Abstract

Background—Reactive oxygen species contribute to tissue injury in inflammatory bowel disease (IBD). The tripeptide glutathione (GSH) is the most important intracellular antioxidant. Aims—To investigate constituent amino acid plasma levels and the GSH redox status in different compartments in IBD with emphasis on intestinal GSH synthesis in Crohn's disease. Methods—Precursor amino acid levels were analysed in plasma and intestinal mucosa. Reduced (rGSH) and oxidised glutathione (GSSG) were determined enzymatically in peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMC), red blood cells (RBC), muscle, and in non-inflamed and inflamed ileum mucosa. Mucosal enzyme activity of γ-glutamylcysteine synthetase (γGCS) and γ-glutamyl transferase (γGT) was analysed. Blood of healthy subjects and normal mucosa from a bowel segment resected for tumour growth were used as controls. Results—Abnormally low plasma cysteine and cystine levels were associated with inflammation in IBD (p<10-4). Decreased rGSH levels were demonstrated in non-inflamed mucosa (p<0.01) and inflamed mucosa (p=10-6) in patients with IBD, while GSSG increased with inflammation (p=0.007) compared with controls. Enzyme activity of γGCS was reduced in non-inflamed mucosa (p<0.01) and, along with γGT, in inflamed mucosa (p<10-4). The GSH content was unchanged in PBMC, RBC, and muscle. Conclusions—Decreased activity of key enzymes involved in GSH synthesis accompanied by a decreased availability of cyst(e)ine for GSH synthesis contribute to mucosal GSH deficiency in IBD. As the impaired mucosal antioxidative capacity may further promote oxidative damage, GSH deficiency might be a target for therapeutic intervention in IBD.

Keywords: Crohn's disease; ulcerative colitis; glutathione; amino acids; γ-glutamylcysteine synthetase; mucosa

Full Text

The Full Text of this article is available as a PDF (167.2 KB).

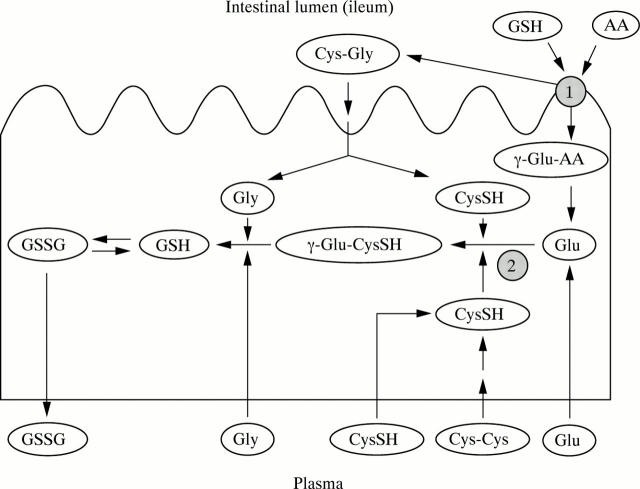

Figure 1 .

Simplified diagram of mucosal glutathione synthesis in the ileum. GSH, glutathione; GSSG, glutathione disulphide; Gly, glycine; CysSH, cysteine; Cys-Cys, cystine; Glu, glutamate; AA, amino acid; γ-Glu-AA, γ-glutamyl-amino acid; γ-Glu-CysSH, γ-glutamylcysteine; Cys-Gly, cysteinylglycine. (1) Site of action of γ-glutamyl transferase; (2) site of action of γ-glutamylcysteine synthetase. For further information see introduction.

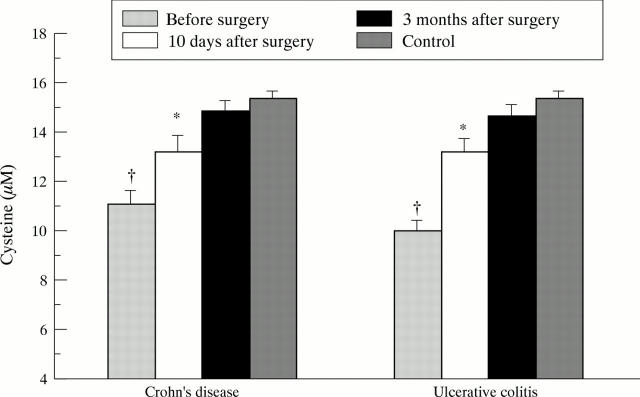

Figure 2 .

