Abstract

AIM—To identify if laser photocoagulation induces morphological changes specifically related to the choroidal capillary endothelial processes that protrude into Bruch's membrane. METHODS—Two human eyes and one adult macaque monkey eye received retinal laser photocoagulation that was just suprathreshold, before enucleation or exenteration. They were examined by electron microscopy to determine the length of the endothelial processes emanating from the choroidal capillaries in the region around the laser burn. One human and two monkey untreated eyes were used for comparison. RESULTS—In human eyes, there was no increase in the number of processes 15 hours after laser treatment but at 5 days the processes were more numerous and longer within 400-500 µm of the burn than in the untreated half of the same eye. The processes were longer 9 days after photocoagulation in the monkey, when compared with untreated monkeys, and some breached the elastic lamina, a phenomenon not seen in the untreated eyes. Qualitative differences were also noted in the endothelial cell processes following photocoagulation. Neovascularisation was not observed. CONCLUSIONS—Protrusion of choroidal endothelial cell processes into Bruch's membrane is a normal anatomical feature but the number, length, and morphology of the processes change following mild photocoagulation. It is plausible that these processes may play a part in the clearance of debris from Bruch's membrane, and represent an early stage of angiogenesis. If the latter is true prophylactic laser photocoagulation at just suprathreshold levels may carry a risk of inducing choroidal neovascularisation.

Full Text

The Full Text of this article is available as a PDF (292.2 KB).

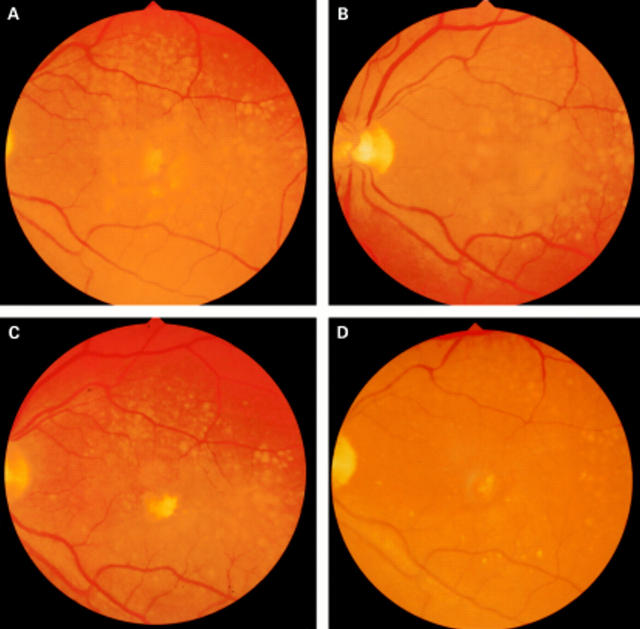

Figure 1 .

Fundus photographs of a patient who received prophylactic photocoagulation treatment for high risk drusen. (A) Before treatment with 12 spots ×200 µm ×0.2 seconds at a power to just whiten the retina. The lesions are placed in a ring 1000 µm from the fovea; (B) 3 months after photocoagulation; (C) 6 months after photocoagulation; (D) 20 months after photocoagulation. Note that the clearance starts around the area of the laser burns and spreads out circumferentially and that the effect is continuing at 20 months.

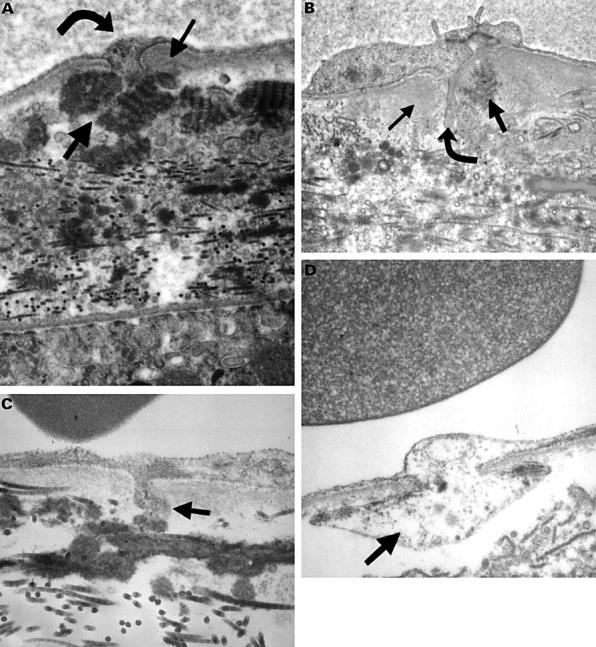

Figure 2 .

