Abstract

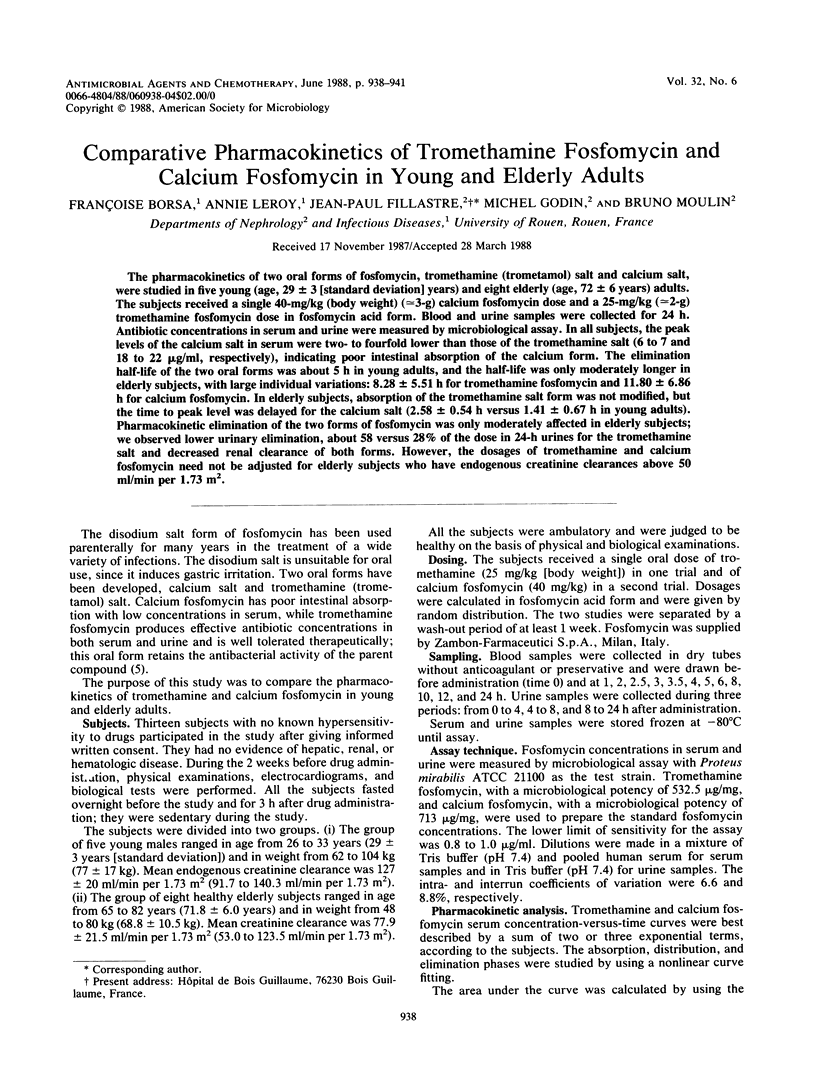

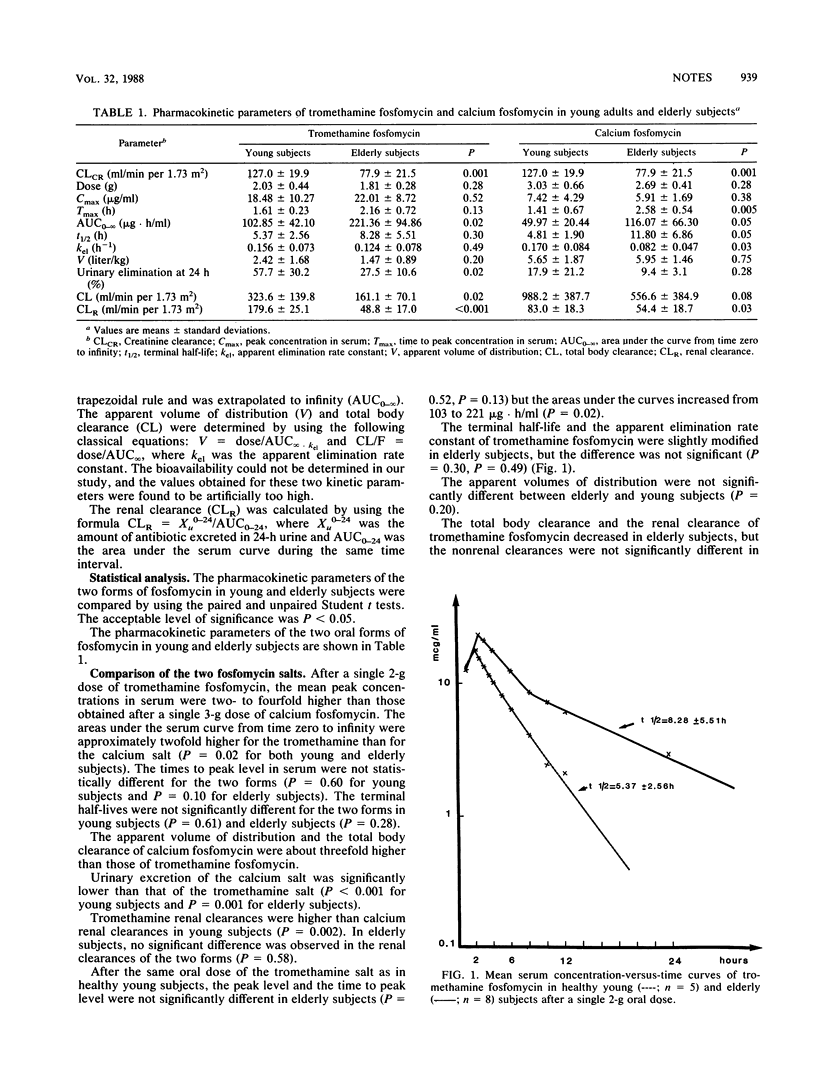

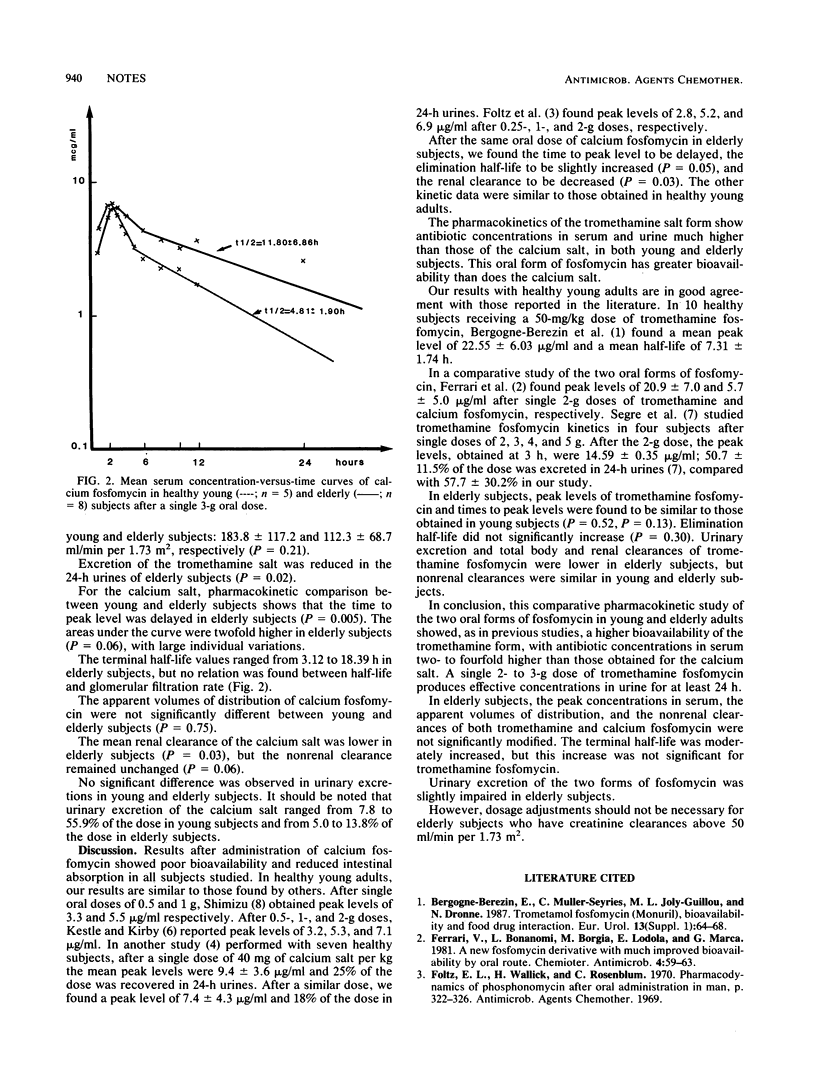

The pharmacokinetics of two oral forms of fosfomycin, tromethamine (trometamol) salt and calcium salt, were studied in five young (age, 29 +/- 3 [standard deviation] years) and eight elderly (age, 72 +/- 6 years) adults. The subjects received a single 40-mg/kg (body weight) (approximately equal to 3-g) calcium fosfomycin dose and a 25-mg/kg (approximately equal to 2-g) tromethamine fosfomycin dose in fosfomycin acid form. Blood and urine samples were collected for 24 h. Antibiotic concentrations in serum and urine were measured by microbiological assay. In all subjects, the peak levels of the calcium salt in serum were two- to fourfold lower than those of the tromethamine salt (6 to 7 and 18 to 22 micrograms/ml, respectively), indicating poor intestinal absorption of the calcium form. The elimination half-life of the two oral forms was about 5 h in young adults, and the half-life was only moderately longer in elderly subjects, with large individual variations: 8.28 +/- 5.51 h for tromethamine