Abstract

BACKGROUND/AIMS—Androgens have been reported to influence the structural organisation, functional activity, and/or pathological features of many ocular tissues. In addition, these hormones have been proposed as a topical therapy for such conditions as dry eye syndromes, corneal wound healing, and high intraocular pressure. To advance our understanding of androgen action in the eye, the purpose of the present study was twofold: firstly, to determine whether tissues of the anterior and posterior segments contain androgen receptor protein, which might make them susceptible to hormone effects following topical application; and, secondly, to examine whether these tissues contain the mRNA for types 1 and/or 2 5α-reductase, an enzyme that converts testosterone to the very potent metabolite, dihydrotestosterone. METHODS—Human ocular tissues and cells were obtained and processed for histochemical and molecular biological procedures. Androgen receptor protein was identified by utilising specific immunoperoxidase techniques. The analysis of type 1 and type 2 5α-reductase mRNAs was performed by the use of RT-PCR, agarose gel electrophoresis, and DNA sequence analysis. All immunohistochemical evaluations and PCR amplifications included positive and negative controls. RESULTS—These findings show that androgen receptor protein exists in the human lacrimal gland, meibomian gland, cornea, bulbar and forniceal conjunctivae, lens epithelial cells, and retinal pigment epithelial cells. In addition, our results demonstrate that the mRNAs for types 1 and 2 5α-reductase occur in the human lacrimal gland, meibomian gland, bulbar conjunctiva, cornea, and RPE cells. CONCLUSION—These combined results indicate that multiple ocular tissues may be target sites for androgen action.

Full Text

The Full Text of this article is available as a PDF (247.4 KB).

Figure 1 .

Identification of androgen receptor protein in epithelial cell nuclei of the lacrimal gland. The tissue was obtained from an elderly man during ocular surgery and processed for immunoperoxidase procedures. To confirm the specificity of first antibody staining (A), an aliquot of the rabbit anti-human androgen receptor was preincubated with an excess amount of peptide "AR1-21" (B).

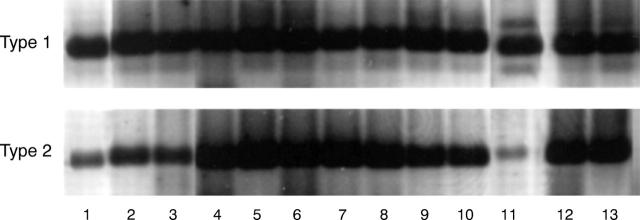

Figure 2 .

Presence of androgen receptor protein in the nuclei of acinar epithelial cells of the meibomian gland. The tissue was obtained from a 70 year old woman during plastic surgery for lid reconstruction. Immunoperoxidase staining of the tissue sample was performed with a first antibody that had been preincubated with either peptide "AR462-478" (A) or peptide "AR1-21" (B).

