Abstract

AIMS—To determine the different morphologies of autosomal dominant cataract (ADC), assess the intra- and interfamilial variation in cataract morphology, and undertake a genetic linkage study to identify loci for genes causing ADC and detect the underlying mutation. METHODS—Patients were recruited from the ocular genetic database at Moorfields Eye Hospital. All individuals underwent an eye examination with particular attention to the lens including anterior segment photography where possible. Blood samples were taken for DNA extraction and genetic linkage analysis was carried out using polymorphic microsatellite markers. RESULTS—292 individuals from 16 large pedigrees with ADC were examined, of whom 161 were found to be affected. The cataract phenotypes could all be described as one of the eight following morphologies—anterior polar, posterior polar, nuclear, lamellar, coralliform, blue dot (cerulean), cortical, and pulverulent. The phenotypes varied in severity but the morphology was consistent within each pedigree, except in those affected by the pulverulent cataract, which showed considerable intrafamilial variation. Positive linkage was obtained in five families; in two families linkage was demonstrated to new loci and in three families linkage was demonstrated to previously described loci. In one of the families the underlying mutation was isolated. Exclusion data were obtained on five families. CONCLUSIONS—Although there is considerable clinical heterogeneity in ADC, the phenotype is usually consistent within families. There is extensive genetic heterogeneity and specific cataract phenotypes appear to be associated with mutations at more than one chromosome locus. In cases where the genetic mutation has been identified the molecular biology and clinical phenotype are closely associated.

Full Text

The Full Text of this article is available as a PDF (171.8 KB).

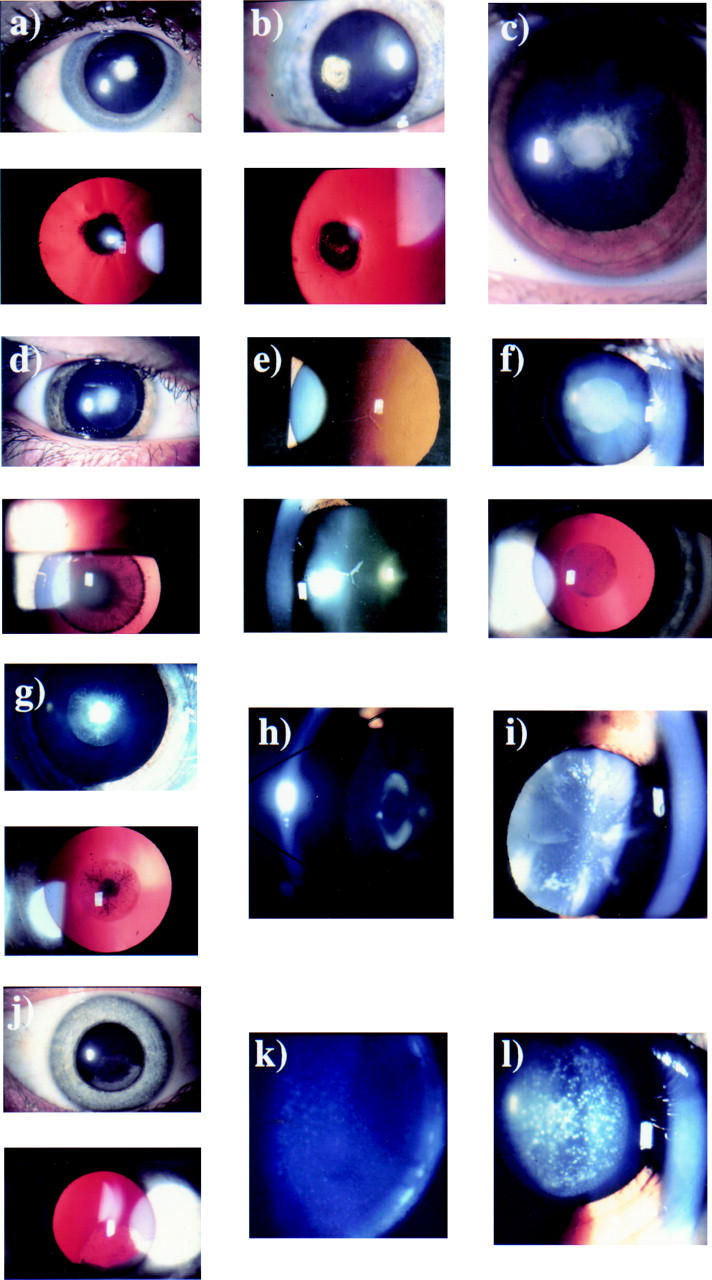

Figure 1 .