Electron micrograph of choriocapillaris and Bruch's membrane in human eyes. (A) An untreated area of patient 3 (final magnification 48 000), and (B) an 71 year old man (final magnification 50 000). These show focal thickening of basal lamina (small arrow) around the base of a cell process (curved arrow) associated with long spacing collagen (LSC) (thick arrow) in the outer collagenous zone (OCZ). (C) 22 year old man (final magnification 100 000), (D) an 82 year old woman (final magnification 80 000); these show a magnified appearance of the processes (thick arrow).

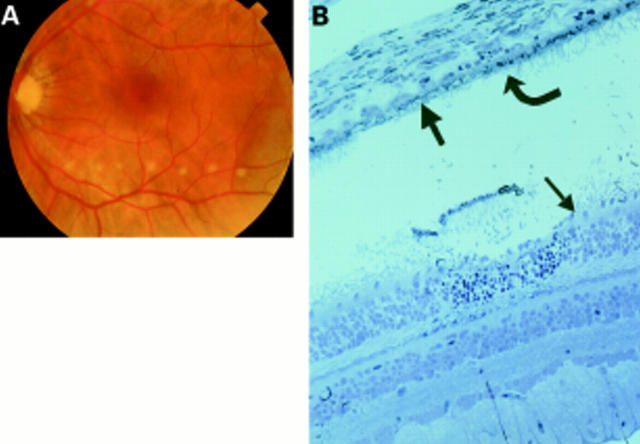

Figure 3 .

Patient 2 treated 15 hours before exenteration. (A) Colour fundus photograph of the laser burns taken minutes after they were created. (B) Histology of the laser burn. The burn is localised to the photoreceptors (small arrow) and RPE (curved arrow), with Bruch's membrane (thick arrow) still intact and most of the choriocapillaris surviving.

Figure 4 .

Patient 3 lasered 5 days before exenteration. (A) Colour fundus photograph of the laser burns taken minutes after they were created. (B) Histology of the laser burn. The burn is localised to the photoreceptors (small arrow) and RPE (curved arrow), with Bruch's membrane (thick arrow) still intact and most of the choriocapillaris surviving.

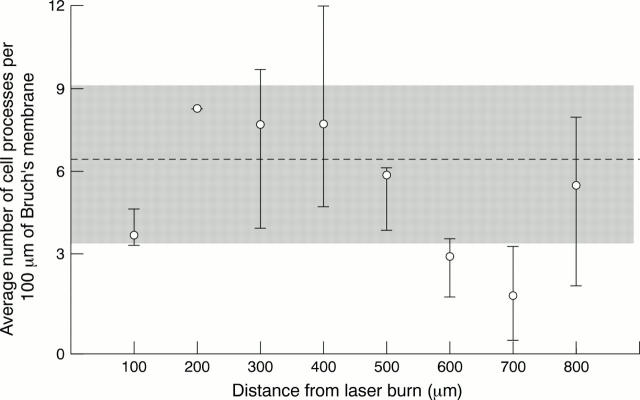

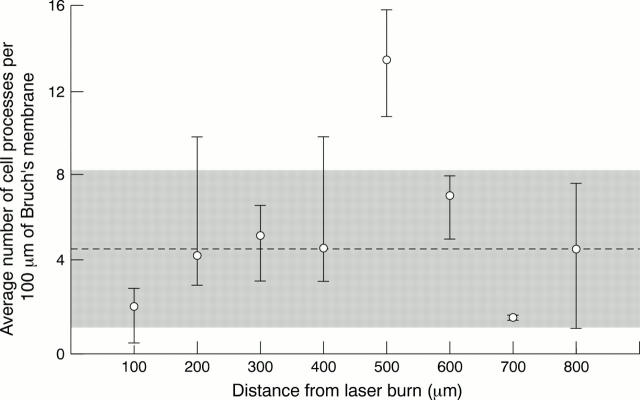

Figure 5 .

