Abstract

AIMS—To evaluate temporal contrast sensitivity with full field, peripheral, and central stimulation and to determine the most sensitive corresponding retinal area for glaucoma damage. METHODS—Temporal contrast sensitivity was determined either with a full field, a peripheral annular area from 30° to 90°, or a central area from 0° to 30° at a frequency of 37.1 Hz. 232 eyes of 232 subjects were included. They were classified into four groups: eyes with ocular hypertension (OHT, n = 54), "preperimetric" glaucomas (n = 73) with glaucomatous optic disc abnormalities but no visual field loss, "perimetric" glaucomas (n = 53) with visual field loss, and 52 normals. RESULTS—In all four groups, temporal contrast senstitivity was almost equal with full field and peripheral, but significantly higher than with central stimulation (p <0.001). With regard to the diagnostic power of the three different stimulus areas, OHTs and glaucomas were found to be best discriminated from normals by peripheral stimulation. CONCLUSIONS—According to these results, temporal contrast sensitivity seems to be determined by peripheral retinal areas. As the diagnostic power of the three different stimulus areas was best with the peripheral stimulation, this condition should be used for early glaucoma diagnosis. Keywords: temporal contrast sensitivity; full field flicker; glaucoma; ocular hypertension

Full Text

The Full Text of this article is available as a PDF (121.5 KB).

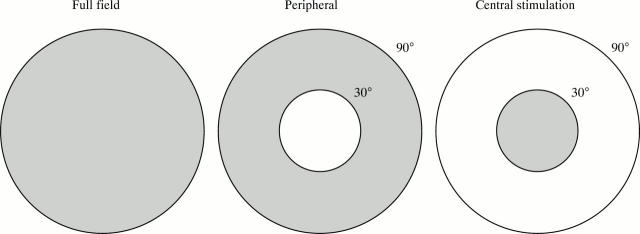

Figure 1 .

A full field bowl (58 cm in diameter) was used to produce a homogeneous white flickering light. The areas to be tested were either the full field, a peripheral annular area from 30° to 90°, or a central area from 0° to 30°. Those areas not used for stimulation were screened by black cardboard.

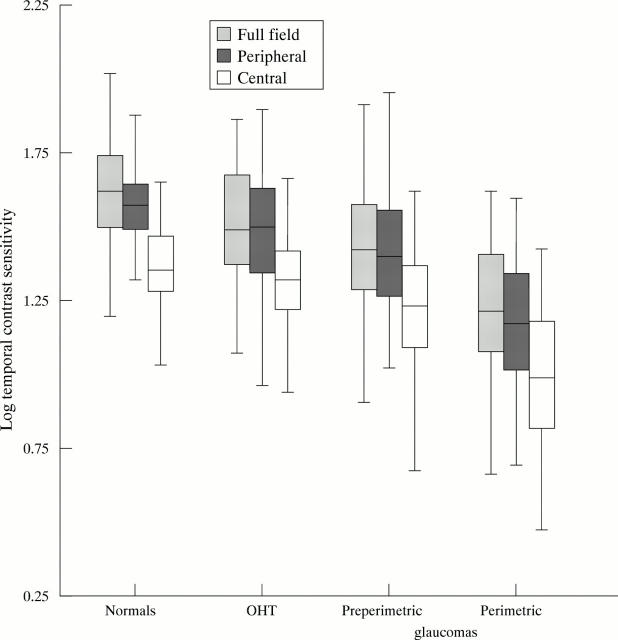

Figure 2 .

Box plots of temporal contrast sensitivity values determined with three different stimuli (full field, peripheral, and central flicker test) in four different subjects groups (OHT = ocular hypertensives). The temporal contrast sensitivity was almost equal with full field and peripheral, but significantly higher (p <0.001) than with central stimulation. The boxes include 50% of measured values (25% and 75% percentiles) and show the position of the median (horizontal line). Error bars indicate the 1.5-fold of the interquartile distance from the upper and lower box edges. The position of the medians (solid lines within the boxes) illustrates the markedly lower temporal contrast sensitivity with central compared with full field and peripheral stimulation. Additionally, it shows the decreasing temporal contrast sensitivity with increasing stage of glaucoma with all three stimulus areas.