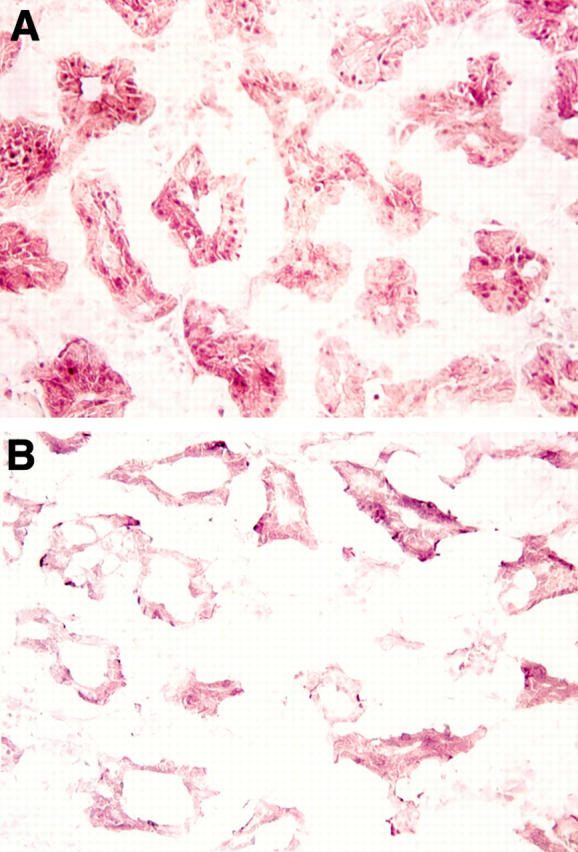

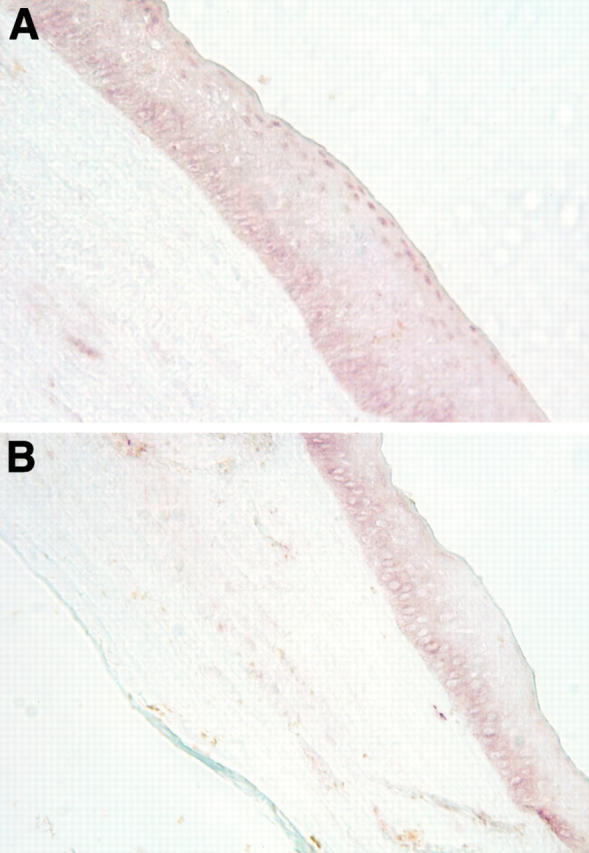

Figure 3 .

Location of androgen receptor protein in epithelial cell nuclei of the conjunctiva. The tissue was obtained from a 79 year old woman during an extracapsular crystalline extraction and then processed for immunoperoxidase procedures. To verify the specificity of first antibody staining (A), an aliquot of the rabbit anti-human androgen receptor was preincubated with an excess amount of peptide "AR1-21" (B).

Figure 4 .

Identification of androgen receptor protein in the nuclei of apical epithelial cells of the cornea. The tissue was obtained from a 65 year old woman during keratoplastic surgery. Immunoperoxidase analysis of the tissue sample was conducted with a first antibody that had been preincubated with either peptide "AR462-478" (A) or peptide "AR1-21" (B).

