Abstract

The neuropeptides vasoactive intestinal peptide (VIP) and pituitary adenylate cyclase-activating polypeptide (PACAP) belong to a superfamily of structurally related peptide hormones that includes glucagon, glucagon-like peptides, secretin, and growth hormone-releasing hormone. Microinjection of VIP or PACAP into the rodent suprachiasmatic nucleus (SCN) phase shifts the circadian pacemaker and VIP antagonists, and antisense oligodeoxynucleotides have been shown to disrupt circadian function. VIP and PACAP have equal potency as agonists of the VPAC2 receptor (VPAC2R), which is expressed abundantly in the SCN, in a circadian manner. To determine whether manipulating the level of expression of the VPAC2R can influence the control of the circadian clock, we have created transgenic mice overexpressing the human VPAC2R gene from a yeast artificial chromosome (YAC) construct. The YAC was modified by a strategy using homologous recombination to introduce (i) the HA epitope tag sequence (from influenza virus hemagglutinin) at the carboxyl terminus of the VPAC2R protein, (ii) the lacZ reporter gene, and (iii) a conditional centromere, enabling YAC DNA to be amplified in culture in the presence of galactose. High levels of lacZ expression were detected in the SCN, habenula, pancreas, and testis of the transgenic mice, with lower levels in the olfactory bulb and various hypothalamic areas. Transgenic mice resynchronized more quickly than wild-type controls to an advance of 8 h in the light-dark (LD) cycle and exhibited a significantly shorter circadian period in constant darkness (DD). These data suggest that the VPAC2R can influence the rhythmicity and photic entrainment of the circadian clock.

Evidence is accumulating to suggest that the neuropeptides vasoactive intestinal peptide (VIP) and pituitary adenylate cyclase-activating polypeptide (PACAP) may play important roles in the control of the circadian clock in the suprachiasmatic nucleus (SCN). VIP is synthesized in cells of the retinorecipient region of the rodent SCN (1, 2), at least some of which may have a direct retinal input (3). These cells form synapses with vasopressin-containing cells in the dorsomedial SCN as well as contacts with other VIP cells (4). There is diurnal variation of VIP immunoreactivity (5) and prepro VIP mRNA (6, 7) in the SCN. Exogenous VIP can mimic the phase-advancing and -delaying effects of light pulses (8, 9). VIP antagonists (10) and VIP antisense oligodeoxynucleotides (11) have been shown to disrupt circadian function. Elevated SCN levels of VIP mRNA have been found in two mutant rodent strains [the tau mutant hamster (12) and the spontaneously hypertensive (SHR) rat (13)] that exhibit a significantly shorter free-running period in constant darkness (DD), consistent with an involvement of VIP in establishing the free-running period of the circadian clock.

In the SCN, PACAP originates almost exclusively from a subpopulation of glutamate-containing retinal ganglion cells (14, 15) that terminate in the retinorecipient region of the SCN. The PACAP content of these terminals is low in the day and high at night (16). Administration of PACAP to the SCN both in vivo (17) and in vitro (15, 17) resets the circadian clock in a manner similar to light.

VIP and PACAP exert their actions through a family of three G protein-coupled receptors (18), two of which (VPAC2 receptors and PAC1 receptors) are expressed in the SCN. The PAC1 receptor is selective for PACAP, whereas the VPAC2R has equal affinity for both VIP and PACAP. Biphasic variation of VPAC2R expression was found in the SCN of animals kept in a 12:12 h light-dark (LD) cycle, with peaks at mid-day and in the latter part of the night (19). In animals transferred to DD, the two peaks of VPAC2R mRNA expression occurred in the latter part of the subjective day and in the latter part of the subjective night.

To establish the physiological functions of the VPAC2R and the mechanisms, by which expression of the receptor is regulated, we have adopted a transgenic approach. A yeast artificial chromosome (YAC) clone containing the human VPAC2R gene (≈117 kb), with extensive 5′ and 3′ flanking sequences, was modified to introduce the influenza virus hemagglutinin (HA) epitope tag at the C terminus of the VPAC2R protein and a lacZ reporter gene, downstream of a viral internal ribosomal entry site (IRES) into the 3′ untranslated region of the gene. In transgenic mice containing this YAC construct, lacZ was expressed in a tissue-specific pattern, closely resembling that of the endogenous rodent VPAC2R, with the highest levels of expression in the SCN. In comparison to wild-type controls, transgenic mice resynchronized more quickly to an 8-h advance in the LD cycle and exhibited a significantly shorter circadian period in DD.