Fasting plasma cysteine levels in patients with Crohn's disease (n=33) and ulcerative colitis (n=33) before surgery and 10 days and three months after complete resection of inflamed bowel. Bars represent mean (SE). Data were statistically analysed by the Student's t test for unpaired samples including a Bonferroni's correction. *p<0.008, †p<10-4 versus controls (n=65).

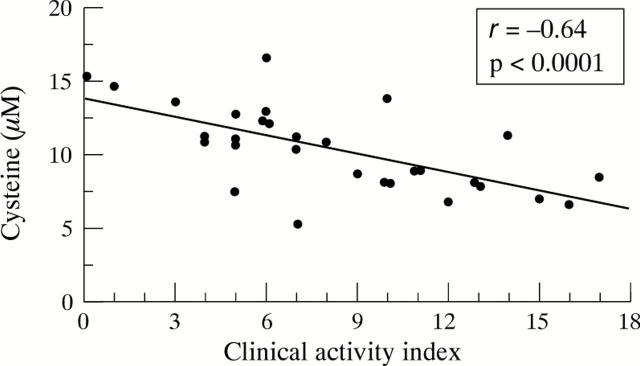

Figure 3 .

Linear regression analysis of preoperative plasma cysteine levels plotted against the individual clinical activity index according to Rachmilewitz in patients with ulcerative colitis.

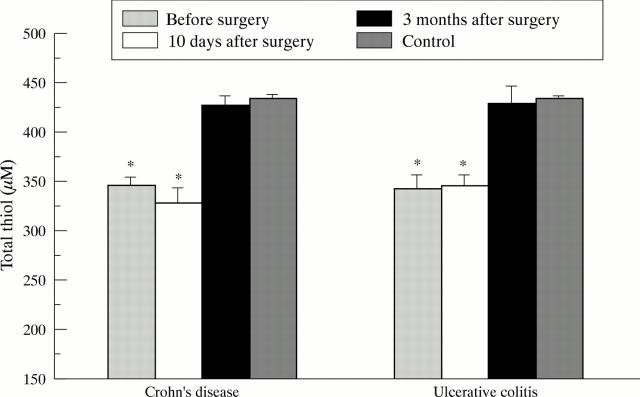

Figure 4 .

Total thiol levels in non-deproteinised plasma in patients with Crohn's disease (n=33) and ulcerative colitis (n=33) before surgery and 10 days and three months after complete resection of inflamed bowel. Values represent means (SE) and were statistically analysed by the Student's t test for unpaired samples. According to Bonferroni's correction the level of significance was set at p<0.008. *p<10-4 versus controls (n=65).

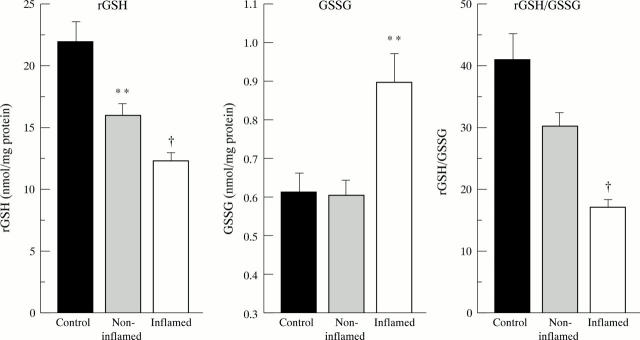

Figure 5 .

Pro-oxidant glutathione status in the mucosa of freshly resected ileum in patients with Crohn's disease. Reduced glutathione (rGSH) is decreased in inflamed (n=26) as well as non-inflamed (n=21) mucosa in Crohn's disease. Oxidised glutathione (GSSG) is increased in areas of inflammation so that the redox status of glutathione, as defined by the ratio rGSH/GSSG, is heavily decreased in inflamed mucosa. Bars represent mean (SE). Statistical analysis was performed by the Student's t test including a Bonferroni's correction. **p<0.01, †p<10-4 versus controls (n=21).

