Abstract

Background—Flufenamic acid, a fenamate, has been shown to alter markedly the membrane potential of small intestinal smooth muscle and increase intracellular calcium in single cells. Aims—To determine the effects of flufenamic acid on myoelectrical motor activity and gastrointestinal transit in the intact animal. Methods—Myoelectrical motor activity was recorded via seromuscular platinum electrodes sutured at regular intervals in the stomach and throughout the small intestine. Fasted and fed gastrointestinal transit was assessed using technetium-99m (99mTc) as the radioactive marker linked to 1 mm amberlite pellets or added to the meal. Results—Flufenamic acid (600 mg, intravenously) induced intense spike activity in the small intestine. The mean duration of irregular spike activity was 250 (7) minutes. Spike activity was more pronounced in the lower small intestine. Flufenamic acid also accelerated initial gastric emptying and markedly shortened transit time in the small intestine. In the fasted state the 50% transit time in the small intestine was 54 (8) minutes with infusion of flufenamic acid compared with 105 (10) minutes in the control group; in the fed state 99mTc first reached the colon at 220 (10) minutes compared with 270(12) minutes in the control group. Conclusions—Flufenamic acid had marked effects on both myoelectrical motor complex activity and small intestinal transit in the dog. The observed effects suggest that flufenamic acid may be of potential use as a prokinetic agent.

Keywords: prokinetic agents; transit studies; migrating motor complex

Full Text

The Full Text of this article is available as a PDF (229.2 KB).

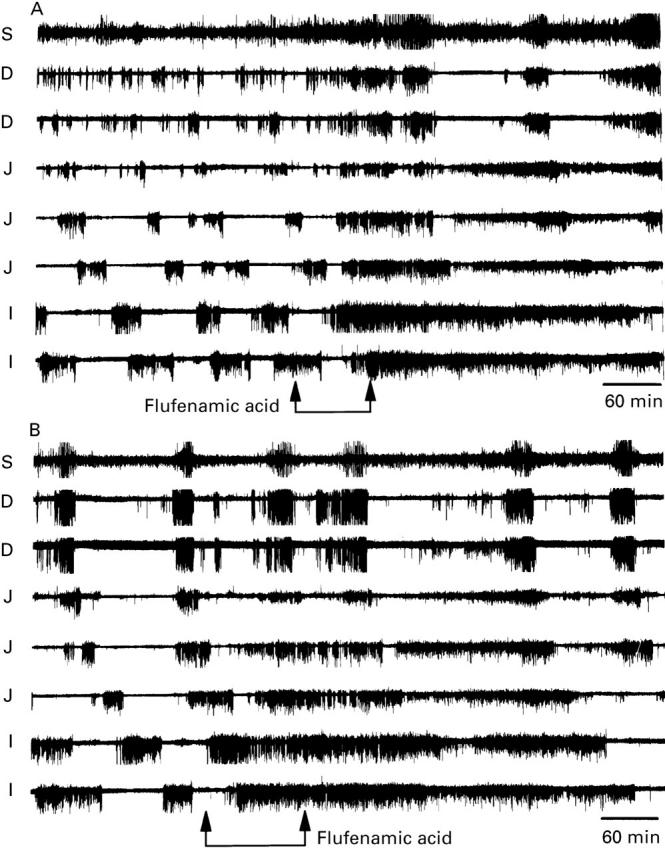

Figure 1 .

The effect of flufenamic acid ((A) 300 mg in 250 ml of normal Ringer's at 3 ml/min; (B) 600 mg in 500 ml of normal Ringer's at 4.4 ml/min) on the MMC recorded in separate experiments on the same dog. Data were recorded from one stomach (S) lead, two duodenal (D) leads, three jejunal (J) leads, and two ileal (I) leads. Twenty five minutes after the infusion was started, the normal MMC was replaced by intense spike activity. The effects of flufenamic acid were more noticeable in the distal leads where they appeared to last longer. The increase in spike activity lasted 5.5 hours in (A) and 7 hours in (B).

