Abstract

BACKGROUND/AIM—It is widely accepted that hypercapnia results in increased retinal, choroidal, and retrobulbar blood flow. Reports of a visual response to hypercapnia appear mixed, with normal subjects exhibiting reduced temporal contrast sensitivity in some studies, while glaucoma patients demonstrate mid-peripheral visual field improvements in others. This suggests that under hypercapnic conditions a balance exists between the beneficial effects of improved ocular blood flow and some other factor such as induced metabolic stress; the outcome may be influenced by the disease process. The aim of this study was to evaluate the contrast sensitivity response of untreated glaucoma patients and normal subjects during mild hypercapnia. METHODS—10 previously untreated glaucoma patients and 10 control subjects were evaluated for contrast sensitivity and intraocular pressure while breathing room air and then again during mild hypercapnia. RESULTS—During room air breathing, compared with normal subjects, glaucoma patients had higher IOP (p = 0.0003) and lower contrast sensitivity at 3 cycles/degree (cpd) (p = 0.001). Mild hypercapnia caused a significant fall in contrast sensitivity at 6, 12, and 18 cpd (p < 0.05), only in the glaucoma group. CONCLUSION—Glaucoma patients with early disease exhibit central vision deficits as shown by contrast sensitivity testing at 3 cpd. Hypercapnia induces further contrast loss through a range of spatial frequencies (6-18 cpd) which may be predictive of further neuronal damage due to glaucoma.

Full Text

The Full Text of this article is available as a PDF (136.2 KB).

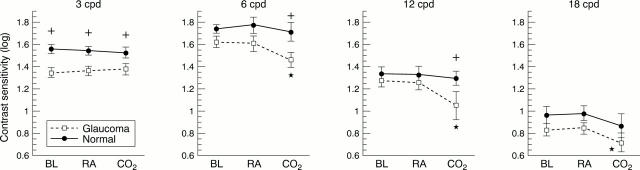

Figure 1 .

Contrast sensitivity outcomes measured at 3, 6, 12, and 18 cycles per degree (cpd) for glaucoma patients and normal subjects. Measurements were taken at baseline (BL), in room air through a breathing mask (RA), and while breathing carbon dioxide (CO2 ). Significant differences between groups are noted by the plus symbol, and differences due to conditions are noted by an asterisk.

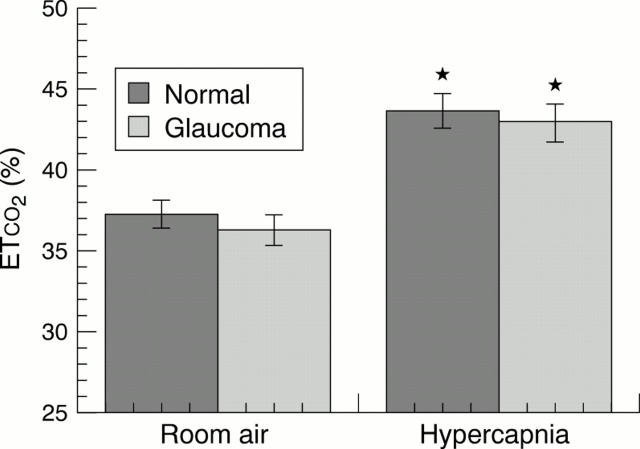

Figure 2 .

Histogram showing end tidal carbon dioxide levels (ETCO2 )in room air and in hypercapnia for normal subjects and glaucoma patients. Significant differences from baseline are indicated by an asterisk.

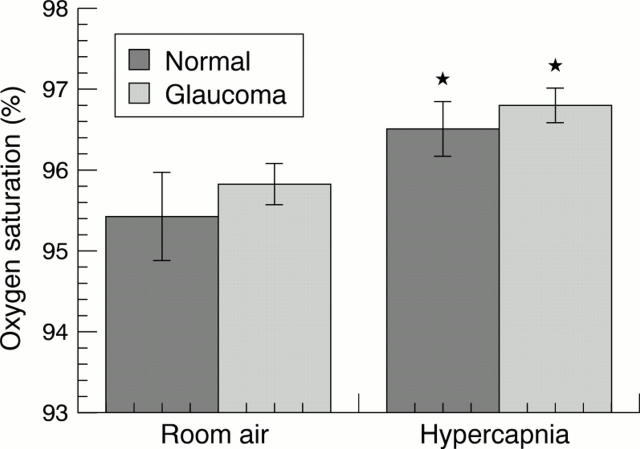

Figure 3 .

Oxygen saturation levels measured by pulse oximetry in room air and hypercapnia for normal subjects and glaucoma patients. Significant differences from baseline are indicated by an asterisk.