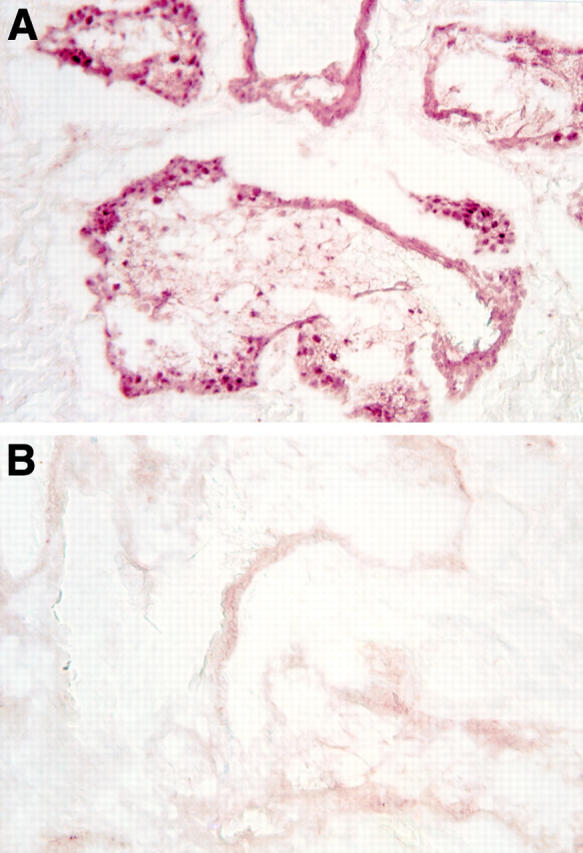

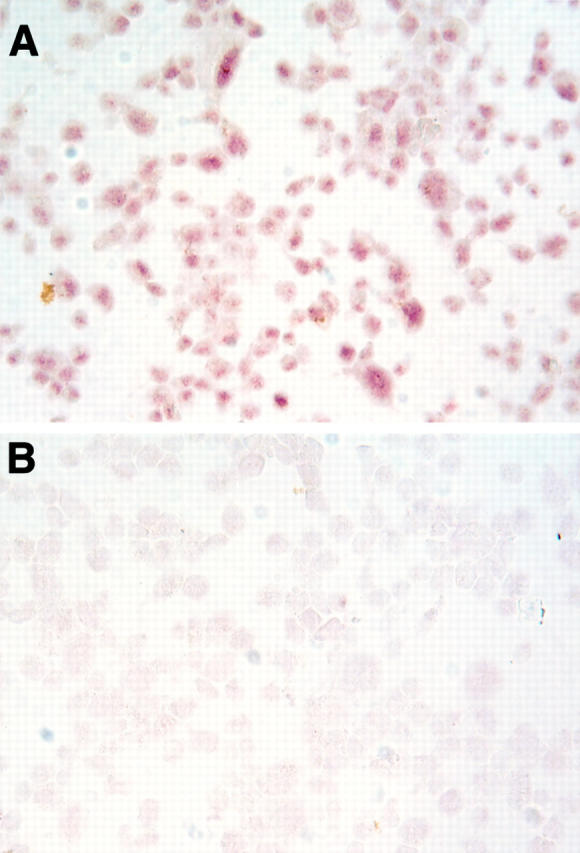

Figure 5 .

Presence of androgen receptor protein in the nuclei of lens epithelial cells. The lens cells were obtained from a 13 year old male undergoing cataract surgery and were then cultured, cytocentrifuged onto poly-L-lysine coated glass slides (105 cells/slide), fixed in acetone for 5 minutes at 4°C, and processed for immunoperoxidase procedures. Staining was performed with a first antibody that had been preincubated with either peptide "AR462-478" (A) or peptide "AR1-21" (B). Competition with this latter peptide resulted in background staining.

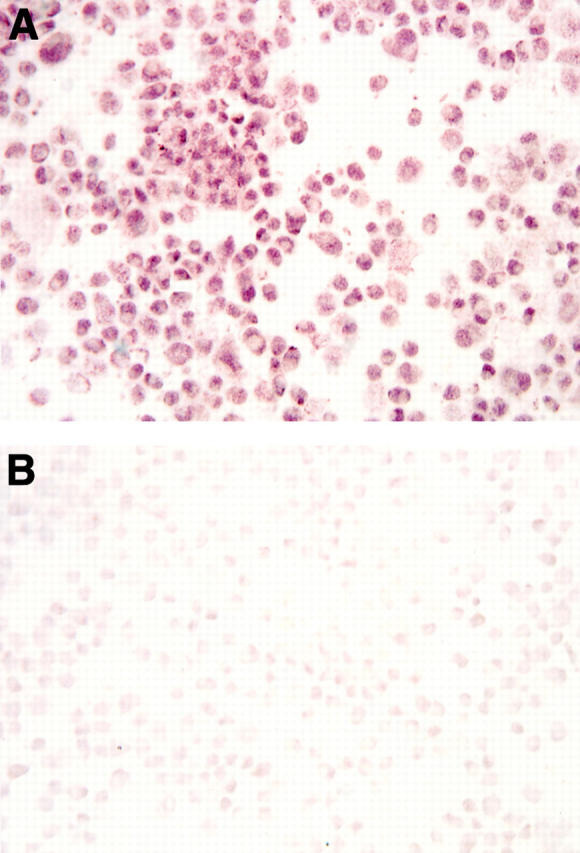

Figure 6 .

Identification of androgen receptor protein in the nuclei of retinal pigment epithelial cells. The cells were obtained from a 71 year old man following a cardiac arrest and were cultured until utilisation in this immunoperoxidase study. For analysis, cultured cells were cytocentrifuged onto poly-L-lysine coated glass slides (105 cells/slide), fixed in acetone for 5 minutes at 4°C, and then processed for receptor staining. To confirm the specificity of the first antibody staining (A), an aliquot of the rabbit anti-human androgen receptor was preincubated with an excess amount of peptide "AR1-21" (B).

