Full Text

The Full Text of this article is available as a PDF (215.6 KB).

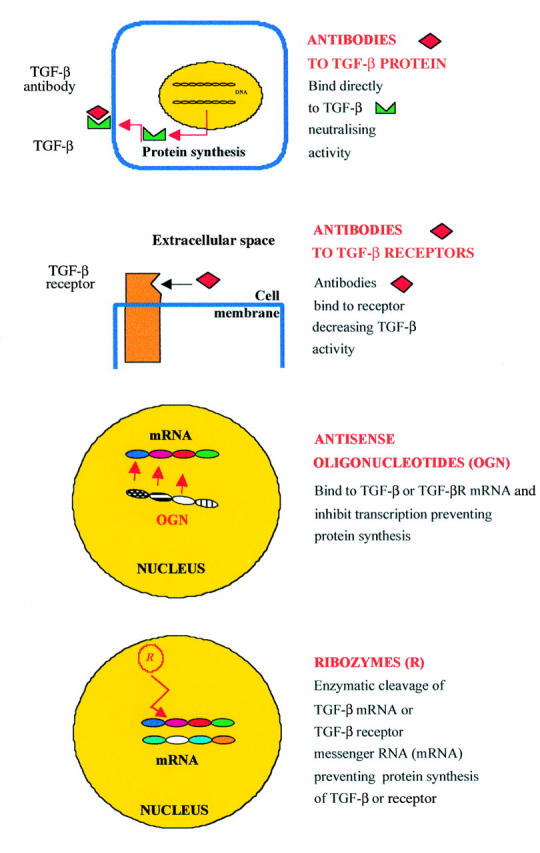

Figure 1 .

Targets for molecular therapy. TGF-β activity can be inhibited in several ways using different molecular approaches. Therapy may be directed against TGF-β and receptor proteins using fully human neutralising monoclonal antibodies. Alternatively, inhibition of TGF-β and receptors at the level of gene expression is possible using antisense oligonucleotides or ribozymes, which act at the level of messenger RNA (mRNA) and prevent protein synthesis.

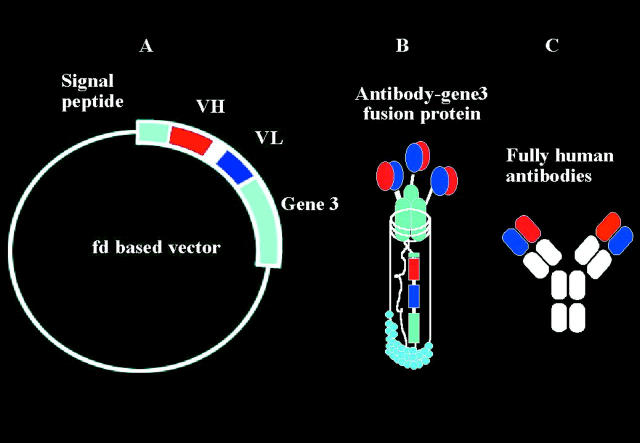

Figure 2 .

Phage antibodies. Fully human neutralising monoclonal antibodies can be made using the technique of phage display (Cambridge Antibody Technology, Melbourne UK). Human antibody light and heavy chains are identified from a large human antibody library. The human genes coding for these chains are then incorporated into a bacterial virus (phage) (A). When the phage infects a bacterium (usually, E coli), the bacterium makes the antibody protein which it displays on its surface (B). Specific clones binding to an antigen can then be amplified, and the whole antibody produced using recombinant methods (C).

