Abstract

BACKGROUND/AIMS—Regulation of plasmin mediated extracellular matrix degradation by vascular endothelial cells is important in the development of angiogenesis. The aim was to determine whether transforming growth factor β (TGF-β) affected the regulation of components of the plasminogen system by human retinal endothelial cells, in order to define more clearly the role of TGF-β in retinal angiogenesis in the context of diabetes mellitus. METHODS—Human retinal endothelial cells (HREC) were isolated from donor eyes and used between passages 4-8. The cells were cultured in medium supplemented with 2, 5, 15, or 25 mM glucose, plus or minus TGF-β (1 ng/ml). The concentrations of tissue plasminogen activator (t-PA), urokinase plasminogen activator (u-PA), and plasminogen activator inhibitor type 1 (PAI-1) in cell conditioned medium were determined by ELISA and the level of PAI-1 mRNA was determined using northern hybridisation. Cell associated plasminogen activity was determined using a clot lysis assay and a chromogenic assay. RESULTS—Under basal conditions (5 mM glucose), HREC produced PAI-1, t-PA, and trace amounts of u-PA. Cell surface plasminogen activation observed by lysis of fibrin or by cleavage of chromogenic substrate, was mediated by t-PA. Glucose at varying concentrations (2-25 mM) had no significant effect on t-PA mediated clot lysis. In contrast, treatment with TGF-β resulted in increased synthesis of PAI-1 protein and mRNA. The increased expression of the PAI-1 mRNAs by TGF-β did not occur uniformly, the 2.3 kb mRNA transcript was preferentially increased in comparison with the 3.2 kb mRNA (p<0.05). CONCLUSIONS—These data demonstrate that TGF-β increases PAI-1 and decreases cell associated lysis. This is sufficient to decrease the normal lytic potential of HREC.

Full Text

The Full Text of this article is available as a PDF (233.7 KB).

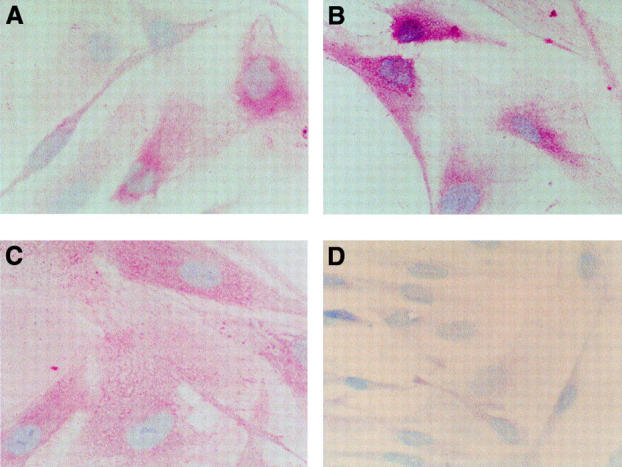

Figure 1 .

Immunohistochemical detection of u-PA, t-PA, and PAI-1 in human retinal endothelial cells. The detection of u-PA, t-PA, and PAI-1 was carried out using the APAAP method with HREC cultured in 5 mM glucose, 2.5% PDS in chamber slides. Positive staining was evident as pink coloration in the cytoplasm with u-PA (A), t-PA (B), and PAI-1 (C). A negative control is shown (D) (original magnification ×895).

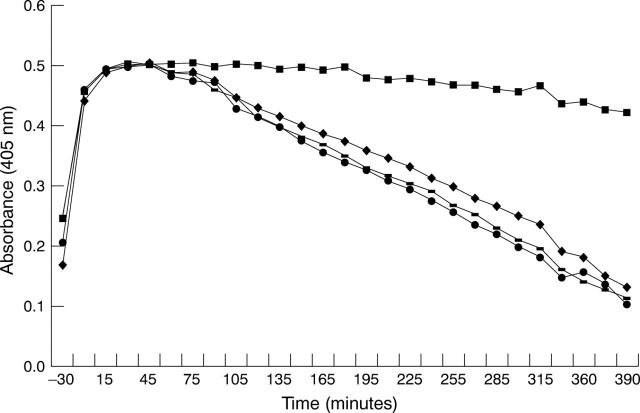

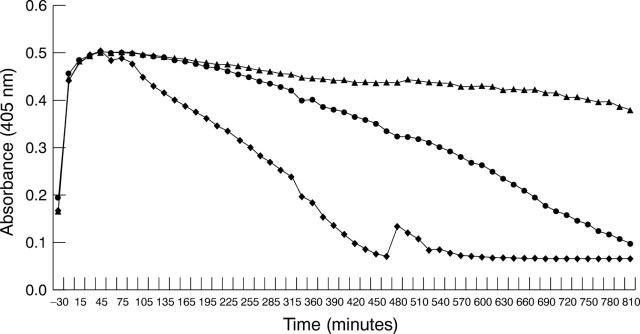

Figure 2 .