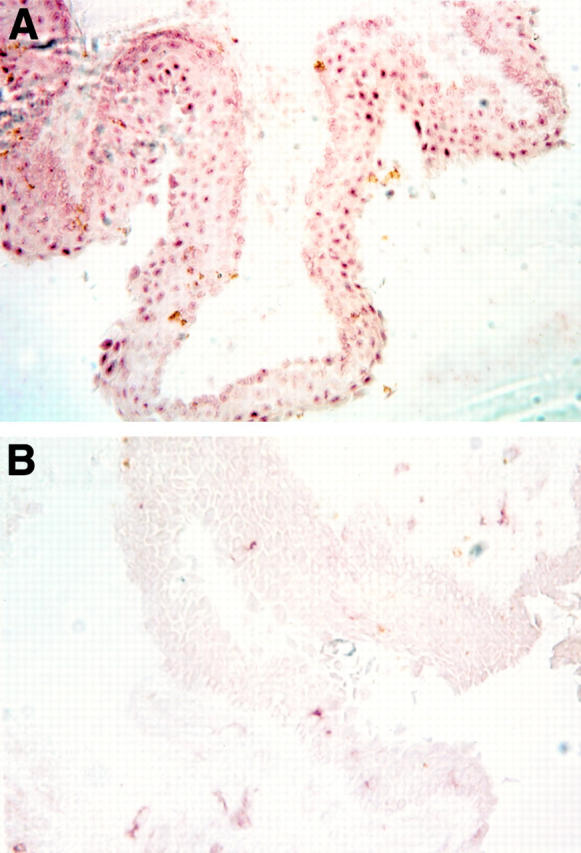

Figure 7 .

Presence of type 1 5α-reductase mRNA (Type 1) and type 2 5α-reductase mRNA (Type 2) in human ocular tissues and cells. Samples were processed for RT-PCR, agarose gel electrophoresis and ethidium bromide staining, as explained in Materials and methods. Photographs of agarose gels were obtained with a Polaroid camera (Polaroid Corporation, Cambridge, MA, USA) and images on the internegatives were then captured with a CCD-72S video camera (Hamamatsu Photonics, Japan), imported into Adobe Photoshop 4.01 and printed with a Kodak XLS 8600 printer. Samples 1-10 and 11-13 were run on parallel gels and bands have been aligned according to the molecular size of the bands. The numbers refer to the following samples: (1) male meibomian gland; (2) female meibomian gland; (3) female lacrimal gland; (4) male lacrimal gland; (5) prostate (surgical specimen); (6) Hs68 cells; (7) female conjunctiva (n = 3 combined tissues); (8) male conjunctiva (n = 3 combined tissues); (9) female cornea (n = 3 combined tissues); (10) male cornea (n = 3 combined tissues); (11) retinal pigment epithelial cells; (12) LNCaP cells; (13) prostate (RNA from Clontech).

Selected References

These references are in PubMed. This may not be the complete list of references from this article.