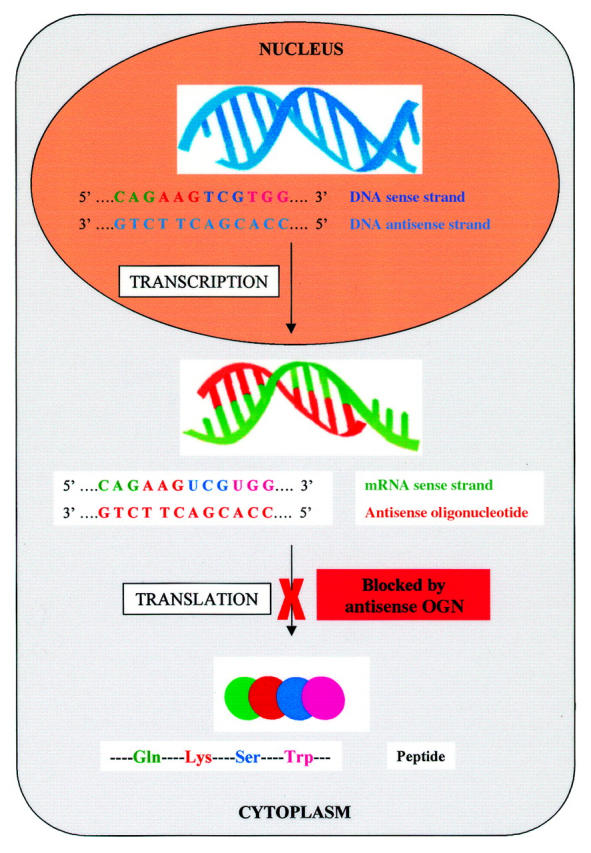

Figure 3 .

Antisense oligonucleotides. Antisense molecules are synthetic oligonucleotides that have been designed to be complementary to mRNA strands that code for the production of specific proteins. The target mRNA is transcribed from DNA in the nucleus and, on entering the cytoplasm, is bound by the antisense molecule. The binding of the mRNA sense strand stops translation of the mRNA, and hence synthesis of the protein.

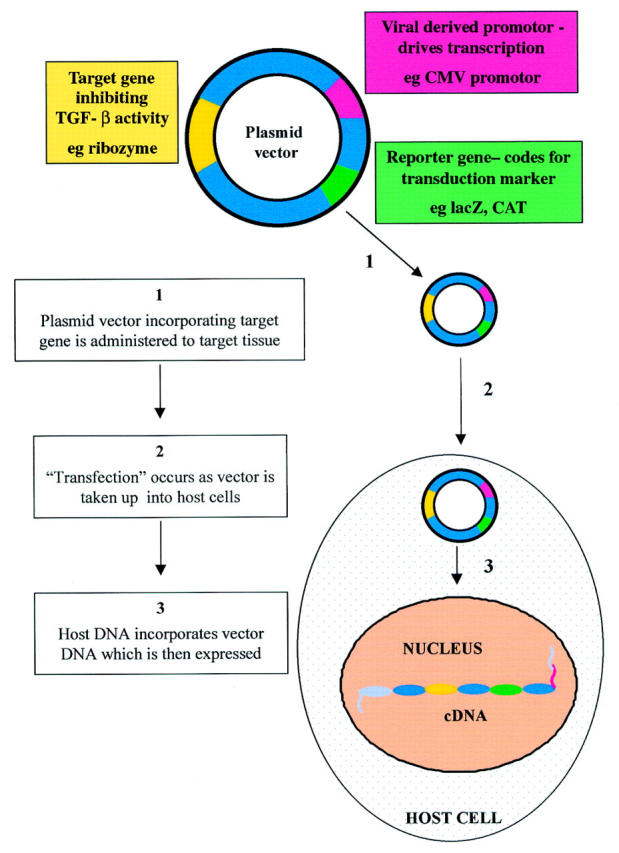

Figure 4 .

Gene transfer. Gene therapy depends on the successful transfer and delivery of the agents to specific tissues. A DNA vector—for example, a plasmid vector, which includes gene sequences for the target, a viral derived promoter, and a reporter can transfect cells in the target tissue.

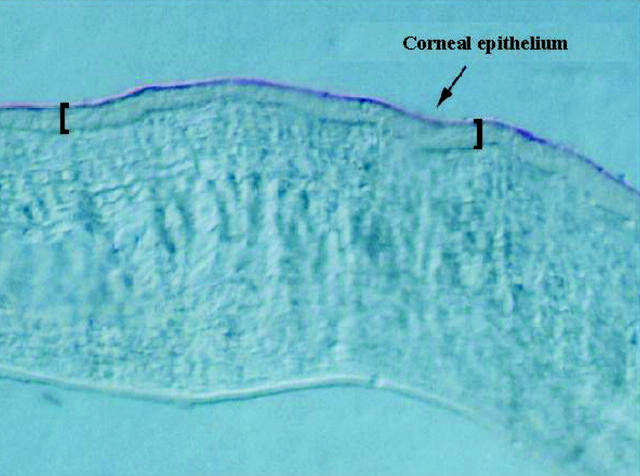

Figure 5 .