Fibrin clot lysis by HREC. Standard clots, which were prepared with either no antibodies (♦) or antibodies to u-PA(-), t-PA(▪), and PAI-1(•), were overlaid on monolayers of HREC, pretreated in serum free containing medium supplemented with 5 mM glucose for 24 hours. Results are representative of three experiments using HREC from different donors. The presence of antibodies to t-PA significantly inhibited clot lysis.

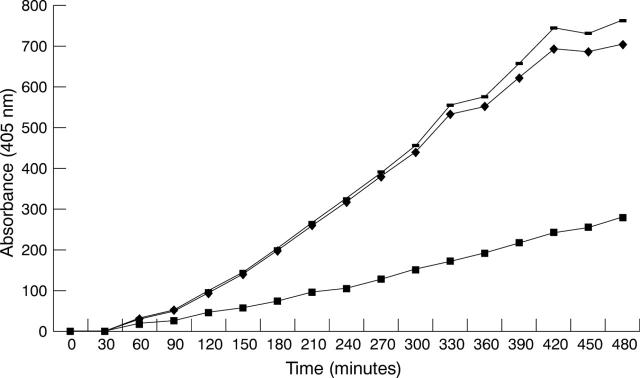

Figure 3 .

Chromogenic detection of t-PA activity. Monolayers of HREC pretreated for 24 hours in serum free GMEM were incubated with plasminogen and S2251. Incorporation of anti-t-PA (▪) significantly reduced the generation of the colour while anti-u-PA (−) had no effect. A negative control using normal rabbit serum (⧫) is included for comparison.

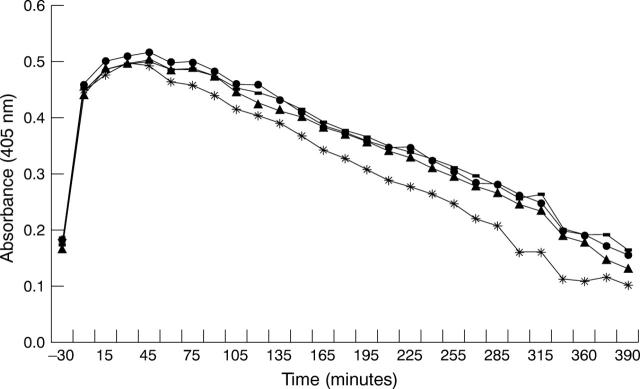

Figure 4 .

Effects of glucose on HREC fibrin clot lysis. Standard fibrin clots were prepared and overlaid on monolayers of HREC pretreated for 24 hours in serum free containing medium supplemented with 2 (•), 5(−), 15(*), or 25(▴) mM glucose. Results are representative of three experiments using HREC from different donors. The rate of clot lysis did not change when the cells were incubated in different glucose concentrations.

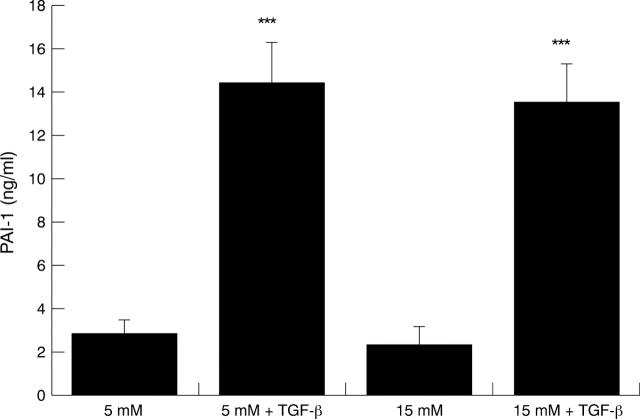

Figure 5 .