- Andersson S., Berman D. M., Jenkins E. P., Russell D. W. Deletion of steroid 5 alpha-reductase 2 gene in male pseudohermaphroditism. Nature. 1991 Nov 14;354(6349):159–161. doi: 10.1038/354159a0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andersson S., Russell D. W. Structural and biochemical properties of cloned and expressed human and rat steroid 5 alpha-reductases. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1990 May;87(10):3640–3644. doi: 10.1073/pnas.87.10.3640. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bayne C. W., Donnelly F., Chapman K., Bollina P., Buck C., Habib F. A novel coculture model for benign prostatic hyperplasia expressing both isoforms of 5 alpha-reductase. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1998 Jan;83(1):206–213. doi: 10.1210/jcem.83.1.4486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berthaut I., Mestayer C., Portois M. C., Cussenot O., Mowszowicz I. Pharmacological and molecular evidence for the expression of the two steroid 5 alpha-reductase isozymes in normal and hyperplastic human prostatic cells in culture. Prostate. 1997 Aug 1;32(3):155–163. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0045(19970801)32:3<155::aid-pros1>3.0.co;2-k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bird J., Li X., Lei Z. M., Sanfilippo J., Yussman M. A., Rao C. V. Luteinizing hormone and human chorionic gonadotropin decrease type 2 5 alpha-reductase and androgen receptor protein levels in women's skin. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1998 May;83(5):1776–1782. doi: 10.1210/jcem.83.5.4767. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brann D. W., Hendry L. B., Mahesh V. B. Emerging diversities in the mechanism of action of steroid hormones. J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol. 1995 Feb;52(2):113–133. doi: 10.1016/0960-0760(94)00160-n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Callard G. V., Kruger A., Betka M. The goldfish as a model for studying neuroestrogen synthesis, localization, and action in the brain and visual system. Environ Health Perspect. 1995 Oct;103 (Suppl 7):51–57. doi: 10.1289/ehp.95103s751. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Culig Z., Hobisch A., Cronauer M. V., Hittmair A., Radmayr C., Bartsch G., Klocker H. Activation of the androgen receptor by polypeptide growth factors and cellular regulators. World J Urol. 1995;13(5):285–289. doi: 10.1007/BF00185971. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Da Silva J. A., Larbre J. P., Seed M. P., Cutolo M., Villaggio B., Scott D. L., Willoughby D. A. Sex differences in inflammation induced cartilage damage in rodents. The influence of sex steroids. J Rheumatol. 1994 Feb;21(2):330–337. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guggenmoos-Holzmann I., Engel B., Henke V., Naumann G. O. Cell density of human lens epithelium in women higher than in men. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 1989 Feb;30(2):330–332. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guttridge N. M. Changes in ocular and visual variables during the menstrual cycle. Ophthalmic Physiol Opt. 1994 Jan;14(1):38–48. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-1313.1994.tb00555.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haffner S. M., Klein R., Dunn J. F., Moss S. E., Klein B. E. Increased testosterone in type I diabetic subjects with severe retinopathy. Ophthalmology. 1990 Oct;97(10):1270–1274. doi: 10.1016/s0161-6420(90)32428-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hahn J. D. Effect of cyproterone acetate on sexual dimorphism of the exorbital lacrimal gland in rats. J Endocrinol. 1969 Nov;45(3):421–424. doi: 10.1677/joe.0.0450421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hildebrandt P. G. Erfahrungen mit einer lokalen anabolen Therapie bei Hornhauterkrankungen. Med Monatsschr. 1974 Aug;28(8):359–360. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hiller R., Sperduto R. D., Ederer F. Epidemiologic associations with nuclear, cortical, and posterior subcapsular cataracts. Am J Epidemiol. 1986 Dec;124(6):916–925. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a114481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hirsch K. S., Jones C. D., Audia J. E., Andersson S., McQuaid L., Stamm N. B., Neubauer B. L., Pennington P., Toomey R. E., Russell D. W. LY191704: a selective, nonsteroidal inhibitor of human steroid 5 alpha-reductase type 1. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1993 Jun 1;90(11):5277–5281. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.11.5277. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Imperato-McGinley J., Gautier T., Cai L. Q., Yee B., Epstein J., Pochi P. The androgen control of sebum production. Studies of subjects with dihydrotestosterone deficiency and complete androgen insensitivity. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1993 Feb;76(2):524–528. doi: 10.1210/jcem.76.2.8381804. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kahn H. A., Leibowitz H. M., Ganley J. P., Kini M. M., Colton T., Nickerson R. S., Dawber T. R. The Framingham Eye Study. I. Outline and major prevalence findings. Am J Epidemiol. 1977 Jul;106(1):17–32. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a112428. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klein R., Klein B. E., Linton K. L., De Mets D. L. The Beaver Dam Eye Study: visual acuity. Ophthalmology. 