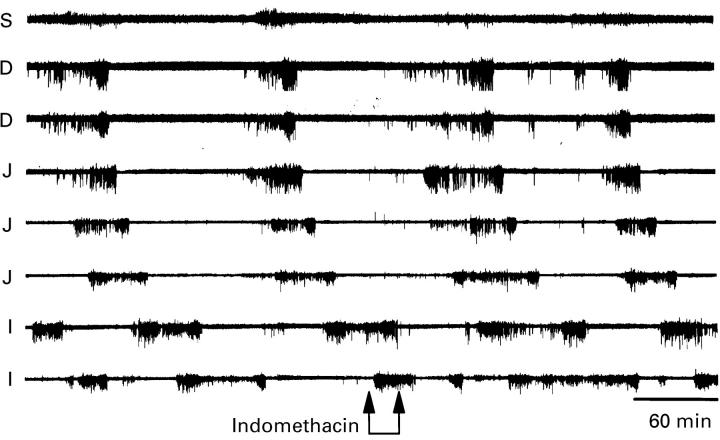

Figure 2 .

Lack of effect of indomethacin (250 mg, intravenously) on the MMC. Data were recorded from one stomach (S) lead, two duodenal (D) leads, three jejunal (J) leads, and two ileal (I) leads.

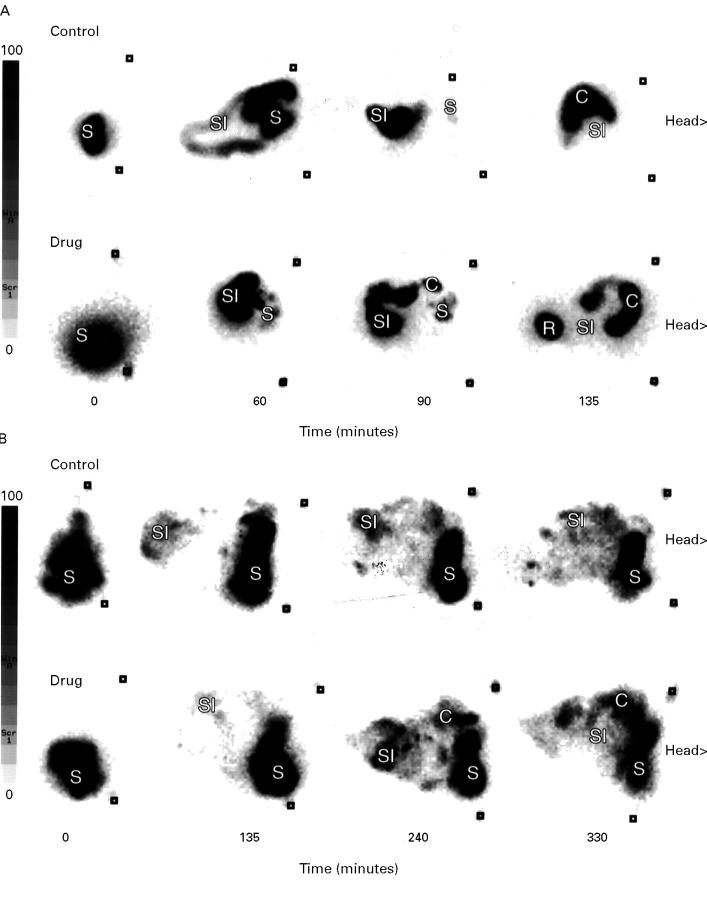

Figure 3 .

Representative examples of the effects of flufenamic acid (600 mg, intravenously) on transit time in the fasted (A) and fed (B) dog (S, stomach; SI, small intestine; C, colon; R, rectum).