TGF-β mediated increased expression of PAI-1 by HREC. HREC were stepped down overnight in serum free glucose free GMEM and then the medium was replaced with 5 or 15 mM glucose plus or minus TGF-β (1 ng/ml) for 24 hours. Results are the mean (SD) of six samples from one experiment and are representative of four experiments using HREC from different donors. Increased levels of PAI-1 antigen were evident when the cells were incubated with TGF-β as determined by a two tailed Student's t test (***p<0.001).

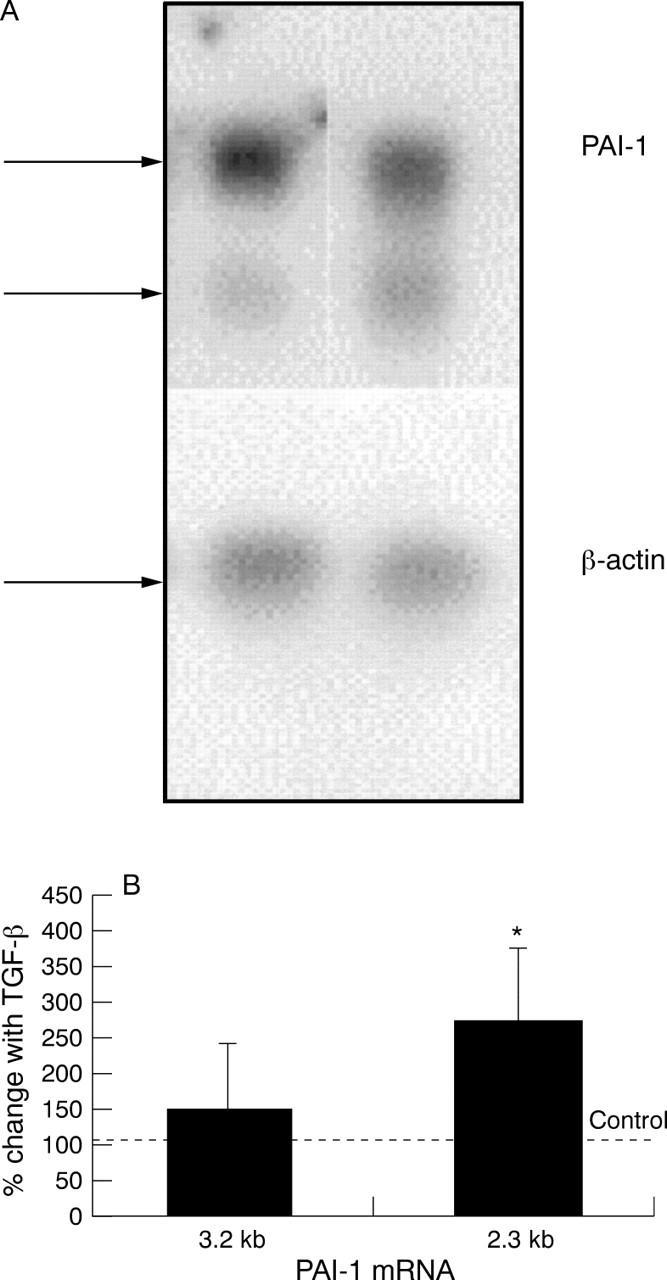

Figure 6 .

Effect of TGF-β on the level of PAI-1 mRNA. HREC were stepped down overnight in serum free glucose free GMEM. The medium was then replaced with serum free GMEM supplemented with 5 mM glucose plus or minus TGF-β (1 ng/ml). After 6 hours' incubation the cells were harvested and total RNA was extracted. Northern hybridisation indicated the presence of two PAI-1 specific mRNA bands (3.2 bp and 2.3 bp) and β-actin mRNA (A). The mRNA was quantified and is presented as the mean (SD) of the ratio of the respective PAI-1 transcripts with the level of β-actin mRNA with data from three separate experiments (B). The results were compared to a value of 100%—that is, the level of PAI-1 mRNA in the absence of TGF-β using a one tailed Student's t test (*p<0.05).

Figure 7 .