Gene transfer in cornea. Using our rabbit model,34 we show transduction of the corneal epithelium with a DNA plasmid expressing a CAT reporter gene has occurred, as detected with Texas red immunostaining (5 µm section, ×20 magnification)

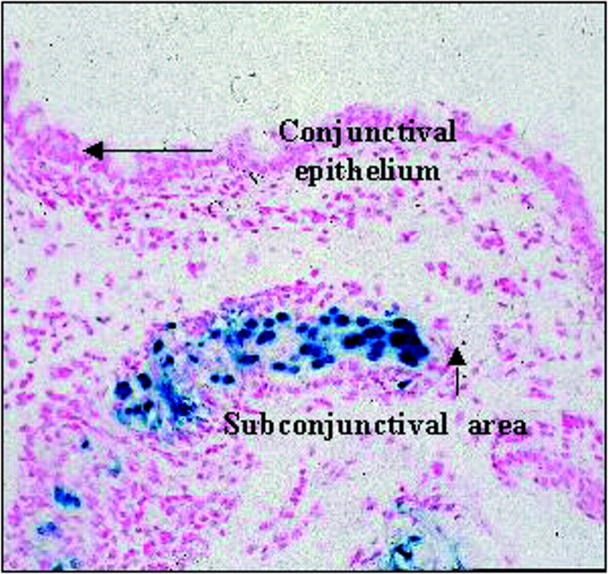

Figure 6 .

Gene transfer in conjunctiva. Using our mouse model of conjunctival scarring,33 we have shown that there is transduction of fibroblasts and mononuclear cells in the subconjunctival space with an AV vector expressing a lacZ reporter gene (AV.CMV.LacZnuc). Positive expression is indicated by galactosidase activity seen as blue (nuclear fast red counterstain, 5 µm section, ×80 magnification).

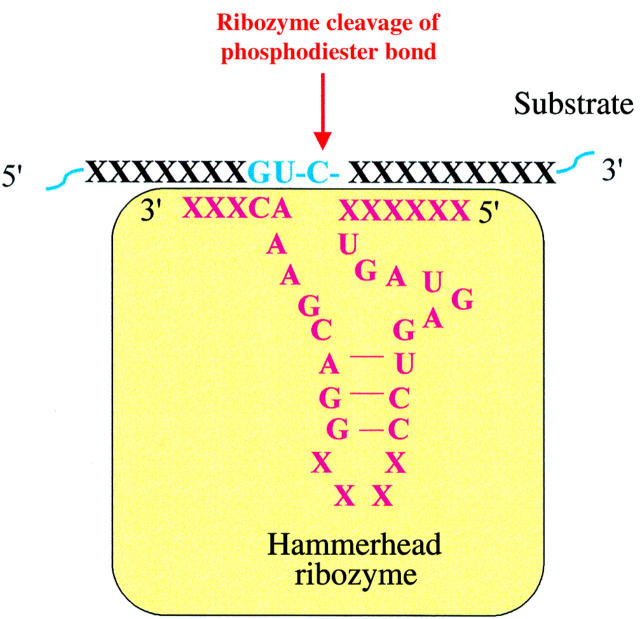

Figure 7 .

Ribozymes. Ribozymes are RNA molecules that are able enzymatically to cleave specific RNA bonds. Like antisense oligonucleotides, they can be designed to target any mRNA of specific proteins. The cleavage of mRNA by the ribozyme leads to inhibition of translation and protein production.

Selected References

These references are in PubMed. This may not be the complete list of references from this article.