Materials and Methods

YAC Amplification Vector pYAM4 and Insertion Vector pYIV3.

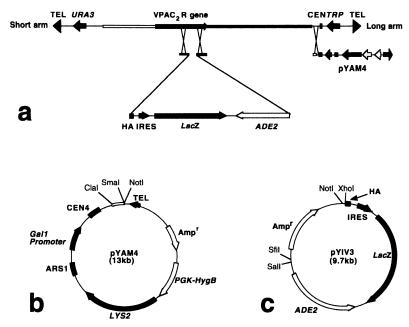

The two-step YAC manipulation system used for production of transgenic mice is shown in Fig. 1a. pYAM4 is a derivative of pBluescript SK− that contains a 572-bp SmaI-ClaI fragment from pYAC4, linked to a conditional centromere (CEN4) that can be inactivated by induced transcription from an adjacent GAL1 promoter, and yeast telomere sequences from pYAC4. pYAM4 also contains the yeast LYS2 gene and the Escherichia coli hygromycin B resistance gene driven by the mouse Pgk1 promoter (Fig. 1b). pYIV3 is a derivative of pGEM-11Zf that encodes (i) the amino acid sequence (EYPYDVPDYASL) of the HA epitope tag; (ii) the lacZ reporter gene, flanked by a viral IRES and polyadenylation sequences from SV40; and (iii) the yeast ADE2 gene (Fig. 1c). The HA-IRES-lacZ-ADE2 cassette is flanked by unique restriction sites to facilitate cloning of genomic sequences corresponding to the desired site of homologous recombination in the target YAC.

Figure 1.

Two-step genetic manipulation of YAC DNA by homologous recombination (a) using YAC amplification vector pYAM4 (b) and YAC insertion vector pYIV3 (c). A YAC contains an insert of genomic DNA between short and long vector arms. In step 1, genomic sequences flanking the desired site of insertion in the target gene are cloned either side of the HA-IRES-lacZ-ADE2 cassette in pYIV3. Integration of the HA-IRES-lacZ-ADE2 cassette into the YAC can be verified by hybridization with an ADE2 probe. In step 2, pYAM4 is used to replace the long vector arm so that the YAC DNA can be amplified when grown in medium containing galactose.

Modification of YAC Clone HSC7E526 and Production of Transgenic Mice.

A 1.6-kb NotI-BamHI fragment of cosmid clone cos79g3 (20) was modified by PCR-based mutagenesis to introduce an XhoI restriction site at the stop codon, and the 1.3-kb NotI-XhoI fragment extending upstream from the stop codon was cloned into the NotI-XhoI sites of pYIV3, generating pVPAC2HAlacZA. A 1.6-kb XhoI-KpnI fragment of the VPAC2R gene extending downstream from the stop codon was obtained by PCR of cos79g3 by using primers 5′-CAAACGGAGACCTCGGTCCTCGAGCCCCAC-3′ and 5′-CGGGTACCAAAATGGTGGGTTGTTCTGTAA-3′ and subcloned into the XhoI-KpnI sites of pBluescript SK−, generating p3′VPAC2R. Finally, a 7.5-kb NotI-SalI fragment of pVPAC2HAlacZA was ligated into NotI-XhoI digested p3′VPAC2R, resulting in a construct, placZVPAC2R.

placZVPAC2R was linearized with NotI and transformed into yeast clone HSC7E526 (Gift from S. W. Scherer, Hospital for Sick Children, Toronto, Canada). A recombinant clone (HSC7E526/V12), which incorporated the HA-lacZ-ADE2 cassette was transformed with NotI-linearized pYAM4. Ura+ Ade+ Lys+ recombinants were streaked on plates lacking tryptophan. Lys+ Trp− clones were cultured in medium with 2% galactose. YAC DNA was isolated, analyzed, and purified by pulsed field gel electrophoresis as described by Schedl et al. (21). Transgenic lines were generated and maintained on a mixed genetic background of CBA × C57BL/6J.

Histochemical Detection of β-Galactosidase Activity.