fosfomycin and 11.80 +/- 6.86 h for calcium fosfomycin. In elderly subjects, absorption of the tromethamine salt form was not modified, but the time to peak level was delayed for the calcium salt (2.58 +/- 0.54 h versus 1.41 +/- 0.67 h in young adults). Pharmacokinetic elimination of the two forms of fosfomycin was only moderately affected in elderly subjects; we observed lower urinary elimination, about 58 versus 28% of the dose in 24-h urines for the tromethamine salt and decreased renal clearance of both forms. However, the dosages of tromethamine and calcium fosfomycin need not be adjusted for elderly subjects who have endogenous creatinine clearances above 50 ml/min per 1.73 m2.

Full text

PDF

Selected References

These references are in PubMed. This may not be the complete list of references from this article.

- Barbieri C., Caldara R., Testori G., Piepoli V., Trezzi R., Romussi M., Ferrari C. Oral glucose tolerance and insulin response after one week's clonidine treatment in hypertensive patients. Acta Diabetol Lat. 1981;18(1):59–63. doi: 10.1007/BF02056107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bergogne-Bérézin E., Muller-Serieys C., Joly-Guillou M. L., Dronne N. Trometamol-fosfomycin (Monuril) bioavailability and food-drug interaction. Eur Urol. 1987;13 (Suppl 1):64–68. doi: 10.1159/000472865. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goto M., Sugiyama M., Nakajima S., Yamashina H. Fosfomycin kinetics after intravenous and oral administration to human volunteers. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1981 Sep;20(3):393–397. doi: 10.1128/aac.20.3.393. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greenwood D., Jones A., Eley A. Factors influencing the activity of the trometamol salt of fosfomycin. Eur J Clin Microbiol. 1986 Feb;5(1):29–34. doi: 10.1007/BF02013457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Segre G., Bianchi E., Cataldi A., Zannini G. Pharmacokinetic profile of fosfomycin trometamol (Monuril). Eur Urol. 1987;13 (Suppl 1):56–63. doi: 10.1159/000472864. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shimizu K. Fosfomycin: Absorption and excretion. Chemotherapy. 1977;23 (Suppl 1):153–158. doi: 10.1159/000222042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]