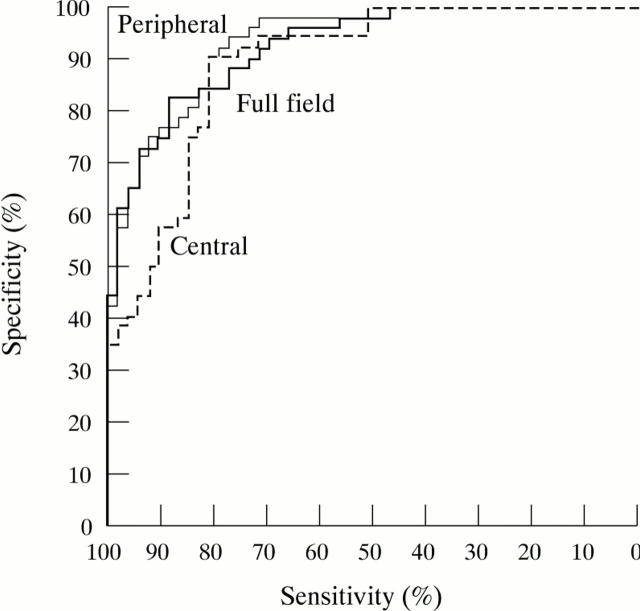

Figure 3 .

Receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curves for determination of temporal contrast sensitivity in "perimetric" glaucomas with three different stimulus areas (full field, peripheral, and central stimulation). Although there is only little difference between the three stimulus areas, for specificities >90% peripheral stimulation offers highest sensitivities. The next sensitive test condition is the full field stimulus, followed by the central stimulus which is least sensitive.

Selected References

These references are in PubMed. This may not be the complete list of references from this article.