Graph of the average number of processes per 100 µm of Bruch's membrane against the distance from the laser burn in patient 2. Patient 2 received laser treatment 15 hours before exenteration. The shaded area represents the range in the number of processes seen in the untreated half of patient 2's retina. The broken line is the average number seen per 100 µm.

Figure 6 .

Graph of the average number of processes per 100 µm of Bruch's membrane against the distance from the laser burn in patient 3. There were 5 days between photocoagulation and exenteration. The shaded area represents the range in the number of processes seen in the untreated half of patient 3's retina. The broken line is the average number seen per 100 µm. Note the increase in number of processes 400-500 µm from the laser burn.

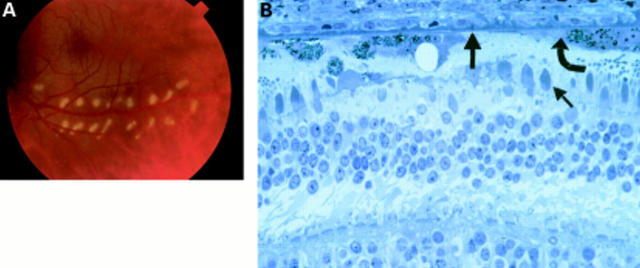

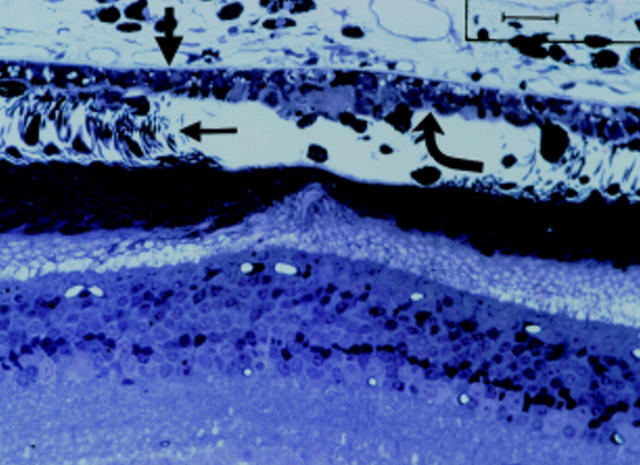

Figure 7 .

Monkey eye after photocoagulation. Histology of the laser burn. The burn is localised to the photoreceptors (small arrow) and RPE (curved arrow), with Bruch's membrane still intact (thick arrow) and most of the choriocapillaris surviving.

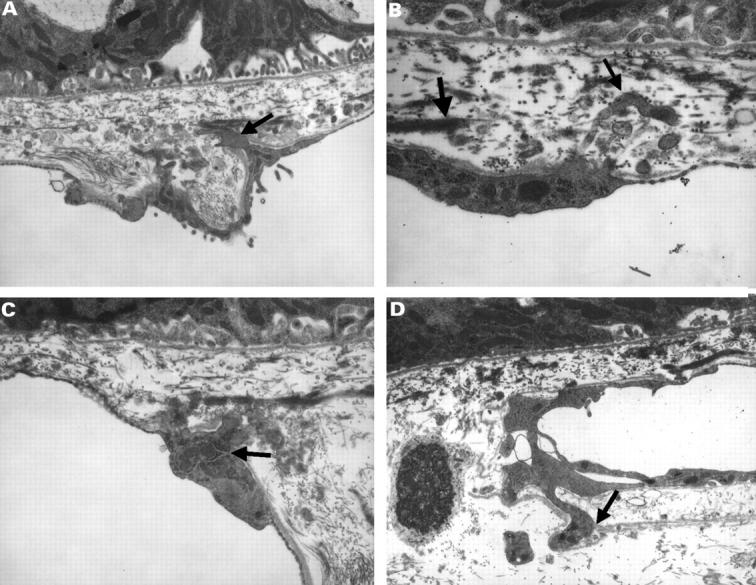

Figure 8 .