1991 Aug;98(8):1310–1315. doi: 10.1016/s0161-6420(91)32137-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klein R., Klein B. E., Linton K. L. Prevalence of age-related maculopathy. The Beaver Dam Eye Study. Ophthalmology. 1992 Jun;99(6):933–943. doi: 10.1016/s0161-6420(92)31871-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klein R., Klein B. E., Moss S. E., Davis M. D., DeMets D. L. The Wisconsin epidemiologic study of diabetic retinopathy. II. Prevalence and risk of diabetic retinopathy when age at diagnosis is less than 30 years. Arch Ophthalmol. 1984 Apr;102(4):520–526. doi: 10.1001/archopht.1984.01040030398010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knepper P. A., Collins J. A., Frederick R. Effects of dexamethasone, progesterone, and testosterone on IOP and GAGs in the rabbit eye. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 1985 Aug;26(8):1093–1100. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Labrie F., Bélanger A., Cusan L., Candas B. Physiological changes in dehydroepiandrosterone are not reflected by serum levels of active androgens and estrogens but of their metabolites: intracrinology. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1997 Aug;82(8):2403–2409. doi: 10.1210/jcem.82.8.4161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Labrie F., Bélanger A., Cusan L., Gomez J. L., Candas B. Marked decline in serum concentrations of adrenal C19 sex steroid precursors and conjugated androgen metabolites during aging. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1997 Aug;82(8):2396–2402. doi: 10.1210/jcem.82.8.4160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Labrie F., Bélanger A., Simard J., Van Luu-The, Labrie C. DHEA and peripheral androgen and estrogen formation: intracinology. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 1995 Dec 29;774:16–28. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1995.tb17369.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Labrie F. Intracrinology. Mol Cell Endocrinol. 1991 Jul;78(3):C113–C118. doi: 10.1016/0303-7207(91)90116-a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lambert R. W., Kelleher R. S., Wickham L. A., Vaerman J. P., Sullivan D. A. Neuroendocrinimmune modulation of secretory component production by rat lacrimal, salivary, and intestinal epithelial cells. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 1994 Mar;35(3):1192–1201. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lanthier A., Patwardhan V. V. In vitro steroid metabolism by rat retina. Brain Res. 1988 Nov 1;463(2):403–406. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(88)90419-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Limonta P., Dondi D., Marelli M. M., Moretti R. M., Negri-Cesi P., Motta M. Growth of the androgen-dependent tumor of the prostate: role of androgens and of locally expressed growth modulatory factors. J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol. 1995 Jun;53(1-6):401–405. doi: 10.1016/0960-0760(95)00086-f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matsuzawa A., Wada E. Retarded and distinct progress of lens opacification in congenic hereditary cataract mice, Balb/c-nct/nct. Exp Eye Res. 1988 Nov;47(5):705–711. doi: 10.1016/0014-4835(88)90038-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mestayer C., Berthaut I., Portois M. C., Wright F., Kuttenn F., Mowszowicz I., Mauvais-Jarvis P. Predominant expression of 5 alpha-reductase type 1 in pubic skin from normal subjects and hirsute patients. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1996 May;81(5):1989–1993. doi: 10.1210/jcem.81.5.8626870. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moore R. J., Wilson J. D. Localization of the reduced nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide phosphate: 4 -3-ketosteroid 5 -oxidoreductase in the nuclear membrane of the rat ventral prostate. J Biol Chem. 1972 Feb 10;247(3):958–967. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Negri-Cesi P., Poletti A., Colciago A., Magni P., Martini P., Motta M. Presence of 5alpha-reductase isozymes and aromatase in human prostate cancer cells and in benign prostate hyperplastic tissue. Prostate. 1998 Mar 1;34(4):283–291. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0045(19980301)34:4<283::aid-pros6>3.0.co;2-i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ono M., Rocha F. J., Sullivan D. A. Immunocytochemical location and hormonal control of androgen receptors in lacrimal tissues of the female MRL/Mp-lpr/lpr mouse model of Sjögren's syndrome. Exp Eye Res. 1995 Dec;61(6):659–666. doi: 10.1016/s0014-4835(05)80016-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ota M., Kyakumoto S., Nemoto T. Demonstration and characterization of cytosol androgen receptor in rat exorbital lacrimal gland. Biochem Int. 1985 Feb;10(2):129–135. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ploc I., Stárka L. Testosterone binding in the cytosol of bovine corneal epithelium. Exp Eye Res. 1979 Jan;28(1):111–119. doi: 10.1016/0014-4835(79)90110-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Popper P., Farber D. B., Micevych P. E., Minoofar K., Bronstein J. M. TRPM-2 expression and tunel staining in neurodegenerative diseases: studies in wobbler and rd mice. Exp Neurol. 1997 Feb;143(2):246–254. doi: 10.1006/exnr.1996.6364. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prins G. S., Birch L., Greene G. L. Androgen receptor localization in different cell types of the adult rat prostate. Endocrinology. 