Abstract

AIM—To determine the most reliable and consistent method and time interval over which to implement a vision impairment quality of life assessment tool. METHODS—117 patients with low vision aged 9-101 years were assigned into three age, sex, and visual function matched groups (n = 39 in each) to answer the Low Vision Quality of Life (LVQOL) questionnaire by post, telephone, or in person. The LVQOL questionnaire was completed on four occasions, each separated by four weeks. RESULTS—Postal implementation was the most cost effective method, showed the highest internal consistency of LVQOL items, but resulted in a lower apparent quality of life score than either telephone or in-person interviews (p<0.001). There was no difference in test-retest reliability between the three methods of implementation (p = 0.12). The profile of LVQOL scores showed a trend towards reduced quality of life scores 3 months after the baseline measures, although this was not significant. CONCLUSION—Posting may be the method of choice for clinical measurement of vision related quality of life. Patients with greater visual impairment were no less likely to complete a questionnaire when implemented by post and there was no apparent bias from other people assisting them. The quality of life measure can occur at any time up to 2 months after low vision rehabilitation for the progressive nature of conditions causing low vision not to cause a decreased baseline score. The LVQOL was shown to be a highly internally consistent and reliable method for measuring quality of life in the visually impaired.

Full Text

The Full Text of this article is available as a PDF (135.5 KB).

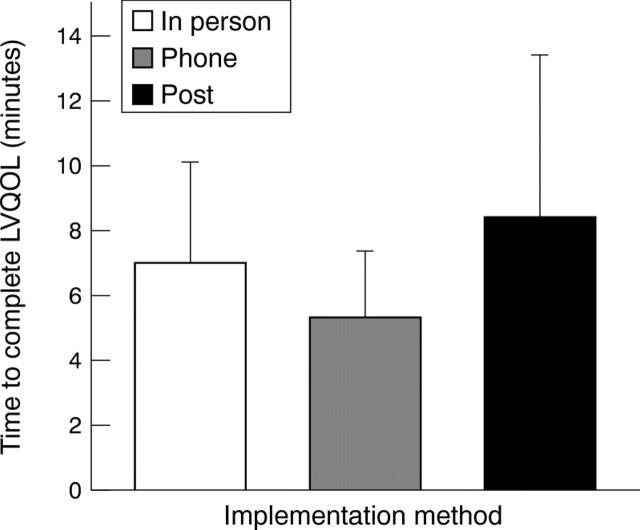

Figure 1 .

(A) Staff time and (B) consumable costs of implementing the LVQOL questionnaire by post (n=39), telephone (n=39), or in person (n=39) interviews. Postal implementation was the most cost effective method.

