Abstract

AIM—To describe the prevalence of and risk factors for pterygium in a population based sample of residents of the Australian state of Victoria who were aged 40 years and older. METHODS—The strata comprised nine randomly selected clusters from the Melbourne statistical division, 14 nursing homes randomly selected from the nursing homes within a 5 kilometre radius of the nine Melbourne clusters, and four randomly selected clusters from rural Victoria. Pterygium was measured in millimetres from the tip to the middle of the base. During an interview, people were queried about previous ocular surgery, including surgical removal of pterygium, and their lifetime exposure to sunlight. RESULTS—5147 people participated. They ranged in age from 40 to 101 years and 2850 (55.4%) were female. Only one person in the Melbourne cohort reported previous pterygium surgery, and seven rural residents reported previous surgery; this information was unavailable for the nursing home residents. Pterygium was present upon clinical examination in 39 (1.2%) of the 3229 Melbourne residents who had the clinical examination, six (1.7%) of the nursing home residents, and 96 (6.7%) of the rural residents. The overall weighted population rate in the population was 2.83% (95% CL 2.35, 3.31). The independent risk factors for pterygium were found to be age (OR=1.23, 95% CL=1.06, 1.44), male sex (OR=2.02, 95% CL=1.35, 3.03), rural residence (OR=5.28, 95% CL=3.56, 7.84), and lifetime ocular sun exposure (OR=1.63, 95% CL=1.18, 2.25). The attributable risk of sunlight and pterygium was 43.6% (95% CL=42.7, 44.6). The result was the same when ocular UV-B exposure was substituted in the model for broad band sun exposure. CONCLUSION—Pterygium is a significant public health problem in rural areas, primarily as a result of ocular sun exposure.

Full Text

The Full Text of this article is available as a PDF (123.0 KB).

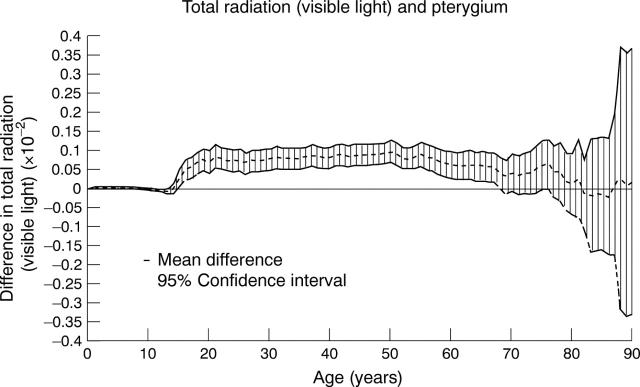

Figure 1 .

Mean difference in ocular sun exposure between pterygium cases and controls at each year of life.

Selected References

These references are in PubMed. This may not be the complete list of references from this article.

- Coroneo M. T. Albedo concentration in the anterior eye: a phenomenon that locates some solar diseases. Ophthalmic Surg. 1990 Jan;21(1):60–66. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coroneo M. T., Müller-Stolzenburg N. W., Ho A. Peripheral light focusing by the anterior eye and the ophthalmohelioses. Ophthalmic Surg. 1991 Dec;22(12):705–711. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coroneo M. T. Pterygium as an early indicator of ultraviolet insolation: a hypothesis. Br J Ophthalmol. 1993 Nov;77(11):734–739. doi: 10.1136/bjo.77.11.734. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coster D. Pterygium--an ophthalmic enigma. Br J Ophthalmol. 1995 Apr;79(4):304–305. doi: 10.1136/bjo.79.4.304. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Detels R., Dhir S. P. Pterygium: a geographical study. Arch Ophthalmol. 1967 Oct;78(4):485–491. doi: 10.1001/archopht.1967.00980030487014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dhir S. P., Detels R., Alexander E. R. The role of environmental factors in cataract, pterygium and trachoma. Am J Ophthalmol. 1967 Jul;64(1):128–135. doi: 10.1016/0002-9394(67)93353-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duncan D. D., Muñoz B., Bandeen-Roche K., West S. K. Visible and ultraviolet-B ocular-ambient exposure ratios for a general population. Salisbury Eye Evaluation Project Team. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 1997 Apr;38(5):1003–1011. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hirst L. W., Sebban A., Chant D. Pterygium recurrence time. Ophthalmology. 1994 Apr;101(4):755–758. doi: 10.1016/s0161-6420(94)31270-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karukonda S. R., Thompson H. W., Beuerman R. W., Lam D. S., Wilson R., Chew S. J., Steinemann T. L. Cell cycle kinetics in pterygium at three latitudes. Br J Ophthalmol. 1995 Apr;79(4):313–317. doi: 10.1136/bjo.79.4.313. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Livingston P. M., Carson C. A., Stanislavsky Y. L., Lee S. E., Guest C. S., Taylor H. R. Methods for a population-based study of eye disease: the Melbourne Visual Impairment Project. Ophthalmic Epidemiol. 1994 Dec;1(3):139–148. doi: 10.3109/09286589409047222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Livingston P. M., Lee S. E., McCarty C. A., Taylor H. R. A comparison of participants with non-participants in a population-based epidemiologic study: the Melbourne Visual Impairment Project. Ophthalmic Epidemiol. 1997 Jun;4(2):73–81. doi: 10.3109/09286589709057099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mackenzie F. D., Hirst L. W., Battistutta D., Green A. Risk analysis in the development of pterygia. Ophthalmology. 1992 Jul;99(7):1056–1061. doi: 10.1016/s0161-6420(92)31850-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCarty C. A., Lee S. E., Livingston P. M., Bissinella M., Taylor H. R. Ocular exposure to UV-B in sunlight: the Melbourne visual impairment project model. Bull World Health Organ. 1996;74(4):353–360. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCarty C. A., Taylor H. R. Protecting eyes from sun damage. Med J Aust. 1997 Jun 16;166(12):671–671. doi: 10.5694/j.1326-5377.1997.tb123318.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCarty C. A., Taylor H. R. Recent developments in vision research: light damage in cataract. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 1996 Aug;37(9):1720–1723. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moran D. J., Hollows F. C. Pterygium and ultraviolet radiation: a positive correlation. Br J Ophthalmol. 1984 May;68(5):343–346. doi: 10.1136/bjo.68.5.343. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Panchapakesan J., Hourihan F., Mitchell P. Prevalence of pterygium and pinguecula: the Blue Mountains Eye Study. Aust N Z J Ophthalmol. 1998 May;26 (Suppl 1):S2–S5. doi: 10.1111/j.1442-9071.1998.tb01362.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosenthal F. S., Bakalian A. E., Lou C. Q., Taylor H. R. The effect of sunglasses on ocular exposure to ultraviolet radiation. Am J Public Health. 1988 Jan;78(1):72–74. doi: 10.2105/ajph.78.1.72. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith A. H., Waxweiler R. J., Tyroler H. A. Epidemiologic investigation of occupational carcinogenesis using a serially additive expected dose model. Am J Epidemiol. 1980 Dec;112(6):787–797. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a113051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor H. R. Aetiology of climatic droplet keratopathy and pterygium. Br J Ophthalmol. 1980 Mar;64(3):154–163. doi: 10.1136/bjo.64.3.154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor H. R., West S. K., Rosenthal F. S., Munoz B., Newland H. S., Emmett E. A. Corneal changes associated with chronic UV irradiation. Arch Ophthalmol. 1989 Oct;107(10):1481–1484. doi: 10.1001/archopht.1989.01070020555039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]