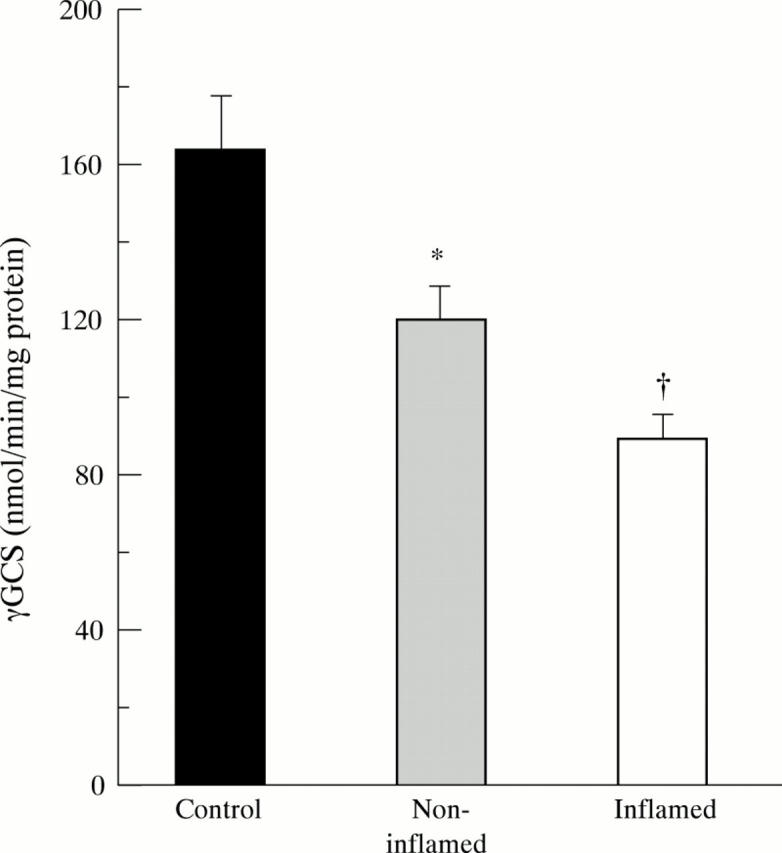

Figure 6 .

Decreased mucosal enzyme activity of γ-glutamylcysteine synthetase (γGCS) in inflamed (n=26) and non-inflamed (n=21) ileum of patients with Crohn's disease. Bars represent mean (SE). Statistical analysis was performed by the Student's t test for unpaired samples including a Bonferroni's correction. *p<0.025, †p<10-4 versus controls (n=21).

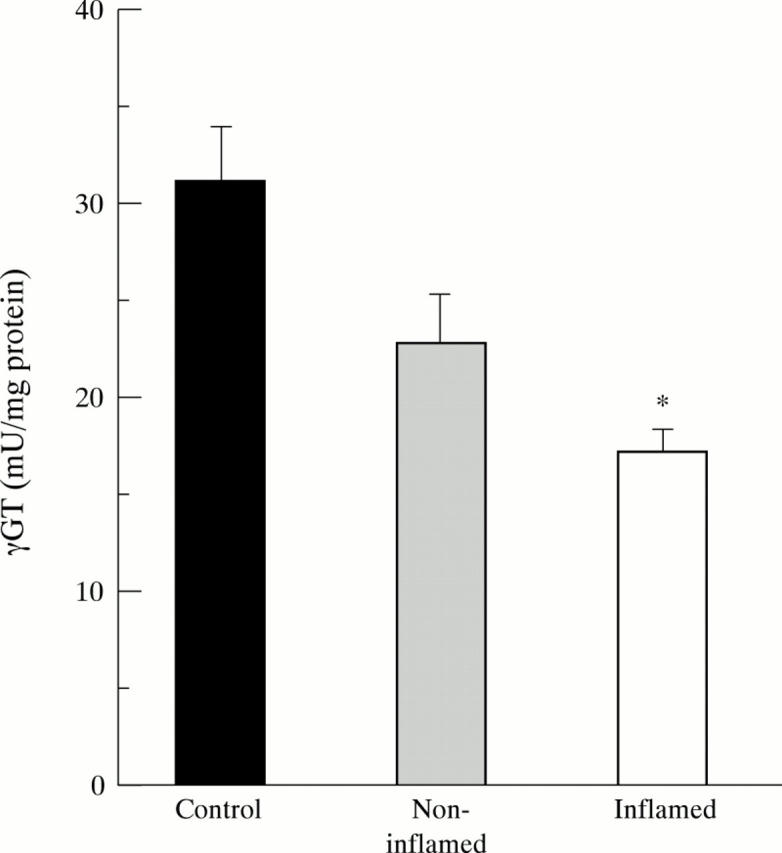

Figure 7 .