(A) Electron micrograph of a monkey's Bruch's membrane and choriocapillaris showing endothelial processes (small arrow) (final magnification 40 000) and (B) electron micrograph showing a process (small arrow) protruding through the elastic lamina of Bruch's membrane (thick arrow) (final magnification 80 000). (C) Electron micrograph in which the endothelial cell appears to have an increase in cytoplasmic organelles (small arrow) (final magnification 48 000), and (D) electron micrograph with processes displacing the basal lamina (small arrow) of the endothelial cell (final magnification 32 000).

Selected References

These references are in PubMed. This may not be the complete list of references from this article.

- Ausprunk D. H., Folkman J. Migration and proliferation of endothelial cells in preformed and newly formed blood vessels during tumor angiogenesis. Microvasc Res. 1977 Jul;14(1):53–65. doi: 10.1016/0026-2862(77)90141-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cleasby G. W., Nakanishi A. S., Norris J. L. Prophylactic photocoagulation of the fellow eye in exudative senile maculopathy. A preliminary report. Mod Probl Ophthalmol. 1979;20:141–147. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duvall J., Tso M. O. Cellular mechanisms of resolution of drusen after laser coagulation. An experimental study. Arch Ophthalmol. 1985 May;103(5):694–703. doi: 10.1001/archopht.1985.01050050086024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Figueroa M. S., Regueras A., Bertrand J. Laser photocoagulation to treat macular soft drusen in age-related macular degeneration. Retina. 1994;14(5):391–396. doi: 10.1097/00006982-199414050-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fine S. L., Patz A., Orth D. H., Klein M. L., Finkelstein D., Yassur Y. Subretinal neovascularization developing after prophylactic argon laser photocoagulation of atrophic macular scars. Am J Ophthalmol. 1976 Sep;82(3):352–357. doi: 10.1016/0002-9394(76)90483-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Folkman J. Angiogenesis: initiation and control. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 1982;401:212–227. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1982.tb25720.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- François J., De Laey J. J., Cambie E., Hanssens M., Victoria-Troncoso V. Neovascularization after argon laser photocoagulation of macular lesions. Am J Ophthalmol. 1975 Feb;79(2):206–210. doi: 10.1016/0002-9394(75)90073-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frennesson I. C., Nilsson S. E. Effects of argon (green) laser treatment of soft drusen in early age-related maculopathy: a 6 month prospective study. Br J Ophthalmol. 1995 Oct;79(10):905–909. doi: 10.1136/bjo.79.10.905. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galinos S. O., Asdourian G. K., Woolf M. B., Goldberg M. F., Busse B. J. Choroido-vitreal neovascularization after argon laser photocoagulation. Arch Ophthalmol. 1975 Jul;93(7):524–530. doi: 10.1001/archopht.1975.01010020540012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garron L. K. The Ultrastructure of the Retinal Pigment Epithelium with Observations on the Choriocapillaris and Bruch's Membrane. Trans Am Ophthalmol Soc. 1963;61:545–588. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gass J. D. Drusen and disciform macular detachment and degeneration. Arch Ophthalmol. 1973 Sep;90(3):206–217. doi: 10.1001/archopht.1973.01000050208006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glaser B. M. Extracellular modulating factors and the control of intraocular neovascularization. An overview. Arch Ophthalmol. 1988 May;106(5):603–607. doi: 10.1001/archopht.1988.01060130657020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grierson I., Day J., Unger W. G., Ahmed A. Phagocytosis of latex microspheres by bovine meshwork cells in culture. Graefes Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol. 1986;224(6):536–544. doi: 10.1007/BF02154742. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guymer R. H., Gross-Jendroska M., Owens S. L., Bird A. C., Fitzke F. W. Laser treatment in subjects with high-risk clinical features of age-related macular degeneration. Posterior pole appearance and retinal function. Arch Ophthalmol. 1997 May;115(5):595–603. doi: 10.1001/archopht.1997.01100150597004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haut J., Renard Y., Kraiem S., Bensoussan C., Moulin F. Traitement prophylactique par laser de la DMLA de l'oeil adelphe après DMLA du premier oeil. J Fr Ophtalmol. 