Mice were killed with a lethal dose of sodium pentobarbitone, briefly perfused through the heart with 0.9% NaCl to remove blood, and fixed by slow perfusion with ≈50 ml ice-cold fixative (4% paraformaldehyde in PBS, pH7.4). The brains and internal organs were dissected rapidly and postfixed in the same fixative for 1 h at 4°C. After transfer to 30% sucrose in PBS overnight at 4°C, 40-μm coronal sections of the brain were produced on a freezing microtome, washed in PBS, transferred into X-Gal (5-bromo-4-chloro-3-indolyl-β-d-galactoside) staining solution (1 mg/ml X-Gal/5 mM K4Fe(CN)6/5 mM K3Fe(CN)6/2 mM MgCl2/0.01% sodium deoxycholate/0.02% Nonidet P-40 in PBS) and incubated with gentle shaking at 30°C overnight. After staining, sections were washed in PBS and mounted onto slides before examination and photography. Alternatively, intact peripheral organs and ≈2-mm coronal slices of the brain were stained overnight in X-Gal staining solution at 30°C.

Immunocytochemistry for β-Galactosidase and for the HA Epitope Tag.

Animals were killed as above and perfused transcardially with 2% paraformaldehyde and 0.25% glutaraldehyde in PBS. Brains were postfixed overnight in 2% paraformaldehyde in PBS, then transferred into PBS. Fifty-micrometer-thick vibratome sections were collected in multiwell plates and treated with 1% NaBH4 (30 min) and 0.5% Triton X-100 (20 min). Endogenous peroxidase activity was blocked with 0.1% H2O2. Nonspecific binding of secondary antiserum to the tissue was minimized by preincubation with 2% normal donkey serum for 30 min. Sections were incubated in primary antibody [rabbit anti β-galactosidase, 1:20,000 (5 Prime→3 Prime) or rat monoclonal anti-HA clone 3F10, 0.1 μg/ml (Boehringer Mannheim)] for 48 h at 4°C. Sections were then incubated for 60 min in secondary antibody [biotinylated donkey anti-rabbit IgG or biotinylated goat anti-rat IgG (Jackson ImmunoResearch), diluted at 1:1000] and for 60 min with an avidin-biotin-peroxidase reagent (ABC Elite; Vector Laboratories; 1:1000 dilution). Immunoreactivity was revealed with a nickel-enhanced diaminobenzidine (NiDAB) reaction. Sections were mounted from Elvanol, dehydrated, and coverslipped with DEPEX (BDH Laboratory Supplies). To confirm the specificity of staining, some sections were incubated with primary antiserum that had been preincubated with an excess (5 μg/ml) of the appropriate antigen (E. coli β-galactosidase from Sigma or HA peptide from Boehringer Mannheim).

Behavioral Analysis.

General.

The light-proof animal room, serviced through a light lock, was maintained at 21 ± 0.5°C. Adult male mice (14 transgenic and 8 nontransgenic littermates) were individually housed in polycarbonate cages (Eurostandard Type 2L, 365 × 207 × 140 mm), each equipped with a running wheel (240 × 80 mm from Tecniplast, Kettering, U.K.). Deep litter bedding (40-mm depth) was provided in each cage; food and water were available ad libitum. Animals were inspected daily, in accordance with United Kingdom legislation, according to a randomized schedule.

Running-wheel activity was monitored by means of reed relays activated by four miniature magnets positioned 90° apart on each wheel. One count was equivalent to 189 mm traveled horizontally. The detectors were monitored continuously by Dataquest ART system (DSI, Saint Paul, MN), which collated activity counts into 3-min time bins across the duration of the experiment.

Experimental design.

The running-wheel activity of mice habituated to a 12:12-h LD cycle (dark from 19:00 to 07:00) was recorded. “Darkness” consisted of constant dim red light providing <7 lux at cage level. The emission spectrum of this light source was between 600 and 700 nm, a range within the red part of the spectrum and outside the spectral sensitivity curve for the circadian phase-shifting response (22). After an initial 6 days of monitoring, the LD cycle was advanced by 8 h (dark from 11:00 to 23:00) via a shortened light period of 4 h. This pattern was maintained for 10 days before reverting to the original lighting regime (dark from 19:00 to 07:00) via an 8-h delay in the onset of darkness. This lighting regime was maintained for 13 days, during which the bedding was renewed on the ninth day. Subsequently, animals were kept in DD for 33 days.

Data analysis.

clocklab software (Actimetrics, Evanston, IL) was used to derive from the activity record of each animal: (i) the number of days to entrain to a new LD cycle after the short and long day shifts; (ii) the overall activity levels, defined as the mean daily wheel-running counts during the last 10 days of the LD phase before entering DD; and (iii) the circadian period of the free-running rhythm under DD conditions (tau), which was calculated for each animal from the slope of a regression line fitted to the activity onsets, for days 2 to 12 of the DD period.

All data were analyzed by using one-way ANOVA after confirmation of normality and equality of variance (sigmastat version 2.03, SPSS, Birmingham, U.K.). Where appropriate, significant results were interpreted after post hoc analysis with Tukey's test.