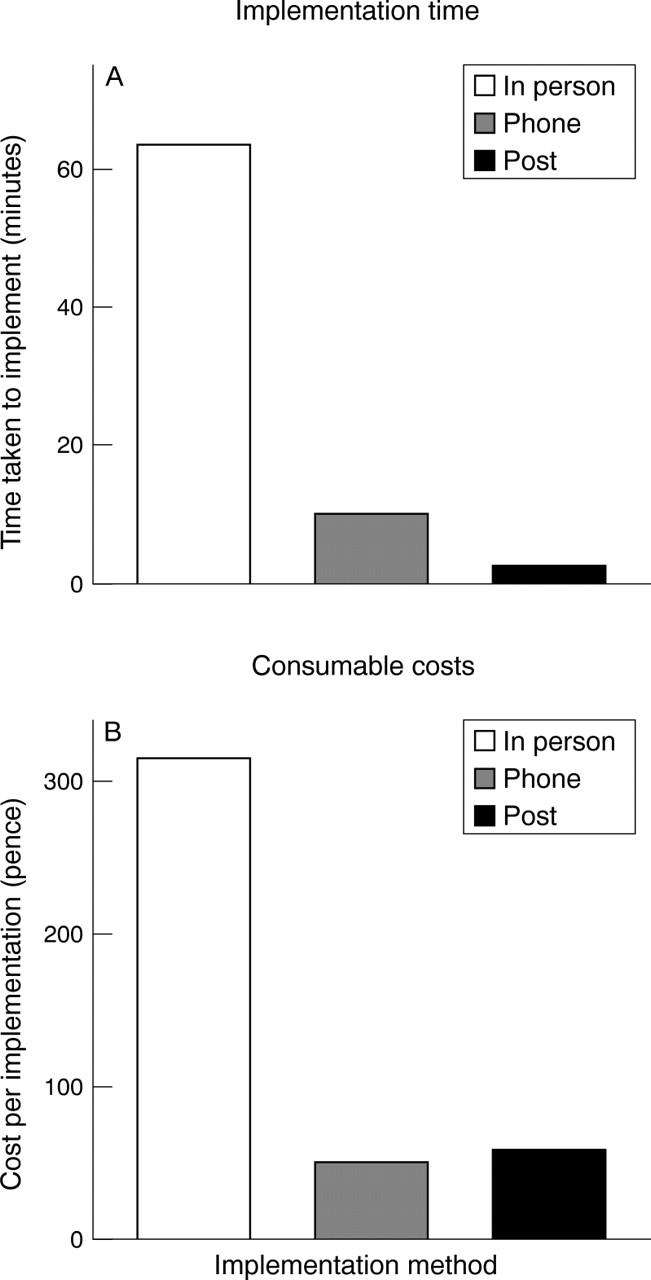

Figure 2 .

Time taken for visually impaired patients to complete the LVQOL questionnaire by post (n=39), by telephone (n=39), or by in-person (n=39) interviews. Telephone implementation was significantly faster. Error bars = 1 SD.

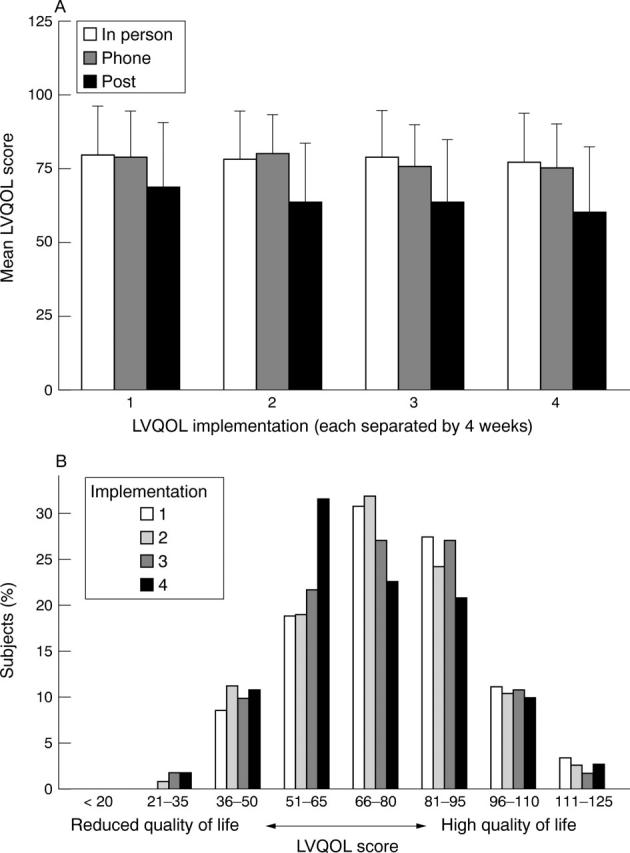

Figure 3 .

(A) Mean summed score for the LVQOL questionnaire over a 3 month period by post (n=39), by telephone (n=39), or by in-person (n=39) interviews. There was no significant difference in scores over this time period, but those completing the questionnaire by post had an apparently lower quality of life. Error bars = 1 SD. (B) Distribution of summed LVQOL scores over a 3 month period. There was a decrease in apparent LVQOL score 3 months after the initial implementation, but this was not found to be significant (n=117).

Selected References

These references are in PubMed. This may not be the complete list of references from this article.