- Abraham N. G., Da Silva J. L., Dunn M. W., Kigasawa K., Shibahara S. Retinal pigment epithelial cell-based gene therapy against hemoglobin toxicity. Int J Mol Med. 1998 Apr;1(4):657–663. doi: 10.3892/ijmm.1.4.657. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Addicks E. M., Quigley H. A., Green W. R., Robin A. L. Histologic characteristics of filtering blebs in glaucomatous eyes. Arch Ophthalmol. 1983 May;101(5):795–798. doi: 10.1001/archopht.1983.01040010795021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Akimoto M., Hangai M., Okazaki K., Kogishi J., Honda Y., Kaneda Y. Growth inhibition of cultured human Tenon's fibroblastic cells by targeting the E2F transcription factor. Exp Eye Res. 1998 Oct;67(4):395–401. doi: 10.1006/exer.1998.0531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ali R. R., Reichel M. B., Hunt D. M., Bhattacharya S. S. Gene therapy for inherited retinal degeneration. Br J Ophthalmol. 1997 Sep;81(9):795–801. doi: 10.1136/bjo.81.9.795. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Altman S. RNA enzyme-directed gene therapy. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1993 Dec 1;90(23):10898–10900. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.23.10898. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anderson W. F. Human gene therapy. Nature. 1998 Apr 30;392(6679 Suppl):25–30. doi: 10.1038/32058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bartel D. P., Szostak J. W. Isolation of new ribozymes from a large pool of random sequences [see comment]. Science. 1993 Sep 10;261(5127):1411–1418. doi: 10.1126/science.7690155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beardsley T. Making antisense. Drugs that turn off genes are entering human tests. Sci Am. 1992 Feb;266(2):107–108. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benn S. I., Whitsitt J. S., Broadley K. N., Nanney L. B., Perkins D., He L., Patel M., Morgan J. R., Swain W. F., Davidson J. M. Particle-mediated gene transfer with transforming growth factor-beta1 cDNAs enhances wound repair in rat skin. J Clin Invest. 1996 Dec 15;98(12):2894–2902. doi: 10.1172/JCI119118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clackson T., Hoogenboom H. R., Griffiths A. D., Winter G. Making antibody fragments using phage display libraries. Nature. 1991 Aug 15;352(6336):624–628. doi: 10.1038/352624a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Connor T. B., Jr, Roberts A. B., Sporn M. B., Danielpour D., Dart L. L., Michels R. G., de Bustros S., Enger C., Kato H., Lansing M. Correlation of fibrosis and transforming growth factor-beta type 2 levels in the eye. J Clin Invest. 1989 May;83(5):1661–1666. doi: 10.1172/JCI114065. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cordeiro M. F., Constable P. H., Alexander R. A., Bhattacharya S. S., Khaw P. T. Effect of varying the mitomycin-C treatment area in glaucoma filtration surgery in the rabbit. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 1997 Jul;38(8):1639–1646. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cordeiro M. F., Reichel M. B., Gay J. A., D'Esposita F., Alexander R. A., Khaw P. T. Transforming growth factor-beta1, -beta2, and -beta3 in vivo: effects on normal and mitomycin C-modulated conjunctival scarring. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 1999 Aug;40(9):1975–1982. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Critchlow M. A., Bland Y. S., Ashhurst D. E. The effect of exogenous transforming growth factor-beta 2 on healing fractures in the rabbit. Bone. 1995 May;16(5):521–527. doi: 10.1016/8756-3282(95)00085-r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dean N. M., Griffey R. H. Identification and characterization of second-generation antisense oligonucleotides. Antisense Nucleic Acid Drug Dev. 1997 Jun;7(3):229–233. doi: 10.1089/oli.1.1997.7.229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dorai T., Kobayashi H., Holland J. F., Ohnuma T. Modulation of platelet-derived growth factor-beta mRNA expression and cell growth in a human mesothelioma cell line by a hammerhead ribozyme. Mol Pharmacol. 1994 Sep;46(3):437–444. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drenser K. A., Timmers A. M., Hauswirth W. W., Lewin A. S. Ribozyme-targeted destruction of RNA associated with autosomal-dominant retinitis pigmentosa. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 1998 Apr;39(5):681–689. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elder M. J., Dart J. K., Lightman S. Conjunctival fibrosis in ocular cicatricial pemphigoid--the role of cytokines. Exp Eye Res. 1997 Aug;65(2):165–176. doi: 10.1006/exer.1997.0311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fakler B., Herlitze S., Amthor B., Zenner H. P., Ruppersberg J. P. Short antisense oligonucleotide-mediated inhibition is strongly dependent on oligo length and concentration but almost independent of location of the target sequence. J Biol Chem. 1994 Jun 10;269(23):16187–16194. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hart S. L., Arancibia-Cárcamo C. V., Wolfert M. A., Mailhos C., O'Reilly N. J., Ali R. R., Coutelle C., George A. J., Harbottle R. P., Knight A. M. Lipid-mediated enhancement of transfection by a nonviral integrin-targeting vector. Hum Gene Ther. 1998 Mar 1;9(4):575–585. doi: 10.1089/hum.1998.9.4-575. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jakobovits A. Production of fully human antibodies by transgenic mice. Curr Opin Biotechnol. 