Selected References

These references are in PubMed. This may not be the complete list of references from this article.

- Andersen M. V. Changes in the vitreous body pH of pigs after retinal xenon photocoagulation. Acta Ophthalmol (Copenh) 1991 Apr;69(2):193–199. doi: 10.1111/j.1755-3768.1991.tb02710.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arend O., Remky A., Evans D., Stüber R., Harris A. Contrast sensitivity loss is coupled with capillary dropout in patients with diabetes. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 1997 Aug;38(9):1819–1824. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bee J. A., Roche S. M. Reducing intraocular pressure by intubation elicits precocious development and innervation of the embryonic chick cornea. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 1992 Nov;33(12):3469–3478. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deutsch T. A., Read J. S., Ernest J. T., Goldstick T. K. Effects of oxygen and carbon dioxide on the retinal vasculature in humans. Arch Ophthalmol. 1983 Aug;101(8):1278–1280. doi: 10.1001/archopht.1983.01040020280023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evans D. W., Harris A., Cantor L. B. Primary open-angle glaucoma patients characterized by ocular vasospasm demonstrate a different ocular vascular response to timolol versus betaxolol. J Ocul Pharmacol Ther. 1999 Dec;15(6):479–487. doi: 10.1089/jop.1999.15.479. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fallon T. J., Maxwell D., Kohner E. M. Retinal vascular autoregulation in conditions of hyperoxia and hypoxia using the blue field entoptic phenomenon. Ophthalmology. 1985 May;92(5):701–705. doi: 10.1016/s0161-6420(85)33978-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fechtner R. D., Weinreb R. N. Mechanisms of optic nerve damage in primary open angle glaucoma. Surv Ophthalmol. 1994 Jul-Aug;39(1):23–42. doi: 10.1016/s0039-6257(05)80042-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flammer J., Haefliger I. O., Orgül S., Resink T. Vascular dysregulation: a principal risk factor for glaucomatous damage? J Glaucoma. 1999 Jun;8(3):212–219. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Friedman E., Chandra S. R. Choroidal blood flow. 3. Effects of oxygen and carbon dioxide. Arch Ophthalmol. 1972 Jan;87(1):70–71. doi: 10.1001/archopht.1972.01000020072015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grunwald J. E., Riva C. E., Stone R. A., Keates E. U., Petrig B. L. Retinal autoregulation in open-angle glaucoma. Ophthalmology. 1984 Dec;91(12):1690–1694. doi: 10.1016/s0161-6420(84)34091-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haefliger I. O., Lietz A., Griesser S. M., Ulrich A., Schötzau A., Hendrickson P., Flammer J. Modulation of Heidelberg Retinal Flowmeter parameter flow at the papilla of healthy subjects: effect of carbogen, oxygen, high intraocular pressure, and beta-blockers. Surv Ophthalmol. 1999 Jun;43 (Suppl 1):S59–S65. doi: 10.1016/s0039-6257(99)00025-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harris A., Anderson D. R., Pillunat L., Joos K., Knighton R. W., Kagemann L., Martin B. J. Laser Doppler flowmetry measurement of changes in human optic nerve head blood flow in response to blood gas perturbations. J Glaucoma. 1996 Aug;5(4):258–265. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harris A., Arend O., Danis R. P., Evans D., Wolf S., Martin B. J. Hyperoxia improves contrast sensitivity in early diabetic retinopathy. Br J Ophthalmol. 1996 Mar;80(3):209–213. doi: 10.1136/bjo.80.3.209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harris A., Arend O., Kagemann L., Garrett M., Chung H. S., Martin B. Dorzolamide, visual function and ocular hemodynamics in normal-tension glaucoma. J Ocul Pharmacol Ther. 1999 Jun;15(3):189–197. doi: 10.1089/jop.1999.15.189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harris A., Evans D. W., Cantor L. B., Martin B. Hemodynamic and visual function effects of oral nifedipine in patients with normal-tension glaucoma. Am J Ophthalmol. 1997 Sep;124(3):296–302. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9394(14)70821-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harris A., Sergott R. C., Spaeth G. L., Katz J. L., Shoemaker J. A., Martin B. J. Color Doppler analysis of ocular vessel blood velocity in normal-tension glaucoma. Am J Ophthalmol. 1994 Nov 15;118(5):642–649. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9394(14)76579-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harris A., Sergott R. C., Spaeth G. L., Katz J. L., Shoemaker J. A., Martin B. J. Color Doppler analysis of ocular vessel blood velocity in normal-tension glaucoma. Am J Ophthalmol. 1994 Nov 15;118(5):642–649. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9394(14)76579-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harris A., Tippke S., Sievers C., Picht G., Lieb W., Martin B. Acetazolamide and CO2: acute effects on cerebral and retrobulbar hemodynamics. J Glaucoma. 