Decreased mucosal enzyme activity of γ-glutamyl transferase (γGT) in inflamed (n=26) and non-inflamed (n=21) ileum of patients with Crohn's disease. Bars represent mean (SE). Statistical analysis was performed by the Student's t test for unpaired samples. According to Bonferroni's correction the level of significance was set at p<0.025. *p<10-4 versus controls (n=21).

Selected References

These references are in PubMed. This may not be the complete list of references from this article.

- Ahnfelt-Rønne I., Nielsen O. H., Christensen A., Langholz E., Binder V., Riis P. Clinical evidence supporting the radical scavenger mechanism of 5-aminosalicylic acid. Gastroenterology. 1990 May;98(5 Pt 1):1162–1169. doi: 10.1016/0016-5085(90)90329-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ahnfelt-Rønne I., Nielsen O. H. The antiinflammatory moiety of sulfasalazine, 5-aminosalicylic acid, is a radical scavenger. Agents Actions. 1987 Jun;21(1-2):191–194. doi: 10.1007/BF01974941. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Babbs C. F. Oxygen radicals in ulcerative colitis. Free Radic Biol Med. 1992;13(2):169–181. doi: 10.1016/0891-5849(92)90079-v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bannai S. Exchange of cystine and glutamate across plasma membrane of human fibroblasts. J Biol Chem. 1986 Feb 15;261(5):2256–2263. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bannai S., Kitamura E. Transport interaction of L-cystine and L-glutamate in human diploid fibroblasts in culture. J Biol Chem. 1980 Mar 25;255(6):2372–2376. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Best W. R., Becktel J. M., Singleton J. W., Kern F., Jr Development of a Crohn's disease activity index. National Cooperative Crohn's Disease Study. Gastroenterology. 1976 Mar;70(3):439–444. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bradford M. M. A rapid and sensitive method for the quantitation of microgram quantities of protein utilizing the principle of protein-dye binding. Anal Biochem. 1976 May 7;72:248–254. doi: 10.1006/abio.1976.9999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cornell J. S., Meister A. Glutathione and gamma-glutamyl cycle enzymes in crypt and villus tip cells of rat jejunal mucosa. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1976 Feb;73(2):420–422. doi: 10.1073/pnas.73.2.420. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dallegri F., Ottonello L., Ballestrero A., Bogliolo F., Ferrando F., Patrone F. Cytoprotection against neutrophil derived hypochlorous acid: a potential mechanism for the therapeutic action of 5-aminosalicylic acid in ulcerative colitis. Gut. 1990 Feb;31(2):184–186. doi: 10.1136/gut.31.2.184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeLucia A. J., Mustafa M. G., Hussain M. Z., Cross C. E. Ozone interaction with rodent lung. III. Oxidation of reduced glutathione and formation of mixed disulfides between protein and nonprotein sulfhydryls. J Clin Invest. 1975 Apr;55(4):794–802. doi: 10.1172/JCI107990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eck H. P., Drings P., Dröge W. Plasma glutamate levels, lymphocyte reactivity and death rate in patients with bronchial carcinoma. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol. 1989;115(6):571–574. doi: 10.1007/BF00391360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eck H. P., Dröge W. Influence of the extracellular glutamate concentration on the intracellular cyst(e)ine concentration in macrophages and on the capacity to release cysteine. Biol Chem Hoppe Seyler. 1989 Feb;370(2):109–113. doi: 10.1515/bchm3.1989.370.1.109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eck H. P., Gmünder H., Hartmann M., Petzoldt D., Daniel V., Dröge W. Low concentrations of acid-soluble thiol (cysteine) in the blood plasma of HIV-1-infected patients. Biol Chem Hoppe Seyler. 1989 Feb;370(2):101–108. doi: 10.1515/bchm3.1989.370.1.101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Emerit J., Pelletier S., Likforman J., Pasquier C., Thuillier A. Phase II trial of copper zinc superoxide dismutase (CuZn SOD) in the treatment of Crohn's disease. Free Radic Res Commun. 1991;12-13 Pt 2:563–569. doi: 10.3109/10715769109145831. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gmünder H., Eck H. P., Benninghoff B., Roth S., Dröge W. Macrophages regulate intracellular glutathione levels of lymphocytes. Evidence for an immunoregulatory role of cysteine. Cell Immunol. 1990 Aug;129(1):32–46. doi: 10.1016/0008-8749(90)90184-s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Griffith O. W. Determination of glutathione and glutathione disulfide using glutathione reductase and 2-vinylpyridine. Anal Biochem. 