1995 Oct;6(5):561–566. doi: 10.1016/0958-1669(95)80093-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jampel H. D., Roche N., Stark W. J., Roberts A. B. Transforming growth factor-beta in human aqueous humor. Curr Eye Res. 1990 Oct;9(10):963–969. doi: 10.3109/02713689009069932. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jester J. V., Barry-Lane P. A., Petroll W. M., Olsen D. R., Cavanagh H. D. Inhibition of corneal fibrosis by topical application of blocking antibodies to TGF beta in the rabbit. Cornea. 1997 Mar;16(2):177–187. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kernacki K. A., Goebel D. J., Poosch M. S., Hazlett L. D. Early TIMP gene expression after corneal infection with Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 1998 Feb;39(2):331–335. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Köhler G., Howe S. C., Milstein C. Fusion between immunoglobulin-secreting and nonsecreting myeloma cell lines. Eur J Immunol. 1976 Apr;6(4):292–295. doi: 10.1002/eji.1830060411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewin A. S., Drenser K. A., Hauswirth W. W., Nishikawa S., Yasumura D., Flannery J. G., LaVail M. M. Ribozyme rescue of photoreceptor cells in a transgenic rat model of autosomal dominant retinitis pigmentosa. Nat Med. 1998 Aug;4(8):967–971. doi: 10.1038/nm0898-967. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marcusson E. G., Bhat B., Manoharan M., Bennett C. F., Dean N. M. Phosphorothioate oligodeoxyribonucleotides dissociate from cationic lipids before entering the nucleus. Nucleic Acids Res. 1998 Apr 15;26(8):2016–2023. doi: 10.1093/nar/26.8.2016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Massagué J. The transforming growth factor-beta family. Annu Rev Cell Biol. 1990;6:597–641. doi: 10.1146/annurev.cb.06.110190.003121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McLean J. W., Fox E. A., Baluk P., Bolton P. B., Haskell A., Pearlman R., Thurston G., Umemoto E. Y., McDonald D. M. Organ-specific endothelial cell uptake of cationic liposome-DNA complexes in mice. Am J Physiol. 1997 Jul;273(1 Pt 2):H387–H404. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1997.273.1.H387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moore M. J. Ribozymes. Exploration by lamp light. Nature. 1995 Apr 27;374(6525):766–767. doi: 10.1038/374766a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Myers J. S., Gomes J. A., Siepser S. B., Rapuano C. J., Eagle R. C., Jr, Thom S. B. Effect of transforming growth factor beta 1 on stromal haze following excimer laser photorefractive keratectomy in rabbits. J Refract Surg. 1997 Jul-Aug;13(4):356–361. doi: 10.3928/1081-597X-19970701-11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nikol S. Possible uses of gene therapy in reducing coronary restenosis. Heart. 1997 Nov;78(5):426–428. doi: 10.1136/hrt.78.5.426. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rachal W. F., Burton T. C. Changing concepts of failures after retinal detachment surgery. Arch Ophthalmol. 1979 Mar;97(3):480–483. doi: 10.1001/archopht.1979.01020010230008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reichel M. B., Ali R. R., Thrasher A. J., Hunt D. M., Bhattacharya S. S., Baker D. Immune responses limit adenovirally mediated gene expression in the adult mouse eye. Gene Ther. 1998 Aug;5(8):1038–1046. doi: 10.1038/sj.gt.3300691. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reichel M. B., Cordeiro M. F., Alexander R. A., Cree I. A., Bhattacharya S. S., Khaw P. T. New model of conjunctival scarring in the mouse eye. Br J Ophthalmol. 1998 Sep;82(9):1072–1077. doi: 10.1136/bjo.82.9.1072. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roberts A. B., Sporn M. B., Assoian R. K., Smith J. M., Roche N. S., Wakefield L. M., Heine U. I., Liotta L. A., Falanga V., Kehrl J. H. Transforming growth factor type beta: rapid induction of fibrosis and angiogenesis in vivo and stimulation of collagen formation in vitro. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1986 Jun;83(12):4167–4171. doi: 10.1073/pnas.83.12.4167. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saed G. M., Ladin D., Olson J., Han X., Hou Z., Fivenson D. Analysis of p53 gene mutations in keloids using polymerase chain reaction-based single-strand conformational polymorphism and DNA sequencing. Arch Dermatol. 1998 Aug;134(8):963–967. doi: 10.1001/archderm.134.8.963. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sugawa N., Ueda S., Nakagawa Y., Nishino H., Nosaka K., Iwashima A., Kurimoto M. An antisense EGFR oligodeoxynucleotide enveloped in Lipofectin induces growth inhibition in human malignant gliomas in vitro. J Neurooncol. 1998 Sep;39(3):237–244. doi: 10.1023/a:1005903002865. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilson C., Szostak J. W. In vitro evolution of a self-alkylating ribozyme. Nature. 1995 Apr 27;374(6525):777–782. doi: 10.1038/374777a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Winter G., Milstein C. Man-made antibodies. Nature. 1991 Jan 24;349(6307):293–299. doi: 10.1038/349293a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu-Pong S., Weiss T. L., Hunt C. A. Antisense c-myc oligonucleotide cellular uptake and activity. Antisense Res Dev. 1994 Fall;4(3):155–163. doi: 10.1089/ard.1994.4.155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]