This may not be the complete list of references from this article.

- Battaglioli J. L., Kamm R. D. Measurements of the compressive properties of scleral tissue. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 1984 Jan;25(1):59–65. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buzard K. A. Introduction to biomechanics of the cornea. Refract Corneal Surg. 1992 Mar-Apr;8(2):127–138. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Canavan Y. M., O'Flaherty M. J., Archer D. B., Elwood J. H. A 10-year survey of eye injuries in Northern Ireland, 1967-76. Br J Ophthalmol. 1980 Aug;64(8):618–625. doi: 10.1136/bjo.64.8.618. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carnell P. H., Vito R. P. A model for estimating corneal stiffness using an indenter. J Biomech Eng. 1992 Nov;114(4):549–552. doi: 10.1115/1.2894111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greene P. R. Closed-form ametropic pressure-volume and ocular rigidity solutions. Am J Optom Physiol Opt. 1985 Dec;62(12):870–878. doi: 10.1097/00006324-198512000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hanna K. D., Jouve F. E., Waring G. O., 3rd, Ciarlet P. G. Computer simulation of arcuate and radial incisions involving the corneoscleral limbus. Eye (Lond) 1989;3(Pt 2):227–239. doi: 10.1038/eye.1989.32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hassett P. D., Kelleher C. C. The epidemiology of occupational penetrating eye injuries in Ireland. Occup Med (Lond) 1994 Sep;44(4):209–211. doi: 10.1093/occmed/44.4.209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoeltzel D. A., Altman P., Buzard K., Choe K. Strip extensiometry for comparison of the mechanical response of bovine, rabbit, and human corneas. J Biomech Eng. 1992 May;114(2):202–215. doi: 10.1115/1.2891373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnston S. S. The changing pattern of injury. Trans Ophthalmol Soc U K. 1975 Jul;95(2):307–310. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koval R., Teller J., Belkin M., Romem M., Yanko L., Savir H. The Israeli Ocular Injuries Study. A nationwide collaborative study. Arch Ophthalmol. 1988 Jun;106(6):776–780. doi: 10.1001/archopht.1988.01060130846037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ku D. N., Greene P. R. Scleral creep in vitro resulting from cyclic pressure pulses: applications to myopia. Am J Optom Physiol Opt. 1981 Jul;58(7):528–535. doi: 10.1097/00006324-198107000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuhn F., Morris R., Witherspoon C. D., Heimann K., Jeffers J. B., Treister G. A standardized classification of ocular trauma. Ophthalmology. 1996 Feb;103(2):240–243. doi: 10.1016/s0161-6420(96)30710-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liggett P. E., Pince K. J., Barlow W., Ragen M., Ryan S. J. Ocular trauma in an urban population. Review of 1132 cases. Ophthalmology. 1990 May;97(5):581–584. doi: 10.1016/s0161-6420(90)32539-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Macewen C. J. Eye injuries: a prospective survey of 5671 cases. Br J Ophthalmol. 1989 Nov;73(11):888–894. doi: 10.1136/bjo.73.11.888. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nash I. S., Greene P. R., Foster C. S. Comparison of mechanical properties of keratoconus and normal corneas. Exp Eye Res. 1982 Nov;35(5):413–424. doi: 10.1016/0014-4835(82)90040-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reichel E., Miller D., Blanco E., Mastanduno R. The elastic modulus of central and perilimbal bovine cornea. Ann Ophthalmol. 1989 Jun;21(6):205–208. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saari K. M., Parvi V. Occupational eye injuries in Finland. Acta Ophthalmol Suppl. 1984;161:17–28. doi: 10.1111/j.1755-3768.1984.tb06779.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schrader W. Perforating injuries: causes and risks are changing. A retrospective study. Ger J Ophthalmol. 1993 Apr;2(2):76–82. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taber L. A. Large deformation mechanics of the enucleated eyeball. J Biomech Eng. 1984 Aug;106(3):229–234. doi: 10.1115/1.3138487. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Viano D. C., King A. I., Melvin J. W., Weber K. Injury biomechanics research: an essential element in the prevention of trauma. J Biomech. 1989;22(5):403–417. doi: 10.1016/0021-9290(89)90201-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vito R. P., Shin T. J., McCarey B. E. A mechanical model of the cornea: the effects of physiological and surgical factors on radial keratotomy surgery. Refract Corneal Surg. 1989 Mar-Apr;5(2):82–88. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wykes W. N. A 10-year survey of penetrating eye injuries in Gwent, 1976-85. Br J Ophthalmol. 1988 Aug;72(8):607–611. doi: 10.1136/bjo.72.8.607. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]