Results

Modification of YAC Clone HSC7E526 By using pYIV3 and pYAM4.

We have shown previously that the YAC clone HSC7E526 contains the VPAC2R gene flanked by >100 kb of 5′ and 3′ flanking sequence (23). After transformation of HSC7E526 with the pYIV3-based placZVPAC2R vector, 12 Ura+ Ade+ Trp+ clones were obtained. Pulsed-field gel electrophoresis followed by Southern blotting with an ADE2 probe showed that homologous recombination had taken place at the desired site in 11 of the 12 transformants. One Ura+ Ade+ Trp+ YAC subclone (HSC7E526/V12) was subsequently transformed with NotI-linearized pYAM4, and Ura+ Ade+ Lys+ recombinants were obtained. Of 107 Ura+ Ade+ Lys+ clones, 8 could not grow on medium lacking tryptophan, indicating the efficient replacement of the long YAC vector arm by pYAM4.

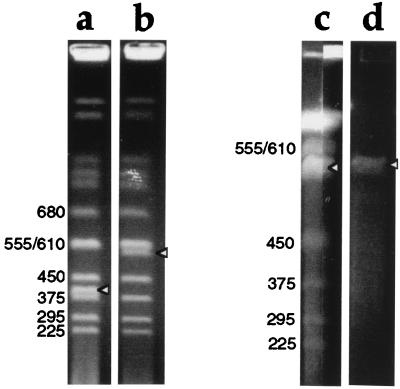

The Ura+ Ade+ Lys+ Trp− recombinants were cultured in medium with 2% galactose but lacking uracil, adenine, and lysine. Amplification of YAC DNA by pYAM4 was assessed by comparing the intensity of ethidium bromide staining of YAC DNA to that of yeast endogenous chromosomes of similar size (Fig. 2). The yield of the amplified YAC DNA (Fig. 2c, arrowhead) was approximately 3–4 times that obtained with the unmodified YAC HSC7E526 (Fig. 2b, arrowhead).

Figure 2.

Ethidium bromide staining of pulsed-field gels showing YAC DNA amplification and purification. Sizes in kilobases of yeast chromosomes are indicated, and bands corresponding to YAC DNA are indicated with arrowheads. (a and b) YAC clones before amplification, run on a 0.9% agarose gel in 0.5× TBE, at 6V/cm, 4°C for 24 h with 60 s switch time. (a) DNA from yeast containing a 400-kb YAC; (b) DNA from the 550-kb YAC HSC7E526. The intensity of ethidium bromide staining of the 550 kb YAC (b) is approximately half that of the band above, which contains two yeast chromosomes (555 and 610 kb) unresolved from one another. (c) DNA from pYIV3- and pYAM4-modified HSC7E526, run on a preparative scale in a 1% agarose gel in 0.25× TAE, at 6V/cm, 4°C for 32 h with 30 and 55 s switch time. Thirty-nine agarose plugs (0.5 cm × 0.15 cm × 1 cm) containing YAC DNA were loaded into a sample well 19.5 cm wide and sealed with agarose. After electrophoresis, the central 17 cm of the gel was kept for the purification of YAC DNA, and the remainder of the gel was stained with ethidium bromide and photographed. The two stained portions of the gel, each containing about 0.5 cm of the preparative lane, are shown. The intensity of staining of the YAC DNA is 1.5 to ≈2× that of the band above. (d) Gel-purified YAC DNA before microinjection into fertilized eggs.

Generation of Transgenic Mice Harboring Intact Modified YAC DNA.

After gel purification (Fig. 2d), YAC DNA was microinjected into the pronuclei of 364 fertilized eggs from (CBA × C57BL/6J) F1 female mice. Seven (7.6%) transgenic mice were identified by PCR from the 92 living offspring, and 6 of them contained the intact YAC DNA, as indicated by the presence of five STS markers (sWSS2567, sWSS1117, sWSS225, sWSS2552, and D7S68), together with the long and short YAC vector arms. Germ-line transmission was obtained from all transgenic founders. These data indicate that the amplification of YAC DNA by pYAM4 resulted in a high proportion of transgenic offspring containing the intact YAC construct.

Expression of the lacZ Reporter Gene and the Human VPAC2R Gene in YAC Transgenic Mice.