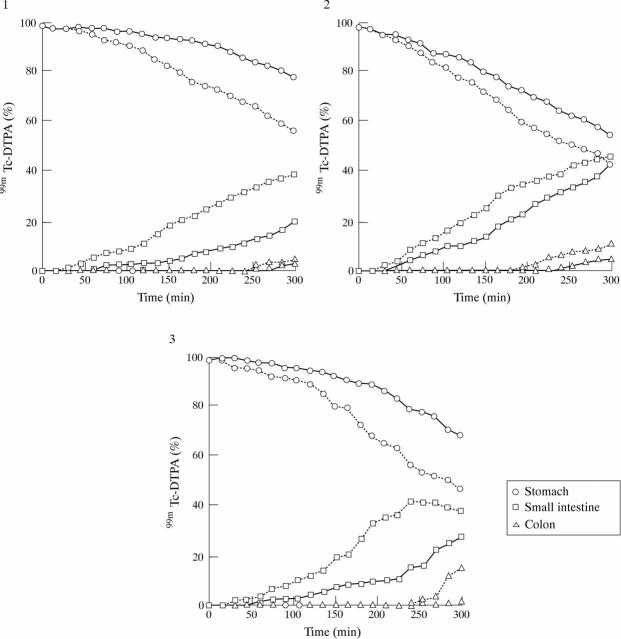

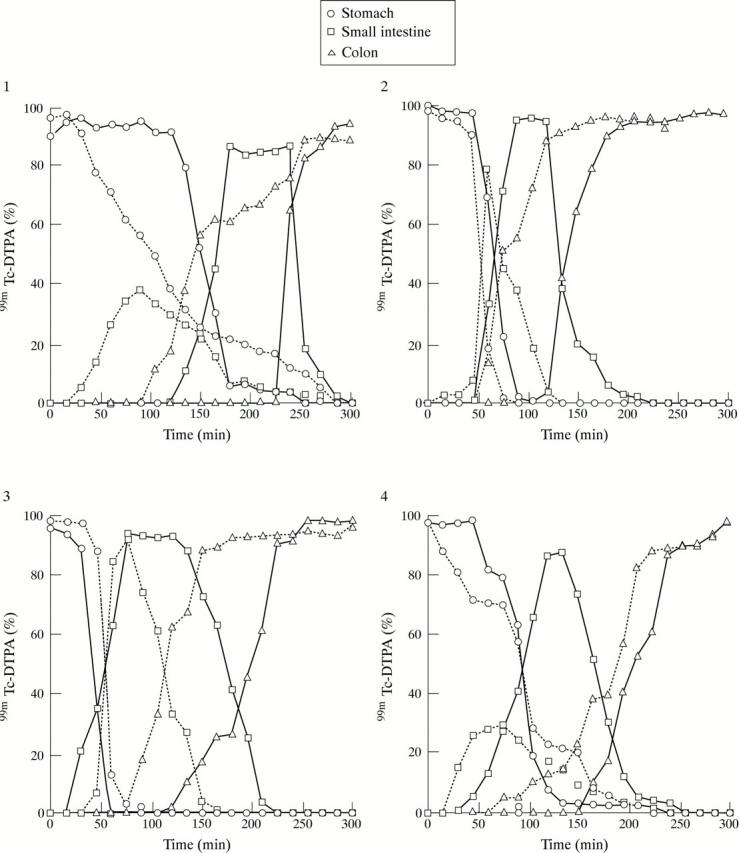

Figure 4 .

Plots of the 99mTc counts obtained for each of the four dogs in the fasted state (—, control; ...., drug).

Figure 5 .

Plots of the 99mTc counts obtained for each of the three dogs in the fed state (—, control; ...., drug).

Selected References

These references are in PubMed. This may not be the complete list of references from this article.