Effects of TGF-β treated HREC on fibrin clot lysis. HRECs, pretreated in serum free containing medium with either 5 mM glucose (♦) or 5 mM glucose plus TGF-β (1 ng/ml (▴) for 24 hours, were overlaid with fibrin. Antibody to PAI-1 was incorporated in the fibrin overlay of the TGF-β treated HREC (•). Results are representative of three experiments using different donors. The presence of TGF-β increased the rate of clot lysis and this effect was partially inhibited by the presence of antibody to PAI-1.

Selected References

These references are in PubMed. This may not be the complete list of references from this article.

- Alder V. A., Su E. N., Yu D. Y., Cringle S. J., Yu P. K. Diabetic retinopathy: early functional changes. Clin Exp Pharmacol Physiol. 1997 Sep-Oct;24(9-10):785–788. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1681.1997.tb02133.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ashton N. Vascular basement membrane changes in diabetic retinopathy. Montgomery lecture, 1973. Br J Ophthalmol. 1974 Apr;58(4):344–366. doi: 10.1136/bjo.58.4.344. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baricos W. H., Cortez S. L., Deboisblanc M., Xin S. Transforming growth factor-beta is a potent inhibitor of extracellular matrix degradation by cultured human mesangial cells. J Am Soc Nephrol. 1999 Apr;10(4):790–795. doi: 10.1681/ASN.V104790. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baudouin C., Fredj-Reygrobellet D., Lapalus P., Gastaud P. Immunohistopathologic findings in proliferative diabetic retinopathy. Am J Ophthalmol. 1988 Apr 15;105(4):383–388. doi: 10.1016/0002-9394(88)90302-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Booth N. A., MacGregor I. R., Hunter N. R., Bennett B. Plasminogen activator inhibitor from human endothelial cells. Purification and partial characterization. Eur J Biochem. 1987 Jun 15;165(3):595–600. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1987.tb11481.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boulton M., Gregor Z., McLeod D., Charteris D., Jarvis-Evans J., Moriarty P., Khaliq A., Foreman D., Allamby D., Bardsley B. Intravitreal growth factors in proliferative diabetic retinopathy: correlation with neovascular activity and glycaemic management. Br J Ophthalmol. 1997 Mar;81(3):228–233. doi: 10.1136/bjo.81.3.228. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cagliero E., Roth T., Taylor A. W., Lorenzi M. The effects of high glucose on human endothelial cell growth and gene expression are not mediated by transforming growth factor-beta. Lab Invest. 1995 Nov;73(5):667–673. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Canfield A. E., Schor A. M., Loskutoff D. J., Schor S. L., Grant M. E. Plasminogen activator inhibitor-type I is a major biosynthetic product of retinal microvascular endothelial cells and pericytes in culture. Biochem J. 1989 Apr 15;259(2):529–535. doi: 10.1042/bj2590529. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chmielewska J., Wiman B. Determination of tissue plasminogen activator and its "fast" inhibitor in plasma. Clin Chem. 1986 Mar;32(3):482–485. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chomczynski P., Sacchi N. Single-step method of RNA isolation by acid guanidinium thiocyanate-phenol-chloroform extraction. Anal Biochem. 1987 Apr;162(1):156–159. doi: 10.1006/abio.1987.9999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- D'Amore P. A. Mechanisms of retinal and choroidal neovascularization. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 1994 Nov;35(12):3974–3979. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elias A. N., Pandian M. R., Naqvi F., Sebag J., Charles M. A., Gwinup G. Relationship between prorenin, IGF-I, IGF-binding proteins and retinopathy in diabetic patients. Gen Pharmacol. 1996 Mar;27(2):329–332. doi: 10.1016/0306-3623(95)02033-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fattal P. G., Schneider D. J., Sobel B. E., Billadello J. J. Post-transcriptional regulation of expression of plasminogen activator inhibitor type 1 mRNA by insulin and insulin-like growth factor 1. J Biol Chem. 1992 Jun 25;267(18):12412–12415. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Forrester J. V., Shafiee A., Schröder S., Knott R., McIntosh L. The role of growth factors in proliferative diabetic retinopathy. Eye (Lond) 1993;7(Pt 2):276–287. doi: 10.1038/eye.1993.61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ginsburg D., Zeheb R., Yang A. Y., Rafferty U. M., Andreasen P. A., Nielsen L., Dano K., Lebo R. V., Gelehrter T. D. cDNA cloning of human plasminogen activator-inhibitor from endothelial cells. J Clin Invest. 