1991;14(8-9):473–476. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heriot W. J., Henkind P., Bellhorn R. W., Burns M. S. Choroidal neovascularization can digest Bruch's membrane. A prior break is not essential. Ophthalmology. 1984 Dec;91(12):1603–1608. doi: 10.1016/s0161-6420(84)34112-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kalebic T., Garbisa S., Glaser B., Liotta L. A. Basement membrane collagen: degradation by migrating endothelial cells. Science. 1983 Jul 15;221(4607):281–283. doi: 10.1126/science.6190230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Killingsworth M. C. Angiogenesis in early choroidal neovascularization secondary to age-related macular degeneration. Graefes Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol. 1995 Jun;233(6):313–323. doi: 10.1007/BF00200479. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Korte G. E., Chase J. Additional evidence for remodelling of normal choriocapillaris. Exp Eye Res. 1989 Aug;49(2):299–303. doi: 10.1016/0014-4835(89)90100-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leeson T. S., Leeson C. R. Choriocapillaris and lamina elastica (vitrea) of the rat eye. Br J Ophthalmol. 1967 Sep;51(9):599–616. doi: 10.1136/bjo.51.9.599. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matsusaka T. Undescribed endothelial processes of the choriocapillaris extending to the retinal pigment epithelium of the chick. Br J Ophthalmol. 1968 Dec;52(12):887–892. doi: 10.1136/bjo.52.12.887. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moore D. J., Hussain A. A., Marshall J. Age-related variation in the hydraulic conductivity of Bruch's membrane. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 1995 Jun;36(7):1290–1297. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Owens S. L., Guymer R. H., Gross-Jendroska M., Bird A. C. Fluorescein angiographic abnormalities after prophylactic macular photocoagulation for high-risk age-related maculopathy. Am J Ophthalmol. 1999 Jun;127(6):681–687. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9394(99)00043-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pollack A., Heriot W. J., Fraco, Fracs, Henkind P. Cellular processes causing defects in Bruch's membrane following krypton laser photocoagulation. Ophthalmology. 1986 Aug;93(8):1113–1119. doi: 10.1016/s0161-6420(86)33614-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pollack A., Korte G. E., Weitzner A. L., Henkind P. Ultrastructure of Bruch's membrane after krypton laser photocoagulation. I. Breakdown of Bruch's membrane. Arch Ophthalmol. 1986 Sep;104(9):1372–1376. doi: 10.1001/archopht.1986.01050210126039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ryan S. J. The development of an experimental model of subretinal neovascularization in disciform macular degeneration. Trans Am Ophthalmol Soc. 1979;77:707–745. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sigelman J. Foveal drusen resorption one year after perifoveal laser photocoagulation. Ophthalmology. 1991 Sep;98(9):1379–1383. doi: 10.1016/s0161-6420(91)32122-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taugner R., Kirchheim H., Forssmann W. G. Myoendothelial contacts in glomerular arterioles and in renal interlobular arteries of rat, mouse and Tupaia belangeri. Cell Tissue Res. 1984;235(2):319–325. doi: 10.1007/BF00217856. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wetzig P. C. Photocoagulation of drusen-related macular degeneration: a long-term outcome. Trans Am Ophthalmol Soc. 1994;92:299–306. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wetzig P. C. Treatment of drusen-related aging macular degeneration by photocoagulation. Trans Am Ophthalmol Soc. 1988;86:276–290. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamamoto T., Fukuda S., Obata H., Yamashita H. Electron microscopic observation of pseudopodia from choriocapillary endothelium. Jpn J Ophthalmol. 1994;38(2):129–138. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamamoto T., Yamashita H. Pseudopodia of capillary endothelium in ocular tissues. Jpn J Ophthalmol. 1990;34(2):181–187. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamamoto T., Yamashita H. Pseudopodia of choriocapillary endothelium. Jpn J Ophthalmol. 1989;33(3):327–336. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]