1996 Feb;5(1):39–45. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hiroi K., Yamamoto F., Honda Y. Analysis of electroretinogram during systemic hypercapnia with intraretinal K(+)-microelectrodes in cats. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 1994 Oct;35(11):3957–3961. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kety S. S., Schmidt C. F. THE EFFECTS OF ALTERED ARTERIAL TENSIONS OF CARBON DIOXIDE AND OXYGEN ON CEREBRAL BLOOD FLOW AND CEREBRAL OXYGEN CONSUMPTION OF NORMAL YOUNG MEN. J Clin Invest. 1948 Jul;27(4):484–492. doi: 10.1172/JCI101995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuboyama T., Hori A., Sato T., Mikami T., Yamaki T., Ueda S. Changes in cerebral blood flow velocity in healthy young men during overnight sleep and while awake. Electroencephalogr Clin Neurophysiol. 1997 Feb;102(2):125–131. doi: 10.1016/s0921-884x(96)95054-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lietz A., Hendrickson P., Flammer J., Orgül S., Haefliger I. O. Effect of carbogen, oxygen and intraocular pressure on Heidelberg retina flowmeter parameter 'flow' measured at the papilla. Ophthalmologica. 1998;212(3):149–152. doi: 10.1159/000027265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Michelson G., Langhans M. J., Groh M. J. Perfusion of the juxtapapillary retina and the neuroretinal rim area in primary open angle glaucoma. J Glaucoma. 1996 Apr;5(2):91–98. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Milley J. R., Rosenberg A. A., Jones M. D., Jr Retinal and choroidal blood flows in hypoxic and hypercarbic newborn lambs. Pediatr Res. 1984 May;18(5):410–414. doi: 10.1203/00006450-198405000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nicolela M. T., Drance S. M., Rankin S. J., Buckley A. R., Walman B. E. Color Doppler imaging in patients with asymmetric glaucoma and unilateral visual field loss. Am J Ophthalmol. 1996 May;121(5):502–510. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9394(14)75424-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pillunat L. E., Anderson D. R., Knighton R. W., Joos K. M., Feuer W. J. Autoregulation of human optic nerve head circulation in response to increased intraocular pressure. Exp Eye Res. 1997 May;64(5):737–744. doi: 10.1006/exer.1996.0263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pillunat L. E., Lang G. K., Harris A. The visual response to increased ocular blood flow in normal pressure glaucoma. Surv Ophthalmol. 1994 May;38 (Suppl):S139–S148. doi: 10.1016/0039-6257(94)90058-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pomerance G. N., Evans D. W. Test-retest reliability of the CSV-1000 contrast test and its relationship to glaucoma therapy. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 1994 Aug;35(9):3357–3361. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ringelstein E. B., Van Eyck S., Mertens I. Evaluation of cerebral vasomotor reactivity by various vasodilating stimuli: comparison of CO2 to acetazolamide. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 1992 Jan;12(1):162–168. doi: 10.1038/jcbfm.1992.20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Riva C. E., Grunwald J. E., Petrig B. L. Autoregulation of human retinal blood flow. An investigation with laser Doppler velocimetry. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 1986 Dec;27(12):1706–1712. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Riva C. E., Grunwald J. E., Sinclair S. H. Laser Doppler Velocimetry study of the effect of pure oxygen breathing on retinal blood flow. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 1983 Jan;24(1):47–51. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Samuel J. R., Beaugié A. Effect of carbon dioxide on the intraocular pressure in man during general anaesthesia. Br J Ophthalmol. 1974 Jan;58(1):62–67. doi: 10.1136/bjo.58.1.62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sonnsjö B., Krakau C. E. Arguments for a vascular glaucoma etiology. Acta Ophthalmol (Copenh) 1993 Aug;71(4):433–444. doi: 10.1111/j.1755-3768.1993.tb04615.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sponsel W. E., DePaul K. L., Kaufman P. L. Correlation of visual function and retinal leukocyte velocity in glaucoma. Am J Ophthalmol. 1990 Jan 15;109(1):49–54. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9394(14)75578-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sponsel W. E., Harrison J., Elliott W. R., Trigo Y., Kavanagh J., Harris A. Dorzolamide hydrochloride and visual function in normal eyes. Am J Ophthalmol. 1997 Jun;123(6):759–766. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9394(14)71124-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Buskirk E. M., Cioffi G. A. Predicted outcome from hypotensive therapy for glaucomatous optic neuropathy. Am J Ophthalmol. 1993 Nov 15;116(5):636–640. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9394(14)73208-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]