1980 Jul 15;106(1):207–212. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(80)90139-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grisham M. B., Granger D. N. Neutrophil-mediated mucosal injury. Role of reactive oxygen metabolites. Dig Dis Sci. 1988 Mar;33(3 Suppl):6S–15S. doi: 10.1007/BF01538126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grisham M. B., MacDermott R. P., Deitch E. A. Oxidant defense mechanisms in the human colon. Inflammation. 1990 Dec;14(6):669–680. doi: 10.1007/BF00916370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grisham M. B. Oxidants and free radicals in inflammatory bowel disease. Lancet. 1994 Sep 24;344(8926):859–861. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(94)92831-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grisham M. B., Volkmer C., Tso P., Yamada T. Metabolism of trinitrobenzene sulfonic acid by the rat colon produces reactive oxygen species. Gastroenterology. 1991 Aug;101(2):540–547. doi: 10.1016/0016-5085(91)90036-k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gross V., Arndt H., Andus T., Palitzsch K. D., Schölmerich J. Free radicals in inflammatory bowel diseases pathophysiology and therapeutic implications. Hepatogastroenterology. 1994 Aug;41(4):320–327. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hack V., Gross A., Kinscherf R., Bockstette M., Fiers W., Berke G., Dröge W. Abnormal glutathione and sulfate levels after interleukin 6 treatment and in tumor-induced cachexia. FASEB J. 1996 Aug;10(10):1219–1226. doi: 10.1096/fasebj.10.10.8751725. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hack V., Schmid D., Breitkreutz R., Stahl-Henning C., Drings P., Kinscherf R., Taut F., Holm E., Dröge W. Cystine levels, cystine flux, and protein catabolism in cancer cachexia, HIV/SIV infection, and senescence. FASEB J. 1997 Jan;11(1):84–92. doi: 10.1096/fasebj.11.1.9034170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hagen T. M., Jones D. P. Transepithelial transport of glutathione in vascularly perfused small intestine of rat. Am J Physiol. 1987 May;252(5 Pt 1):G607–G613. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.1987.252.5.G607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hagen T. M., Wierzbicka G. T., Bowman B. B., Aw T. Y., Jones D. P. Fate of dietary glutathione: disposition in the gastrointestinal tract. Am J Physiol. 1990 Oct;259(4 Pt 1):G530–G535. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.1990.259.4.G530. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hagen T. M., Wierzbicka G. T., Sillau A. H., Bowman B. B., Jones D. P. Bioavailability of dietary glutathione: effect on plasma concentration. Am J Physiol. 1990 Oct;259(4 Pt 1):G524–G529. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.1990.259.4.G524. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iantomasi T., Marraccini P., Favilli F., Vincenzini M. T., Ferretti P., Tonelli F. Glutathione metabolism in Crohn's disease. Biochem Med Metab Biol. 1994 Dec;53(2):87–91. doi: 10.1006/bmmb.1994.1062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ishii T., Sugita Y., Bannai S. Regulation of glutathione levels in mouse spleen lymphocytes by transport of cysteine. J Cell Physiol. 1987 Nov;133(2):330–336. doi: 10.1002/jcp.1041330217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keshavarzian A., Sedghi S., Kanofsky J., List T., Robinson C., Ibrahim C., Winship D. Excessive production of reactive oxygen metabolites by inflamed colon: analysis by chemiluminescence probe. Gastroenterology. 1992 Jul;103(1):177–185. doi: 10.1016/0016-5085(92)91111-g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LOWRY O. H., ROSEBROUGH N. J., FARR A. L., RANDALL R. J. Protein measurement with the Folin phenol reagent. J Biol Chem. 1951 Nov;193(1):265–275. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lih-Brody L., Powell S. R., Collier K. P., Reddy G. M., Cerchia R., Kahn E., Weissman G. S., Katz S., Floyd R. A., McKinley M. J. Increased oxidative stress and decreased antioxidant defenses in mucosa of inflammatory bowel disease. Dig Dis Sci. 1996 Oct;41(10):2078–2086. doi: 10.1007/BF02093613. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mahida Y. R., Wu K. C., Jewell D. P. Respiratory burst activity of intestinal macrophages in normal and inflammatory bowel disease. Gut. 1989 Oct;30(10):1362–1370. doi: 10.1136/gut.30.10.1362. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meister A., Anderson M. E. Glutathione. Annu Rev Biochem. 