- Airaksinen P. J., Tuulonen A., Alanko H. I. Rate and pattern of neuroretinal rim area decrease in ocular hypertension and glaucoma. Arch Ophthalmol. 1992 Feb;110(2):206–210. doi: 10.1001/archopht.1992.01080140062028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anderson R. S., O'Brien C. Psychophysical evidence for a selective loss of M ganglion cells in glaucoma. Vision Res. 1997 Apr;37(8):1079–1083. doi: 10.1016/s0042-6989(96)00260-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arden G. B., Jacobson J. J. A simple grating test for contrast sensitivity: preliminary results indicate value in screening for glaucoma. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 1978 Jan;17(1):23–32. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Atkin A., Bodis-Wollner I., Podos S. M., Wolkstein M., Mylin L., Nitzberg S. Flicker threshold and pattern VEP latency in ocular hypertension and glaucoma. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 1983 Nov;24(11):1524–1528. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Atkin A., Bodis-Wollner I., Wolkstein M., Moss A., Podos S. M. Abnormalities of central contrast sensitivity in glaucoma. Am J Ophthalmol. 1979 Aug;88(2):205–211. doi: 10.1016/0002-9394(79)90467-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aulhorn E., Köst G. Rauschfeldkampimetrie. Eine neuartige perimetrische Untersuchungsweise. Klin Monbl Augenheilkd. 1988 Apr;192(4):284–288. doi: 10.1055/s-2008-1050114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Austin M. W., O'Brien C. J., Wishart P. K. Flicker perimetry using a luminance threshold strategy at frequencies from 5-25 Hz in glaucoma, ocular hypertension and normal controls. Curr Eye Res. 1994 Oct;13(10):717–723. doi: 10.3109/02713689409047005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baez K. A., McNaught A. I., Dowler J. G., Poinoosawmy D., Fitzke F. W., Hitchings R. A. Motion detection threshold and field progression in normal tension glaucoma. Br J Ophthalmol. 1995 Feb;79(2):125–128. doi: 10.1136/bjo.79.2.125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borgmann C., Steiner H., Dutton G. N. Optimum technique of light brightness assessment in control subjects and patients with ocular hypertension and glaucoma. Ophthalmologica. 1991;203(3):126–132. doi: 10.1159/000310238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bosworth C. F., Sample P. A., Weinreb R. N. Perimetric motion thresholds are elevated in glaucoma suspects and glaucoma patients. Vision Res. 1997 Jul;37(14):1989–1997. doi: 10.1016/s0042-6989(96)00326-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Breton M. E., Wilson T. W., Wilson R., Spaeth G. L., Krupin T. Temporal contrast sensitivity loss in primary open-angle glaucoma and glaucoma suspects. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 1991 Oct;32(11):2931–2941. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bullimore M. A., Wood J. M., Swenson K. Motion perception in glaucoma. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 1993 Dec;34(13):3526–3533. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caprioli J. Discrimination between normal and glaucomatous eyes. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 1992 Jan;33(1):153–159. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cummins D., MacMillan E. S., Heron G., Dutton G. N. Simultaneous interocular brightness sense testing in ocular hypertension and glaucoma. Arch Ophthalmol. 1994 Sep;112(9):1198–1203. doi: 10.1001/archopht.1994.01090210082020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Falcão-Reis F., O'Donoghue E., Buceti R., Hitchings R. A., Arden G. B. Peripheral contrast sensitivity in glaucoma and ocular hypertension. Br J Ophthalmol. 1990 Dec;74(12):712–716. doi: 10.1136/bjo.74.12.712. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feghali J. G., Bocquet X., Charlier J., Odom J. V. Static flicker perimetry in glaucoma and ocular hypertension. Curr Eye Res. 1991 Mar;10(3):205–212. doi: 10.3109/02713689109003442. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flammer J., Drance S. M., Augustiny L., Funkhouser A. Quantification of glaucomatous visual field defects with automated perimetry. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 1985 Feb;26(2):176–181. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frisén L. High-pass resolution perimetry. A clinical review. Doc Ophthalmol. 1993;83(1):1–25. doi: 10.1007/BF01203566. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glovinsky Y., Quigley H. A., Drum B., Bissett R. A., Jampel H. D. A whole-field scotopic retinal sensitivity test for the detection of early glaucoma damage. Arch Ophthalmol. 1992 Apr;110(4):486–490. doi: 10.1001/archopht.1992.01080160064031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hart W. M., Jr, Burde R. M. Color contrast perimetry. The spatial distribution of color defects in optic nerve and retinal diseases. Ophthalmology. 1985 Jun;92(6):768–776. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hart W. M., Jr, Gordon M. O. Color perimetry of glaucomatous visual field defects. Ophthalmology. 1984 Apr;91(4):338–346. doi: 10.1016/s0161-6420(84)34281-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holopigian K., Seiple W., Mayron C., Koty R., Lorenzo M. Electrophysiological and psychophysical flicker sensitivity in patients with primary open-angle glaucoma and ocular hypertension. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 1990 Sep;31(9):1863–1868. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horn F. K., Jonas J. B., Korth M., Jünemann A., Gründler A. The full-field flicker test in early diagnosis of chronic open-angle glaucoma. Am J Ophthalmol. 1997 Mar;123(3):313–319. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9394(14)70126-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horn F., Martus P., Korth M. Comparison of temporal and spatiotemporal contrast-sensitivity tests in normal subjects and glaucoma patients. Ger J Ophthalmol. 1995 Mar;4(2):97–102. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joffe K. M., Raymond J. E., Chrichton A. Motion coherence perimetry in glaucoma and suspected glaucoma. Vision Res. 1997 Apr;37(7):955–964. doi: 10.1016/s0042-6989(96)00221-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson C. A., Adams A. J., Casson E. J., Brandt J. D. Blue-on-yellow perimetry can predict the development of glaucomatous visual field loss. Arch Ophthalmol. 