Histochemical staining of the lacZ reporter gene showed that the strongest expression within the brain was in the SCN (Fig. 3 A and E). lacZ staining was also detected in the olfactory bulb (Fig. 3B) and accessory olfactory bulb (not shown), in the lateral septum (Fig. 3C), medial preoptic area (Fig. 3D), and habenula (Fig. 3A), as well as in a small number of cells in the supraoptic nucleus (Fig. 3 D and E). Additionally, expression was apparent in the walls of the cerebral blood vessels (Fig. 3 F and H), in the ependymal cell layers of the III and IV ventricles and aqueduct (Fig. 3 F and G), and in circumventricular organs, including the subcommissural organ and the subfornical organ (not shown). No staining in brain sections from nontransgenic mice was observed under the same conditions. In the peripheral organs, lacZ was expressed at high levels in the pancreas (Fig. 3I) and testis (not shown) and at lower levels in the spleen (Fig. 3J) of transgenic, but not wild-type, mice.

Figure 3.

Histochemical (A–J) and immunocytochemical (K–O) demonstration of transgene expression in brain and peripheral tissues of A108.2 transgenic mice. (A) Complete coronal slice of brain showing lacZ expression in the SCN and in the medial habenula (MHb). Cells positive for lacZ (B) in the glomerular and internal granular layers of the olfactory bulb, (C) in the lateral septum, (D) in a small number of cells in the medial preoptic area (MPO) and in the supraoptic nuclei (SON), (E) in the SCN, (F) in the ependymal cell layer of the rostral portion of the third ventricle (III) and in the walls of numerous blood vessels (arrowed), (G) in the ependymal cell layer of the fourth ventricle (IV), (H) in a slice of the brain that includes both the midbrain and the caudal portion of the forebrain, showing strong expression of lacZ in the walls of the major cerebral blood vessels, (I) in the pancreas of a transgenic (tg), but not of a wild-type (wt) mouse, and (J) in the spleen of a transgenic (tg), but not of a wild-type (wt) mouse. β-galactosidase-like immunoreactivity (K) in cells and processes in the SCN and (L) in the medial habenular nucleus. HA-like immunoreactivity (M and N) in the medial habenular nucleus; the membrane-associated immunoreactivity for this antigen is clearly seen in some cases (arrowed). Labeling was absent (O) when the antiserum had been preincubated with excess HA peptide. lv, lateral ventricle; Aq, aqueduct; LSi, intermediate portion of the lateral septal nucleus; LSv, ventral portion of the lateral septal nucleus; ox, optic chiasm.

The pattern of immunocytochemical staining for β-galactosidase- and HA-like immunoreactivity (Fig. 3 K–N) was similar to that shown by histochemical staining of lacZ. The β-galactosidase-immunoreactivity was present within cell bodies and proximal processes in either a diffuse or punctate form (Fig. 3 K and L). The staining obtained with the HA antiserum was confined to the margin of the cells, consistent with the presence of the VPAC2 receptor protein in the cell membrane (Fig. 3 M and N). Preincubation of antibodies with the appropriate antigen abolished the immunohistochemical staining of both HA (Fig. 3O) and β-galactosidase (not shown). These data demonstrate that both the epitope-tagged VPAC2R protein and the lacZ reporter gene are coexpressed in these transgenic mice.

Behavioral Analysis.

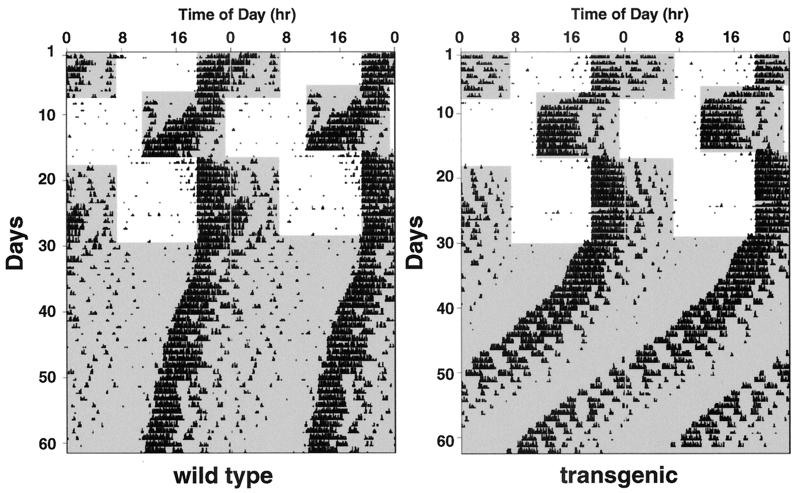

Representative double plot actograms for transgenic and control mice are shown in Fig. 4. Both groups of animals entrained to the initial LD cycle, exhibited vigorous wheel running, and showed no significant difference in overall activity, suggesting that the overexpression of the VPAC2R does not grossly affect normal motor function (Table 1). Transgenic animals required significantly less time (on average 1.5 days) to re-entrain to an 8-h advance in the LD cycle than wild-type controls (Table 1). Transgenic animals also appeared to re-entrain more quickly than the controls to the subsequent phase delay of 8 h (2.7 vs. 3.4 days), but this difference failed to reach significance. Under DD conditions, transgenic mice showed a free running rhythm significantly shorter than the control mice (Table 1).