1983;52:711–760. doi: 10.1146/annurev.bi.52.070183.003431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meister A. Selective modification of glutathione metabolism. Science. 1983 Apr 29;220(4596):472–477. doi: 10.1126/science.6836290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Millar A. D., Rampton D. S., Chander C. L., Claxson A. W., Blades S., Coumbe A., Panetta J., Morris C. J., Blake D. R. Evaluating the antioxidant potential of new treatments for inflammatory bowel disease using a rat model of colitis. Gut. 1996 Sep;39(3):407–415. doi: 10.1136/gut.39.3.407. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mårtensson J., Jain A., Meister A. Glutathione is required for intestinal function. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1990 Mar;87(5):1715–1719. doi: 10.1073/pnas.87.5.1715. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Niwa Y., Somiya K., Michelson A. M., Puget K. Effect of liposomal-encapsulated superoxide dismutase on active oxygen-related human disorders. A preliminary study. Free Radic Res Commun. 1985;1(2):137–153. doi: 10.3109/10715768509056547. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peters W. H., Roelofs H. M., Nagengast F. M., van Tongeren J. H. Human intestinal glutathione S-transferases. Biochem J. 1989 Jan 15;257(2):471–476. doi: 10.1042/bj2570471. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rachmilewitz D. Coated mesalazine (5-aminosalicylic acid) versus sulphasalazine in the treatment of active ulcerative colitis: a randomised trial. BMJ. 1989 Jan 14;298(6666):82–86. doi: 10.1136/bmj.298.6666.82. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richman P. G., Meister A. Regulation of gamma-glutamyl-cysteine synthetase by nonallosteric feedback inhibition by glutathione. J Biol Chem. 1975 Feb 25;250(4):1422–1426. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seelig G. F., Meister A. Glutathione biosynthesis; gamma-glutamylcysteine synthetase from rat kidney. Methods Enzymol. 1985;113:379–390. doi: 10.1016/s0076-6879(85)13050-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siebenlist U., Franzoso G., Brown K. Structure, regulation and function of NF-kappa B. Annu Rev Cell Biol. 1994;10:405–455. doi: 10.1146/annurev.cb.10.110194.002201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simmonds N. J., Allen R. E., Stevens T. R., Van Someren R. N., Blake D. R., Rampton D. S. Chemiluminescence assay of mucosal reactive oxygen metabolites in inflammatory bowel disease. Gastroenterology. 1992 Jul;103(1):186–196. doi: 10.1016/0016-5085(92)91112-h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tamai H., Kachur J. F., Grisham M. B., Gaginella T. S. Scavenging effect of 5-aminosalicylic acid on neutrophil-derived oxidants. Possible contribution to the mechanism of action in inflammatory bowel disease. 1991 Mar 15-Apr 1Biochem Pharmacol. 41(6-7):1001–1006. doi: 10.1016/0006-2952(91)90207-l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tamai H., Levin S., Gaginella T. S. Induction of colitis in rats by 2-2'-azobis(2-amidinopropane) dihydrochloride. Inflammation. 1992 Feb;16(1):69–81. doi: 10.1007/BF00917516. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vincenzini M. T., Favilli F., Iantomasi T. Intestinal uptake and transmembrane transport systems of intact GSH; characteristics and possible biological role. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1992 Mar 26;1113(1):13–23. doi: 10.1016/0304-4157(92)90032-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weiss S. J. Tissue destruction by neutrophils. N Engl J Med. 1989 Feb 9;320(6):365–376. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198902093200606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams J. G., Hallett M. B. The reaction of 5-amino-salicylic acid with hypochlorite. Implications for its mode of action in inflammatory bowel disease. Biochem Pharmacol. 1989 Jan 1;38(1):149–154. doi: 10.1016/0006-2952(89)90161-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams J. G., Hughes L. E., Hallett M. B. Toxic oxygen metabolite production by circulating phagocytic cells in inflammatory bowel disease. Gut. 1990 Feb;31(2):187–193. doi: 10.1136/gut.31.2.187. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams J. G. Phagocytes, toxic oxygen metabolites and inflammatory bowel disease: implications for treatment. Ann R Coll Surg Engl. 1990 Jul;72(4):253–262. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van der Vliet A., Bast A. Role of reactive oxygen species in intestinal diseases. Free Radic Biol Med. 1992;12(6):499–513. doi: 10.1016/0891-5849(92)90103-n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]