Autosomal dominant congenital cataract phenotypes. (a) Slit lamp and retroillumination view of anterior polar cataract (47 year old woman). (b) Slit lamp and retroillumination view of a stationary posterior polar cataract (49 year old woman). (c) Slit lamp view of a progressive posterior polar cataract (9 year old female). (d) Slit lamp and retroillumination view of a dense nuclear cataract (14 year old male). (e) Slit lamp and retroillumination view of nuclear opacities (50 year old woman). (f) Slit lamp and retroillumination view of the Coppock-like cataract with fine nuclear opacities (24 year old woman). (g) Slit lamp and retroillumination view of the Coppock-like cataract with dense central opacities (6 year old female). (h) Slit lamp view of lamellar cataract. (i) Slit lamp view of a blue dot (cerulean) cataract (32 year old man). (j) Slit lamp and retroillumination view of a cortical cataract (45 year old woman). (k) Slit lamp view of a fine pulverulent cataract (32 year old man). (l) Slit lamp view of large pulverulent opacities (12 year old female).

Selected References

These references are in PubMed. This may not be the complete list of references from this article.

- Armitage M. M., Kivlin J. D., Ferrell R. E. A progressive early onset cataract gene maps to human chromosome 17q24. Nat Genet. 1995 Jan;9(1):37–40. doi: 10.1038/ng0195-37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berry V., Ionides A. C., Moore A. T., Plant C., Bhattacharya S. S., Shiels A. A locus for autosomal dominant anterior polar cataract on chromosome 17p. Hum Mol Genet. 1996 Mar;5(3):415–419. doi: 10.1093/hmg/5.3.415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bodker F. S., Lavery M. A., Mitchell T. N., Lovrien E. W., Maumenee I. H. Microphthalmos in the presumed homozygous offspring of a first cousin marriage and linkage analysis of a locus in a family with autosomal dominant cerulean congenital cataracts. Am J Med Genet. 1990 Sep;37(1):54–59. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.1320370113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bouzas A. G. Anterior polar congenital cataract and corneal astigmatism. J Pediatr Ophthalmol Strabismus. 1992 Jul-Aug;29(4):210–212. doi: 10.3928/0191-3913-19920701-05. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brakenhoff R. H., Henskens H. A., van Rossum M. W., Lubsen N. H., Schoenmakers J. G. Activation of the gamma E-crystallin pseudogene in the human hereditary Coppock-like cataract. Hum Mol Genet. 1994 Feb;3(2):279–283. doi: 10.1093/hmg/3.2.279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cartier M., Breitman M. L., Tsui L. C. A frameshift mutation in the gamma E-crystallin gene of the Elo mouse. Nat Genet. 1992 Sep;2(1):42–45. doi: 10.1038/ng0992-42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chambers C., Russell P. Deletion mutation in an eye lens beta-crystallin. An animal model for inherited cataracts. J Biol Chem. 1991 Apr 15;266(11):6742–6746. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eiberg H., Lund A. M., Warburg M., Rosenberg T. Assignment of congenital cataract Volkmann type (CCV) to chromosome 1p36. Hum Genet. 1995 Jul;96(1):33–38. doi: 10.1007/BF00214183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eiberg H., Marner E., Rosenberg T., Mohr J. Marner's cataract (CAM) assigned to chromosome 16: linkage to haptoglobin. Clin Genet. 1988 Oct;34(4):272–275. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-0004.1988.tb02875.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gyapay G., Morissette J., Vignal A., Dib C., Fizames C., Millasseau P., Marc S., Bernardi G., Lathrop M., Weissenbach J. The 1993-94 Généthon human genetic linkage map. Nat Genet. 1994 Jun;7(2 Spec No):246–339. doi: 10.1038/ng0694supp-246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ionides A. C., Berry V., Mackay D. S., Moore A. T., Bhattacharya S. S., Shiels A. A locus for autosomal dominant posterior polar cataract on chromosome 1p. Hum Mol Genet. 1997 Jan;6(1):47–51. doi: 10.1093/hmg/6.1.47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ionides A., Berry V., Mackay D., Shiels A., Bhattacharya S., Moore A. Anterior polar cataract: clinical spectrum and genetic linkage in a single family. Eye (Lond) 1998;12(Pt 2):224–226. doi: 10.1038/eye.1998.53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jaafar M. S., Robb R. M. Congenital anterior polar cataract: a review of 63 cases. Ophthalmology. 1984 Mar;91(3):249–254. doi: 10.1016/s0161-6420(84)34297-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kador P. F., Fukui H. N., Fukushi S., Jernigan H. M., Jr, Kinoshita J. H. Philly mouse: a new model of hereditary cataract. Exp Eye Res. 1980 Jan;30(1):59–68. doi: 10.1016/0014-4835(80)90124-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kramer P., Yount J., Mitchell T., LaMorticella D., Carrero-Valenzuela R., Lovrien E., Maumenee I., Litt M. A second gene for cerulean cataracts maps to the beta crystallin region on chromosome 22. Genomics. 1996 Aug 1;35(3):539–542. doi: 10.1006/geno.1996.0395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lambert S. R., Drack A. V. Infantile cataracts. Surv Ophthalmol. 