1993 May;111(5):645–650. doi: 10.1001/archopht.1993.01090050079034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson C. A., Samuels S. J. Screening for glaucomatous visual field loss with frequency-doubling perimetry. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 1997 Feb;38(2):413–425. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jonas J. B., Königsreuther K. A. Optic disk appearance in ocular hypertensive eyes. Am J Ophthalmol. 1994 Jun 15;117(6):732–740. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9394(14)70316-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Korth M., Horn F., Martus P. Einfacher zeitlicher Kontrastempfindlichkeits-Test in der Glaukom-Diagnostik. Klin Monbl Augenheilkd. 1993 Aug;203(2):99–103. doi: 10.1055/s-2008-1045654. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Korth M., Horn F., Storck B., Jonas J. B. Spatial and spatiotemporal contrast sensitivity of normal and glaucoma eyes. Graefes Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol. 1989;227(5):428–435. doi: 10.1007/BF02172893. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lachenmayr B., Gleissner M., Rothbächer H. Automatisierte Flimmerperimetrie. Fortschr Ophthalmol. 1989;86(6):695–701. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lundh B. L. Central and peripheral contrast sensitivity for static and dynamic sinusoidal gratings in glaucoma. Acta Ophthalmol (Copenh) 1985 Oct;63(5):487–492. doi: 10.1111/j.1755-3768.1985.tb05233.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lundh B. L., Gottvall E. Peripheral contrast sensitivity for dynamic sinusoidal gratings in early glaucoma. Acta Ophthalmol Scand. 1995 Jun;73(3):202–206. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0420.1995.tb00269.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quigley H. A., Dunkelberger G. R., Green W. R. Chronic human glaucoma causing selectively greater loss of large optic nerve fibers. Ophthalmology. 1988 Mar;95(3):357–363. doi: 10.1016/s0161-6420(88)33176-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quigley H. A., Katz J., Derick R. J., Gilbert D., Sommer A. An evaluation of optic disc and nerve fiber layer examinations in monitoring progression of early glaucoma damage. Ophthalmology. 1992 Jan;99(1):19–28. doi: 10.1016/s0161-6420(92)32018-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quigley H. A., Sanchez R. M., Dunkelberger G. R., L'Hernault N. L., Baginski T. A. Chronic glaucoma selectively damages large optic nerve fibers. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 1987 Jun;28(6):913–920. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raninen A., Rovamo J. Retinal ganglion-cell density and receptive-field size as determinants of photopic flicker sensitivity across the human visual field. J Opt Soc Am A. 1987 Aug;4(8):1620–1626. doi: 10.1364/josaa.4.001620. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ruben S., Fitzke F. Correlation of peripheral displacement thresholds and optic disc parameters in ocular hypertension. Br J Ophthalmol. 1994 Apr;78(4):291–294. doi: 10.1136/bjo.78.4.291. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sample P. A., Taylor J. D., Martinez G. A., Lusky M., Weinreb R. N. Short-wavelength color visual fields in glaucoma suspects at risk. Am J Ophthalmol. 1993 Feb 15;115(2):225–233. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9394(14)73928-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silverman S. E., Trick G. L., Hart W. M., Jr Motion perception is abnormal in primary open-angle glaucoma and ocular hypertension. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 1990 Apr;31(4):722–729. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stamper R. L. The effect of glaucoma on central visual function. Trans Am Ophthalmol Soc. 1984;82:792–826. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Teoh S. L., Allan D., Dutton G. N., Foulds W. S. Brightness discrimination and contrast sensitivity in chronic glaucoma--a clinical study. Br J Ophthalmol. 1990 Apr;74(4):215–219. doi: 10.1136/bjo.74.4.215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trick G. L., Steinman S. B., Amyot M. Motion perception deficits in glaucomatous optic neuropathy. Vision Res. 1995 Aug;35(15):2225–2233. doi: 10.1016/0042-6989(94)00311-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tuulonen A., Airaksinen P. J. Initial glaucomatous optic disk and retinal nerve fiber layer abnormalities and their progression. Am J Ophthalmol. 1991 Apr 15;111(4):485–490. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9394(14)72385-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tyler C. W. Analysis of visual modulation sensitivity. II. Peripheral retina and the role of photoreceptor dimensions. J Opt Soc Am A. 1985 Mar;2(3):393–398. doi: 10.1364/josaa.2.000393. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tyler C. W. Analysis of visual modulation sensitivity. III. Meridional variations in peripheral flicker sensitivity. J Opt Soc Am A. 1987 Aug;4(8):1612–1619. doi: 10.1364/josaa.4.001612. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tyler C. W. Specific deficits of flicker sensitivity in glaucoma and ocular hypertension. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 1981 Feb;20(2):204–212. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tytla M. E., Trope G. E., Buncic J. R. Flicker sensitivity in treated ocular hypertension. Ophthalmology. 1990 Jan;97(1):36–43. doi: 10.1016/s0161-6420(90)32630-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wall M., Jennisch C. S., Munden P. M. Motion perimetry identifies nerve fiber bundlelike defects in ocular hypertension. Arch Ophthalmol. 1997 Jan;115(1):26–33. doi: 10.1001/archopht.1997.01100150028003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zulauf M., LeBlanc R. P., Flammer J. Normal visual fields measured with Octopus-Program G1. II. Global visual field indices. Graefes Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol. 1994 Sep;232(9):516–522. doi: 10.1007/BF00181993. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zulauf M. Normal visual fields measured with Octopus Program G1. I. Differential light sensitivity at individual test locations. Graefes Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol. 1994 Sep;232(9):509–515. doi: 10.1007/BF00181992. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]