Figure 4.

Representative profiles of locomotor activity in VPAC2R transgenic and wild-type mice. Records are double-plotted so that 48 h are shown for each horizontal trace and consecutive days are aligned vertically and duplicated diagonally. Periods of darkness are shaded. For the first 6 days, animals were exposed to a 12:12 h light:dark (LD) cycle (dark from 19:00 to 07:00). On day 7, the LD cycle was advanced by 8 h (dark from 11:00 to 23:00) via a shortened light period of four hours. On day 17, the LD cycle was returned to the original lighting regime (dark 19:00 to 07:00) via a light period of 20 h. From day 30, animals were maintained in constant darkness.

Table 1.

Statistical analysis of the wheel running activity

| Transgenic

|

Wild-type

|

Statistic

|

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | SEM | Mean | SEM | F | P | |

| Wheel-running activity | 37,588 | 2,681 | 36,968 | 5,681 | 0.013 | 0.91 |

| Re-entrainment to phase advance, days | 3.86 | 0.21 | 5.40 | 0.57 | 9.03 | 0.007* |

| Re-entrainment to phase delay, days | 2.67 | 0.48 | 3.38 | 0.65 | 0.75 | 0.39 |

| Circadian period, h | 23.36 | 0.08 | 23.95 | 0.14 | 23.59 | <0.001* |

Data for the four quantified behavioral parameters tabulated according to group with mean, SEM, F, and P values as derived from the appropriate ANOVA. An asterisk indicates where the difference between the transgenic and wild-type mice was significant at the P < 0.05 level; in all cases, the degrees of freedom were 1 and 20.

Discussion

We have used a two-step genetic manipulation system to generate transgenic mice expressing the epitope-tagged human VPAC2R gene and the lacZ reporter gene from a dicistronic YAC construct. The human VPAC2R and lacZ transgenes were expressed in a pattern that closely resembles the published distribution of the VPAC2R (19, 24–26), with the highest levels of expression in the SCN. To our knowledge, there have been no other reports of the use of a dicistronic YAC construct, in which expression of a reporter gene is coupled to an epitope-tagged transgene, for the production of transgenic animals.

Overexpression of the human VPAC2R in transgenic mice resulted in an altered circadian phenotype, characterized by more rapid adaptation to an 8-h advance in the LD cycle and a significantly shorter circadian period in DD. Because the VPAC2R exhibits equal affinity for both VIP and PACAP, the effects of overexpression of the VPAC2R may reflect an enhancement of responsiveness to either or both of these neuropeptides. Both VIP (8, 9) and PACAP (27) have been shown to mimic the phase-advancing and -delaying effects of light pulses when administered in vivo during the subjective night. In vitro, the effects of PACAP appear to be dose-dependent: low doses of PACAP (10–100 pM) have been reported to reset the clock in a manner that mimics the effects of light, possibly via a glutamatergic mechanism (27, 28), whereas higher doses of PACAP (>10 nM) have been reported to be most effective during the subjective day, inducing phase shifts (15, 27) and stimulating the phosphorylation of the transcription factor Ca2+/cAMP response element-binding protein CREB (29). It seems possible that the effects of PACAP during the subjective day are mediated by the PAC1 receptor, because one study (15) showed VIP to be ≈1000-fold less potent than PACAP in this context. However, it is plausible that some of the actions of PACAP on the SCN are mediated by the VPAC2R.

The predominant intracellular signaling mechanism activated by the VPAC2R is the stimulation of adenylate cyclase and subsequent activation of protein kinase A. The VPAC2R might influence circadian behavior through the phosphorylation of CREB, which has been proposed to play a major role as a molecular mediator integrating various resetting cues that impinge on the circadian clock (29).