- Arai I., Hamasaka Y., Futaki N., Takahashi S., Yoshikawa K., Higuchi S., Otomo S. Effect of NS-398, a new nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory agent, on gastric ulceration and acid secretion in rats. Res Commun Chem Pathol Pharmacol. 1993 Sep;81(3):259–270. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bennett A., Hensby C. N., Sanger G. J., Stamford I. F. Metabolites of arachidonic acid formed by human gastrointestinal tissues and their actions on the muscle layers. Br J Pharmacol. 1981 Oct;74(2):435–444. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1981.tb09989.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Camilleri M., Zinsmeister A. R., Greydanus M. P., Brown M. L., Proano M. Towards a less costly but accurate test of gastric emptying and small bowel transit. Dig Dis Sci. 1991 May;36(5):609–615. doi: 10.1007/BF01297027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farrugia G., Camilleri M., Whitehead W. E. Therapeutic strategies for motility disorders. Medications, nutrition, biofeedback, and hypnotherapy. Gastroenterol Clin North Am. 1996 Mar;25(1):225–246. doi: 10.1016/s0889-8553(05)70373-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farrugia G., Rae J. L., Sarr M. G., Szurszewski J. H. Potassium current in circular smooth muscle of human jejunum activated by fenamates. Am J Physiol. 1993 Nov;265(5 Pt 1):G873–G879. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.1993.265.5.G873. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farrugia G., Rae J. L., Szurszewski J. H. Characterization of an outward potassium current in canine jejunal circular smooth muscle and its activation by fenamates. J Physiol. 1993 Aug;468:297–310. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1993.sp019772. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gögelein H., Dahlem D., Englert H. C., Lang H. J. Flufenamic acid, mefenamic acid and niflumic acid inhibit single nonselective cation channels in the rat exocrine pancreas. FEBS Lett. 1990 Jul 30;268(1):79–82. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(90)80977-q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gögelein H., Pfannmüller B. The nonselective cation channel in the basolateral membrane of rat exocrine pancreas. Inhibition by 3',5-dichlorodiphenylamine-2-carboxylic acid (DCDPC) and activation by stilbene disulfonates. Pflugers Arch. 1989 Jan;413(3):287–298. doi: 10.1007/BF00583543. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knauf P. A., Mann N. A. Use of niflumic acid to determine the nature of the asymmetry of the human erythrocyte anion exchange system. J Gen Physiol. 1984 May;83(5):703–725. doi: 10.1085/jgp.83.5.703. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nguyen A., Camilleri M., Kost L. J., Metzger A., Sarr M. G., Hanson R. B., Fett S. L., Zinsmeister A. R. SDZ HTF 919 stimulates canine colonic motility and transit in vivo. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1997 Mar;280(3):1270–1276. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nitecki S., Karmeli R., Harty G. J., Kamei C., Yaksh T. L., Szurszewski J. H. Long-term perfusion of the cerebroventricular system of dogs without leakage to the peripheral circulation. Am J Physiol. 1994 Nov;267(5 Pt 2):R1309–R1319. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.1994.267.5.R1309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ottolia M., Toro L. Potentiation of large conductance KCa channels by niflumic, flufenamic, and mefenamic acids. Biophys J. 1994 Dec;67(6):2272–2279. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(94)80712-X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rae J. L., Farrugia G. Whole-cell potassium current in rabbit corneal epithelium activated by fenamates. J Membr Biol. 1992 Jul;129(1):81–97. doi: 10.1007/BF00232057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanger G. J., Bennett A. Regional differences in the responses to prostanoids of circular muscle from guinea-pig isolated intestine. J Pharm Pharmacol. 1980 Oct;32(10):705–708. doi: 10.1111/j.2042-7158.1980.tb13043.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Terada H., Muraoka S., Fujita T. Structure-activity relationships of fenamic acids. J Med Chem. 1974 Mar;17(3):330–334. doi: 10.1021/jm00249a016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- White M. M., Aylwin M. Niflumic and flufenamic acids are potent reversible blockers of Ca2(+)-activated Cl- channels in Xenopus oocytes. Mol Pharmacol. 1990 May;37(5):720–724. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- von der Ohe M. R., Camilleri M. Measurement of small bowel and colonic transit: indications and methods. Mayo Clin Proc. 1992 Dec;67(12):1169–1179. doi: 10.1016/s0025-6196(12)61147-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]