1996 May-Jun;40(6):427–458. doi: 10.1016/s0039-6257(96)82011-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Litt M., Carrero-Valenzuela R., LaMorticella D. M., Schultz D. W., Mitchell T. N., Kramer P., Maumenee I. H. Autosomal dominant cerulean cataract is associated with a chain termination mutation in the human beta-crystallin gene CRYBB2. Hum Mol Genet. 1997 May;6(5):665–668. doi: 10.1093/hmg/6.5.665. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Litt M., Kramer P., LaMorticella D. M., Murphey W., Lovrien E. W., Weleber R. G. Autosomal dominant congenital cataract associated with a missense mutation in the human alpha crystallin gene CRYAA. Hum Mol Genet. 1998 Mar;7(3):471–474. doi: 10.1093/hmg/7.3.471. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lubsen N. H., Renwick J. H., Tsui L. C., Breitman M. L., Schoenmakers J. G. A locus for a human hereditary cataract is closely linked to the gamma-crystallin gene family. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1987 Jan;84(2):489–492. doi: 10.1073/pnas.84.2.489. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mackay D., Ionides A., Berry V., Moore A., Bhattacharya S., Shiels A. A new locus for dominant "zonular pulverulent" cataract, on chromosome 13. Am J Hum Genet. 1997 Jun;60(6):1474–1478. doi: 10.1086/515468. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mol B. W., van der Veen F., Redekop K., Bossuyt P. De waarde van de diagnostische tests bij infertiliteit. Ned Tijdschr Geneeskd. 1996 Feb 3;140(5):279–280. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muggleton-Harris A. L., Festing M. F., Hall M. A gene location for the inheritance of the cataract Fraser (CatFr) mouse congenital cataract. Genet Res. 1987 Jun;49(3):235–238. doi: 10.1017/s0016672300027129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oda S., Watanabe K., Fujisawa H., Kameyama Y. Impaired development of lens fibers in genetic microphthalmia, eye lens obsolescence, Elo, of the mouse. Exp Eye Res. 1980 Dec;31(6):673–681. doi: 10.1016/s0014-4835(80)80051-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Piatigorsky J. Multifunctional lens crystallins and corneal enzymes. More than meets the eye. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 1998 Apr 15;842:7–15. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1998.tb09626.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- RENWICK J. H., LAWLER S. D. PROBABLE LINKAGE BETWEEN A CONGENITAL CATARACT LOCUS AND THE DUFFY BLOOD GROUP LOCUS. Ann Hum Genet. 1963 Aug;27:67–84. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-1809.1963.tb00782.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rogaev E. I., Rogaeva E. A., Korovaitseva G. I., Farrer L. A., Petrin A. N., Keryanov S. A., Turaeva S., Chumakov I., St George-Hyslop P., Ginter E. K. Linkage of polymorphic congenital cataract to the gamma-crystallin gene locus on human chromosome 2q33-35. Hum Mol Genet. 1996 May;5(5):699–703. doi: 10.1093/hmg/5.5.699. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scott M. H., Hejtmancik J. F., Wozencraft L. A., Reuter L. M., Parks M. M., Kaiser-Kupfer M. I. Autosomal dominant congenital cataract. Interocular phenotypic variability. Ophthalmology. 1994 May;101(5):866–871. doi: 10.1016/s0161-6420(94)31246-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Semina E. V., Ferrell R. E., Mintz-Hittner H. A., Bitoun P., Alward W. L., Reiter R. S., Funkhauser C., Daack-Hirsch S., Murray J. C. A novel homeobox gene PITX3 is mutated in families with autosomal-dominant cataracts and ASMD. Nat Genet. 1998 Jun;19(2):167–170. doi: 10.1038/527. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shiels A., Bassnett S. Mutations in the founder of the MIP gene family underlie cataract development in the mouse. Nat Genet. 1996 Feb;12(2):212–215. doi: 10.1038/ng0296-212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shiels A., Mackay D., Ionides A., Berry V., Moore A., Bhattacharya S. A missense mutation in the human connexin50 gene (GJA8) underlies autosomal dominant "zonular pulverulent" cataract, on chromosome 1q. Am J Hum Genet. 1998 Mar;62(3):526–532. doi: 10.1086/301762. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sparkes R. S., Mohandas T., Heinzmann C., Gorin M. B., Horwitz J., Law M. L., Jones C. A., Bateman J. B. The gene for the major intrinsic protein (MIP) of the ocular lens is assigned to human chromosome 12cen-q14. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 1986 Sep;27(9):1351–1354. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wistow G. J., Lietman T., Williams L. A., Stapel S. O., de Jong W. W., Horwitz J., Piatigorsky J. Tau-crystallin/alpha-enolase: one gene encodes both an enzyme and a lens structural protein. J Cell Biol. 1988 Dec;107(6 Pt 2):2729–2736. doi: 10.1083/jcb.107.6.2729. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wistow G., Piatigorsky J. Recruitment of enzymes as lens structural proteins. Science. 1987 Jun 19;236(4808):1554–1556. doi: 10.1126/science.3589669. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Noort J. M., van Sechel A. C., Bajramovic J. J., el Ouagmiri M., Polman C. H., Lassmann H., Ravid R. The small heat-shock protein alpha B-crystallin as candidate autoantigen in multiple sclerosis. Nature. 1995 Jun 29;375(6534):798–801. doi: 10.1038/375798a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]