Outside the SCN, the lacZ reporter gene was expressed in a pattern similar to the published distribution of VPAC2R mRNA and binding sites. The expression of the lacZ reporter gene in cerebral arteries was unexpected, although consistent with reports of the presence of VIP binding sites (30–33) and vasorelaxant effects of VIP (30, 34) in cerebral arteries. Expression of the transgene was not detected in the thalamus, which represents one of the most abundant sites of expression of the endogenous VPAC2R in the rodent brain (24–26). It remains to be established whether there are species differences between rodents and man in the distribution of the VPAC2R within the central nervous system. Alternatively, it is possible that the 550-kb YAC HSC7E526 might lack regulatory elements necessary for thalamic expression.

The YAC vectors described in this study may find widespread application in studies of gene function and regulation in transgenic animals. The vector pYAM4, which was used to introduce a conditional centromere into the YAC, increasing the yield of DNA available for microinjection into fertilized eggs, has a number of advantages over existing YAC amplification vectors (35, 36). pYAM4 does not contain the herpes simplex virus thymidine kinase (TK) gene, which causes male infertility in transgenic animals (37). In addition, the homologous recombination efficiency with pYAM4 is much higher (13%) than with existing YAC amplification vectors, and pYAM4 contains a selectable marker (hygromycin B resistance) that facilitates the transfer of YAC DNA into cultured cell lines.

The availability of transgenic mice overexpressing the epitope-tagged VPAC2R gene and the lacZ reporter gene in an appropriate tissue-specific manner should facilitate the understanding of the role of the VPAC2R in a number of physiological processes, including the control of circadian rhythms, of cerebral blood flow (30, 34), and of glucose-stimulated insulin secretion in the pancreas (38). In addition, YAC transgenic animals expressing the human VPAC2R gene can be bred with VPAC2R null mice¶ to generate animals expressing the human VPAC2R exclusively, a model that may be valuable for assessing the application of VPAC2R agonists and antagonists to human subjects.

Acknowledgments

We thank Professors Nick Hastie, Richard Morris, and John Kelly for helpful criticism of the manuscript. The study was supported by the Medical Research Council, by the Wellcome Trust, and by the European Commission (BIO4980517).

Abbreviations

- YAC

yeast artificial chromosome

- HA

hemagglutinin

- IRES

internal ribosome entry site

- SCN

suprachiasmatic nuclei

- VIP

vasoactive intestinal peptide

- PACAP

pituitary adenylate cyclase-activating polypeptide

- X-Gal

5-bromo-4-chloro-3-indolyl-β-d-galactoside

- LD

light-dark

- DD

constant darkness

Footnotes

West, K. M., Shen, S., Sheward, W. J., Mackay, M. E. H., Kilanowski, F. M., Lutz, E. M., Dorin, J. R. & Harmar, A. J. (1998) Soc. Neurosci. Abstr. 24, 2049 (abstr.).

