Abstract

AIM—To review the clinical characteristics, diagnosis, and visual outcome in patients with non-contact lens related Acanthamoeba keratitis and compare the findings with reported series of contact lens associated Acanthamoeba keratitis. METHODS—Medical and microbiology records of 39 consecutive patients with a diagnosis of Acanthamoeba keratitis, at a tertiary eyecare centre in India between January 1996 and June 1998, were analysed retrospectively. RESULTS—A majority of the patients presented with poor visual acuity and large corneal stromal infiltrates (mean size 38.20 (SD 26.18) mm). A predisposing factor was elicited in 19/39 (48.7%) patients (trauma 15, dirty water splash three, leaf juice one). None of the patients had worn contact lenses. Most patients (26/39 (66.6%)) came from a low socioeconomic background. Complaint of severe pain was not a significant feature and radial keratoneuritis was seen in 1/39 (2.5%) patients. A ring infiltrate was present in 41.1% of cases. A clinical diagnosis of fungal keratitis was made in 45% of the patients before they were seen by us. However, all patients were diagnosed microbiologically at our institute based on demonstration of Acanthamoeba cysts in corneal scrapings (34/39) and/or culture of Acanthamoeba (34/39). Treatment with biguanides (PHMB, 15/38 (39.4%), PHMB with CHx, 23/38 (60.5%), one patient did not return for treatment) resulted in healing with scar formation in 27 out of 31(87.0%) followed up patients (mean time to healing 106.9 days). Overall visual outcome was poor with no statistical difference between cases diagnosed within 30 days (early) or 30 days after (late) start of symptoms. The visual outcome in cases requiring tissue adhesive (five) and keratoplasty (three) was also poor. CONCLUSIONS—This is thought to be the largest series of cases of Acanthamoeba keratitis in non-contact lens wearers. In such cases, the disease is advanced at presentation in most patients, pathognomonic clinical features are often not seen, disease progression is rapid, and visual outcome is usually poor. Possible existence of Acanthamoeba pathotypes specifically associated with non-contact lens keratitis and unique to certain geographical areas is suggested.

Full Text

The Full Text of this article is available as a PDF (130.9 KB).

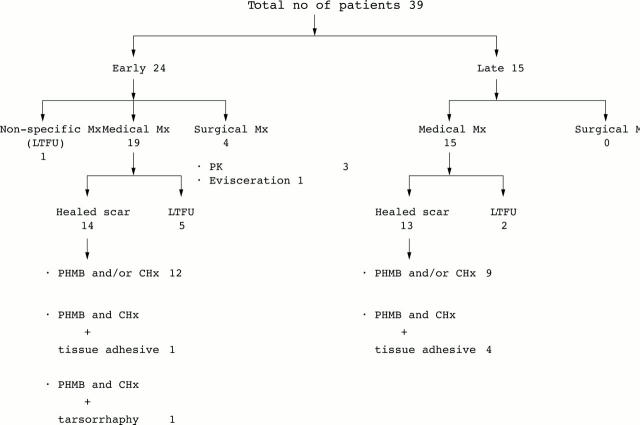

Figure 1 .

Therapeutic strategy and treatment outcome in 39 patients with non-contact lens related Acanthamoeba keratitis.

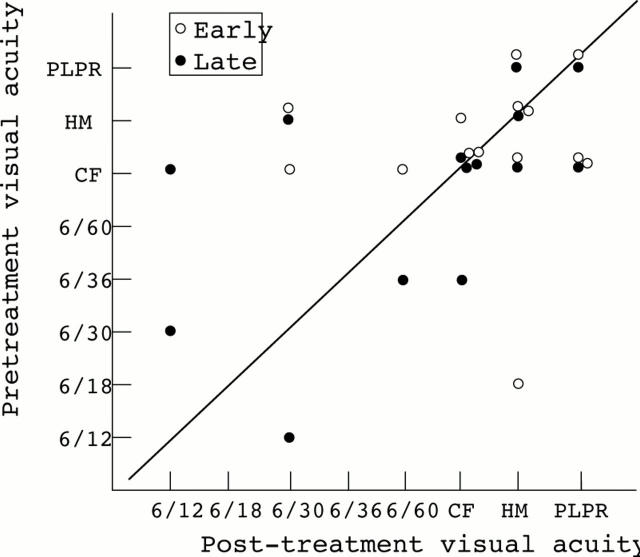

Figure 2 .

Pretreatment and post-treatment visual acuity in non-contact lens related Acanthamoeba keratitis patients diagnosed within 30 days (early, 14 cases) and 30 days after (late, 13 cases) start of symptoms.

Selected References

These references are in PubMed. This may not be the complete list of references from this article.