1986 Dec;78(6):1673–1680. doi: 10.1172/JCI112761. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grant M. B., Ellis E. A., Caballero S., Mames R. N. Plasminogen activator inhibitor-1 overexpression in nonproliferative diabetic retinopathy. Exp Eye Res. 1996 Sep;63(3):233–244. doi: 10.1006/exer.1996.0112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grant M. B., Guay C. Plasminogen activator production by human retinal endothelial cells of nondiabetic and diabetic origin. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 1991 Jan;32(1):53–64. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hua X., Liu X., Ansari D. O., Lodish H. F. Synergistic cooperation of TFE3 and smad proteins in TGF-beta-induced transcription of the plasminogen activator inhibitor-1 gene. Genes Dev. 1998 Oct 1;12(19):3084–3095. doi: 10.1101/gad.12.19.3084. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ignotz R. A., Massagué J. Transforming growth factor-beta stimulates the expression of fibronectin and collagen and their incorporation into the extracellular matrix. J Biol Chem. 1986 Mar 25;261(9):4337–4345. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ito K., Ryuto M., Ushiro S., Ono M., Sugenoya A., Kuraoka A., Shibata Y., Kuwano M. Expression of tissue-type plasminogen activator and its inhibitor couples with development of capillary network by human microvascular endothelial cells on Matrigel. J Cell Physiol. 1995 Feb;162(2):213–224. doi: 10.1002/jcp.1041620207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knott R. M., Robertson M., Forrester J. V. Regulation of glucose transporter (GLUT 3) and aldose reductase mRNA inbovine retinal endothelial cells and retinal pericytes in high glucose and high galactose culture. Diabetologia. 1993 Sep;36(9):808–812. doi: 10.1007/BF00400354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knott R. M., Robertson M., Muckersie E., Forrester J. V. Regulation of glucose transporters (GLUT-1 and GLUT-3) in human retinal endothelial cells. Biochem J. 1996 Aug 15;318(Pt 1):313–317. doi: 10.1042/bj3180313. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levin E. G., Santell L., Osborn K. G. The expression of endothelial tissue plasminogen activator in vivo: a function defined by vessel size and anatomic location. J Cell Sci. 1997 Jan;110(Pt 2):139–148. doi: 10.1242/jcs.110.2.139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu G., Takano T., Amino N. TGF-beta 1 inhibits the cell proliferation stimulated by IGF-I by blocking the tyrosine phosphorylation of 175kDa substrate. Endocr Res. 1996 Aug;22(3):277–287. doi: 10.3109/07435809609030512. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacGregor I. R., Booth N. A. An enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) used to study the cellular secretion of endothelial plasminogen activator inhibitor (PAI-1). Thromb Haemost. 1988 Feb 25;59(1):68–72. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacGregor I. R., Micklem L. R., James K., Pepper D. S. Characterisation of epitopes on human tissue plasminogen activator recognised by a group of monoclonal antibodies. Thromb Haemost. 1985 Feb 18;53(1):45–50. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maiello M., Boeri D., Podesta F., Cagliero E., Vichi M., Odetti P., Adezati L., Lorenzi M. Increased expression of tissue plasminogen activator and its inhibitor and reduced fibrinolytic potential of human endothelial cells cultured in elevated glucose. Diabetes. 1992 Aug;41(8):1009–1015. doi: 10.2337/diab.41.8.1009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Massagué J. The transforming growth factor-beta family. Annu Rev Cell Biol. 1990;6:597–641. doi: 10.1146/annurev.cb.06.110190.003121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nagi D. K., McCormack L. J., Mohamed-Ali V., Yudkin J. S., Knowler W. C., Grant P. J. Diabetic retinopathy, promoter (4G/5G) polymorphism of PAI-1 gene, and PAI-1 activity in Pima Indians with type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Care. 1997 Aug;20(8):1304–1309. doi: 10.2337/diacare.20.8.1304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nielsen D. A., Shapiro D. J. Insights into hormonal control of messenger RNA stability. Mol Endocrinol. 1990 Jul;4(7):953–957. doi: 10.1210/mend-4-7-953. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ostermann H., Tschöpe D., Greber W., Meyer-Rüsenberg H. W., van de Loo J. Enhancement of spontaneous fibrinolytic activity in diabetic retinopathy. Thromb Haemost. 1992 Oct 5;68(4):400–403. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pascal M. M., Forrester J. V., Knott R. M. Glucose-mediated regulation of transforming growth factor-beta (TGF-beta) and TGF-beta receptors in human retinal endothelial cells. Curr Eye Res. 1999 Aug;19(2):162–170. doi: 10.1076/ceyr.19.2.162.5332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patel B., Hiscott P., Charteris D., Mather J., McLeod D., Boulton M. Retinal and preretinal localisation of epidermal growth factor, transforming growth factor alpha, and their receptor in proliferative diabetic retinopathy. Br J Ophthalmol. 1994 Sep;78(9):714–718. doi: 10.1136/bjo.78.9.714. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pfeiffer A., Middelberg-Bisping K., Drewes C., Schatz H. Elevated plasma levels of transforming growth factor-beta 1 in NIDDM. Diabetes Care. 1996 Oct;19(10):1113–1117. doi: 10.2337/diacare.19.10.1113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pfeiffer A., Spranger J., Meyer-Schwickerath R., Schatz H. Growth factor alterations in advanced diabetic retinopathy: a possible role of blood retina barrier breakdown. Diabetes. 1997 Sep;46 (Suppl 2):S26–S30. doi: 10.2337/diab.46.2.s26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ritchie H., Jamieson A., Booth N. A. Thrombin modulates synthesis of plasminogen activator inhibitor type 2 by human peripheral blood monocytes. Blood. 1995 Nov 1;86(9):3428–3435. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ritchie H., Robbie L. A., Kinghorn S., Exley R., Booth N. A. Monocyte plasminogen activator inhibitor 2 (PAI-2) inhibits u-PA-mediated fibrin clot lysis and is cross-linked to fibrin. Thromb Haemost. 1999 Jan;81(1):96–103. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robbie L. A., Bennett B., Croll A. M., Brown P. A., Booth N. A. Proteins of the fibrinolytic system in human thrombi. Thromb Haemost. 1996 Jan;75(1):127–133. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sawdey M., Podor T. J., Loskutoff D. J. Regulation of type 1 plasminogen activator inhibitor gene expression in cultured bovine aortic endothelial cells. Induction by transforming growth factor-beta, lipopolysaccharide, and tumor necrosis factor-alpha. J Biol Chem. 1989 Jun 25;264(18):10396–10401. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sehested M., Hou-Jensen K. Factor VII related antigen as an endothelial cell marker in benign and malignant diseases. Virchows Arch A Pathol Anat Histol. 1981;391(2):217–225. doi: 10.1007/BF00437598. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spranger J., Meyer-Schwickerath R., Klein M., Schatz H., Pfeiffer A. Deficient activation and different expression of transforming growth factor-beta isoforms in active proliferative diabetic retinopathy and neovascular eye disease. Exp Clin Endocrinol Diabetes. 1999;107(1):21–28. doi: 10.1055/s-0029-1212068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- The relationship of glycemic exposure (HbA1c) to the risk of development and progression of retinopathy in the diabetes control and complications trial. Diabetes. 1995 Aug;44(8):968–983. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vaag A., Hother-Nielsen O., Skött P., Andersen P., Richter E. A., Beck-Nielsen H. Effect of acute hyperglycemia on glucose metabolism in skeletal muscles in IDDM patients. Diabetes. 1992 Feb;41(2):174–182. doi: 10.2337/diab.41.2.174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wiedemann P. Growth factors in retinal diseases: proliferative vitreoretinopathy, proliferative diabetic retinopathy, and retinal degeneration. Surv Ophthalmol. 1992 Mar-Apr;36(5):373–384. doi: 10.1016/0039-6257(92)90115-a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilson H. M., Reid F. J., Brown P. A., Power D. A., Haites N. E., Booth N. A. Effect of transforming growth factor-beta 1 on plasminogen activators and plasminogen activator inhibitor-1 in renal glomerular cells. Exp Nephrol. 1993 Nov-Dec;1(6):343–350. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang J., Ren S., Sun D., Shen G. X. Influence of glycation on LDL-induced generation of fibrinolytic regulators in vascular endothelial cells. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 1998 Jul;18(7):1140–1148. doi: 10.1161/01.atv.18.7.1140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]