References

- 1.Mikkelsen J D, Fahrenkrug J. Brain Res. 1994;656:95–107. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(94)91370-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Loren I, Emson P C, Fahrenkrug J, Bjorklund A, Alumets J, Hakanson R, Sundler F. Neuroscience. 1979;4:1953–1976. doi: 10.1016/0306-4522(79)90068-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Tanaka M, Ichitani Y, Okamura H, Tanaka Y, Ibata Y. Brain Res Bull. 1993;31:637–640. doi: 10.1016/0361-9230(93)90134-w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ibata Y, Tanaka M, Ichitani Y, Takahashi Y, Okamura H. Neuroreport. 1993;4:128–130. doi: 10.1097/00001756-199302000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Shinohara K, Tominaga K, Isobe Y, Inouye S T. J Neurosci. 1993;13:793–800. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.13-02-00793.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Yang J, Cagampang F R, Nakayama Y, Inouye S I. Mol Brain Res. 1993;20:259–262. doi: 10.1016/0169-328x(93)90049-u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Albers H E, Stopa E G, Zoeller R T, Kauer J S, King J C, Fink J S, Mobtaker H, Wolfe H. Mol Brain Res. 1990;7:85–89. doi: 10.1016/0169-328x(90)90077-q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Piggins H D, Antle M C, Rusak B. J Neurosci. 1995;15:5612–5622. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.15-08-05612.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Albers H E, Liou S Y, Stopa E G, Zoeller R T. J Neurosci. 1991;11:846–851. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.11-03-00846.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gozes I, Lilling G, Glazer R, Ticher A, Ashkenazi I E, Davidson A, Rubinraut S, Fridkin M, Brenneman D E. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1995;273:161–167. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Scarbrough K, Harney J P, Rosewell K L, Wise P M. Am J Physiol. 1996;270:R283–R288. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.1996.270.1.R283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lucas R J, Cagampang F R, Loudon A S, Stirland J A, Coen C W. Neurosci Lett. 1998;249:147–150. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3940(98)00421-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Peters R V, Zoeller R T, Hennessey A C, Stopa E G, Anderson G, Albers H E. Brain Res. 1994;639:217–227. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(94)91733-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hannibal J, Moller M, Ottersen O P, Fahrenkrug J. J Comp Neurol. 2000;418:147–155. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hannibal J, Ding J M, Chen D, Fahrenkrug J, Larsen P J, Gillette M U, Mikkelsen J D. J Neurosci. 1997;17:2637–2644. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.17-07-02637.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fukuhara C, Suzuki N, Matsumoto Y, Nakayama Y, Aoki K, Tsujimoto G, Inouye S I, Masuo Y. Neurosci Lett. 1997;229:49–52. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3940(97)00415-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Harrington M E, Hoque S. Neuroreport. 1997;8:2677–2680. doi: 10.1097/00001756-199708180-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Harmar A J, Arimura A, Gozes I, Journot L, Laburthe M, Pisegna J R, Rawlings S R, Robberecht P, Said S I, Sreedharan S P, Wank S A, Waschek J A. Pharmacol Rev. 1998;50:265–270. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cagampang F R A, Sheward W J, Harmar A J, Piggins H D, Coen C W. Mol Brain Res. 1998;54:108–112. doi: 10.1016/s0169-328x(97)00327-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mackay M, Fantes J, Scherer S, Boyle S, West K, Tsui L C, Belloni E, Lutz E, Van Heyningen V, Harmar A J. Genomics. 1996;37:345–353. doi: 10.1006/geno.1996.0569. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Schedl A, Grimes B, Montoliu L. In: Yeast Artificial Chromosomes (YAC) Protocols. Markie D, editor. Vol. 54. Totowa, NJ: Humana; 1995. pp. 293–306. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Provencio I, Foster R G. Brain Res. 1995;694:183–190. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(95)00694-l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lutz E M, Shen S, Mackay M, West K M, Harmar A J. FEBS Lett. 1999;458:197–203. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(99)01135-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sheward W J, Lutz E M, Harmar A J. Neuroscience. 1995;67:409–418. doi: 10.1016/0306-4522(95)00048-n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Usdin T B, Bonner T I, Mezey E. Endocrinology. 1994;135:2662–2680. doi: 10.1210/endo.135.6.7988457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Vertongen P, Schiffmann S N, Gourlet P, Robberecht P. Peptides. 1997;18:1547–1554. doi: 10.1016/s0196-9781(97)00229-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Harrington M E, Hoque S, Hall A, Golombek D, Biello S. J Neurosci. 1999;19:6637–6642. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.19-15-06637.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Chen D, Buchanan G F, Ding J M, Hannibal J, Gillette M U. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1999;96:13468–13473. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.23.13468. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.von Gall C, Duffield G E, Hastings M H, Kopp M D, Dehghani F, Korf H W, Stehle J H. J Neurosci. 1998;18:10389–10397. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.18-24-10389.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Suzuki Y, McMaster D, Huang M, Lederis K, Rorstad O P. J Neurochem. 1985;45:890–899. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.1985.tb04077.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Poulin P, Suzuki Y, Lederis K, Rorstad O P. Brain Res. 1986;381:382–384. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(86)90094-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Martin J L, Feinstein D L, Yu N, Sorg O, Rossier C, Magistretti P J. Brain Res. 1992;587:1–12. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(92)91423-c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Amenta F, Cavalotti C, De Michele M, De Vincentis G, Rossodivita A, Rossodivita I. J Auton Pharmacol. 1991;11:285–293. doi: 10.1111/j.1474-8673.1991.tb00252.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Seki Y, Suzuki Y, Baskaya M K, Kano T, Saito K, Takayasu M, Shibuya M, Sugita K. Eur J Pharmacol. 1995;275:259–266. doi: 10.1016/0014-2999(95)00011-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Smith D R, Smyth A P, Moir D T. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1990;87:8242–8246. doi: 10.1073/pnas.87.21.8242. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Smith D R, Smyth A P, Strauss W M, Moir D T. Mamm Genome. 1993;4:141–147. doi: 10.1007/BF00352229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Al-Shawi R, Burke J, Jones C T, Simons J P, Bishop J O. Mol Cell Biol. 1988;8:4821–4828. doi: 10.1128/mcb.8.11.4821. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Straub S G, Sharp G W. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:1660–1668. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.3.1660. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]