- Abrahamsson M., Carlsson B., Törnqvist M., Sterner B., Sjöstrand J. Changes of visual function and visual ability in daily life following cataract surgery. Acta Ophthalmol Scand. 1996 Feb;74(1):69–73. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0420.1996.tb00686.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bailey I. L., Lovie J. E. New design principles for visual acuity letter charts. Am J Optom Physiol Opt. 1976 Nov;53(11):740–745. doi: 10.1097/00006324-197611000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carta A., Braccio L., Belpoliti M., Soliani L., Sartore F., Gandolfi S. A., Maraini G. Self-assessment of the quality of vision: association of questionnaire score with objective clinical tests. Curr Eye Res. 1998 May;17(5):506–511. doi: 10.1076/ceyr.17.5.506.5191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cleary P. A., Beck R. W., Bourque L. B., Backlund J. C., Miskala P. H. Visual symptoms after optic neuritis. Results from the Optic Neuritis Treatment Trial. J Neuroophthalmol. 1997 Mar;17(1):18–28. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9394(14)70814-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elliott D. B., Hurst M. A., Weatherill J. Comparing clinical tests of visual function in cataract with the patient's perceived visual disability. Eye (Lond) 1990;4(Pt 5):712–717. doi: 10.1038/eye.1990.100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ellwein L. B., Fletcher A., Negrel A. D., Thulasiraj R. D. Quality of life assessment in blindness prevention interventions. Int Ophthalmol. 1994;18(5):263–268. doi: 10.1007/BF00917828. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Faubert J., Overbury O. Active-passive paradigm in assessing CCTV-aided reading. Am J Optom Physiol Opt. 1987 Jan;64(1):23–28. doi: 10.1097/00006324-198701000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frost N. A., Sparrow J. M., Durant J. S., Donovan J. L., Peters T. J., Brookes S. T. Development of a questionnaire for measurement of vision-related quality of life. Ophthalmic Epidemiol. 1998 Dec;5(4):185–210. doi: 10.1076/opep.5.4.185.4191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greeves A. L., Cole B. L., Jacobs R. J. Reliability and validity of simple photographic plate tests of contrast sensitivity. Am J Optom Physiol Opt. 1987 Nov;64(11):832–841. doi: 10.1097/00006324-198711000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gutierrez P., Wilson M. R., Johnson C., Gordon M., Cioffi G. A., Ritch R., Sherwood M., Meng K., Mangione C. M. Influence of glaucomatous visual field loss on health-related quality of life. Arch Ophthalmol. 1997 Jun;115(6):777–784. doi: 10.1001/archopht.1997.01100150779014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harper R., Doorduyn K., Reeves B., Slater L. Evaluating the outcomes of low vision rehabilitation. Ophthalmic Physiol Opt. 1999 Jan;19(1):3–11. doi: 10.1046/j.1475-1313.1999.00411.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leat S. J., Rumney N. J. The experience of a university-based low vision clinic. Ophthalmic Physiol Opt. 1990 Jan;10(1):8–15. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lundström M., Roos P., Jensen S., Fregell G. Catquest questionnaire for use in cataract surgery care: description, validity, and reliability. J Cataract Refract Surg. 1997 Oct;23(8):1226–1236. doi: 10.1016/s0886-3350(97)80321-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mangione C. M., Lee P. P., Pitts J., Gutierrez P., Berry S., Hays R. D. Psychometric properties of the National Eye Institute Visual Function Questionnaire (NEI-VFQ). NEI-VFQ Field Test Investigators. Arch Ophthalmol. 1998 Nov;116(11):1496–1504. doi: 10.1001/archopht.116.11.1496. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mangione C. M., Phillips R. S., Seddon J. M., Lawrence M. G., Cook E. F., Dailey R., Goldman L. Development of the 'Activities of Daily Vision Scale'. A measure of visual functional status. Med Care. 1992 Dec;30(12):1111–1126. doi: 10.1097/00005650-199212000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parrish R. K., 2nd Visual impairment, visual functioning, and quality of life assessments in patients with glaucoma. Trans Am Ophthalmol Soc. 1996;94:919–1028. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ross J. E., Bron A. J., Clarke D. D. Contrast sensitivity and visual disability in chronic simple glaucoma. Br J Ophthalmol. 1984 Nov;68(11):821–827. doi: 10.1136/bjo.68.11.821. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]