1991 Dec;129(6):3187–3199. doi: 10.1210/endo-129-6-3187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rocha F. J., Wickham L. A., Pena J. D., Gao J., Ono M., Lambert R. W., Kelleher R. S., Sullivan D. A. Influence of gender and the endocrine environment on the distribution of androgen receptors in the lacrimal gland. J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol. 1993 Dec;46(6):737–749. doi: 10.1016/0960-0760(93)90314-m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rundlett S. E., Wu X. P., Miesfeld R. L. Functional characterizations of the androgen receptor confirm that the molecular basis of androgen action is transcriptional regulation. Mol Endocrinol. 1990 May;4(5):708–714. doi: 10.1210/mend-4-5-708. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schumacher H., Machemer R. Experimentelle Untersuchungen zur Therapie von Cortisonschäden der Kornea. Klin Monbl Augenheilkd. 1966;148(1):121–126. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Serrander A. M., Peek K. E. Changes in contact lens comfort related to the menstrual cycle and menopause. A review of articles. J Am Optom Assoc. 1993 Mar;64(3):162–166. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simental J. A., Sar M., Lane M. V., French F. S., Wilson E. M. Transcriptional activation and nuclear targeting signals of the human androgen receptor. J Biol Chem. 1991 Jan 5;266(1):510–518. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Southren A. L., Altman K., Vittek J., Boniuk V., Gordon G. G. Steroid metabolism in ocular tissues of the rabbit. Invest Ophthalmol. 1976 Mar;15(3):222–228. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stárka L., Obenberger J. In vitro estrone-estradiol-17beta interconversion in the cornea, lens, iris and retina of the rabbit eye. Albrecht Von Graefes Arch Klin Exp Ophthalmol. 1975 Aug 6;196(2):199–204. doi: 10.1007/BF00414806. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sullivan D. A., Bloch K. J., Allansmith M. R. Hormonal influence on the secretory immune system of the eye: androgen control of secretory component production by the rat exorbital gland. Immunology. 1984 Jun;52(2):239–246. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sullivan D. A., Edwards J. A., Wickham L. A., Pena J. D., Gao J., Ono M., Kelleher R. S. Identification and endocrine control of sex steroid binding sites in the lacrimal gland. Curr Eye Res. 1996 Mar;15(3):279–291. doi: 10.3109/02713689609007622. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sullivan D. A., Rocha E. M., Ullman M. D., Krenzer K. L., Gao J., Toda I., Dana M. R., Bazzinotti D., da Silveira L. A., Wickham L. A. Androgen regulation of the meibomian gland. Adv Exp Med Biol. 1998;438:327–331. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4615-5359-5_46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sullivan D. A. Sex hormones and Sjögren's syndrome. J Rheumatol Suppl. 1997 Sep;50:17–32. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sullivan D. A., Wickham L. A., Rocha E. M., Kelleher R. S., da Silveira L. A., Toda I. Influence of gender, sex steroid hormones, and the hypothalamic-pituitary axis on the structure and function of the lacrimal gland. Adv Exp Med Biol. 1998;438:11–42. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4615-5359-5_2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sullivan D. A., Wickham L. A., Rocha E. M., Krenzer K. L., Sullivan B. D., Steagall R., Cermak J. M., Dana M. R., Ullman M. D., Sato E. H. Androgens and dry eye in Sjögren's syndrome. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 1999 Jun 22;876:312–324. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1999.tb07656.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Toda I., Wickham L. A., Sullivan D. A. Gender and androgen treatment influence the expression of proto-oncogenes and apoptotic factors in lacrimal and salivary tissues of MRL/lpr mice. Clin Immunol Immunopathol. 1998 Jan;86(1):59–71. doi: 10.1006/clin.1997.4466. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsai T. H., Scheving L. E., Scheving L. A., Pauly J. E. Sex differences in circadian rhythms of several variables in lymphoreticular organs, liver, kidney, and corneal epithelium in adult CD2F1 mice. Anat Rec. 1985 Mar;211(3):263–270. doi: 10.1002/ar.1092110306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williamson J. R., Chang K., Tilton R. G., Prater C., Jeffrey J. R., Weigel C., Sherman W. R., Eades D. M., Kilo C. Increased vascular permeability in spontaneously diabetic BB/W rats and in rats with mild versus severe streptozocin-induced diabetes. Prevention by aldose reductase inhibitors and castration. Diabetes. 1987 Jul;36(7):813–821. doi: 10.2337/diab.36.7.813. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Winderickx J., Hemschoote K., De Clercq N., Van Dijck P., Peeters B., Rombauts W., Verhoeven G., Heyns W. Tissue-specific expression and androgen regulation of different genes encoding rat prostatic 22-kilodalton glycoproteins homologous to human and rat cystatin. Mol Endocrinol. 1990 Apr;4(4):657–667. doi: 10.1210/mend-4-4-657. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamamoto T., Terada N., Nishizawa Y., Petrow V. Angiostatic activities of medroxyprogesterone acetate and its analogues. Int J Cancer. 1994 Feb 1;56(3):393–399. doi: 10.1002/ijc.2910560318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]