- Auran J. D., Starr M. B., Jakobiec F. A. Acanthamoeba keratitis. A review of the literature. Cornea. 1987;6(1):2–26. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buehler P. O., Schein O. D., Stamler J. F., Verdier D. D., Katz J. The increased risk of ulcerative keratitis among disposable soft contact lens users. Arch Ophthalmol. 1992 Nov;110(11):1555–1558. doi: 10.1001/archopht.1992.01080230055019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chynn E. W., Lopez M. A., Pavan-Langston D., Talamo J. H. Acanthamoeba keratitis. Contact lens and noncontact lens characteristics. Ophthalmology. 1995 Sep;102(9):1369–1373. doi: 10.1016/s0161-6420(95)30862-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collins C., Duff C., Duncan A. M., Planells-Cases R., Sun W., Norremolle A., Michaelis E., Montal M., Worton R., Hayden M. R. Mapping of the human NMDA receptor subunit (NMDAR1) and the proposed NMDA receptor glutamate-binding subunit (NMDARA1) to chromosomes 9q34.3 and chromosome 8, respectively. Genomics. 1993 Jul;17(1):237–239. doi: 10.1006/geno.1993.1311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dandona L., Dandona R., Naduvilath T. J., McCarty C. A., Nanda A., Srinivas M., Mandal P., Rao G. N. Is current eye-care-policy focus almost exclusively on cataract adequate to deal with blindness in India? Lancet. 1998 May 2;351(9112):1312–1316. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(97)09509-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duguid I. G., Dart J. K., Morlet N., Allan B. D., Matheson M., Ficker L., Tuft S. Outcome of acanthamoeba keratitis treated with polyhexamethyl biguanide and propamidine. Ophthalmology. 1997 Oct;104(10):1587–1592. doi: 10.1016/s0161-6420(97)30092-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Illingworth C. D., Cook S. D. Acanthamoeba keratitis. Surv Ophthalmol. 1998 May-Jun;42(6):493–508. doi: 10.1016/s0039-6257(98)00004-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kamel A. G., Norazah A. First case of Acanthamoeba keratitis in Malaysia. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 1995 Nov-Dec;89(6):652–652. doi: 10.1016/0035-9203(95)90429-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lindquist T. D. Treatment of Acanthamoeba keratitis. Cornea. 1998 Jan;17(1):11–16. doi: 10.1097/00003226-199801000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Niederkorn J. Y., Ubelaker J. E., McCulley J. P., Stewart G. L., Meyer D. R., Mellon J. A., Silvany R. E., He Y. G., Pidherney M., Martin J. H. Susceptibility of corneas from various animal species to in vitro binding and invasion by Acanthamoeba castellanii [corrected]. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 1992 Jan;33(1):104–112. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pettit D. A., Williamson J., Cabral G. A., Marciano-Cabral F. In vitro destruction of nerve cell cultures by Acanthamoeba spp.: a transmission and scanning electron microscopy study. J Parasitol. 1996 Oct;82(5):769–777. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prajna N. V., Pillai M. R., Manimegalai T. K., Srinivasan M. Use of Traditional Eye Medicines by corneal ulcer patients presenting to a hospital in South India. Indian J Ophthalmol. 1999 Mar;47(1):15–18. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Radford C. F., Bacon A. S., Dart J. K., Minassian D. C. Risk factors for acanthamoeba keratitis in contact lens users: a case-control study. BMJ. 1995 Jun 17;310(6994):1567–1570. doi: 10.1136/bmj.310.6994.1567. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Radford C. F., Lehmann O. J., Dart J. K. Acanthamoeba keratitis: multicentre survey in England 1992-6. National Acanthamoeba Keratitis Study Group. Br J Ophthalmol. 1998 Dec;82(12):1387–1392. doi: 10.1136/bjo.82.12.1387. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schaumberg D. A., Snow K. K., Dana M. R. The epidemic of Acanthamoeba keratitis: where do we stand? Cornea. 1998 Jan;17(1):3–10. doi: 10.1097/00003226-199801000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sharma S., Srinivasan M., George C. Acanthamoeba keratitis in non-contact lens wearers. Arch Ophthalmol. 1990 May;108(5):676–678. doi: 10.1001/archopht.1990.01070070062035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singh S., Sachdeva M. P. Acanthamoeba keratitis. BMJ. 1994 Jul 23;309(6949):273–273. doi: 10.1136/bmj.309.6949.273. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Srinivasan M., Channa P., Raju C. V., George C. Acanthamoeba keratitis in hard contact lens wearer. Indian J Ophthalmol. 1993 Dec;41(4):187–188. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Srinivasan M., Gonzales C. A., George C., Cevallos V., Mascarenhas J. M., Asokan B., Wilkins J., Smolin G., Whitcher J. P. Epidemiology and aetiological diagnosis of corneal ulceration in Madurai, south India. Br J Ophthalmol. 1997 Nov;81(11):965–971. doi: 10.1136/bjo.81.11.965. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stehr-Green J. K., Bailey T. M., Brandt F. H., Carr J. H., Bond W. W., Visvesvara G. S. Acanthamoeba keratitis in soft contact lens wearers. A case-control study. JAMA. 1987 Jul 3;258(1):57–60. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stehr-Green J. K., Bailey T. M., Visvesvara G. S. The epidemiology of Acanthamoeba keratitis in the United States. Am J Ophthalmol. 1989 Apr 15;107(4):331–336. doi: 10.1016/0002-9394(89)90654-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tay-Kearney M. L., McGhee C. N., Crawford G. J., Trown K. Acanthamoeba keratitis. A masquerade of presentation in six cases. Aust N Z J Ophthalmol. 1993 Nov;21(4):237–245. doi: 10.1111/j.1442-9071.1993.tb00962.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tirado-Angel J., Gabriel M. M., Wilson L. A., Ahearn D. G. Effects of polyhexamethylene biguanide and chlorhexidine on four species of Acanthamoeba in vitro. Curr Eye Res. 1996 Feb;15(2):225–228. doi: 10.3109/02713689608997418. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whitcher J. P., Srinivasan M. Corneal ulceration in the developing world--a silent epidemic. Br J Ophthalmol. 1997 Aug;81(8):622–623. doi: 10.1136/bjo.81.8.622. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilhelmus K. R., Osato M. S., Font R. L., Robinson N. M., Jones D. B. Rapid diagnosis of Acanthamoeba keratitis using calcofluor white. Arch Ophthalmol. 1986 Sep;104(9):1309–1312. doi: 10.1001/archopht.1986.01050210063026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]